Post amended since first publication

Introduction

International humanitarian law (IHL), also known as the law of war, is a set of rules that aim to limit the effects of armed conflict for humanitarian reasons. It protects people who are not or no longer participating in hostilities and restricts the means and methods of warfare. IHL is about protecting people from the worst wars that rage today in Ukraine, Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and many other countries. The Geneva Conventions of 1949 are among the most universally ratified international treaties. Moreover, the 1864 Geneva Convention is one of the first, if not the first, treaty of public international law initiated by civil society (the five founders of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)).

As guardian and promoter of IHL, the ICRC has played a unique role in the history of this body of law. Being at the origin of the Geneva Conventions, it has contributed to the inception, development, and diffusion of IHL for over 160 years. The ICRC has also a long history of operational presence in countries affected by armed conflict. Its role has been acknowledged in the current 1949 Geneva Conventions, some of their provisions mentioning the organization and obliging States to allow and facilitate its relief work. Therefore, thanks to its dual mandate – law and action – the ICRC combines thought and action with IHL.

Using the ICRC’s archives and library collections as an example, this post aims to better understand the role of archives in fostering understanding and practice of IHL by answering several fundamental questions: What are the archival sources of IHL? Who are those consulting these sources? For what purpose? What do they produce? How was IHL developed and created? Why does it matter?

What are the archival sources on IHL?

IHL historical materials preserved at the ICRC go far beyond purely legal or scholarly documents. They also show the concrete and practical implementation of the law on the ground. They include the IHL treaties (copies of them, the original documents are preserved by the states depositories of the treaties), minutes and other papers produced during diplomatic conferences; circulars; internal reporting on operational activities; reports submitted to parties to conflicts; internal exchanges such as emails; correspondence with states, parties to the conflict, academics, civil society, and others; minutes of meetings with internal and external stakeholders; legal analysis and interpretation; minutes of expert workshops; dissemination material; public communication; archives and copies of the International Review of the Red Cross; ICRC publications; academic publications; military manuals; pictures, films/videos, and sound recordings; etc.

These sources illustrate the balance between thought and action that has accompanied the history of the ICRC and the development of IHL over the past 160 years.

Diverse audiences and multiple uses of the sources

ICRC archives have been open to the public since 1996. According to the ICRC’s rules of access, the public can access the archives until 1975. More recent documents such as publications, conference reports, press releases, and audiovisual archives are available at the ICRC library and/or online. Classified archives are only open to ICRC staff upon request.

The users of these rich resources have different objectives and interests when they consult them. One could identify the primary external audiences and some reasons why they use these resources.

Historians and other researchers analyzing our resources for historical research constitute a significant category of users. They come to the archives and the library to gather information ahead of publishing books, articles and other scholarly works. By using these historical sources, historians show that IHL was developed in specific historical contexts by particular people. They also show that it can adapt to the evolving nature of warfare. The history of IHL is an active field of research.

Many lawyers, judges, professors, and educators benefit from the historical and legal sources for the legal analysis and diffusion of IHL, as well as its teaching. In addition to lawyers and representatives from the judiciary, policymakers, diplomats, humanitarian practitioners, and other representatives from states and armed forces use them to establish their legal views and policy positions. Diplomatic officials have used the materials found in the ICRC archives and library to inform their statements before the UN General Assembly or other multilateral fora.

Last but not least, people affected by former or current conflicts, other humanitarian practitioners, members of NGOs and associations of victims, also find in the historical sources arguments for their advocacy and document their rights under IHL and violations of them.

Thus, the ICRC’s archival resources are valuable and relevant for many users and purposes. They contribute to a better understanding and respect for IHL and the humanitarian principles by providing context for the negotiation and adoption of the norms or by demonstrating how IHL has been interpreted in the past.

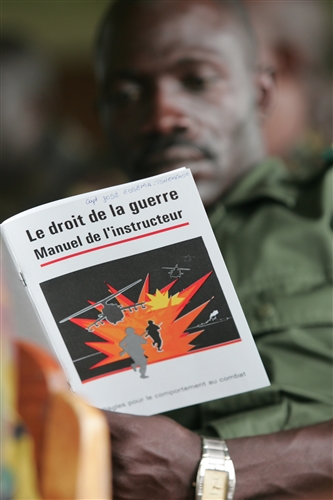

Kinshasa. Dissemination on international humanitarian law to officers of the Congolese army. ©ICRC/CRUPPE, MARIZILDA, 01/11/2004, V-P-CD-E-00272

ICRC colleagues constitute a significant audience of the archives and library. ICRC staff use our historical sources for various reasons related to their work in different contexts and situations. For example, they use archives for business continuity, to know what the ICRC did and said about the law in former and current armed conflicts. They use them for internal analysis to identify violations of IHL and patterns of conflict.

They also use them for legal reasons, to qualify a conflict, and to strengthen legal dialogue with stakeholders. The interpretation and application of IHL, including essential projects such as the Commentaries of the Geneva Conventions and additional protocols, require extensive analysis of past humanitarian and legal actions.

Our communication colleagues regularly use the ICRC’s audiovisual archives to illustrate their contributions and efforts to promote IHL.

Eventually, the ICRC operations and governance use these resources for decision-making to guide the organization’s actions and strategies, including in relation to the law.

In other words, these historical sources have a practical utility for the work of the ICRC today. They help to fulfill its mandate and to protect and assist the victims of armed conflict and other situations of violence.

How is IHL created and developed: the IHL “circle of life”[1]

Historical sources are essential to understand how this branch of law came into being, how it developed over time, and how it has evolved in response to new challenges. They show the stages and processes shaping humanitarian norms and principles.

First, witnesses of the consequences of warfare and humanitarian problems on the ground share accounts of their experience and propose concrete legal measures. The proposals trigger numerous debates and reflections among experts. Ultimately, the discussions may lead to the drafting of a new treaty and a diplomatic conference resulting in a new treaty and its signature and ratification by states.

For instance, when he arrived in Solferino, Henry Dunant witnessed the disastrous humanitarian consequences of the battle there the same day. His experience triggered the writing of a book and the proposal of what would become the Red Cross Movement and the first Geneva Convention.

Between 6 and 8 million prisoners of war were interned during the First World War. ICRC delegates visited internment camps and could notice the lack of regulations related to their fate. The ICRC published numerous articles in its Review[2] during and after the war, generating debates and, ultimately, the Geneva Convention of 1929. It then promoted the ratification, implementation, and respect of the new treaty.

The use of chemical weapons during the First World War also constituted an emblematic example of the consequences of industrialized warfare. Other articles in the Review and engaged dialogue with experts led to regulating these weapons in the 1925 Geneva Protocol[3]. A similar observation could be made about the consequences of air bombing during the thirties and forties[4].

The protection of civilians in war endeavored a longer journey. Already during the First World War, the ICRC slowly started to include the fate of civilians into its scope of action. This conflict, its aftermath, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, developed this interest and highlighted the lack of a legal framework protecting this category of people affected by armed conflict. Over more than a decade, these experiences and reflection expanded and led to the first version of a document integrating this protection, the famous “Tokyo draft” on the Condition and Protection of Civilians of enemy nationality who are on territory belonging to or occupied by a belligerent in 1934. The diplomatic conference that should have happened in 1940 was cancelled because of the Second World War. Following the conflict, and by considering the disastrous experiences of this conflict and others such as the Spanish Civil War, the drafting of a Convention protecting civilians resumed. Following expert meetings in Stockholm, the diplomatic conference of 1949 gave birth to the 4th Geneva Convention.

Since then, the ICRC has continuously promoted the diffusion and the respect of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. It has debated its interpretation, application with parties to conflicts for decades. It even published detailed commentaries on the conventions under the lead of Jean Pictet and the ICRC’s legal division is currently working on updated commentaries.

IHL historical sources do not stop with the adoption of treaties. They also document their national implementation by states and its diffusion among different actors such as armed forces, non-state armed groups, different levels of authorities, or civil society. They highlight the debate on the interpretation and application of treaties and its relevance for current and future situations. Finally, they contain an analysis of its application, respect, or violation in the field.

In other words, archival resources make it possible to understand the history and the present of humanitarian law. They help us to appreciate its complexity and its dynamic.

Conclusion

Eventually, why does it matter so much? Why are these archival sources important for people affected by armed conflict and for the ICRC itself to fulfill its mandate?

Our historical collections constitute prominent sources to understand and showcase when IHL was respected and when it was violated. More importantly, their analysis shows the benefits of respecting IHL as well as the humanitarian consequences when the law is violated.

However, one should not conclude from those sources that IHL serves to legitimate war by making it more acceptable. They instead highlight the importance of respecting the law to mitigate the consequences of warfare and the high human, social, economic, and environmental costs that arise when IHL is violated. In other words, they show that IHL makes a difference on the ground and that this difference matters for those affected by armed conflict.

Furthermore, the historical sources preserved at the ICRC also help the organization to learn from its past and adapt its work to old and new challenges. They help us continue the diffusion and promotion of the law. They bring perspectives to the current practice of this body of law.

Last but not least, the historical sources of IHL help us remember paying tribute to those who benefited from these treaties and those who were victims of their violation.

One hundred sixty years after its inception, international humanitarian law is still relevant and necessary. It deserves to be better known and acknowledged. As said in the introduction, the first Geneva Convention of 1864 was maybe the first public international treaty initiated by civil society. This trend has continued. Over the past decades, civil society has also contributed to recent IHL treaties, such as the Ottawa Convention on anti-personnel mines or the recent treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. The ICRC used its operational experience in the field and legal expertise in each step leading to the inception and adoption of these treaties.

Finally, the archival sources also recall to everyone the protection under IHL of people affected by armed conflict and the duties and responsibilities of all actors involved in a war. We might all benefit one day from protection conferred by IHL, for instance as civilians, wounded, or prisoners.

[1] This section is a short adaptation of the argument presented in: Cédric Cotter, Ellen Policinski, “A History of Violence. The Development of International Humanitarian Law Reflected in the International Review of the Red Cross”, in Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies, vol. 11, n°1, June 2020, p. 36-67.

[2] For example : Elsa Brandstroem, La détresse des prisonniers de guerre en Sibérie (1920) ; H. Cuénod, L’internement en Italie des prisonniers du « Heimai-Maru » ; (1921); Charles Burckhardt and Georges Burnier, Visite des camps de prisonniers helléniques en Anatolie (1923); Lucien Cramer, La visite des prisons du Monténégro (1925) ; Renée Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre centraux en Russie et en Sibérie et des prisonniers de guerre russes en Allemagne (1920); Lucien Cramer, L’achèvement du rapatriement général des prisonniers de guerre par le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (1922); Renée Marguerite Frick-Cramer, A propos des projets de conventions internationales réglant le sort des prisonniers (1925).

[3] For example : Appel contre l’emploi des gaz vénéneux (1918) ; Réponses à notre appel contre l’emploi des gaz vénéneux (1918); Réponse de l’Allemagne à notre appel contre l’emploi des gaz vénéneux (1918) ; K de Drachenfels, La guerre chimique (1927); K de Drachenfels, La Croix-Rouge et la guerre chimique (1927); Colonel Fierz, L’utilisation d’édifices privés pour la protection de la population civile contre l’action de la guerre chimique (1929) ; Dr Sieur, Des instructions à donner aux populations civiles par conférences, affiches, tracts et films, sur les moyens de se protéger contre la guerre chimique (1929) ; Dame Beryl Olivier, Organisation d’un service de secours en cas d’attaque par les gaz. Soins aux gazés. Postes de secours. Abris collectifs. Equipes de désinfection (1937) ; Dr Sudre, Organisation générale d’un service de secours en cas d’attaque par les gaz. Soins à donner aux gazés. Postes de secours. Abris collectifs. Equipes de désinfection (1937).

[4] For example: Georg Ruth, Frais de la protection de la population d’une ville d’un million d’habitants contre les bombes brisantes, lourdes, gaz et incendies (1929) ; Franklin D Roosevelt, Limitation des bombardements aux objectifs militaires: appel du président des Etats-Unis (1939).

Muchas Gracias por compartir el articulo

Very interesting article and subject!

Like everyone, I totally agree and understand how IHL is enormously contributing on the respect of law in the time of the war and its dramatic consequences when is not respected.

Although the spirit of war remains, I think the IHL had also contribute to wage war around the world, especially when it come to engage, take responsibility or decide to go to war! I would like to read/hear about the development on this matter. Thanks