I remember the first time I visited Hiroshima. It was a sweltering week toward the end of August 2012. Government officials, civil society activists and survivors had recently marked the 67th anniversary of the nuclear explosion that devastated the city in 1945. I was there to take part in the World Congress of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW)—a global federation of medical groups that was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985 for its effort to raise awareness of ‘the catastrophic consequences of atomic warfare’.

I was working for the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) at the time, and I thought I knew all I needed to about nuclear weapons. Motivated by youthful arrogance and an urge to leave my mark on the world, I had convinced myself that we could ban nuclear weapons if we just wanted it enough.

I no longer remember what I had expected to discover in Hiroshima. But as I was driven from the airport in an aging Toyota Comfort fitted with the white, embroidered seat covers so characteristic of Japanese taxis, the first thought that struck me was how utterly normal – how unmarked – the city looked.

Crossing Tsurumi Bridge into Naka Ward, the site of the 1945 blast’s epicenter, I saw a typical Japanese city teeming with cute, matchbox-looking cars, glossy skyscraper hotels, sake bars and okonomiyaki restaurants packed in neon-lit lanes. With my car window rolled down, I watched people going about their daily business, as if nothing out of the ordinary had ever happened in the neighborhood.

I remember thinking to myself, ‘is this really Hiroshima? Can this really be the city I’ve seen devastated, “flattened and smooth like the palm of a hand”, in all those black-and-white photos?’

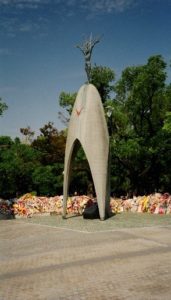

It was only later that day, as I walked across the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, that I started to notice the scars left by the 1945 nuclear explosion. I looked through the massive saddle-shaped Memorial cenotaph, leading the eye through a vacuum of emptiness, meekly promising not to ‘repeat the error’. Moving north, I saw the monument built to commemorate the unbearably high number of child victims from the nuclear explosion. It was surrounded by thousands of colorful paper cranes, all folded to fulfill 12-year old Sadako Sasaki’s dying wish for a world without nuclear weapons. On the other side of the Motoyasu River, I looked up at the famous skeletal remains of the A-Bomb Dome, in a constant state of near-collapse, a symbol of the transient nature of painful memories.

These were the visible scars of Hiroshima. However, it wasn’t until I started to listen that I realized the real impact of the explosion was not to be found in the city’s monuments, but in the minds of its people.

In the following days, I heard many testimonies of the victims and survivors of the nuclear explosion—the hibakusha. Their testimonies would shake me to my core, forcing me to confront my own prejudices: In my rush to devise a plan for how nuclear weapons could be banned, I had forgotten to ask the more fundamental question of what nuclear weapons really mean for humanity.

I would come to realize from these discussions that there existed in my own – and, I would later discover, the public – imagination, two distinct and partially conflicting ‘mental images’ of nuclear weapons, to borrow a term from the American writer Walter Lippmann. One is based on the testimonies of the hibakusha and the rules and principles of international humanitarian law; the other, on the fear of a world-destroying nuclear war.

The fact that the real meaning of nuclear weapons is not yet settled in the public imagination may explain, for example, the seemingly paradoxical findings from the ICRC’s Millennials on War survey. While the survey demonstrated widespread consensus among millennials that nuclear weapons are a threat to humanity – with 84 percent of respondents answering that the use of nuclear weapons in wars or armed conflict is never acceptable — almost half of those surveyed also held that nuclear weapons are an effective instrument of deterrence.

The co-existence of these two ‘mental images’ explains why the fault lines in this debate are so entrenched between proponents and opponents of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons and between believers and critics of nuclear deterrence. The irreconcilable nature of the debate and lack of common ground between these camps is due to the fact that these groups mean two different things when they refer to ‘nuclear weapons’.

An effects-based framing: the call for nuclear prohibition

The first ‘mental image’ is an effects-based understanding of nuclear weapons – one focused on the documented consequences of nuclear weapons as a means of warfare. This framing is based on the evidence of suffering and devastation caused by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, evoked by the testimonies of the hibakusha and the accounts of those that attempted, in near-impossible conditions, to alleviate the pain of those dying and injured.

The archives of the ICRC offer an unsettling glimpse into the horrific reality behind this image. A few weeks after the bombing of Hiroshima, ICRC delegate Fritz Bilfinger arrived in Hiroshima to assess the damage. The telegram he sent back to Dr. Marcel Junod, the ICRC Head of Delegation in Tokyo, paints a chilling picture:

“city wiped out; eighty percent all hospitals destroyed or seriously damaged; inspected two emergency hospitals, conditions beyond description, full stop; effects of bomb mysteriously serious, stop.”

From the perspective of Junod, who travelled to Hiroshima a few days after he had received Bilfinger’s telegram to assist the victims, nuclear weapons were a weapon amongst other inhumane weapons. Admittedly a horrific and uniquely destructive weapon, but still a weapon, comparable in kind to the poison gas used with cruel effect during the First World War. From this perspective, the question of nuclear weapons became a relatively straight-forward one of whether this particular tool of war, given its consequences and in light of the agreed rules of war, should be allowed for use in armed conflict.

No stranger to the horrors of war, Junod himself seemed to have had no doubt about how to answer this question. In his journal reflections from his experiences in Hiroshima, he appealed for nuclear weapons to be banned outright—a position later adopted by the ICRC and the entire Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

A fear-based framing: the theory of nuclear deterrence

In the years and decades following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the effects-based framing of nuclear weapons espoused by Junod would be challenged by an alternative understanding – an image informed not by the lived experiences of the hibakusha and other eye witnesses, but by the fear of an unprecedented, world-destroying nuclear war.

The seeds of this alternative framing of nuclear weapons originate in the minds of some of those that first developed them. After having watched the fireball from the Trinity nuclear test in 1946, Robert J. Oppenheimer, the head scientist of the Los Alamos laboratory, turned to Sanskrit scripture to make sense of what he had seen: ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds’.

Fueled by the fear of an all-out nuclear war caused by the dramatic expansion of nuclear arsenals during the Cold War, a fear-based framing of nuclear weapons took hold of the public imagination. In the minds of nuclear policy makers and civil society activists alike, the use of nuclear weapons was increasingly understood in eschatological terms as an unimaginable ‘doomsday’, ‘apocalypse’, or ‘Armageddon’.

This discursive turn in the nuclear weapons debate had several consequences. As noted by Nina Tannenwald in her seminal study The Nuclear Taboo, the understanding of nuclear weapons as an exceptional – indeed, incomparable – weapon, gave rise to an increasingly strong ‘taboo’, an implicit, normative prohibition against the use of nuclear weapons. The gradual emergence of this taboo explains, according to Tannenwald, why nuclear weapons have not been used in an armed conflict since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

However, while delegitimizing the use of nuclear weapons, the framing of nuclear weapons in terms of an unprecedented and unimaginable doomsday actually legitimized their possession.

According to the logic of what would, in the years following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, become known as the ‘theory of nuclear deterrence’, no government in its right mind would ever risk a conflict to escalate into a nuclear war, precisely because of the unacceptable devastation that would be visited upon all humankind by such a war.

By hypothesizing that international peace and stability required the constant threat of its antipode – all-out nuclear war – the theory of nuclear deterrence made it possible to view the threat of use of these weapons as a ‘necessary evil’ and a symbol of responsibility, rationality and power. The extreme threat of nuclear war would not only guarantee a future non-use of nuclear weapons, but also a perpetual state of equilibrium between the States that possessed these weapons.

An abstract battlefield, above the law?

This fear-based framing of nuclear weapons turned the question initially posed by Marcel Junod on its head. What had started out as an evidence- and effects-based debate about the legitimacy of the use of nuclear weapons in armed conflict shifted into a highly speculative debate about how the threat of total annihilation could be used to prevent war in general, and nuclear war in particular.

By framing nuclear weapons not as an inhumane means of warfare but instead as an abstract construct outside and beyond any real-world battlefield considerations, the fear-based framing lifted nuclear weapons out of the conceptual framework – international humanitarian law – that had been tried and tested to limit the harmful effects of armed conflict. Limits could not, after all, be imposed on an absolute.

This discursive turn pre-empted – for many years – any attempt to turn Junod’s appeal for an outright ban on nuclear weapons into a serious policy proposal. By positing that international peace and stability required the constant threat of use of nuclear weapons, nuclear abolitionists were left with the impossible task of proving a logical fallacy: to substantiate that their call for the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons would not imperil global security – or even worse, lead to a third world war.

Back to reality: fighting for the collective future of humanity

Many people have become accustomed to thinking about nuclear weapons in terms of an unimaginable doomsday, seemingly forgetting a harsh reality: Nuclear weapons have been used, twice, causing not only entirely imaginable, but extensive, actual and long-term suffering amongst the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Yet despite their very real consequences, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki happened a lifetime ago. Even with the recent ruling of the Hiroshima District Court to recognize dozens of additional survivors from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the day will soon come when there is no one left to tell the first-hand accounts of suffering and devastation caused by the attacks. This leaves those who have listened to the hibakusha with a special responsibility to ensure that their stories are not lost. And a responsibility for the rest of us to frame policy on nuclear weapons not by the fear of a world-destroying nuclear war, but by the all too real consequences of their use.

In fact, it was only when the testimonies of the hibakusha and the reality of the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons were reinserted as the starting point for international discussions about these weapons that the proposal for a total ban regained its appeal. The joint efforts of States, international organizations, civil society and researchers over the past ten years to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian impact and change the discourse represent a strategic move to cultivate a common understanding of nuclear weapons as horrific and unjustifiable means of warfare.

As stated by the former ICRC President Jacob Kellenberger in his historic speech to the Geneva Diplomatic Corps ahead of the 2010 Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty:

“The currency of [the nuclear weapons debate] must ultimately be about human beings, about the fundamental rules of international humanitarian law, and about the collective future of humanity”.

The adoption, seven years later, of the landmark Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was a concrete result of these efforts. The entry into force and future impact of this Treaty will depend on whether its proponents manage to keep the testimonies of the hibakusha and the evidence of humanitarian consequences front and center in the public imagination.

As Mrs. Keiko Ogura, who was eight years old when she witnessed the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, told us during my last visit: “I am a witness. Now, by listening to me, you are a witness too. I urge you to take action to ensure that the tragedy of Hiroshima is never repeated”.

See also

- Magnus Løvold, Courage, responsibility and the path towards a world without nuclear weapons: a message to youth, August 21, 2019

- Helen Durham, The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons one year on: Reflections from Hiroshima, September 20, 2018

- Elizabeth Minor, The prohibition of nuclear weapons: Assisting victims and remediating the environment, October 10, 2017

- Ellen Policinski, Majority of governments vote for negotiations to prohibit nuclear weapons, August 29, 2016

- Ellen Policinski & Vincent Bernard, Nuclear weapons: Rising in defence of humanity, July 27, 2016

Comments