The term “fake news” has been a constant presence in the media for several years now. The deliberate spread of false information seems to have become one of the great perils of our time. Yet the issue is nothing new. In fact, all conflicts give rise to propaganda, in which fake news is mixed in with rumours, information becomes a real weapon of war and the facts seem to be entirely relative. The First World War was no exception and many historians have taken an interest in the spread of rumours about atrocities perpetrated by the enemy, brainwashing and how propaganda was received by civilians at the time.

Prisoners of war: Victims of fake news

Information wars did not spare the humanitarian sector. The radicalization of conflict and the way the enemy was portrayed to the population negatively influenced the treatment of prisoners of war. Increasingly harsh cycles of retaliation against millions of people deprived of their liberty were backed by propaganda campaigns that justified such measures. Whereas all warring parties were responsible – to varying degrees – for worsening conditions of internment, they were quick to complain openly when their own citizens were the ones to suffer. At least three types of propaganda were seen: the first dehumanized the captured enemies; the second condemned the poor treatment of prisoners at enemy hands; and the third defended the conditions of internment on its own soil. Hundreds of leaflets, reports and newspaper articles claimed to uncover the truth or to somehow set the record straight, inevitably painting the picture of a noble nation battling barbaric and deceitful enemies. Just as inevitably, these publications were systematically condemned by the opposing party as soon as they appeared.

In the middle of this chaos, it became almost impossible to sort fact from fiction, and to know for sure what internment conditions were really like. This lack of clarity plunged the relatives of prisoners into great anxiety. They desperately wanted to know if their loved one was healthy, getting enough food and being held in hygienic conditions. Yet the answers they received were contradictory and the truth of government rhetoric and press reports was soon called into question.

An ICRC delegate visits German prisoners of war at Beni-Amar Camp, Morocco, during the First World War, 1914-1918. At the request of the German government, the ICRC sent three pairs of delegates on simultaneous assignments to Morocco (Dr Blanchod and Dr Speiser), Tunisia (Dr Vernet and Dr R. de Muralt) and Algeria (Mr P. Schatzmann and Dr O.L. Cramer).

The ICRC’s response

The ICRC could not remain indifferent in the face of the families’ need for answers and the suffering caused by the barrage of rhetoric. So it decided to counter the propaganda war by sharing its own observations. Firstly, it engaged in discreet but sustained humanitarian diplomacy with governments, patiently presenting its views, observations and suggestions for improving the situation of prisoners.

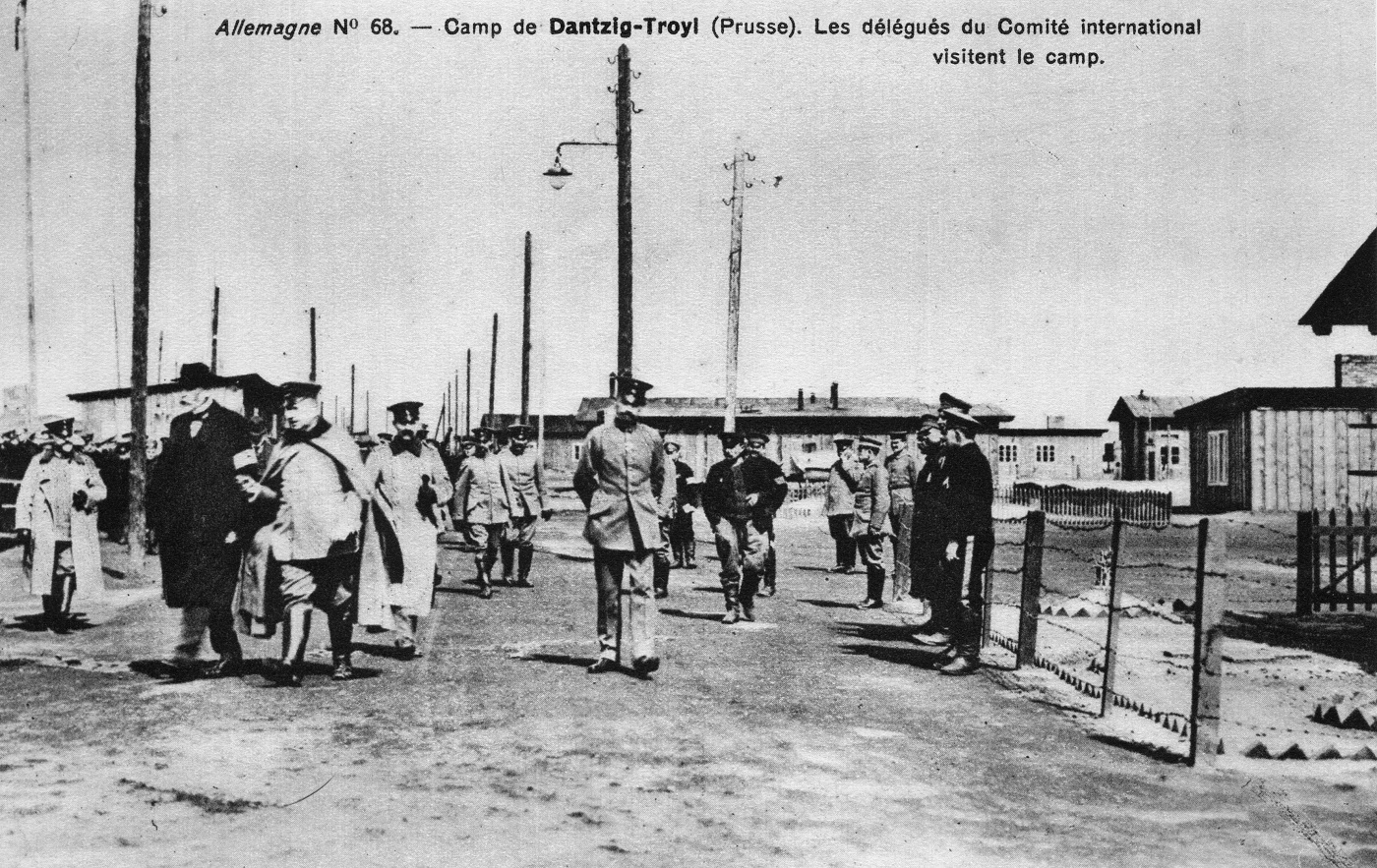

But to reassure the families, the ICRC also – and especially – needed to make its observations public. It used all possible means at its disposal to do so. The first platforms it used were the Bulletin, now called the International Review of the Red Cross, and the Nouvelles, the weekly journal of the International Prisoners of War Agency. The Nouvelles was widely distributed to warring governments, National Red Cross Societies and the press; it highlighted the real conditions in camps, presented the facts and even featured photographs.

In fact, photos became a highly effective form of counterpropaganda, as they were presented as indisputable evidence. Those taken by ICRC delegates were hugely successful, not only being published in the Nouvelles but also being sold in the form of postcards. By January 1916, there was a catalogue of over 140 different postcards featuring life in the camps. After some tough negotiations, the ICRC even managed to convince the warring parties to send in further images for distribution.

Last but not least, the ICRC was able to make use of reports written by its delegates upon returning from the field. Whereas confidentiality was previously a real trademark of the organization, the reports produced during the First World War were made public so as to reach as many people as possible. This was because: (a) they were aimed not only at governments, but also at civil society; (b) the sharing of objective and balanced content was intended to counter the information war; and (c) they were meant to reassure families of the real conditions in which their loved ones were being held.

True objectivity?

How could the ICRC guarantee that the information it was sharing was accurate? Several factors leant weight and credibility to its communications. Contrary to most propagandists and rumour-mongers operating at the time, ICRC delegates were actually present on the ground: they were visiting the camps in person, comparing the conditions of one camp to another and able to put their observations into perspective. Their reports were filled not with rumours, but with information gathered first-hand and detailed observations of what they had actually seen – something that they consistently stressed. As one report from the time indicates, “It is impossible to separate the truth from the mass of self-serving and impassioned allegations. You have to see it for yourself, gather the facts, note down reliable data, verify claims made and, above all, take account of what you are witnessing with your own eyes.”[1]

The delegates never failed to recall the intrinsic objectivity of their work. They considered themselves neutral both as Swiss citizens and as representatives of an international organization whose work had an impact beyond belligerency; in other words, both their nationality and their ideals spurred them to act with neutrality and impartiality. From 1915 onwards, delegates began operating in pairs, with French- and German-speaking Swiss citizens joining forces, thus further guaranteeing a certain balance and objectivity in their work.

This effort to establish the facts and uncover the truth had a mixed reception. The warring parties welcomed the ICRC’s observations when they appeared to support their own propaganda but challenged them when they were perceived as not critical enough of the enemy’s treatment of prisoners. There is barely any record in the archives of how prisoners’ families reacted, but there are several indications that the ICRC was considered a reliable source of information.

Obviously, the ICRC’s observations did not reflect the whole picture. Even at the time, the delegates’ reports were criticized and deemed to be sugar-coating the truth. The desire to reassure prisoners’ families was perhaps not entirely compatible with the desire to describe camp conditions as objectively as possible. The warring parties also kept visits as contained as possible, keeping the least savoury aspects of camp life out of view. It is also possible that the delegates, who were very much of their time and sometimes slightly naive, were actually convinced by their claims. Lastly, many camps and labour detachments were never visited, simply because there were too many of them. Nevertheless, however flawed they may have been, the ICRC’s efforts to “set the record straight” undeniably helped to counter the fake news generated by the propaganda war.

Mr Schatzman, ICRC delegate, with Russian and Bulgarian prisoners of war at the British camp of Dudular, Salonika. Post-First World War, 1914-1918.

Conclusion

Even though the term “fake news” was not yet in use between 1914 and 1918, the problem certainly already existed. Controlling information has always been, and continues to be, a method of warfare – but the way information is circulated has changed dramatically in the space of a century. During the First World War, the warring parties had total control over their press and propaganda, effectively censuring what they liked. Nowadays, it is much more difficult to control information. Social media have taken on increasing importance, giving everyone the opportunity to be their own journalist. While fake news is often the fruit of some highly elaborate propaganda strategy, it has become easy to pass it on without worrying if it is true or not – sometimes unintentionally – and harder to counter.

Since 1918, the ICRC’s communications have also evolved a great deal. Its improvising approach during the First World War has been replaced by proper communication strategies, whereby information is carefully selected for public consumption. Delegates’ reports are now confidential and there is a whole team of people working specifically on public communication, including social media.

While the world has changed, and the ICRC with it, some things nevertheless remain the same. As in 1918, today’s delegates still have to base their observations on what they actually see and adhere to the principles of neutrality and impartiality, which underpin their work. The ICRC’s remarks are still carefully examined before being shared; and they are still highly reliable because the organization is present on the ground, working directly with victims and witnessing their suffering first-hand. Sadly, there are still also those who seek to manipulate what the ICRC says. Lastly, as in 1918, the ICRC still has the sole aim of bringing assistance and protection to victims of war and an obligation to share its observations on the consequences of armed conflict as objectively as possible.

[1] Translated extract from a report by ICRC delegates Mr F. Thormeyer and Dr F. Ferrière Jr. on their visits to prison camps in Russia between October 1915 and February 1916, available in French only: Rapport de MM. F. Thormeyer et Dr F. Ferrière junr. sur leurs visites aux camps de prisonniers en Russie, octobre 1915 à février 1916, Eighth series, Librairie Georg & Cie, Geneva / Librairie Fischbacher, Paris, March 1916, p. 6.

For more information:

Cotter, C., (S’)Aider pour survivre: Action humanitaire et neutralité suisse pendant la Première Guerre mondiale [Helping (oneself) for the sake of survival: Humanitarian action and Swiss neutrality during the First World War”], Georg Éditeur, Chêne-Bourg, 2018.

Comments