In time of war, a single decision can change the course of a life forever.

In early 1941, Frank Evans and his wife, Henriette Edith (known as Joan), a British couple living in Argentina, decided to cross the Atlantic to get back to Britain. Joan’s parents had emigrated to Argentina in 1913 when she was just a year old. Frank, on the other hand, had travelled to Argentina in 1931 to work as a railway bridge engineer on projects in Argentina and Uruguay.

The couple met in 1934 and fell in love straight away – a real case of love at first sight.

Frank’s contract was coming to an end and he thought going back to Britain would be for the best. He also wanted to serve his country, which was now at war, and he was planning to sign up. There was never any doubt that Joan would go with her husband.

To put the situation into context, Britain was desperately in need of supplies from America and the Atlantic had become a battleground. The Allied ships were suffering heavy losses from attacks by German ships and submarines. Between mid-1940 and mid-1941, German submarines successfully stopped 3 million tonnes of cargo from reaching its destination. For every new ship that entered into service, three or four others were sunk.

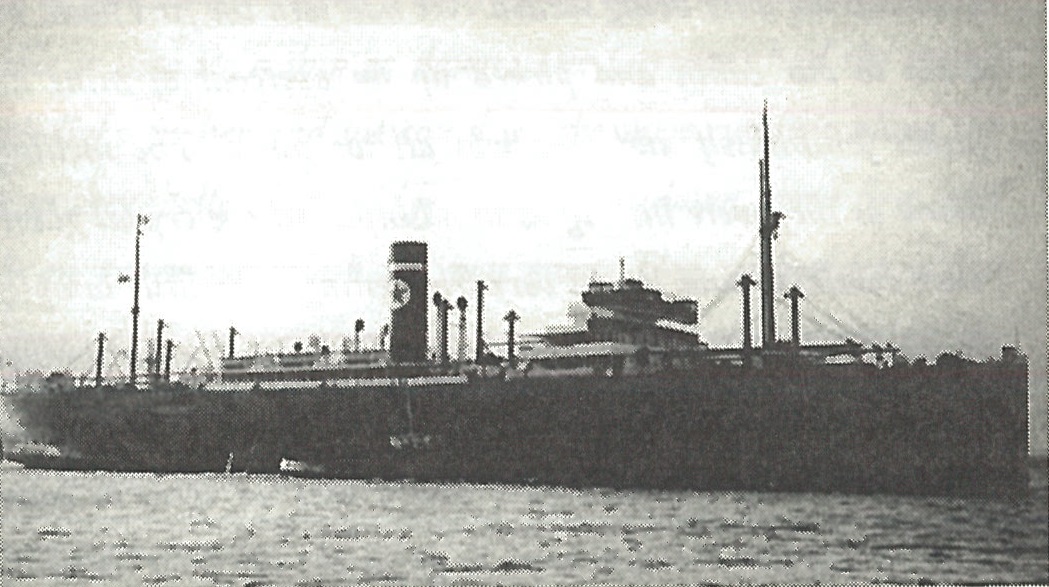

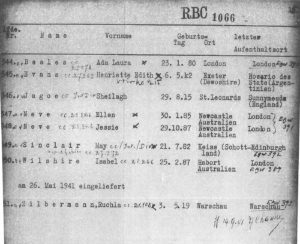

On 16 January 1941, Joan and Frank Evans, optimistic and apprehensive in equal measure, boarded the SS Afric Star in Buenos Aires. It was a British cargo ship belonging to the Blue Star Line company and carrying a cargo of meat and butter. On board were 72 crew, two naval gunners and two passengers. A third passenger, Sheilagh Jagoe, joined in Montevideo.

The journey was calm and trouble-free until the ship reached the west coast of Africa. On 29 January 1941, the ship was south of the Cabo Verde islands when it encountered a ship flying the Russian flag. The flag was quickly switched to a German one and the ship started firing at the British steamer. Their attacker was the Kormoran , a merchant ship acquired by the German navy at the beginning of the war and converted into an auxiliary cruiser. By the time it met the Afric Star, its mission was well underway, and it had already sunk two boats.

The journey had become a nightmare. The passengers and crew of the Afric Star had to abandon ship, climbing into lifeboats and then boarding the German cruiser. The Afric Star had sunk, and all on board were now in enemy hands.

The passengers were separated. Frank was put in the hold with the crew and the two women were confined to the sick bay.

The Kormoran sank another ship and a new set of prisoners joined those from the Afric Star. The prisoners were then transferred to the Nordmark and then to the Portland. Joan and Frank were allowed to see each other from time to time. The Portland was soon carrying 327 prisoners captured from different boats.

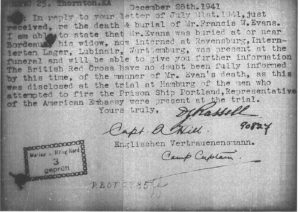

On 14 March 1941, some of the captured sailors aboard the Portland attempted a mutiny. The German guards retaliated and fired at the prisoners at the back of the hold. Two men were killed: Frank Evans and Arthur Freeman, a sailor.

Joan had no idea of the tragedy that had befallen her husband. She finally heard the terrible news when the Portland docked in Bordeaux the next day. She was engulfed by a deep sense of shock and loss.

The prisoners were transferred to the Frontstalag 221 camp in Saint-Médard-en-Jalles, together with the bodies of the two men. Joan and Sheilagh, however, were taken to the nearby Convent of Eysines. Thanks to an intervention by the French Red Cross, Joan was able to attend her husband’s funeral.

In her first letter to her mother in Argentina, Joan wrote: “I cannot tell you how I feel. It just seems as though a part of me is gone and I have no more to live for …”

This letter took four long months to reach its destination, during which time Joan’s parents in Argentina had endured weeks of anguish, knowing the Afric Star had been sunk by the Germans. They finally received the news that Joan was alive and in enemy hands in June 1941.

The female prisoners were moved by train from France to Germany, travelling first to Bremevörde and then to the German prisoner-of-war camp Stalag X‑B, near Sandbostel. Joan spent the early days of her internment in a fog of grief and sadness. On 19 April 1941, the women left Stalag X‑B and were moved from prison to prison, malnourished and suffering harsh conditions. On 12 May 1941, they finally arrived at the internment camp in Liebenau, near the town of Tettnang and a stone’s throw from Lake Constance.

The Germans had established Ilag V Liebenau Camp in a former psychiatric asylum run by nuns. The camp was used for female internees belonging to the enemy, particularly the British.

The living conditions in Liebenau Camp were good, and significantly better than the conditions they had endured in the previous prisons.

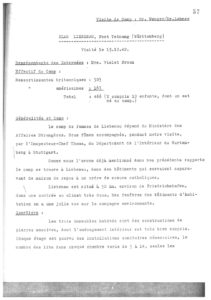

An extract of the visit report by ICRC delegates following their visit to Liebenau Camp, ACICR C SC, Allemagne, Wk. V, RT

Traumatized by the loss of her husband, Joan was unaware that she was pregnant. She found out in August 1941 during a visit to the doctor. Knowing that she was carrying Frank’s child gave her a new sense of purpose – something to live for.

For a while, she hoped that the Germans would let her go because she was pregnant, but those hopes were soon dashed.

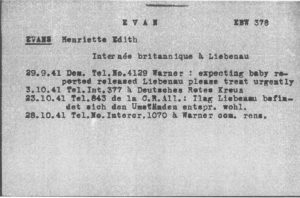

Throughout her pregnancy, Joan was cared for by her friends in misfortune: Sheilagh Jagoe, of course, and particularly by Isabel Wilshire, one of the older internees who was like a substitute mother to her. As this record from the ICRC’s Relief Division shows, Joan received Red Cross parcels containing supplies, which included clothes, knitting wool to make items for the baby and fortifying tonics.

A letter from the ICRC’s Relief Division explaining the need to send fortifying tonics to Henriette Evans, ACICR B SEC S, SG 15

© CICR, A photo of the women in Liebenau Camp receiving their relief parcels, ACICR V-P-HIST-03517-09A

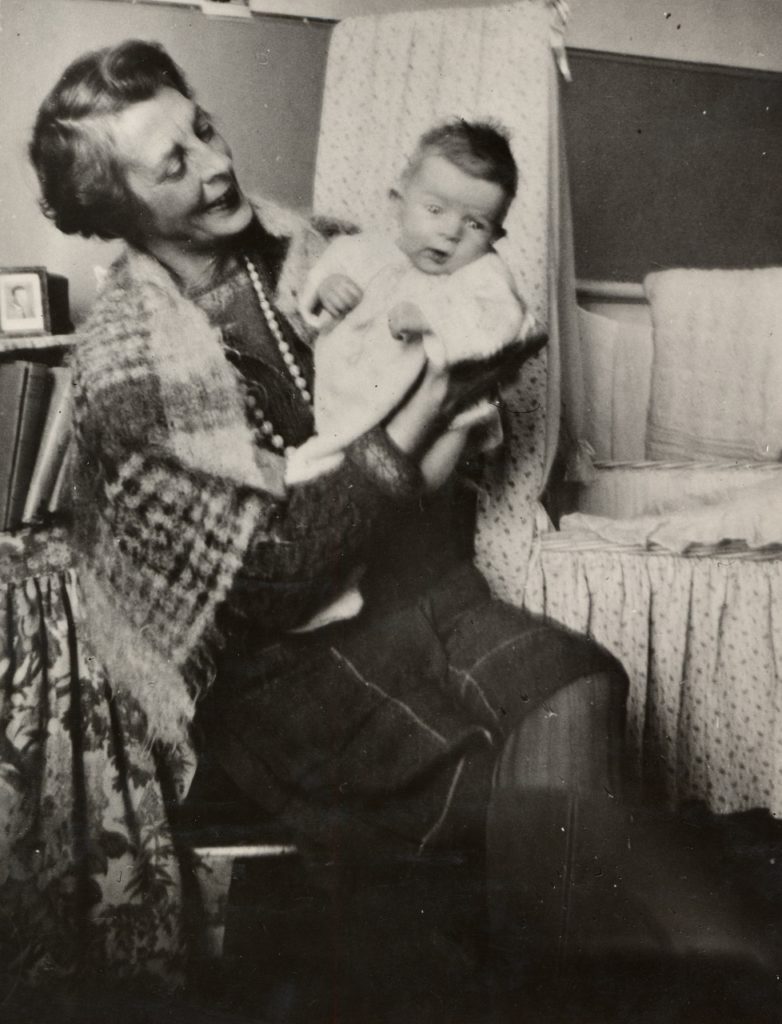

As her pregnancy progressed, Joan was moved to the camp’s hospital. Baby Frances was born on 5 December 1941. Joan named her Frances Winifred Joan Evans in honour of the baby’s late father, Frank William Jacob Evans.

Mother and baby were moved back to Liebenau Camp before Christmas. Baby Frances soon became the centre of attention. With 300 women interned in the camp, Joan had to “keep the hordes of women prisoners away from the baby”.

Several British newspapers announced the birth: the first British baby to be born in an internment camp in Germany. The ICRC photo library contains a photo of baby Frances in the arms of Isabel Wilshire with the caption: “Frances Winifred Joan, the first baby born in a civilian internment camp.”

When Frances was 11 months old, Joan learned that they were going to be repatriated as part of a prisoner exchange in Turkey. The internees packed up their paltry possessions and boarded a train for an arduous journey through Germany, Austria, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. After the prisoner exchange on the Bosporus, they were moved to Cairo, where they stayed for two months. It was here that Frances took her first steps and Joan visited the pyramids and rode a camel.

The next leg of their journey saw them travel by ship across the Red Sea to Durban in South Africa. The ship was called the José Menendez and it took them all the way back to Argentina. Frances was 14 months old when she first set foot on Argentinian soil. Joan, on the other hand, was back in her home country after two years and two months – her life now dramatically different.

To explore the stages of Joan’s two-year journey, click here and load the interactive map in full-screen mode.

Some 67 years later, Frances Evans tells her parents’ tragic story in her book, entitled Quiet Endurance. This detailed and moving story is a must-read. The book is available in the ICRC’s library.

We are very grateful to Frances Evans Bengtsson for having shared her story and her book with us.

Read more about Sheilagh Jagoe, the third passenger on the SS Afric Star, in A perilous journey across the Atlantic, part 2.

This is an incredible story of tragedy and hardship. I came across it when researching my Great-Grandfather Walter Freeman. Walter married his third wife Winifred during WW1 and they had a son Arthur Herbert Freeman. I discovered he had joined the Merchant Navy and died when serving on SS Afric Star. Thanks to you I now know that he did abandon his ship but was sadly the sailor who was killed in the failed mutiny along with Frank Evans. Thank you!

Thank you for sharing this story. I came across it while researching a British civilian internee of Liebenau, Violet Newton. Violet was evacuated to England aboard the Swedish Cruise liner, Gripsholm flying under the Red Cross Flag. Keen to learn of her time in Liebenau this was of great interest. Thank you.