History and photography are undeniably intertwined; historians often lament, unsurprisingly, that photography was not invented earlier.[1] Visitors to the ICRC’s online audiovisual archive soon become immersed in the organization’s history. Among the Second World War photos of prisoners of war (POWs) are some surprises. Photos of POW camps were mostly taken by delegates to document camp visits and detention conditions. Often attached to visit reports, they also reflect the subjective vision of the photographer. Most photos document the daily routine in a POW camp: work, meal times, sporting and religious activities. It is the photos of prisoners in costume that come as a surprise.

The medium of theatre was just one of the ways through which POWs expressed themselves creatively.[2] Given the harsh reality of prison life, theatre represented a therapeutic escape for prisoners. Andréas Kusternig reminds us that “theatre and dance also served to bring a little joy to the gloom of daily life and light up the eyes of the spectators”.[3]

This article analyses some of the photos taken during theatre performances and draws on the ICRC’s visit reports to put these photos into context, while shining a light on this little-known pastime.

Drama emerges in the camps

The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of 27 July 1929 contains 97 articles, covering issues from the organization of camps to the repatriation of POWs. Article 17 on the intellectual and moral needs of POWs allowed theatre to develop in camps: “Belligerents shall encourage as much as possible the organization of intellectual and sporting pursuits by the prisoners of war.”[4] In short, provided the detaining state had ratified the convention, POWs were allowed to enjoy themselves.

Professional artists often counted among the ranks of prisoners. Instinctively, they would start singing in their dormitory in the evening, vividly telling a story or sketching their fellow prisoners. Little by little, others would be drawn in, gathering round and forming groups based on their interests. Whether amateur or professional, each one had something special to offer. This is just one of the ways that theatre groups emerged. In another more common scenario, a leader would see that the men were in need of fun to keep their spirits up[5] and would organize intellectual or sporting activities.

Putting photos into context

The photos analysed in this article do not reflect a universal experience. The photos were all taken in Europe in the Third Reich’s POW camps; no civilians appear in any of them.

The photos that follow were analysed subjectively, taking into account the composition of the image, the subjects’ demeanour and the findings of the related ICRC visit reports. These visit reports were intended for both the state detaining the POW and the POW’s home country. The original reports were “cleaned up”, i.e. reviewed by the ICRC headquarters in Geneva before being sent to the belligerents in triplicate.[6]

A Parisian jaunt

V-P-HIST-E-00506, © ICRC

This photo was taken at Stalag X-B near Sandbostel in Germany. We do not know exactly when it was taken, but we can deduce from the ICRC visit reports that it was taken before 1944. The reports tell us several things. We know that the camp housed many different nationalities and the first mention of a theatre troupe appeared in 1941,[7] noting that it put on regular performances. This suggests that the troupe had been active for some time and had established a routine. By 1942,[8] the troupe had its own hut. With 50 members, including two professionals, it was larger than the average troupes of between 10 and 20 men. By June 1943,[9] the theatre troupe had installed a stage with a revolving set, built by a prisoner. This was a first for a camp, and this one certainly benefited from more resources than other Stalags. By March 1944,[10] one report indicated that the troupe had started rehearsing for a performance of Hamlet.

This information seems to be confirmed by the photo. The POWs are wearing costumes that appear to be made of proper materials, unlike the makeshift costumes seen in other camps. The costumes fit well and are not overly crumpled, which suggests the troupe had somewhere to store them. The decorative backdrop also indicates that they had the resources to get the detail right. They almost certainly had access to papers, paintings and images as reference materials. In this photo, the actors are in Paris, with the hill of Montmartre and the Sacré-Cœur in the background. The prisoners are posing in character, with two of the men assuming a feminine demeanour, while the man on the right seems to be trying to charm them while playing the guitar. Although they are in character, their smiles seem genuine; a hiatus from their daily reality.

Unfortunately, from October 1944 onwards,[11] conditions in the camp deteriorated. Overcrowding meant most of the areas intended for intellectual pursuits were used for accommodation. By 1945,[12] ICRC delegates were advocating that leisure was more necessary than ever in these particularly difficult times. Overcrowding had left only one room available for leisure activities. For obvious reasons, the theatre company and the orchestra were not able to rehearse in the same place.

Despite the diversion that a performance might offer the audience, it is important to remember that “theatrical activities did not supplant the military and political reality – quite the contrary. For example, one ‘leading lady’ who found a costume in the theatre’s collection tried to escape disguised as a Czech peasant woman [13] from a camp in northern Austria.

Cinderella’s misery

V-P-HIST-03516-23A / V-P-HIST-03516-26A,© ICRC

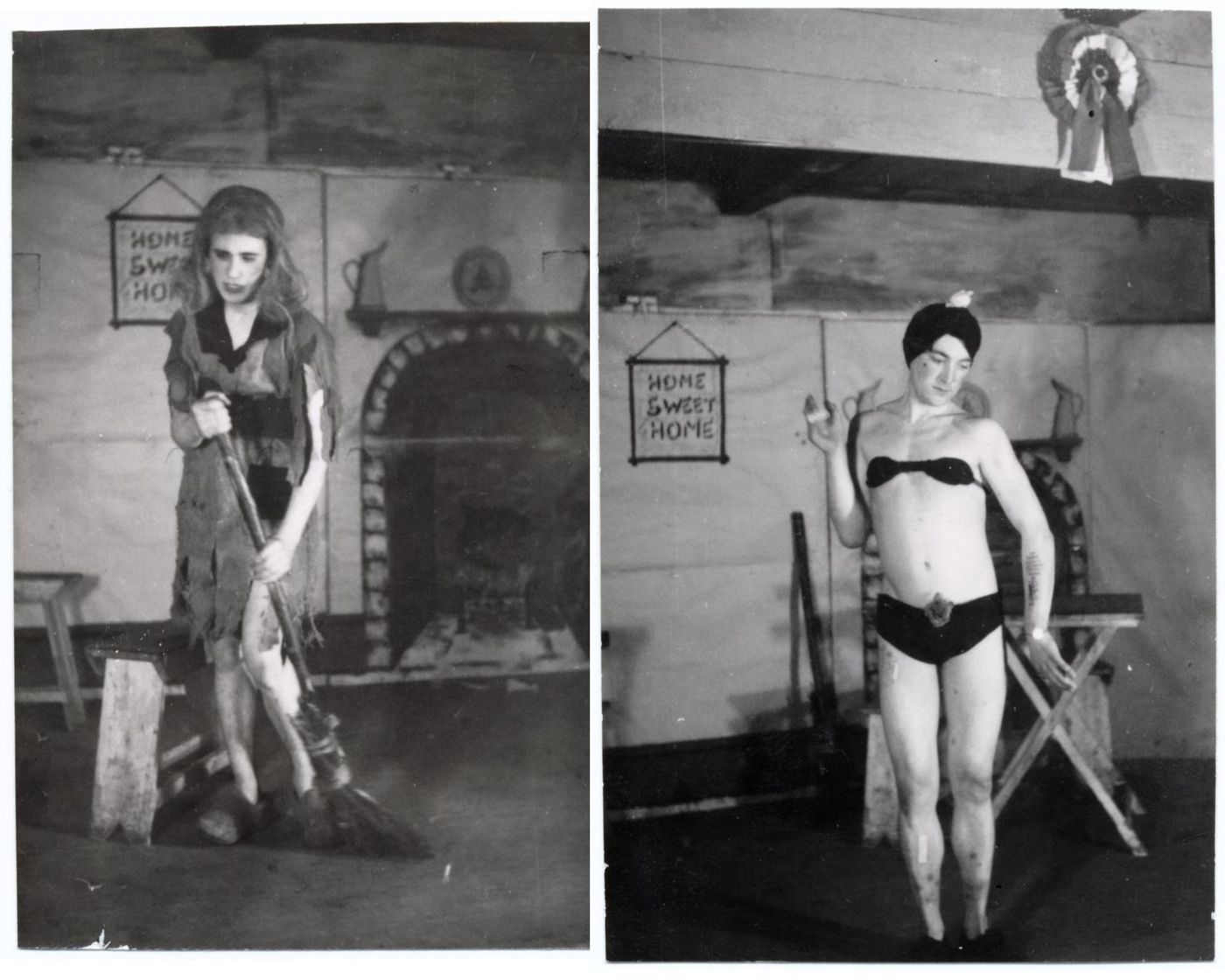

These photos were taken on 1 February 1941 at Stalag XX-A in Thorn, Poland. They bear witness to the reality of suffering in the camps. You can see great sadness in the actors’ faces, partly because they are in character, but life in the camp has also left its mark on their bodies. A theatre troupe is first mentioned in an ICRC visit report on Stalag XX-A from the same period as the photos. It states that performances took place in both French and English, and gives the example of the performance of Cinderella in English.[14]

The first photo, showing an actor wearing a worn and dirty dress, appears to be a production of Cinderella. The actor sports a blonde wig and seems to be sweeping the floor of a house, as hinted at by the embroidered “Home Sweet Home” in the background. The words confirm that the play is being performed in English and is likely to be Cinderella, as mentioned in the ICRC report. This photo perfectly fits the image we have of Cinderella as a young, blonde woman, dressed in rags, carrying out her cleaning duties.

The actor in the second photo was willing to undress for his art. Let’s not forget that these actors were, first and foremost, POWs and it would have been odd to see the men like this, particularly for the audience. Yves Durand reminds us of this in his book on the daily life of POWs: “When we see the photographs of these ‘ladies with camellias’, this ‘Madame Vidal’ kissing her ‘lover’, or the slender French cancan dancer, we understand the admiration the prisoners of war felt as they watched these actors tread the boards, not least because, having experienced an evening of emotion and probably nostalgia, they would pass these actors in the camp’s alleyways the next day, just as they had done the day before, unshaven and wearing the patched-up military garb of captive soldiers.”[15] The actor’s skimpy outfit may have shattered the illusion though, with the wounds on his legs serving as a reminder of his POW status and his need to work in the camp, like everyone else.

By July 1944,[16] the French theatre had closed because there were so few French prisoners in the camp. Following organizational changes, the British theatre was also shut down. This is the last time theatre is mentioned in the ICRC reports before the camp was liberated in February 1945.

A staged portrait

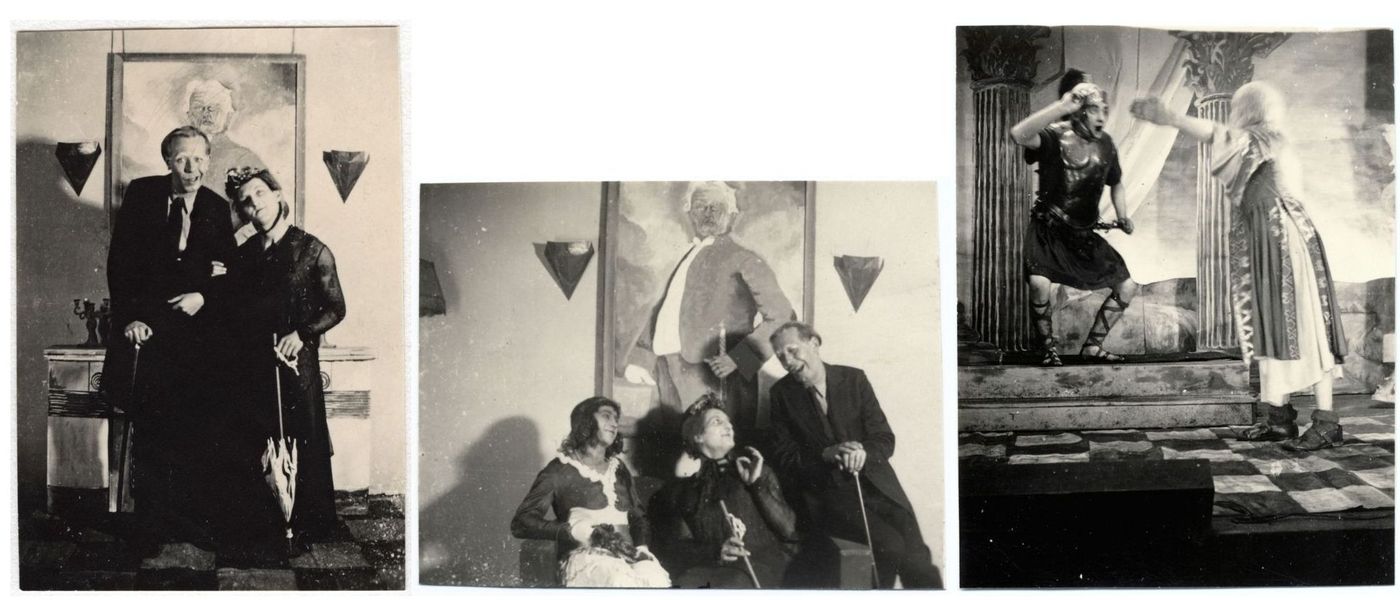

This group portrait was taken in 1943 at Stalag I-A near the village of Stablack in what was East Prussia. We can deduce from the ICRC visit reports that the photo was taken in the first half of 1943. Indeed, the report on the ICRC visit of 16 September notes that although the camp had had a theatre, an orchestra and other forms of entertainment, these facilities were no longer operational because the rooms used for these activities had to be used to house new arrivals.[17]

The ICRC visit report of 3 February 1941 mentions that “a drama company organizes performances”,[18]and the photo shows the actors wearing make-up, costumes and wigs that look professionally made. This all suggests that between the time the visit report was written and the time this photo was taken, the troupe had been able to polish its performance. Despite the limited resources available, the standard achieved in terms of aesthetics was most probably the work of the many artists in the troupe, such as painters and sculptors.

The photo probably shows all of the actors taking part in the play; Stalag troupes were not usually large. The actors seem to be posing for multiple photographers. Those on the left are looking in one direction, while the man standing in the middle holding his stage partner by the shoulders is looking in the opposite direction – the same direction as the person sitting in the foreground in a white dress. This leads us to believe that there are at least two photographers. Further to the right, we see that two actors are looking at a camera in front of them: the one that took the photo in our archives. It seems likely, therefore, that there were three photographers and that it was probably an organized photo shoot. This is only a supposition; the actors could simply have posed like that to make the composition more interesting than if they had all been looking in the same direction.

Stalag and Oflag

Stalag is a contraction of Stammlager and means main camp. It was an ordinary POW camp for soldiers and non-commissioned officers. Those in charge of Stalags often had few resources to manage them.

Oflag is a contraction of Offizierslager and means officers’ camp. These camps had more resources[19] and detention conditions were better. According to Andréas Kusternig: “Article 27 of the Geneva Convention and the officers’ code of honour prohibit forcing officers to work for those who detain them[.] They therefore had no work to do. […] [T]hey needed something, anything, to do, to keep them from going crazy.”[20]POWs in Oflags often had more time to spend on cultural activities.

Main stage and small stage

V-P-HIST-01835-01 / V-P-HIST-01836-01 / V-P-HIST-01838-03,© ICRC

These photos, taken at Oflag VI-D near the city of Münster, Germany, are dated Easter 1943. This camp held French officers as early as May 1940, but the first ICRC report to mention theatrical activities dates from 4 March 1941.[21] However, we learn from Patricia Gillet that theatre had been a part of the officers’ daily life since the camp opened: “The idle officers of Oflag VI-D set up an extremely active theatre troupe: between October 1940 and May 1942, it gave more than 230 performances of 47 different plays.”[22]

By October 1941, the theatre troupes had put on 145 performances.[23] There were two troupes, the Grande scène [main stage] and the Petite scène [small stage], making it possible to organize more performances. During their visit, the ICRC delegates admired the variety of sets and accessories in store, all built and crafted by prisoner artists who had shown great ingenuity given the resources available. Although Oflags had access to more resources than Stalags, the POWs still had to work hard to create costumes and sets to evoke the atmosphere of a grand theatre. The report of 28 May 1942 [24] indicates that many activities were organized to meet the prisoners’ intellectual and spiritual needs. Unlike other POW camps, this Oflag complied with Article 17. The theatre and the orchestra had an entire block for their activities, which certainly helped these two theatre troupes to flourish. The last ICRC report on this camp dates from 10 February 1944 [25] and informs us that the theatre was operating very well. The camp was shut down in September of that year. It is likely that the theatre remained active until its closure.

In the first two photos, we can see the actors posing in front of the same set. In the first photo, two men, presumably playing a couple, are looking at the camera. In the second photo, the actors look like they are mid-scene; perhaps it is a rehearsal, or perhaps the ICRC delegates had the opportunity to attend a performance. None of the prisoners are looking at the camera, giving the sense that the photo is a snapshot in time and not staged. The photographer has managed to capture a genuine and natural moment, despite the subjects’ make-up, costumes and role-play.

In the third photo, there are two actors who are again captured mid-scene, and somewhat blurred because they are moving. They are not looking at the camera, seemingly unaware that someone is taking their picture. The photographer has captured another candid, fleeting moment. This set is completely different, as is the style of costume. The man on the left is wearing a Roman soldier’s uniform and the man on the right a Roman toga, while the set columns show typical Roman architecture, all setting the scene in ancient times. They are in fact performing the comedy Apollo’s Holiday by Jean Bertet.[26] As these photos were taken during the same visit at Easter, we have photographic evidence that the two stages and the two theatre troupes mentioned in the ICRC visit reports existed.

Life for POWs

The visit reports show that not all POWs enjoyed the same privileges. First, there is the difference in how Article 17 of the Geneva Convention between Oflags and Stalags was applied. Applying this article was not a priority for the Stalag authorities, especially when the situation in the camp was liable to change without warning. The lack of space when new prisoners arrived was one of the main reasons for reorganizing the camps. The first spaces in line for conversion into dormitories would be those used for creative leisure activities requiring a lot of space, such as the theatre. When this happened, the authorities were quick to abandon those activities that met the POWs’ intellectual needs.

The visit reports and the photo analysis also highlight how creative the POWs were. Regardless of their scant resources, they demonstrated commitment and passion. The semblance of freedom that the theatre offered almost certainly enabled many prisoners to withstand the harsh conditions they endured in the camps. They could at least escape mentally, despite being physically confined. Yves Durand sums it up perfectly: “The collective life of the camps has produced spiritual, cultural and sporting events, of varying degrees of sophistication but often of astonishing quality. They bear witness to the extraordinary resources on which the human spirit can draw in even the most difficult situations.”[27]

[1] About, Ilsen and Cheroux, Clément, “L’histoire par la photographie” [History through Photography], Études photographiques, Vol. 10, November 2001, pp. 8–33.

[2] Allemann, Marie, ICRC CROSS-files: https://blogs.icrc.org/cross-files/artistic-expression-in-prisoner-of-war-camps-1/, accessed 31 October 2020.

[3] Kusternig, Andréas, “Entre université et résistance : les officiers français prisonniers au camp XVIII A à Edelbach” [Between University and Resistance: French POW Officers in Camp XVIII A in Edelbach] in Catherine, Jean-Claude (ed.), La captivité des prisonniers de guerre : Histoire, art et mémoire, 1939-1945, Presses universitaires de Rennes, Rennes, 2008, p. 58.

[4] https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/applic/ihl/dih.nsf/INTRO/305?OpenDocument, accessed 3 November 2020.

[5] Durand, Yves, La Captivité : Histoire des prisonniers de guerre français 1939-1945 [Captivity: A History of French Prisoners of War 1939–1945], Fédération Nationale des Combattants Prisonniers de Guerre et Combattants d’Algérie, Tunisie, Maroc, Paris, 1982, p. 306.

[6] ICRC, Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities during the Second World War (September 1, 1939 – June 30, 1947), Vol. 1, ICRC, Geneva, May 1948, pp. 238–243.

[7] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag X-B, 8 July 1941.

[8] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag X-B, 6 August 1942.

[9] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag X-B, 26 June 1943.

[10] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag X-B, 25 March 1944.

[11] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag X-B, 10 October 1944.

[12] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag X-B, 13 March 1945.

[13] Kusternig, Andréas, “Entre université et résistance : les officiers français prisonniers au camp XVIII A à Edelbach” [Between University and Resistance: French POW Officers in Camp XVIII A in Edelbach] in Catherine, Jean-Claude (ed.), La captivité des prisonniers de guerre : Histoire, art et mémoire, 1939-1945, Presses universitaires de Rennes, Rennes, 2008, p. 58.

[14] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag XX-A, 3 February 1941–16 February 1941.

[15] Durand, Yves, La vie quotidienne des prisonniers de guerre dans les stalags, les oflags et les kommandos, 1939-1945 [The Daily Life of Prisoners of War in Stalags, Oflags and Kommandos, 1939–1945], Hachette, Paris, 1987, p. 186.

[16] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag XX-A, 27 July 1944.

[17] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag I-A, 16 September 1943.

[18] ICRC Archives, C SC Stalag I-A, 3 February 1941.

[19] Durand, Yves, La vie quotidienne des prisonniers de guerre dans les stalags, les oflags et les kommandos, 1939-1945 [The Daily Life of Prisoners of War in Stalags, Oflags and Kommandos, 1939–1945], Hachette, Paris, 1987, p. 184.

[20] Kusternig, Andréas, “Entre université et résistance : les officiers français prisonniers au camp XVIII A à Edelbach” [Between University and Resistance: French POW Officers in Camp XVIII A in Edelbach] in Catherine, Jean-Claude (ed.), La captivité des prisonniers de guerre : Histoire, art et mémoire, 1939–1945, Presses universitaires de Rennes, Rennes, 2008, pp. 55–77.

[21] ICRC Archives, C SC Oflag VI-D, 4 March 1941.

[22] Gillet, Patricia, “Le théâtre dans les camps de prisonniers de guerre français, 1940-1945” [Theatre in camps for French prisoners of war, 1940–1945], in Théâtre et spectacles hier et aujourd’hui, Époque moderne et contemporaine, Actes du 115e congrès national des sociétés savantes, CTHS Paris, 1991, (ISBN 2-7355-0220-1), p. 270.

[23] ICRC Archives, C SC Oflag VI-D, 10 October 1941.

[24] ICRC Archives, C SC Oflag VI-D, 28 May 1942.

[25] ICRC Archives, C SC Oflag VI-D, 10 February 1944.

[26] ICRC Archives, Germany 1939–45. Prison camps. 10.14.c.

[27] Durand, Yves, La vie quotidienne des prisonniers de guerre dans les stalags, les oflags et les kommandos, 1939-1945 [The Daily Life of Prisoners of War in Stalags, Oflags and Kommandos, 1939–1945], Hachette, Paris, 1987, p. 173.

Comments