For decades, there has been consensus in the international community that in times of armed conflict, impartial humanitarian operations and the humanitarian personnel involved therein must not be targeted. In other words, you do not shoot at the truck that delivers food and medicine to civilians. This consensus must be respected online as well as offline, as recently affirmed in a resolution entitled ‘Safeguarding Humanitarian Data’ adopted by the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. The backbone of this consensus is enshrined in international humanitarian law (IHL).

In this post, the ICRC’s Tilman Rodenhäuser, Balthasar Staehelin, and Massimo Marelli explore how these rules impose limits on digital threats against impartial humanitarian organizations and propose legal, policy and operational measures to safeguard them against such threats.

At the International Committee of the Red Cross, we are acutely aware that impartial humanitarian organizations are not immune from hostilities. Working in some of the most complex environments to protect and assist vulnerable populations, impartial humanitarian organizations too often become victims of threats and violence.

With the digital transformation of the humanitarian sector, a new layer of digital threats is today a sad reality. In 2022 alone, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement members have been targeted in different ways, from a sophisticated data breach affecting personal data of over half a million people, to information operations that put their staff at risk, or ‘Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS)’ operations making websites or servers unavailable. Digital threats are a growing concern for many intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations, and one of the top risks in the humanitarian sector.

A threat to essential services for people affected by armed conflict

Digital operations against impartial humanitarian organizations can cause harm at several levels. They risk directly impacting the safety and integrity of humanitarian personnel and operations. Such operations can also cause harm on a much broader scale by affecting people who seek essential protection and assistance.

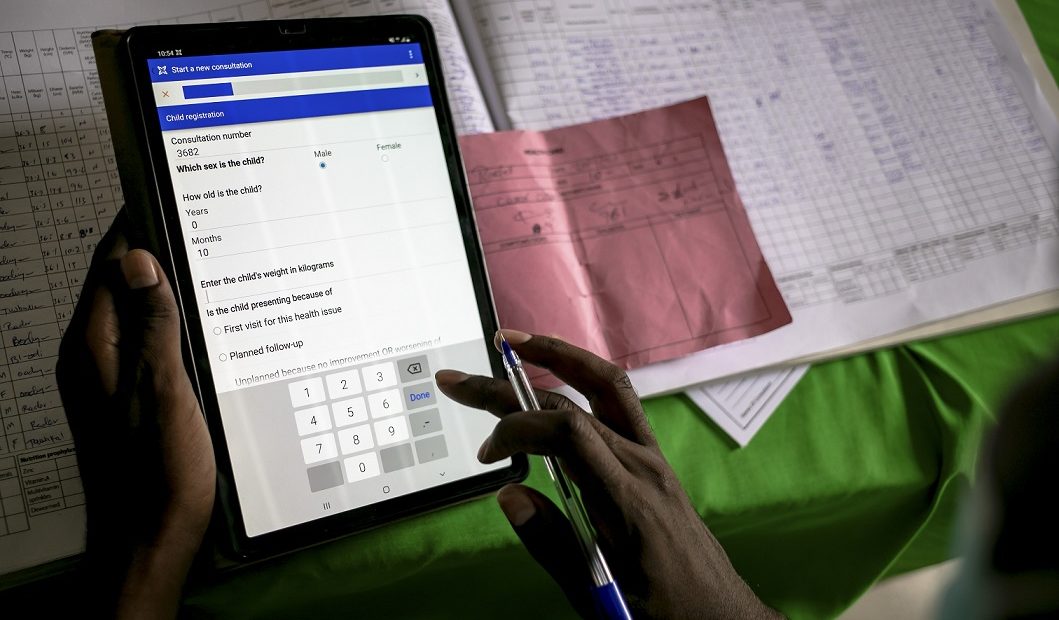

Concretely, if computer systems or databases used by impartial humanitarian organizations are disrupted by cyber operations, their relief work necessarily slows down, becomes dysfunctional, and cannot reach people at scale – or at all. One of the consequences of the 2022 breach of data hosted by the ICRC was that servers had to be taken down, systems rebuilt, and for several weeks services to locate missing family members could only continue at minimal levels, at times going back to using pens and paper. The Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement has also raised concerns (here, paragraph 3) that data breaches risk eroding trust in impartial humanitarian organizations, potentially jeopardizing access to people in need. The worst fear of people whose data is accessed – and of humanitarian organizations – is that extracted data is misused to cause harm.

Even if disinformation and threats of violence against humanitarian personnel are spread online on social media and other digital platforms, their negative impact is felt offline. In places affected by armed conflict, tensions are high, rumors spread easily, and false information falls on fertile ground. For humanitarian organizations to do their job safely, trust of all warring parties and of communities is essential. If the perception of their work changes, fueled by online or offline disinformation, humanitarian personnel can quickly be unable to leave their offices, distribute live-saving assistance, visit detainees, or bring news to people who have lost contact with a family member.

Impartial humanitarian organizations and their staff are #NotATarget

In times of armed conflict, international humanitarian law contains strong rules to safeguard impartial humanitarian organizations. In very broad terms, this legal protection under IHL consists of three layers (for more, see here and here).

First, humanitarian organizations benefit from the protection provided for civilian objects and civilians, meaning notably that their premises, the material used in their operations, and their personnel must not be attacked (articles 51 and 52 Additional Protocol I, Rules 1 and 7 ICRC Customary IHL Study).

Second, once impartial humanitarian operations have been agreed to by the concerned belligerent(s), these operations must be allowed and facilitated by the parties to the armed conflict and third States, subject to their right of control (article 70 Additional Protocol I; Rule 55 ICRC Customary IHL Study). Translated into the cyber context, experts involved in the Tallinn Manual process have interpreted this rule as prohibiting cyber operations ‘designed or conducted to interfere unduly with impartial efforts to provide humanitarian assistance’, thereby frustrating or preventing impartial relief efforts (Tallinn Manual 2.0, Rule 145).

Third, humanitarian operations, and humanitarian personnel, must be respected and protected (Article 71 Additional Protocol I, Rules 31 and 32 ICRC Customary IHL Study). This means that they must not be harmed in any way and must be protected against harm by private actors.

Depending on the circumstances, attacking humanitarian organizations may even amount to a war crime – including in the digital sphere (see articles 8(2)(b)(iii); 8(2)(b)(xxiv); 8(2)(e)(iii) Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court).

These IHL rules have long provided a necessary protection framework for impartial humanitarian organizations. Clarification is needed, however, on how they apply in the digital sphere.

Applying IHL rules to cyber and information operations

Often, the interpretation of IHL in the digital environment is done by analogizing to the physical world. Accordingly, there is no doubt that cyber operations that can be reasonably expected to cause physical damage or destruction to impartial humanitarian organizations, or injury or death to their staff, are prohibited – just as any other attack against civilians.

In many cases, however, cyber operations will not cause physical damage but rather disrupt or disable digital infrastructure. Still, directing such operations against impartial humanitarian organizations is prohibited. To start with, this is the case if the view is taken that such operations that disable digital infrastructure constitute an ‘attack’ against a civilian object, which is the view of the ICRC and several States (see here for a summary of State positions on whether such operations amount to ‘attacks’ under IHL). Regardless of the position taken on the notion of ‘attack’, such operations will likely violate the obligations to allow and facilitate humanitarian activities and to respect and protect humanitarian operations, which prohibit undue interference with their work as well as ‘forms of harmful conduct [against humanitarian organizations] outside the conduct of hostilities’ (see here, p. 329). Humanitarian operations – including staff – enjoy such strong protection under IHL because they face exceptional risks and if their work is obstructed, the negative impact on people affected by the conflict will be real.

Cyber operations targeting humanitarian data raise additional issues. If such operations involve manipulating, encrypting, or destroying humanitarian data, it would unduly interfere with humanitarian relief efforts and be prohibited (see above and here). In addition, parties that contemplate breaching humanitarian data – without damaging it – should consider that their conduct risks undermining trust in the impartial humanitarian organizations and, depending on the circumstances, put humanitarian staff in danger. This risk is particularly acute if humanitarian data is extracted with a view to targeting adversaries or civilians (see here). And even breaching humanitarian data without damaging or misusing it may be difficult to reconcile with the letter and spirit of IHL. For instance, spying on impartial humanitarian organizations would compromise the confidentiality of information, a key working modality for the ICRC that is explicitly recognized under IHL with regard to detention visits (article 126 GC III and 143 GC IV). Moreover, if States mandate an impartial humanitarian organization like the ICRC to perform services such as the tracing of missing people, these services must be facilitated and not undermined (article 81 API).

Finally, if we turn to information operations, it is clearly unlawful to use social media – or any other media – to incite violence against civilians, including humanitarian personnel (see here, para 220; and here, article 1, para. 191). Moreover, while impartial humanitarian organizations are not protected against criticism or the expression of anger, spreading disinformation aimed at obstructing or frustrating their work is difficult to reconcile with IHL. First, such operations would unduly interfere with humanitarian activities, and not facilitate them. Second, information operations may lead to harm to humanitarian personnel and consignments, for instance by inciting violence or obstruction. This would violate the obligation not to harm (i.e. respect) humanitarian operations, or – by creating false perceptions and stirring up anger against humanitarian operations – fail to comply with the obligation to protect such organizations against harm.

Multilayered responses needed

Digital threats in armed conflicts are likely to increase – against civilians but also against impartial humanitarian organizations. Humanitarians, States, and other actors must work together to ensure that the long-standing consensus on the protection of impartial humanitarian activities prevails, in law and practice, in the digital age. For as long as people affected by armed conflict need impartial and independent humanitarian relief, those who provide it must be safeguarded, including against new threats.

At the legal and policy levels, we must strive towards a clear understanding of the real harm that digital threats against impartial humanitarian organizations cause and build a robust political understanding that they are unacceptable and, in fact, unlawful. This requires dialogue at the national, regional and international levels.

Operationally, impartial humanitarian organizations have an important responsibility to adopt and implement appropriate cyber security, data protection and up-to-date strategies and processes to ensure resilience of their operations and to protect the people they serve (see here).

Finally, new threats might require innovative responses, such as a ‘digital emblem’ to signal the legal protection of medical facilities and the ICRC in cyberspace, safe environments to develop and test digital humanitarian services (such as the ICRC’s Delegation for Cyberspace), increase preparedness to manage disinformation, or a ‘sovereign humanitarian cloud’ to protect their data. Developing such solutions cannot be done by impartial humanitarian organizations alone but requires partnerships, support and collaboration by governments, and private sector, academia and civil society.

See also:

- Massimo Marelli, The SolarWinds hack: lessons for humanitarians, March 18, 2021

- Massimo Marelli, Hacking Humanitarians: moving towards a humanitarian cybersecurity strategy, January 16, 2020

- Tilman Rodenhäuser, Hacking Humanitarians? IHL and the protection of humanitarian organizations against cyber operations, March 16, 2020

Comments