Meaningful human control: Labels and specifications

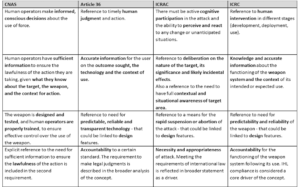

As Scharre wrote here earlier, the pace of technological change presents hurdles for the international community to be able to grasp with the legal, ethical and policy consequences of developments. Instead of trying to predict future forms of autonomous weapons, States have focused their efforts on the unchanging element in war: the human. Concerned about humans losing control of increasingly autonomous weapons, the international community is discussing ways for such a future to be prevented. This objective has been captured by different concepts, such as meaningful human control, appropriate levels of human judgment, and sufficient human control. Setting aside the labels, a closer look at the specifications of these concepts reveal many parallels, implying that the objectives of this debate are similar and that disputes are mostly confined to the margins

Underlying assumptions

The descriptions of meaningful human control in the above table describe what is generally expected of humans in the operation of (autonomous) weapons. It bears emphasis that discussions about this concept typically maintain a narrow focus on the relationship between the weapon and the operator—assessed during weapon’s use. Furthermore, the concept of meaningful human control rests upon the assumption that, in past and present operations, humans do exercise control over weapons. This is demonstrated by official statements, (working) papers, and (in)formal discussions where States and civil society members emphasize that meaningful human control is concerned with maintaining human control. Accordingly, some States and organizations consider the examination of current practices of targeting and weapons deployment a key factor in determining the meaning of the concept.

This focus on past and current operations could, indeed, shed some new light onto deliberations about autonomous weapons. If we look at contemporary military missions with manned weapon systems, it is expected that the human role reaches the threshold of meaningful control owing to the operator directly controlling the weapon system. But is that really the case and what exactly should we be looking at? Let’s move beyond abstract, semantic discussions and consider meaningful human control in operation.

A brief case study: the human role in a specific targeting mission

Let’s look at the operator’s role in a routine targeting operation where a manned F-16 aircraft carrying JDAM weapons (i.e., GPS guided Joint Direct Attack Munition) is tasked with targeting a military compound. Although it is important to note that this is a case of deliberate targeting (as opposed to dynamic), even planned targets are executed in an operational environment that changes as a result of actions from military personnel, adversary and other actors. Therefore, the dynamic targeting cycle (F2T2EA) is also part of the deliberate targeting process and, as such, will guide our vignette.

The difference between dynamic and deliberate targeting is, simply put, time. When targets are identified and developed in time, they can be included in the deliberate targeting cycle and actions against them can be scheduled. Dynamic targeting consists largely of the same steps but is more responsive than deliberate targeting since the process is used to prosecute targets that are either unexpected or known to exist in the area of operations, but were not yet detected or selected for action in sufficient time to be included in the deliberate process. Whenever the differences (and similarities) between deliberate and dynamic targeting are relevant for our brief case study, they are addressed (where space allows).[1]

The briefing

Our mission starts with a briefing. Before the operator will execute this mission, s/he will be briefed, study the data provided for them, and do last-minute preparations. The extent of information that is briefed to the pilot depends on the operational context and is based on what s/he needs to know. This can be as limited as the coordinates of an area of operations within which the operator is supposed to fly during a particular time in order to conduct dynamic missions as these arise. Such dynamic targeting missions will be briefed to the operator on the fly and will consist of as little information as possible in order to allow the operator to engage a target effectively. This could result in situations where the operator is not aware of the type of target or the context for action.

In deliberate targeting, however, the extent of information is typically more extensive due to the preplanned nature. The operator tasked with such a mission will receive a target package that typically includes:

- A description of the target consisting of all available knowledge. In our example that will be a description of the military compound;

- The target’s coordinates;

- A collateral damage estimation to provide the operator with an estimation of the expected collateral damage. In our example the risk of collateral damage is low as long as the predetermined mitigating techniques are applied.

- A recommendation of the quantity, type and mix of lethal and non-lethal weapons needed to achieve the desired effects while avoiding unacceptable collateral damage (e.g., the JDAMs).

- The joint desired point of impact used as a standard to identify aim points;

- The weather forecast that, in our example, describes a night with overcast conditions (clouds cover most or all of the sky) and heavy rainfall.

Find-Fix-Track-Target-Engage-Assess Cycle

Once briefed, the operator will execute the mission by executing the Find-Fix-Track-Target-Engage-Assess (dynamic targeting) cycle.

In the find phase the operator will navigate to the area within the weapon’s envelope (that is, the area within which the weapon is capable of effectively reaching the target). This is based on the preprogrammed coordinates making the find phase more of a navigational task.

The sensors will be focused in the fix phase to obtain a positive identification of the target. In our example, the target is already approved at the operational planning level before take-off and due to the circumstances of this case (clouded night with heavy rainfall) and with the means available (GPS-guided JDAMs) the operator will, typically, not visually confirm the target. Instead, s/he will rely on the aircraft’s systems, the weapons guidance systems, and the validation procedure at the operational level to ensure s/he is striking a legitimate military objective in a lawful manner.

Typically, the target will then be tracked to update information and maintain positive identification. The military compound is a fixed target, which makes tracking a very static exercise. The operator’s primary task is thus, still, to navigate the aircraft to the weapon’s envelope.

The target phase typically considers the relevant law and policy, collateral damage issues, and the risk to one’s own forces. In this case, the target has been vetted and validated by military personnel (e.g., intelligence personnel, legal advisers, the commander) at the operational level. Thus, the pilot merely needs to load the target coordinates (as well as impact course, angle, velocity) into the aircraft before take-off or in-flight. Depending on the collateral damage concerns, the target engagement authority is established either at a high level or at lower echelons. The operator is under the direction of tactical command, but s/he can be given discretion to act on his or her own when there is a low risk of collateral damage or friendly fires. It is thus not uncommon that in these cases—when the target cannot be visually confirmed and there is a low risk of collateral damage—the operator is allowed to strike without having to request approval to tactical command in flight. Overall, this target phase does not require active deliberations concerning legal compliance by the operator. So far, s/he’s mainly responsible for flying the aircraft to the weapon’s envelope.

Once the aircraft enters the weapon’s envelope, the process moves into the engage phase during which the target is executed. Once the aircraft enters the weapon’s envelope, the bomb’s computer will suggest the most effective time to release the bomb. For GPS guided munitions such as the JDAM, there is no need to find the target visually and then aim the weapon at the target by maneuvering the aircraft or pointing a laser beam. When a target is engaged with JDAM weapons, in weather conditions that prevent or limit usage of sensors, the situational awareness of the operator is likely to be reduced. It, therefore, cannot be realistically assumed that, in this case, the operator will see the target or its environment. The pilot simply needs to ‘pickle’ (press the switch to release the weapon) once s/he flies within the weapon’s envelope.[2] After launch, it is the JDAM’s task to process signals from satellites to keep track of its own position and to navigate towards the designated target coordinates. Thus, the information about the lawfulness of the action largely depends on the operator’s trust in his or her superiors in the chain of command (to provide proper briefing materials and conduct target validation during the planning phase), the F-16 board computer (suggesting the appropriate time for weapon’s release) and the weapon’s guidance system (navigating the munitions to the target). At no point during our F2T2EA process will the pilot gather intelligence about the target or conduct legal analyses.

The final step is the damage assessment. In many circumstances, this battle damage assessment turns into a bomb hit assessment due to limited access and visual sight of the combat area. Immediate after action reports by the operator who conducted the strike may thus have to be supplemented by additional collection efforts to make such assessments.

Does the operator exercise meaningful human control?

Whether the operator’s actions (in this case flying the aircraft to the weapon’s envelope and ‘pickling’ when the computer indicates the appropriate time) can be considered meaningful human control has been, and continues to be, subject of international discussions. According to NGO Article 36, ‘a human simply pressing a “fire” button in response to indications from a computer, without cognitive clarity or awareness, is not sufficient to be considered “human control” in a substantive sense.’

On the one hand, it can be argued that the operator’s act of ‘pickling’ cannot be considered an informed and conscious decision or the sort of human judgment that is required under meaningful human control. On the other hand, one can also argue the contrary, because the operator’s decision to ‘pickle’ is in anticipation of a particular weapon’s effect on a known target (assuming the operator has received sufficient information to ensure the lawfulness of his/her action).

Although these types of discussions are tempting, asking whether the operator exercises meaningful human control over the weapon may be the wrong question here. Instead, we should ask how the military organization as such can or cannot ensure meaningful human control over critical targeting decisions.

Who should exercise meaningful human control and over what? The reality of distributed control

After four years of deliberations in the CCW, States are experiencing increasing pressures to produce an outcome. Yet, meaningful human control, as it is currently understood, may not be the right answer despite significant political support. The above scenario is one (of several) example(s) of a contemporary, routine mission that reveals a considerable disconnect between legal-political conceptualizations of meaningful human control and the military reality. Discussions about meaningful human control typically focus on semantics (e.g., labels) and content (e.g., elements of human control). There is much less focus on the context within which this meaningful human control ought to be exercised, more specifically, who should exercise meaningful human control and over what.

A narrow focus on the operator controlling the weapon does not pay due attention to the division of labor between humans and machines and reconfigurations of human agency as it is transposed within the decision-making process (e.g. the targeting cycle). As a result, the human role in formulating objectives, developing and approving targets, conducting collateral damage estimations and producing weaponeering solutions, making proportionality analyses, and deciding on operational constraints and restrictions is ignored because the concept of meaningful human control typically adopts a narrow focus on the phase during which the weapon is activated or used in some manner.

Although the operator’s role may seem minor in our analysis, this is not to say that it is negligible. Instead, it is to illustrate that F-16 operators are part of a larger system. This becomes particularly clear in the above deliberate targeting scenario, but the same applies to dynamic targeting where the role of the pilot in ensuring legal compliance may be very different. Thus, the key point is that even though each situation may require different forms of human control, in any case, that human control is distributed. Therefore, the use of weapons ought to be understood as only one part of the cycle and meaningful human control could be better described as distributed control that is spread across a range of individuals (and sometimes technologies) who operate in various phases of the targeting cycle.

Whereas meaningful human control theoretically assumes the existence of an ultimate decision (e.g., the trigger pull moment), military practice shows that discretion is typically distributed. Furthermore, whereas meaningful human control is typically concerned with the relationship between weapons and their operators, military practice shows a division of labor where critical decisions are made by multiple individuals at multiple junctures in the targeting process and, as I explain here, regularly do not have a direct causal relationship with weapon’s use (e.g., when targets are developed and approved at the operational level there is no consideration (yet) of the appropriate weapon, means or method).

Considering this, the concept of meaningful human control is not the only, or perhaps the most fitting, approach to analyzing (the effect of autonomous technologies on) human control over critical targeting decisions. Instead, the more appropriate analytical lens would be one that recognizes the distributed nature of control in military decision-making in order to pay due regard to a practice that has shaped operations over the past decades and continues to be standard in contemporary targeting. The concept of meaningful human control could still play an important role in determining the threshold of what is acceptable behavior and what is not. However, it can only be of value through the lens of distributed control. The stakes in this debate are high as the adoption of new regulation or a political declaration based on a misunderstanding of current targeting practices risks weakening existing law.

***

This blog is adapted from an article about meaningful human control (in progress) and is part of a broader empirical research project regarding the practice of targeting that is based on interviews and (group) conversations with over 50 practitioners, participation in courses relevant for targeting, observation-participation of military exercises and war-games, meetings and conferences regarding targeting, military operations more general, and human-machine relationships. The views expressed are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the position of any party or individual consulted in the process of this research.

***

Footnotes

[1] Both types of targeting are vitally important to achieve the campaign’s objectives. The major advantage of dynamic targeting is that it provides the opportunity to act in a responsive and timely manner to evolving situations, providing the opportunity to exploit enemy vulnerability that may be of limited duration. Deliberate targeting on the other hand takes time, making it too slow to effectively respond to dynamic targets (e.g., emerging and fleeting targets). But, concomitantly, this time can be considered a price worth paying when it comes to the realization of strategic effects. Deliberate targeting allows more rigorous analysis of information—a level of detail that is particularly relevant in the environment and conditions of contemporary operations within which collateral damage has become almost intolerable. Regardless of these differences, both types of targeting require a great deal of prior planning and coordination; and the doctrine of the deliberate targeting process controlled by strategy, objectives and guidance, the relevant law, rules of engagement, national caveats etc., is equally applicable to the dynamic process. NATO. Ajp-3.9 Allied Joint Doctrine for Joint Targeting. 2016.

[2] Little has been written about the actions of the aircrew at the wing level. Most of the above information is gathered through interviews, but more information (e.g. on what it means to ‘pickle’) can be found in Michael W. Kometer, Command in the Air – Centralized Versus Decentralized Control of Combat Airpower (Alabama: Air University Press, 2007).

***

Related blog posts

➡ Human judgment and lethal decision-making in war Paul Scharre

➡ Autonomous weapon and human control Tim McFarland

➡ Autonomous weapon systems: An ethical basis for human control? Neil Davison

➡ Autonomous weapon systems: A threat to human dignity? Ariadna Pop

➡ Ethics as a source of law: The Martens clause and autonomous weapons Rob Sparrow

➡ Autonomous weapons mini-series: Distance, weapons technology and humanity in armed conflict Alex Leveringhaus

➡ Introduction to Mini-Series: Autonomous weapon systems and ethics

See also

➡ Artificial intelligence and machine learning in armed conflict: a human-centred approach ICRC

DISCLAIMER: Posts and discussion on the Humanitarian Law & Policy blog may not be interpreted as positioning the ICRC in any way, nor does the blog’s content amount to formal policy or doctrine, unless specifically indicated.

Comments