Letter from Lebanon was filmed in 1983 [1] eight years after the civil war had broken out in the country. A sensitive and committed portrayal of the ICRC’s work, John Ash’s 30-minute film is one of the organization’s most original films from the 1980s and most accomplished documents on the Lebanese Civil War.

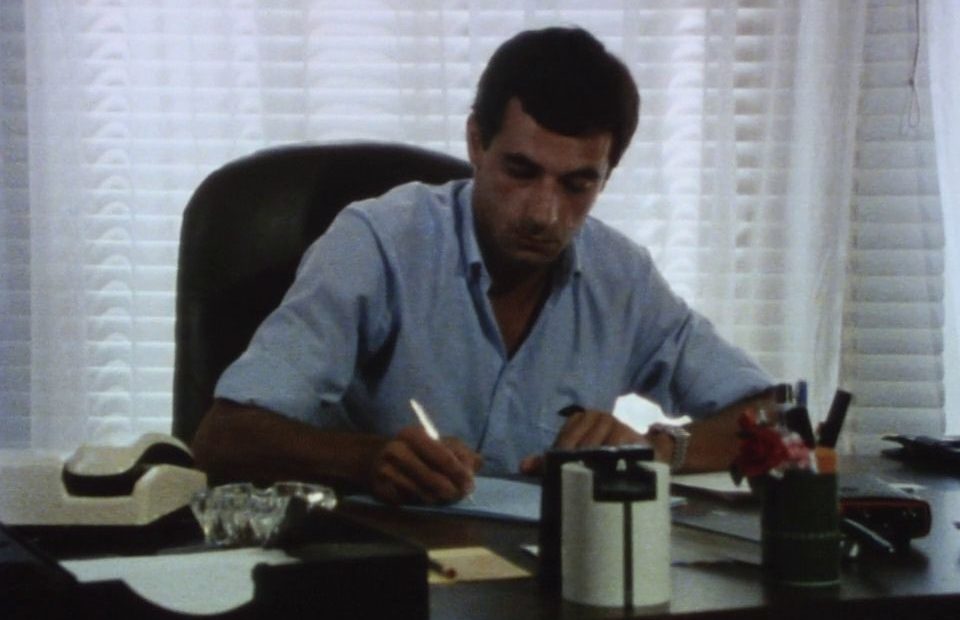

John Ash, film-maker

John Ash was recruited by the ICRC towards the end of 1983 to make a film about Lebanon.[2] It was at a time when the audiovisual activities of the organization were beginning to emerge from a period of profound change. A new unit in the Department of Information – the Division of Audiovisual Communication (DICA) – had replaced the International Red Cross Audiovisual Centre, a service which had been jointly managed by the ICRC and the League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (as it was then called) and which, at the request of the latter, had stopped its activities on 1 February 1983.[3]

The new unit, which had been set up following recommendations from an outside expert, was expected to strike the difficult balance between “future needs in the field of audiovisual communication (training, information, dissemination, etc.) and the means to be implemented to meet them”, given that the audiovisual world was undergoing extremely rapid technological change and also that the organization’s financial means were limited.[4]

John Ash, a multilingual, 36-year-old British citizen [5], had undertaken several assignments from 1976 onwards for the League in Southern Africa, Asia and the Caribbean. His wealth of varied experience and knowledge of the ICRC’s humanitarian approach suggest that he was able to meet the challenge of producing high-quality work on low budgets, in line with the requirements of the brand new DICA.

The documents held in the ICRC’s archives about Ash and the Letter from Lebanon provide little information about how the film was shot and produced. What is certain is that Ash visited Beirut twice. His first visit to the Lebanese capital was from 13 November to 3 December 1983 and he later spent another two weeks there from 4 June 1984.[6] The visit to Beirut was followed by ten days of post-production in Geneva, from 4 to 14 December 1984.

It is clear, however, that these two short filming periods only partially cover the time range during which the events reported in the film occurred. It is not possible that Ash could have personally filmed or directed the entire shoot, and this implies that he must have used existing material when editing.

Although the existence of photographs and photo shoots for the events of interest to us is mentioned in the “Information from the field” section of the 1983 Activity Report, no one is mentioned by name:

“Special news (film and photo) reporting teams also worked with the information delegate in Beirut, covering, in particular, the operations on behalf of the inhabitants of southern Lebanon, Deir al-Qamar and Tripoli and the simultaneous release of the prisoners held by the Israeli authorities and the PLO.”[7]

As we will see in the discussion below, this is precisely the subject matter of Ash’s film. We owe the footage of the liner Appia arriving in Tripoli on 17 December, or the evacuation of displaced people from Deir al-Qamar to Beirut, which took place from 15 to 22 December, to these “special news and reporting teams” and not to Ash, who we know left the country on 3 December. The group was made up of Laure Speziali[8] – head of information in Beirut – accompanied by Edouard Winiger and Bernard Robert-Charrue.[9] We also know, however, that Ash filmed the release of the prisoners held in the Israeli internment camp at Ansar, which took place during his November trip to Lebanon.

Another possible source of images is footage shot for a “Film on the West Bank (settlements) and South Lebanon”, which is mentioned in a letter from the Tel Aviv delegation to Geneva in May 1984. This was eight hours of footage focusing on daily life in the region, filmed by the Mennonites in Jerusalem and which may have been “scavenged” for possible use in an ICRC film. It is difficult to tell whether this material, for which we only have a summary description, was used by Ash or not, given that he was to return to Lebanon in June of the same year.

What is particularly worth taking away from this brief overview of how the film was shot is that Ash the film-maker was able to use a disparate set of materials to confer on his edited version a stylistic coherence and his own personal style.

It is also worth noting that the biggest gap in the documentation we have about this film is that there is no copy of the initial film treatment that Ash presented to the ICRC. It is certain that at least one copy of Ash’s treatment was circulated as it is mentioned in the appendix to a letter of 18 April 1984 sent from Geneva to Michel Amiguet in Beirut, but unfortunately no trace has been found of this copy.

Despite the dearth of other information on the making of this film, a close reading of the script and a look at how it was edited can bring to light the director’s personal contribution to the presentation of the ICRC’s activities in Lebanon in 1983, as described in his film.

The making and film genre of “Letter from Lebanon”

We can legitimately ask what were the objectives and expectations of a film like Letter from Lebanon. Obviously, the idea was to tell viewers as well as possible about what was “really” happening in the country and at the same time demonstrate the absolute need for the ICRC’s involvement. Film as a medium, through the eloquence of imagery, is a powerful tool that can be used to justify the work of the ICRC’s delegates in the field and their ability to relieve the suffering and difficulties of people in need.

However, all reporting on war and suffering is confronted with the problem of attracting and retaining the attention of the audience. The spectacle of human suffering on a global scale is as endless as the misfortune which causes it and, as such, inevitably produces viewer fatigue. We know that by dint of being intolerable, suffering becomes “invisible”, because it is unbearable and, strictly speaking, unwatchable.

In 1984, when the documentary was produced, the Lebanese people had been suffering the terrible effects of war for nine long years during which the renewed hostilities never failed to make the headlines. The subject matter was therefore far from new which meant that if the message that needed to be put across was going to capture the attention of audiences turned off by the length of the conflict, it had to be conveyed in an original and punchy work.

Letter from Lebanon: Martyrs’ Square in Beirut (© CICR / ASH, John / 1984 / V-F-CR-H-00165) : 00:03:09

In the specific case of ICRC productions, in addition to the problem of viewer fatigue, another constraint had to be considered, one which hampered a personal approach to subject matter and created an extra difficulty. This was that the various bodies and activities of the ICRC, from the Central Tracing Agency to Red Cross messages, restoring family links, medical care or prisoner visits, make up a closed group of topics which have necessarily to be repeated throughout reports, across countries and over the years. They have become a sort of “litany” of the ICRC’s humanitarian action, whose variations and themes would be fascinating to trace in our collections – but that is for another time.

In developing Letter from Lebanon, the main challenge for John Ash – and all the more so since he had only recently been hired, had to prove his worth to the ICRC and had to show that the DICA was getting off to a good start – was to use his experience and talent as a director to make viewers receptive again to the subject matter, i.e. not only a never-ending civil and international war, but also the ICRC’s operational activities, which had been filmed over and over again in the past.

There is no doubt, however, that the solutions Ash found were both ingenious and coherent, and demonstrate his confident mastery of the language of film. This can be seen not only in the script, the editing and how he presents the different ICRC activities, and portrays the various protagonists, but also in how he uses the soundtrack. The rest of this article will take a closer look at these different aspects.

[1] Among the plethora of documents available on the action of the ICRC and the Lebanese Red Cross since the beginning of the war, see, for example, “ICRC and Lebanese Red Cross action in Lebanon, 1975–2015”, available at: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/lebanon-icrc-and-lebanese-red-cross-action-during-periods-war-lebanon-1975-2015#gs.kfv2jr, accessed 12 December 2019.

[2] This article is based in part on sources that are not yet publicly available. We have only used general information and only when this has direct relevance to the making of Letter from Lebanon. After a temporary assignment at the end of 1983, John Ash worked for the ICRC for about one year from 1 February 1984. Before leaving the organization, Ash made another film of a little under 30 minutes: A Message from Aaland. With Stockholm, the Finnish island of Aaland hosted the Second World Conference on Peace of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, held from 2 to 7 September 1984.

[3] ICRC, Annual Report 1983, Geneva, 1984, p. 106.

[4] The detailed report on the DICA’s audiovisual activities in 1983 for the ICRC, the National Societies and the League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies indicates that “the ICRC endeavoured, for the first time, to make a film and photo summary of its principal activities of 1982.” This documentary film, entitled “1982 in retrospect”, is a video montage of film clips and photos retracing the main events of 1982 as experienced by the ICRC in Geneva and in the field. This is the birth of the ICRC “Panorama” genre.

[5] He speaks the main European languages plus some spoken in India and the Philippines (Hindi, Gondi and Tagalog).

[6] Two Mission Approval forms have been kept from Ash’s visits to Beirut: one for “preparing an ‘info’ brochure on Lebanon”, dated 11 November 1983; the other, dated 4 November 1983, to “prepare Lebanon film” from 13 to 28 November 1983. Bruno Hubschmid, an ICRC photographer, arrived in Beirut at the same time as Ash; later, on 21 November, Pio Corradi and Bernard Robert-Charrue, an ICRC cameraman and sound recordist respectively, arrived in Beirut, but they only stayed for two days; on 16 November, it was a Swiss TV (TSR) crew who left. John Ash’s departure from Lebanon on 3 December 1983 was confirmed by the delegation in Beirut.

[7] ICRC, Annual Report 1983, Geneva, 1984, p. 104.

[8] After serving as ICRC delegate in Poland and Lebanon and taking part in the launch of Radio Cité in Geneva, Speziali was hired by the TSR at the end of 1985, where she is still working today. Cf. Ma RTS, available at: https://pages.rts.ch/emissions/religion/dieu-sait-quoi/emission/1756679-laure-speziali.html, accessed on 12 December 2019.

[9] We know that the information delegate went to Tripoli on 17 December with the ICRC film team – Edouard Winiger and Bernard Robert-Charrue – to follow the evacuation of the wounded Palestinians. From 18 to 22 December she went to Deir al-Qamar with the same crew. Edouard Winiger and Bernard Robert-Charrue arrived in Beirut via Tel Aviv on 15 December and left on 24 December.

Comments