« All persons (…) shall be enabled to give news of a strictly personal nature to members of their families, wherever they may be, and to receive news from them. » (Article 25, IV Geneva Convention of 1949)

Table of contents

The Legal Framework of the Central Tracing Agency

Initially, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was founded in 1863 with the mission to improve the care and protection of sick and injured soldiers in war. From 1870 onwards, it also began operating tracing agencies in wartime to assist persons deprived of their liberty, displaced and/or separated from their families. The different agencies of the late 19th and 20th century paved the way for the ICRC’s present-day Central Tracing Agency (CTA). For the past 150 years, these agencies have helped mitigate the humanitarian consequences of wartime captivity. They’ve traced the missing, identified the dead, informed families, and reunited those separated by conflict, violence or migration.

First of its kind, l’Agence de Bâle (‘the Basel Agency’), was founded on July 18, 1870 – a mere three days after the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War. During the conflict, it served as an information and relief bureau for prisoners of war (POWs). The ICRC then re-opened an agency for each major conflict of the first half of the 20th century. The core of their mandate remained similar: offering protection and relief to POWs, later including also civilian internees and displaced populations. During WWI and WWII, for example, the Agency [1] recorded the movements of detainees, investigated the fate of the missing, distributed correspondence and relief packages to detention camps, and arranged for the repatriation, emigration or reunion of separated family members.

To fulfil this mandate, the Agency captured as much information as possible on the fate of war victims. Over the years, this meticulous work produced millions of index cards, which retrace the journeys of millions of individuals whose lives have been uprooted by conflicts. By recording the fate of prisoners, internees or displaced persons and communicating it to their relatives, the ICRC’s tracing agency provides a first level of protection against ill-treatments and enforced disappearances. And when traditional means of communication are suspended in wartime, it remains the one avenue left open to those separated by frontlines.

Developed by the ICRC Library, this research guide introduces a collection of publications on the Agency that have been digitized to celebrate its 150th anniversary in 2020. Dating back to 1870, they document the history of its humanitarian action and communication efforts. The guide is divided in three parts. The first presents the Agency’s mandate in international humanitarian law. The second introduces the publications documenting four key eras of its history: the Basel Agency (1870-1871), the International Prisoners of War Agency (1914-1923), the Central Prisoner of War Agency (1939 – 1960) and the Central Tracing Agency (1960 to the present). Finally, it ends with a selected bibliography presenting works by historians, legal scholars and humanitarian actors on the Agency, and recent scholarship on related issues. For any questions or suggestions regarding the research guide’s content, contact us at library@icrc.org.

The ICRC’s Tracing Archives

What happens to the files created by the Agency during conflicts, the millions of index cards that document the capture, transfer or death of an individual? The Agency’s files from past conflicts are under the responsibility of a dedicated service of the ICRC. It continues to respond, sometimes decades after the end of a conflict, to requests for information sent by its victims and their descendants. The archival collections under its care also comprise the individual records of beneficiaries, sources of information collected by the Agency such as lists of prisoners and death certificates, and the correspondence, records and administrative archives of the different Agencies.

Geneva, International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. The archives of the International Prisoners of War Agency created during the First World War (ICRC/Ian Alderman)

The exceptional nature of these archives was recognized by UNESCO in 2007, which included the archives of the International Prisoners of War Agency (1914-1923) in its Memory of the World Register. Fully digitized, the Agency’s WWI archives can be viewed online on the ICRC’s Grande Guerre website and are on display at the International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent in Geneva.

To find out more about the ICRC’s Tracing Archives

The Legal Framework of the Central Tracing Agency

A mandate based on humanitarian experience and enshrined in international humanitarian law

Necessity being the mother of invention, the Agency’s action has almost systematically anticipated the development of the law. No provisions of international law related to the creation of an information and relief agency were included in the Geneva Conventions adopted in 1864 and 1906, which grounded the ICRC’s action in wartime. Thus, the consecutive creation of the Basel Agency (1870-1871), the Belgrade Agency (1912-1913) and the International Prisoners of War Agency (1914-1923) had no specific international legal basis. These first Agencies could nevertheless rely on the resolutions of the International Conferences of the Red Cross and Red Crescent and on the collaboration of the National Societies of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. A year before the foundation of the Basel Agency, delegates to the 2nd International Conference of the Red Cross had indeed adopted a resolution which gave the ICRC a new responsibility in wartime: overseeing a bureau dedicated to the transmission of information and correspondence. [3]

The Agency’s role was codified in international law for the first time with the adoption of the Convention relative to the treatment of prisoners of war in 1929. Article 79 of the Convention provided that, “a Central Agency of information regarding prisoners of war shall be established in a neutral country. The International Red Cross Committee shall, if they consider it necessary, propose to the Powers concerned the organization of such an agency. This agency shall be charged with the duty of collecting all information regarding prisoners which they may be able to obtain through official or private channels, and the agency shall transmit the information as rapidly as possible to the prisoners’ own country or the Power in whose service they have been.” The adoption of this article in 1929 clearly stemmed from the considerable role played by the Agency during WWI and gave its potential successors a solid basis for action. This was an important development, as the Agency’s work depended on the cooperation of the belligerents, the most important sources of information on the fate of detainees and war victims.

Because it only planned for the Agency to collect information on POWs in situations of international conflicts, this first legal basis proved insufficient very quickly. In 1936, the Agency got involved helping the victims of the Spanish Civil War, a context in which its action – precisely because it was an internal conflict – had no legal basis. [4] Then, from 1939 on, WWII led to a massive expansion of the Agency’s action to trace and reunite displaced, interned or missing civilians, in addition to its action for POWs. In fact, by creating a service dedicated to tracing missing civilians, the Agency had already during WWI gone above and beyond the framework laid down by the drafters of the 1929 Convention. The law caught up in 1949 with the adoption of the Convention (IV) relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war. As the protection of civilians was finally included in the provisions of international humanitarian law (IHL), the legal basis of the Agency’s mission was developed accordingly. The revised Geneva Conventions adopted in 1949 provided for the organization of central information agencies for POWs and for civilians in international conflicts.

Like in 1929, the Geneva Conventions adopted in 1949 do not automatically allocate the responsibility of managing these agencies to the ICRC. The Committee must be free to offer its services, but the Conventions give belligerents the option to agree on a different option, provided that the agencies are set up as specified. In practice, the agencies founding their action on the 1949 Geneva Conventions have systematically operated under the aegis of the ICRC and assumed the role of information bureaux for both detainees and civilians. This is reflected in the language of the 1977 Protocol Additional to the Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 relating to the protection of victims of international armed conflict (Protocol I), as article 33 refers specifically to the ‘Central Tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross’. Protocol II on the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts, on the other hand, does not contain any provision relative to the Agency. [5] The CTA thus continues to rely on the ICRC’s right of initiative in internal conflicts, which have represented a growing part of its operational contexts since the end of WWII. The ICRC’s right of initiative is recognized in the common article 3 of the Geneva Conventions and is included in the statutes of the International Red Cross.

Dispositions of current IHL treaties relative to the Central Tracing Agency

Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. Geneva, 12 August 1949

Art. 16 : Recording and forwarding of information (commentary of 2016)

[extract] « Parties to the conflict shall record as soon as possible, in respect of each wounded, sick or dead person of the adverse Party falling into their hands, any particulars which may assist in his identification. »

Art. 17 : Prescriptions regarding the dead. Graves Registration Service (commentary of 2016)

[extract] « Parties to the conflict shall ensure that burial or cremation of the dead, carried out individually as far as circumstances permit, is preceded by a careful examination, if possible by a medical examination, of the bodies, with a view to confirming death, establishing identity and enabling a report to be made. »

Convention (II) for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea. Geneva, 12 August 1949

Art. 19 : Recording and forwarding of information (commentary of 2017)

Art. 20 : Prescriptions regarding the dead (commentary of 2017)

Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949

Art. 17 : Questioning of prisoners (commentary of 2020)

Art. 30 : Medical attention (commentary of 2020)

Art. 68 : Claims for compensation (commentary of 2020)

Art. 70 : Capture card (commentary of 2020)

[extract] « Immediately upon capture, or not more than one week after arrival at a camp, (…) every prisoner of war shall be enabled to write direct to his family, on the one hand, and to the Central Prisoners of War Agency (…) , on the other hand, a card similar, if possible, to the model annexed to the present Convention, informing his relatives of his capture, address and state of health. »

Art. 71 : Correspondence (commentary of 2020)

Art. 74 : Exemption from postal and transport charges (commentary of 2020)

Art. 75 : Special means of transport (commentary of 2020)

Art. 77 : Preparation, execution and transmission of legal documents (commentary of 2020)

Art. 119 : Details of repatriation procedure (commentary of 2020)

Art. 120 : Prescriptions regarding the dead, including wills and death certificates (commentary of 2020)

Art. 122 : National information bureaux (commentary of 2020)

Art. 123 : Central Tracing Agency (commentary of 2020)

« A Central Prisoners of War Information Agency shall be created in a neutral country. The International Committee of the Red Cross shall, if it deems necessary, propose to the Powers concerned the organization of such an Agency. The function of the Agency shall be to collect all the information it may obtain through official or private channels respecting prisoners of war, and to transmit it as rapidly as possible to the country of origin of the prisoners of war or to the Power on which they depend. It shall receive from the Parties to the conflict all facilities for effecting such transmissions. The High Contracting Parties, and in particular those whose nationals benefit by the services of the Central Agency, are requested to give the said Agency the financial aid it may require. The foregoing provisions shall in no way be interpreted as restricting the humanitarian activities of the International Committee of the Red Cross, or of the relief Societies provided for in Article 125 ».

Art. 124 : Exemption from charges (commentary of 2020)

Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949

Art. 24 : Measures relating to child welfare (commentary of 1958)

Art. 25 : Family news (commentary of 1958)

Art. 26 : Dispersed families (commentary of 1958)

Art. 91 : Medical attention (commentary of 1958)

Art. 106 : Internment card (commentary of 1958)

Art. 107 : Correspondence (commentary of 1958)

Art. 110 : Relief shipments III. Exemption from postal and transport charges (commentary of 1958)

Art. 111 : Special means of transport (commentary of 1958)

Art. 113 : Execution and transmission of legal documents (commentary of 1958)

Art. 129 : Wills. Death certificates (commentary of 1958)

Art. 130 : Burial. Cremation (commentary of 1958)

Art. 136 : National bureaux (commentary of 1958)

Art. 137 : Transmission of information (commentary of 1958)

Art. 138 : Particulars required (commentary of 1958)

Art. 139 : Forwarding of personal valuables (commentary of 1958)

Art. 140 : Central Agency (commentary of 1958)

« A Central Information Agency for protected persons, in particular for internees, shall be created in a neutral country. The International Committee of the Red Cross shall, if it deems necessary, propose to the Powers concerned the organization of such an Agency, which may be the same as that provided for in Article 123 of the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of August 12, 1949. The function of the Agency shall be to collect all information of the type set forth in Article 136 which it may obtain through official or private channels and to transmit it as rapidly as possible to the countries of origin or of residence of the persons concerned, except in cases where such transmissions might be detrimental to the persons whom the said information concerns, or to their relatives. It shall receive from the Parties to the conflict all reasonable facilities for effecting such transmissions. The High Contracting Parties, and in particular those whose nationals benefit by the services of the Central Agency, are requested to give the said Agency the financial aid it may require. The foregoing provisions shall in no way be interpreted as restricting the humanitarian activities of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the relief Societies described in Article 142. »

Art. 141 : Exemption from charges (commentary of 1958)

Art. 142 : Relief societies and other organizations (commentary of 1958)

Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977

Art. 32 : Section III – Missing and dead persons. General principle (commentary of 1987)

« In the implementation of this Section, the activities of the High Contracting Parties, of the Parties to the conflict and of the international humanitarian organizations mentioned in the Conventions and in this Protocol shall be prompted mainly by the right of families to know the fate of their relatives. »

Art. 33 : Missing persons (commentary of 1987)

Art. 78 : Evacuation of children (commentary of 1987)

The Agency’s Publications, from 1870 to today

Here are retraced the main stages of the historical development of the Agency through a selection of its publications, as collected, preserved and made available by the ICRC Library. Unable to cover all the conflicts in which the Agency has been active, [6] the research guide focuses on four key contexts that represented important milestones of its history: the Franco-Prussian conflict (1870-1871), WWI, WWII, and finally the development of the Agency as a permanent department of the ICRC after WWII.

Depending on their context and target audience, the Agency’s publications have quite logically taken different forms. The collection introduced here includes periodicals and brochures written for the general public – with an aim to inform, raise awareness and/or fundraise for the Agency. The reader will also find activity reports covering a specific conflict or chronological period, often produced to be presented at an International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. Finally, the Agency has also published guides and manuals to share its expertise, notably with National Societies of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

Photographs, films, videos and sound recordings on the Agency available online

The ICRC audiovisual archives hold tens of thousands of documents retracing the ICRC’s activities from the end of the 19th century to the present day – among them, many photos, films, videos and sound recordings documenting the work of the Agency. The vast majority of these invaluable archives, either digitized or digital materials, are available online via the ICRC audiovisual archives portal.

The Basel Agency (1870 – 1871)

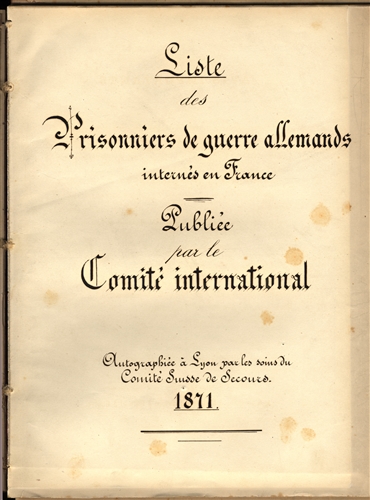

Franco-Prussian War, 1870-1871. List of German prisoners of war interned in France.

The ICRC founded its first Agency during the war fought between France and a coalition of German states led by Prussia between 1870 and 1871. Originally, the purpose of the Agency was to facilitate the distribution of communications and relief between the ‘Central Committees’ (the National Societies) of the various belligerent states. The ICRC suggested that the Agency help prisoners of war exchange letters with their families as well. From August 1870, when postal communications were interrupted, the Agency started to distribute two to three hundred letters daily. [7] It also took care of the transmission of the lists of names of injured prisoners between the belligerent states.

The Agency opened a service dedicated to answering queries on the fate of missing soldiers coming from concerned family members. As requests kept pouring in, the ICRC decided to publish and distribute the lists of injured POWs it received [8], so that families would be able to access the information directly.

Read the reports of the Basel Agency online [in French]

The International Prisoners of War Agency (1914-1923)

WWI represented a turning point in the history of the Agency. The ICRC first announced the opening of the International Prisoners of War Agency (in French, ‘Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre’, abbreviated AIPG) on August 15, 1914, in an official circular. Twelve days later, a second circular sent out to the National Societies of the Movement explained how it would operate. The AIPG was to act as an intermediary between the information offices established by the belligerents. With the help of the network formed by the National Societies, it would collect the lists of the names of captured soldiers and forward the information to their family and/or hometown.

Photographs of the International Prisoners of War Agency (ICRC audiovisual archives, see footnote for the references)

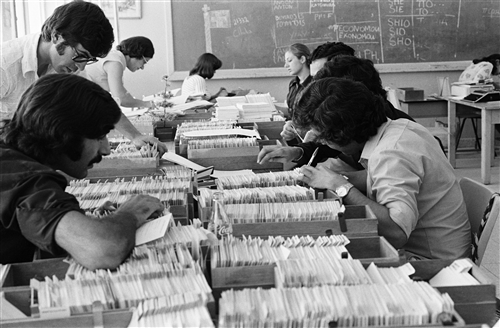

By the fall of 1914, the AIPG had grown tremendously. It had been forced to scale up its activities dramatically to keep up with the evolution of the conflict and the amount of information, letters and tracing requests it received. It hired up to 1,200 collaborators, including many volunteers, and divided work precisely among them. Every piece of information and every request received were transcribed on individual index cards. The cards were then filed according to the person’s nationality. When a card holding a piece of information met a research query related to the same individual, the Agency could forward the information to the requester. At the end of the war, the AIPG’s file comprised about 5 million index cards. They have been digitized and, along with other documents on WWI captivity (testimonies, POWs camps visit reports, postcards, etc.) can be consulted on the ICRC’s Grande Guerre platform. The AIPG also took charge of the distribution of correspondence, relief parcels and money to POW camps. A specific service was founded to answer search queries on the fate of missing civilians.

The AIPG communicated quite extensively during the war, in a way that served its humanitarian mission. Publishing a journal like the Nouvelles de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre, for example, was a practical way to reach out and make the information of public interest it collected on prisoners of war available to all. After visiting POWs camps, the ICRC delegates described the conditions of detention in reports which the International Committee also decided to publish. Sharing these reports publically prevented the belligerents from using them as propaganda and provided the public with a non-partisan source of information on the fate of POWs. [9] The AIPG’s public communication also served to raise awareness and support fundraising for its humanitarian action. It used for example to sell copies (50 cent a piece) of Le cœur de l’Europe : une visite à la Croix-Rouge internationale de Genève (‘The heart of Europe: a visit to the International Red Cross in Geneva), the story of a visit to the AIPG told by Stefan Zweig.

Journals and Visit Reports

Nouvelles de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre [in French]

Bulletin international des sociétés de la Croix-Rouge [in French]

POW camps visit reports during WWI [in French]

The mission and work of the Agency, as related by its collaborators and visitors

L’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève / by Frédéric Barbey (1915) [in French]

Organisation et fonctionnement de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève : 1914 et 1915 / Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (1915) [in French]

Renseignements complémentaires sur l’activité de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève en 1915 et 1916 / Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (1916) [in French]

Disparus et prisonniers : l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève / H.-E. Clouzot (1916) [in French]

Le cœur de l’Europe : une visite à la Croix-Rouge internationale de Genève / Stefan Zweig (1918) [in French]

Rapport général du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge sur son activité de 1912 à 1920 (1921) [in French]

Actes du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre 1914 – 1918 (1918) [in French]

The Agency’s First Manual : Organisation d’un bureau central de renseignements / Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer (1932) [in French]

“An absolute principle of the [International Prisoners of War Agency] was that no letter arriving at the Agency should ever remain unanswered and that the response ought to be as detailed as possible”.

Research Guide on the ICRC during WWI

Published primary sources & secondary literature on the AIPG in the ICRC Library’s collections

The Central Prisoners of War Agency (1939 – 1960)

The Central Prisoners of War Agency (in French ‘Agence centrale des prisonniers de guerre’ – abbreviated ACPG) was officially founded in September 1939, after the invasion of Poland. Prepared to the imminence of war, the ICRC had appointed a year earlier a commission to study how to resume the activity of its Agency. The ACPG’s mission during the conflict remained in line with that of its predecessors. In charge of centralizing all information on prisoners of war and civilian internees, the ACPG acted as a neutral intermediary for the communication of this information between the belligerents. Its collaborators investigated the fate of the missing on behalf of their families. They organized the distribution of correspondence, donations of money and relief packages to the camps.

Photographs of the Central Prisoners of War Agency (ICRC audiovisual archives, see footnote for the references)

If the mission remained the same, the ACPG benefitted from advances in technology to fulfil its mandate with increased efficiency compared to its predecessors. The use of photocopiers, microfilms, radio broadcasting and telegraphy allowed it to expand its activities to match the unprecedented dimensions of the global conflict. Regimental enquiries were conducted on a much larger scale that in WWI, thanks to the use of statistical machines. [10]

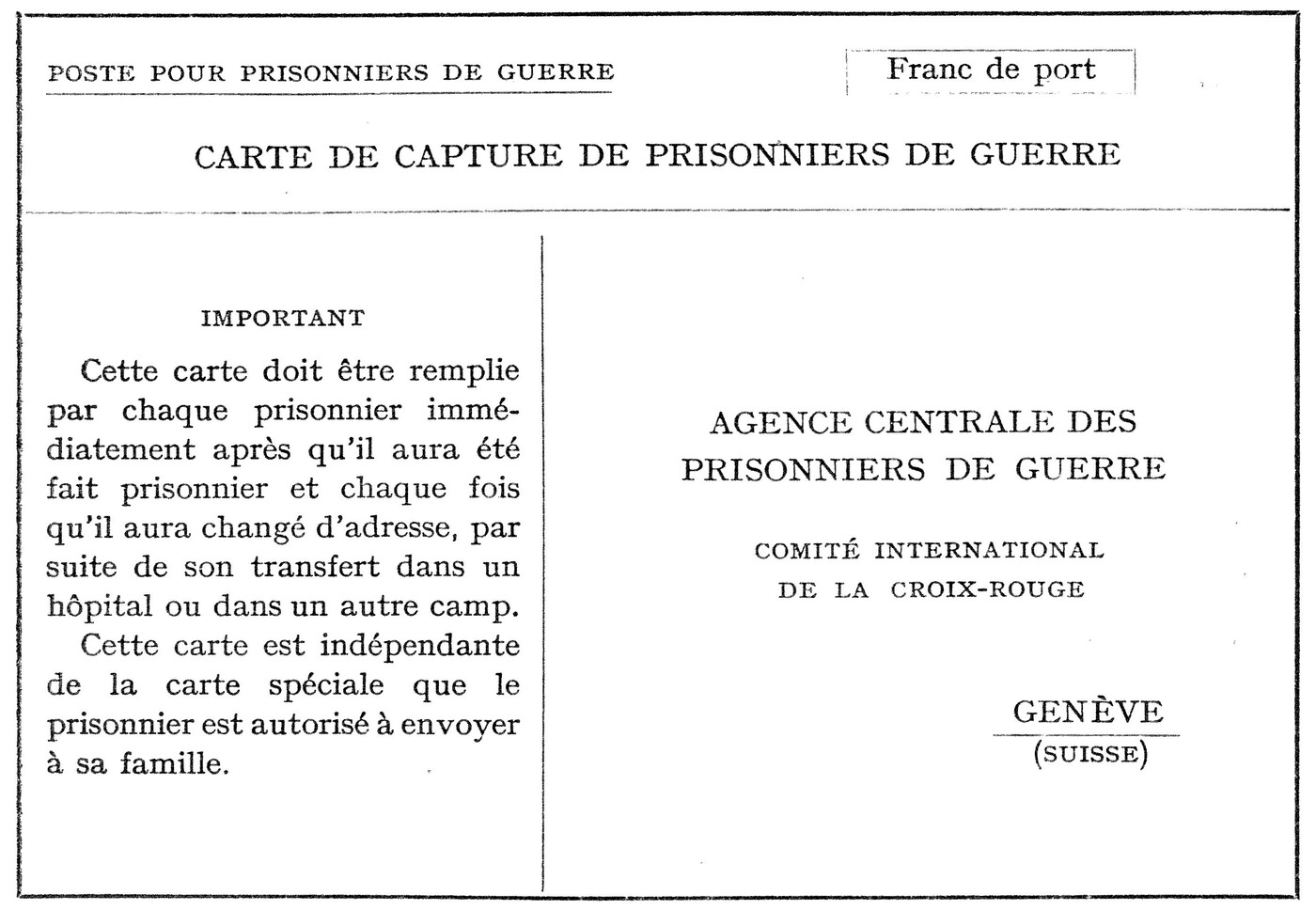

The ACPG also influenced how the information that its work depended on was produced and transmitted. The ICRC’s delegate in Berlin developed a new system to record POWs: the capture card, a certificate of captivity filled by the prisoner himself directly upon arrival at a POW camp. Because the capture cards were sent to the ACPG directly, its collaborators could record and process the information much faster than before. They no longer had to wait for the belligerents to send out their official lists of prisoners.

Capture card addressed to the Central Prisoners of War Agency (ICRC Archives)

The ACPG also created forms specifically designed to receive family news, so that their distribution would not be slowed down by censorship. WWII was characterized by the development of the Agency’s action in favor of civilians. In June 1947, the ACPG’s file contained nearly 36 million index cards, of which 6 to 7 million solely concerning civilians. [11]

The ACPG did not close its doors at the end of the war. At first, it was kept busy with the repatriation of former POWs and the reunion of separated families. It was also soon tasked with providing former prisoners with certificates of captivity or of hospital admission. In fact, the ACPG never truly stopped its activities after WWII ended. It is true that the 1949 Conventions still provided for the creation of ad hoc agencies during each conflict. But, concerned both with the humanitarian fallout from WWII and the emergence of new conflicts, the ACPG soon morphed into a permanent department of the ICRC. On July 1, 1960, it was renamed ‘Central Tracing Agency’ (CTA) to reflect the evolution of its mandate.

Les Nouvelles de l’Agence centrale des prisonniers de guerre

The circulation of the ‘Nouvelles de l’Agence’ (Agency News) had been an important part of the ICRC’s diligent public communication strategy during WWI. When the Agency re-opened in the early days of WWII, the publication of the Nouvelles resumed. But they now served the Agency’s internal communication. The first issues were stamped with the mention ‘confidential’. After 1941, a heading specified that “the news [were] restricted to the Agency’s personnel”. Digitized, the whole collection of the Nouvelles is now available to all online.

Journals and articles

Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, see the issues published during the ACPG’s years of activity [in French]

The mission and work of the Agency, as related by its collaborators and the ICRC

Work of the International Red Cross Committee and of the Central Agency for prisoners of war since the outbreak of war / International Committee of the Red Cross (1942) – also available in French.

L’action du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre : 1939-1945 / Jacques Chenevière (1946) [in French]

Le service médical de l’Agence des prisonniers de guerre du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge / Alec Cramer (1946) [in French]

Les sections auxiliaires du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge / Marguerite Van Berchem (1947) [in French]

Activity reports

Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities during the Second World War (September 1, 1939 – June 30, 1947), Vol. II – also available in French and in Spanish.

Summary report of the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross (1st July 1947 – 31st December 1951) – also available in French, Spanish and German.

For more information on the Agency during WWII

Research guide on the ICRC during WWII

Published primary sources and secondary literature on the ACPG in the ICRC Library’s collections

The Central Tracing Agency (1960 to the present day)

With the constant eruption of new conflicts in the post-WWII period, the Agency became involved in one new context after the other: Palestine in 1948, then the Algerian War (1954-1962), the Vietnam War and the wars of national liberation on the African continent in the 1960s, the conflicts in Cyprus (1964 and 1974), the Arab-Israeli Wars (1967-1973), the Jordanian Civil War (1970-1971), the Indo-Pakistani War (1971), the Falklands War (1982), the Gulf War (1990-1991), among others. Non-international conflicts grew to represent a significant portion of the Agency’s operational contexts during the same period.

The ICRC’s action to restore family links illustrated (ICRC audiovisual archives, see footnote for the references)

At the same time as it became a permanent department of the ICRC, the Agency decentralized part of its activities to work in close proximity with affected populations. Created within ICRC delegations in conflict zones, local offices of the CTA are responsible for processing tracing requests, transmitting family messages, preparing the reunification of separated family members, and issuing travel documents. The Agency continues to work on behalf of detainees, but it has scaled up its activities for civilian populations, to respond to the humanitarian consequences of armed conflicts, other situations of violence, disasters and migration. Its current strategy still relies on a close collaboration with the National Societies of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Together they form the global Restoring Family Links Network. The Agency and the Protection Division of the ICRC have also developed an expertise in forensic science, which they use to support authorities in identifying the deceased. [12]

Last major evolution worth highlighting here, the rise of new information and communication technologies is revolutionizing the Agency’s possibilities in terms of information management. [13] They also create new risks to watch out for, notably in terms of data protection. [14] The Agency provides online tracing services through the Restoring Family Links platform, managed in collaboration with the National Societies of the Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. In 2019, the collaborators of the CTA and the Protection Division of the ICRC distributed 141,590 family messages, allowed more than 13,000 detainees to receive visits from their families and were able to inform the families of 9,503 missing individuals about the fate of their relative. [15]

ICRC Protection Policy

The Agency’s work is an important part of the ICRC’s activities for the protection of populations affected by armed conflicts and other violence. Protection is one of the four main components of the organization’s humanitarian action, which also include prevention, assistance and cooperation. Adopted in 2008, the protection policy outlines the principles of the ICRC’s protection framework, as well as the operational guidelines based on that framework. For more information on ICRC policy documents (texts validated by the Assembly to guarantee the coherence, integrity and sustainability of the ICRC’s action), go to our dedicated research guide.

Presenting the Central Tracing Agency : selected publications

Central Tracing Agency of the ICRC / ICRC (1985) – also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, German.

The International Prisoners-of-War Agency : the ICRC in World War One / ICRC, International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (2007) – also available in French.

Restoring family links strategy : including legal references (2009) – also available in French, Spanish, Arabic, Russian, Chinese.

Restoring family links : presenting the strategy for a worldwide network (2009) – also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese.

Protecting people deprived of their liberty (2016) – also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Russian.

The need to know : restoring links between dispersed family members (2018) – also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Russian, Chinese.

Missing persons project: working together to address a global human tragedy / CICR (2018).

Restoring links between dispersed family members / CICR (2019) – also available in French, Spanish, Chinese, Portuguese, Russian, Arabic.

Restoring family links : families belong together / CICR (2019) – also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic.

How to set up a tracing service [1970] – also available in French and Spanish.

Guide for National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (1988) – also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Arabic, Russian).

Guidelines for tracing in disasters / in collaboration with the League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (1989) – also available in French, Spanish and Arabic).

Central Tracing Agency : advice for the tracing services of national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies : the computer as a tool for a card index or a name file : users’ guide (1994) – also available in French).

Central Tracing Agency : advice to the tracing services of the National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies : electronic communication of personal data (1996) – also available in French.

Restoring family links : a guide for National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (2000) – also available in French, Spanish and Arabic.

Management of dead bodies after disasters : a field manual for first responders / Morris Tidball-Binz et al. (2nd ed., 2016) – also available in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Russian and Chinese.

Accompanying the families of missing persons : a practical handbook (2015) – also available in French.

Professional standards for protection work : carried out by humanitarian and human rights actors in armed conflict and other situations of violence / ICRC, in collaboration with an advisory group made up of collaborators from different organizations and NGOs (2018) – also available in French, Spanish and Arabic.

Selected Bibliography

Reference Works

The Central Tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross: activities of the ICRC for the alleviation of the mental suffering of war victims / Gradimir Djurovic. Genève: Henry Dunant Institute, 1986 – also available in French.

A vast and detailed study of the Central Tracing Agency, from its early days to the 1970s, written by one of its former collaborators.

The International Committee of the Red Cross and the protection of war victims / François Bugnion. 2e ed., Genève : CICR, 2000 (1994) – also available in French, Chinese and Russian.

The Agency in the conflicts of the 19th and 20th centuries

La Croix-Rouge et les prisonniers de guerre : l’émergence d’une préoccupation (1863 – 1912) / Bernard Mercier. Genève : B. Mercier, 1991.

(S’)aider pour survivre : action humanitaire et neutralité suisse pendant la Première Guerre mondiale / Cédric Cotter. Chêne-Bourg : Georg, 2017.

Action humanitaire et quête de la paix : le prix Nobel de la paix décerné au CICR pendant la Grande Guerre / études réunies par Valérie Lathion, Roger Durand, François Bugnion, Françoise Dubosson, Irène Herrmann et Daniel Palmieri. Genève : Fondation Gustave Ador ; Georg, 2019.

Romain Rolland et l’Agence des prisonniers de Genève (1914-1916) / Claire Basquin. Paris : s.n., 1999. Thèse pour le diplôme d’archiviste paléographe, Ecole nationale des Chartes, Paris.

La Grande Guerre 1914-18, un nouveau défi pour le CICR ? : l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre et son action en faveur des civils / Jessica Pillonel. Mémoire de master, Université de Genève, 2012.

Le CICR, le Vatican et l’œuvre de renseignements sur les prisonniers de guerre : rivalité ou collaboration dans le dévouement ? / Delphine Debons, Relations internationales, no 138, 2009.

Les enfants grecs déplacés et l’Agence centrale des prisonniers de guerre / E.L. Jaquet, Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no., 378, 1950.

Coopération entre l’Agence centrale de recherches du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge et les Services de recherches des Sociétés nationales de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge / Nicolas Vecsey. Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no. 771, 1988.

La coopération du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge avec les services de recherches des Sociétés nationales dans les états nouvellement indépendants de l’ex-URSS / Violène Dogny. Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no. 830, 1998.

L’action de l’Agence centrale de recherches du CICR dans les Balkans durant la crise des réfugiés kosovars / Thierry Schreyer. Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no. 837, 2000.

Reuniting children separated from their families after the Rwandan crisis of 1994: the relative value of a centralized database / Maarten Merkelbach. International Review of the Red Cross, vol. 82, no. 838, 2000.

The International Committee of the Red Cross: identifying the dead and tracing missing persons, a historical perspective / Isabelle Vonèche Cardia. Chapter in Violence, statistics and the politics of accounting for the dead, Cham [etc.]: Springer, 2016.

Contemporary humanitarian issues

Assistance to displaced populations and families separated by conflict

New technologies and new policies: the ICRC’s evolving approach to working with separated families / Olivier Dubois, Katharine Marshall, and Siobhan Sparkes McNamara. International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 94, no. 888, 2012.

Missing persons: multidisciplinary perspectives on the disappeared / ed. by Derek Congram. Toronto: Canadian scholars’ press, 2016.

International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 99, no 905, 2017. Special edition “The missing”.

Missing migrants and their families: the ICRC’s recommendations to policy-makers / ICRC. Geneva: ICRC, 2017.

Clarifying the fate and whereabouts of missing migrants: exchanging information along migratory routes: report on the workshop: 15-16 May 2019, Antigua, Guatemala / written by Gabriella Citroni and commissioned by the Missing Persons Project of the ICRC, Geneva: ICRC, 2019.

The search for missing persons, including victims of enforced disappearances: report on the international expert working meeting: 3-4 September 2019, Jordan / written by Gabriella Citroni and commissioned by the Missing Persons Project of the ICRC, Geneva: ICRC, 2020.

Supporting and strengthening work with relatives of missing persons: report on the workshop: 2-3 July 2019, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina / written by Shari Eppel and commissioned by the Missing Persons Project of the ICRC, Geneva: ICRC, 2020.

Displacement in times of armed conflict: how international humanitarian law protects in war, and why it matters / Cédric Cotter. Geneva : ICRC, 2019 – also available in French, Spanish, Arabic.

Humanitarian Forensic Action

Violence, statistics, and the politics of accounting for the dead / ed. by Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, Elizabeth Minor and Samrat Sinha. Cham [etc.]: Springer, 2016.

The ICRC AM/PM database: challenges in forensic data management in the humanitarian sphere / Ute Hofmeister. Forensic Science International, Vol. 275, 2017.

International humanitarian law: the legal framework for humanitarian forensic action / Gloria Gaggioli. Forensic Science International, Vol. 282, 2018.

Forensic science and humanitarian action: interacting with the dead and the living / Sara C. Zapico, Douglas H. Uberlaker, Roberto C. Parra, 2020.

Further readings: all the documentation available in the ICRC Library collections on the Agency

[1] The use of the term “Agency” is understood here, as in the rest of the research guide, in a generic sense, replacing the phrase “the successive tracing agencies of the ICRC”. Specific agencies will later be referred to with their own abbreviation, such as ‘CTA’ for the contemporary Agency, the Central Tracing Agency.

[2] See also the rules governing access to the archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, adopted by the ICRC Assembly on 2 March 2017.

[3] « In wartime, the International Committee will make sure that a correspondence and information bureau is formed in a suitable location, which will facilitate the communication between the committees and the transmission of relief in every way possible ». (source) Extract translated from French, included in Compte rendu des travaux de la Conférence internationale tenue à Berlin du 22 au 27 avril 1869 par les délégués des Gouvernements signataires de la Convention de Genève et des sociétés et associations de secours aux militaires blessés et malades, Berlin : J.F. Starcke, 1869.

[4] The ICRC set up at the beginning of October 1936 a special service for Spain, but its action was limited by the refusal of the belligerents to systematically send the lists of their detainees. The ‘Spanish section’ was thus prevented from fulfilling the mandate of a centralized information agency for prisoners of war. A file of more than 120,000 prisoners’ names was nevertheless established on the basis of information collected by ICRC delegates on the ground, or provided by indirect or unofficial sources. The principal achievement of the ‘Spanish section’ during the war was the transmission of Red Cross messages on a much larger scale than in WWI, when the system had first been introduced. In a country split in two in a matter of days, as postal communications were cut off, Red Cross messages were the only mean of communication available to families separated by frontlines.

[5] The draft protocol II submitted by the ICRC to the 1974-1977 Diplomatic Conference included an article 34 ‘Registration and information’ which compelled the parties to the conflict to set up information bureaux and to transmit information related to the victims of the conflict to their families, using the services of the ICRC’s Agency if needed. Participants to the Diplomatic Conference found this project too extensive and possibly infringing on the national sovereignty of the State parties. The simplified version of the draft protocol submitted by the ICRC that was finally adopted was amputated of several articles, including article 34. See also our research guide Drafting history of the 1977 Additional Protocols.

[6] For information available online on the Agency’s activity in conflicts not covered by this research guide, consult the ICRC’s annual reports, news releases, circulars and issues of the International Review of the Red Cross published during the conflict.

[7] The Central Tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross: [activities of the ICRC for the alleviation of the mental suffering of war victims] / Gradimir Djurovic. Geneva : Henry Dunant Institute, 1986, p. 18.

[8] Copies of the published lists are available in our library : Listes de blessés français recueillis par les troupes allemandes [1870-1871], Genève : [CICR] ; Bâle [etc.] : Georg, [1871] ; Liste des prisonniers de guerre allemands internés en France, Genève : [CICR], 1871.

[9] For more information, read Cédric Cotter’s article « Le CICR contre les fake news ? Rétablir la vérité pendant la Première Guerre mondiale » published on CROSS-files in 2018 (only available in French).

[10] The statistical machines used by the ACPG – originally conceived by American engineer Herrman Hollerith to help with the US census – allowed it to sort lists of prisoners to identify members of the same regiment automatically. The Agency’s collaborators could thus identify the soldiers who were most likely to know what happened to the missing person whose fate they were investigating on behalf of their family.

[11] The Central Tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross: [activities of the ICRC for the alleviation of the mental suffering of war victims] / Gradimir Djurovic. Geneva: Henry Dunant Institute, 1986, p. 215.

[12] Thirty-six years after the end of the Falklands War, an ICRC forensic team took DNA samples from the remains of 122 unknown soldiers, in the hope of identifying them and giving their families some closure. 89 of them were identified. Source: https://ihl-in-action.icrc.org/case-study/argentinauk-identification-human-remains. For further information on the ICRC’s action for the missing and their families: Missing persons project: working together to address a global human tragedy (2018).

[13] In the early 1980s, Gradimir Djurovic wrote that « the operational efficiency of the Agency ha[d] recently been increased through the acquisition of data processing equipment ». (Gradimir Djurovic, The Central Tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross: activities of the ICRC for the alleviation of the mental suffering of war victims, Geneva : Henry Dunant Institute, 1986, p. 247). The Agency has now adapted to the digital era: New technologies and new policies: the ICRC’s evolving approach to working with separated families (2012).

[14] For further information : ICRC rules on personal data protection, adopted by the ICRC Assembly on December 19 2019.

[15] Figures from the ICRC’s 2019 Annual Report, p. 98-99. All ICRC annual reports are available to read online: https://blogs.icrc.org/cross-files/annual-reports/

References of the AIPG, ACPG and CTA photographs illustrating the research guide

- The International Prisoners of War Agency: V-P-HIST-01774-21 (A ICRC (DR)); V-P-HIST-00578-26 (ICRC); V-P-HIST-00569-15 (City of Geneva/ICRC); V-P-HIST-03557-20 (A ICRC (DR)).

- The Central Prisoners of War Agency: V-P-HIST-03573-25 (A ICRC (DR)/Lacroix); V-P-HIST-00466 (StAAG/RBA); V-P-HIST-03567-15 (A ICRC (DR)/G.M.G); V-P-HIST-03556-27 (StAAG/RBA).

- Central Tracing Agency: V-P-SN-E-00349 (ICRC/José Cendon); V-P-IQ-E-02042 (ICRC/Mohammad Jawad Alhamzah); V-P-BI-N-00026-06 (ICRC/Chris Sattlberger); V-P-CY-D-00002-03 (ICRC/Max Vaterlaus); V-P-CY-D-00001-11 (ICRC/Max Vaterlaus).

Comments