Second and last part of the article A voyage through the Yemeni desert, captured on film, dedicated to the ICRC intervention during the civil war in Yemen (1962-1970).

Find here the first part.

…to actions

Breaking chains

At both ends of Yemen, relief work for prisoners of war and civilian internees [31] kept up, “gradually benefiting from the understanding and support of both royalist and republican authorities”. [32] In Sana’a, which was occupied by Egyptian troops, ICRC representatives gained permission to visit some of the detainees, in particular Muhammad al-Badr’s family. In a clip taken from the first part of “Yémen, land of suffering”, a sweeping vertical shot presents a traditional Yemeni building with barred windows. Inside are “special internees awaiting better days”, women from the royal family who have been detained in the capital. In minutes from a 16 July 1964 meeting on exchanging prisoners in neutral territory, freeing members of the royal family was one of the topics of discussion. [33] According to the document, Colonel Mohamed Schaukhat, who represented the republican forces during the negotiations, agreed to release them so that they could live freely in Sana’a, elsewhere in Yemen or in a foreign country. However, the terms applied only to members of the royal family “not including the women”, a condition added in parentheses at the end of the paragraph. In a document dated 28 July 1964, al-Badr accepted several of the terms negotiated during the meeting but requested that the women in his family be allowed to live freely in Sana’a. [34] While waiting for the two parties to come to an agreement, ICRC delegates regularly visited the interned women, bringing them “relief and news of their relatives.”

“Yemen, land of suffering”, © ICRC, director unknown, 1964, V-F-CR-H-00122.

The release of prisoners was usually the culmination of several months of negotiations. In the clip above, ICRC delegate André Rochat, surrounded by a dozen detainees, accompanies the good news that they will soon be released with a warm handshake – “their smile is his greatest reward.” With a clever shift showing the same smiling men in new outfits, they go from prisoners to civilians in a single shot. They are free and ready to leave the city of Sana’a, over which flies the ICRC flag.

For all that, in a country that up to that point had been closed to the outside world, the customs and traditional practices did not always align with the fundamental rules of humanitarian law. The ICRC was faced with some tribes who believed it “honourable to put to the sword the cowardly prisoners who had let themselves be captured”. [35] Keen to respect the Geneva Conventions to which he had agreed, al-Badr promised to pay a reward for each prisoner brought to him alive. As well, detainees were kept in conditions that were not always humane. In the clip below from “Yémen à vif”, prisoners of war wear heavy iron shackles on their ankles, joined together by chains. The chains will only be removed once they are freed.

“Yémen à vif”, © ICRC, Rochat, André, 1969, V-F-CR-H-00125.

“Yemen, land of suffering” contains a similar scene – in a Yemeni school following work by the ICRC in favor of the children of Sana’a, a boy is shown in leg irons. “In the Yemen,” the narrator explains, “the recalcitrant student may be tethered for a week.”[36] The similarity between the two images is troubling. “Other countries, other customs”, says the narrator. [37]

Operating in the desert

At the Uqd field hospital, 2,088 operations were carried out between November 1963 and its closure at the end of 1965. [38] According to the Report on Operation of the ICRC Hospital in the Yemen, “with an average of three operations per day, the morning was generally fully occupied. In fact, operations not infrequently continued well after lunch time.” [39] In spite of everything, the afternoons were usually devoted to changing dressings. Owing to the risk of vehicles being bombed from the air, the injured were generally transported in the cover of night, forcing the surgical staff to remain constantly alert.

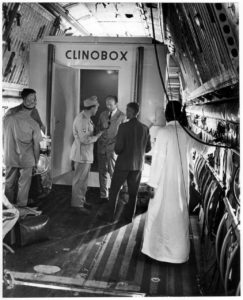

Jeddah, a plane arrives with the clinobox. © Jean Mohr, ICRC Archives, ACICR, V-P-YE-E-00418.

Considerable equipment and supplies were sent to staff in the field so they could bring medical relief to Yemeni civilians and fighters. Transport usually took several days, first by plane, then by trucks, over terrain that would challenge any vehicle. The photograph above depicts delegates André Rochat (facing the camera) and Pierre Gaillard (to his right) greeting a plane in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, that has delivered a critical piece of equipment for the Uqd hospital – the “clinobox”. Transporting the five-tonne package was highly challenging: before it could be set up in the desert, it had to be transported by truck over the course of 14 days and 1,400 kilometres. Described in the clip below as a “marvellous example of technology in the service of medicine” [40], the clinobox was highly versatile, containing instruments “permitting almost any type of operation”. [41] Outside, the clinobox had red crosses on its sides and roof; inside was an operating room of two by three metres, at most. The surgical module was fully equipped, with a sterilization area and air conditioning.

“Yemen, land of suffering”, © ICRC, director unknown, 1964, V-F-CR-H-00122.

The ICRC could also count on generous official support for its work. The Swiss Red Cross provided most of the medical and technical staff who worked at Uqd. Other National Societies sent doctors and nurses to give additional help. But on the ground humanitarians had to face another pressing problem: the climate. Uqd had no rain. Every day, a tanker truck went to the nearest well, around 25 kilometres away, to collect water, which was then rationed. For the drivers who made the trips, it was drudgery, “a constant coming and going between the hospital and the well … across tracks which were a severe trial for the tank lorries.” [42] Working in such heat was no easy task either for the hospital’s laboratory technician as she analysed specimens under a microscope. As well, with temperatures over 40 degrees Celsius in the height of summer, the odours coming from the tents quickly became hard to bear. On busy days, it was “not surprising that the [hospital’s] staff sometimes came to table at midday in [none] too pleasant a humour.” [43] As noted in “Yemen, land of suffering”, “the stress of work and the tropical heat make it impossible for the members of the medical team to stay for more than three months at Uqd”. [44]

A humanitarian encampment

“Of even greater importance than technical progress is the humanitarian ideal of the Red Cross which has become known in Yemen thanks to the ICRC’s medical action,” the Report on Operation of the ICRC Hospital in Yemen concludes. [45] The same sentiment is evident in “Yémen à vif”. No more operations carried out in the fully equipped clinobox – instead, surgery takes place in a dark room on a camp bed, under questionable hygienic conditions. Nor is there a radiologist to read a people’s suffering on an X-ray – the viewer witnesses their distress directly, with images of the wounded practically lying atop one another on the ground, of gangrenous wounds buzzing with flies and of doctors slicing into mangled flesh. [46] The scenes are blunt but necessary to conveying the weight of the difficulties and the importance of the task borne by medical staff in the field. “More than a film … a humane act of bearing witness” was the title of an article that appeared in La Suisse on 4 March 1969. [47]

“Yémen à vif” is a documentary shot on 8 mm colour film by André Rochat between December 1968 and January 1969 at the request of the ICRC. It relates the “story of a medical team of six Swiss who, between 15 December 1968 and 17 January 1969, carried out their work in a remote mountainous area”. [48] In addition to Rochat, who headed the assignment, the team comprised a surgeon, an anaesthetist and three nurses. In the film, they prepare to travel together to Jihanah, south-east of Sana’a, to treat the sick and wounded there. The viewer is transported across the Jawf desert, where mobile medical teams are traveling to work behind the front line. The 31-day assignment begins at the ICRC operational base in Najran. “It consists of a cob-walled house of just a few rooms, to which has been added the field hospital’s old clinobox, which is used to store medicines.” [49] Because security conditions during the trip are impossible to predict, “two or three days may go by before an encampment is set up”. [50] So, the team enjoy a final, hearty meal before setting out on the long and arduous journey. Some of the trucks are loaded with filtered water for the Western newcomers, who are at risk of falling sick if they drink well water too soon. A final wash, and they are ready to go. The “grand adventure” [51] begins for the medical team, accompanied by a dozen local colleagues.

After a nine-day trek through a desert studded with high mountains, all under a fiery sun, the convoy finally arrives at its destination. Described in the clip below as “typical to Yemen”, Jihanah is presented to the viewer through a shot that zooms out to show five Yemenis standing side by side. They let by the convoy, which rushes into the town, “made up of cut-stone houses, with windows closed by translucent sheets of alabaster and vivid stained glass.” Loaded with medicines and equipment, the trucks enter a “particularly solid” building, which will serve as a hospital for the rest of the assignment. One can see that the doors and windows have been walled up, to protect the injured from the cold nights. The new hospital is surrounded by houses in ruins, the result of successive bombings in the area.

“Yémen à vif”, © ICRC, Rochat, André, 1969, V-F-CR-H-00125.

According to orders drawn up in advance, “the medical team may not stay in Jihanah during the day because of the constant possibility of bombardments [52] and the lack of shelter for personnel”. [53] They can only begin to treat the wounded when night falls. Thus, they have hardly arrived at their new workplace before they are back on the road to the natural refuge selected for the assignment, caves outside of the areas targeted by the air force during the day. Once they are near the caves, several members of the team carefully find shelter for the vehicles and camouflage some. Others must already be repaired – the drivers and mechanics know that “returning to the operational base [in Najran] some 750 kilometres north will be just as arduous as the trip out”. [54] Most of the cargo is carried to the caves on the back of a donkey. The medical staff enter the Jihanah wadi and take a path to a cave “halfway up a mountain 600 metres high” [55], where they spend their days, sleeping and relaxing. Commenting on the clip below, Rochat notes that in a country still in the grips of civil war, “it’s inside this refuge that the team members find the protection they need”.

“Yémen à vif”, © ICRC, Rochat, André, 1969, V-F-CR-H-00125.

From that point, a daily routine takes shape. Just like the meals the team cooks, the sanitary facilities are rudimentary. As at the former field hospital in Uqd, water is cruelly lacking. Only the wells at the bottom of the wadi can provide what is needed. The new arrivals also discover the “fear, the immense isolation, the total estrangement from their loved ones, as well as the first demands of their interactions with the great tribes of the desert”. [56] Each day begins around 8:00 in the morning and each team member spends his day as he sees fit, taking care to rest until 5:30 in the afternoon, when Muslims are called to prayer. For the ICRC doctors and nurses, it is their signal to return to the hospital. There, they attend to 120 patients waiting for medical care in what is sometimes a superhuman effort; indeed, some are seen collapsing from exhaustion at the first light of dawn.

Conclusion

The ICRC’s work in Yemen was a milestone for the organization. At the beginning of the 1960s, under the direction of André Rochat, a handful of delegates and Swiss, German and French doctors were sent into the thick of the war in Yemen. [57] Beyond the challenges posed by any civil war, the teams in the field faced several obstacles. First, the country had no infrastructure, and the roads were difficult to drive on, if they existed at all. Humanitarians had to conduct medical activities in areas that were usually inaccessible. Yemen’s hot climate pushed them even further, sometimes to the point of recklessness, as with long desert crossings. And they were bringing relief to nomadic tribes who knew nothing of the ICRC, much less of the motivation for its work. Nevertheless, by working in Yemen, a country called a “land of suffering” [58], the ICRC was exactly where it ought to be. The organization “recognizes only one nationality to which all have a claim – that of suffering. And any suffering is a call [for help]”. [59]

Humanitarians heeded the call and worked through eight years of civil war to respond. Clips from films made in the field in Yemen show them at work, and though the hygienic conditions of the surroundings were less than ideal, their work was critical to saving lives and easing suffering. The films not only document the variety of activities carried out in Yemen but also bear witness to a fascination with the country and its people. Over the course of their assignments, the delegates and their colleagues in the field became enamoured with the traditional houses with white stonework framing the windows, and with the Yemenis themselves, in whose faces could be read the appreciation of an entire people. These films bring to the fore the full scope of humanitarianism.

Translation from French to English by Heather Thompson.

Bibliography

Works

ICRC, Annual Report 1962, ICRC, Geneva, 1963.

ICRC, Annual Report 1964, ICRC, Geneva, 1965.

ICRC, Annual Report 1965, ICRC, Geneva, 1966.

ICRC, Annual Report 2020, Vol. 2, ICRC, Geneva, 2021.

ICRC, Le C.I.C.R. et le Conflit du Yémen, ICRC, Geneva, 1964.

ICRC, “The Fundamental Principles of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement”, CROSS-Files (blog), ICRC, Geneva, 4 May 2021.

ICRC, Report on Operation of the ICRC Hospital in the Yemen, ICRC, Geneva, 1965.

“8 Mai 1989: Le Geste Humanitaire: Appel à Tous les États à l’Occasion du 125e Anniversaire du Mouvement International de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge”, Revue International de la Croix-Rouge, No. 776, Mar.–Apr. 1989, pp. 160–168.

Blondel, J.-L., From Saigon to Ho Chi Minh City: The ICRC’s Work and Transformation from 1966 to 1975, ICRC, Geneva, 2016.

Callegari, D., L’Intervention du Comité International de la Croix-Rouge au Yémen sous la Direction d’André Rochat (1963–1969), BA thesis, Geneva, University of Geneva, 2011.

Perret, F., and Bugnion, F., From Budapest to Saigon: History of the International Committee of the Red Cross 1956–1965, ICRC, Geneva, 2018.

Rochat, A., L’Homme à la Croix: Une Anticroisade, Éditions de l’Aire, Vevey, 2005.

Resources from the ICRC Archives

ACICR, B AG 062-099.02, “Yemen, land of suffering”, film requests, various organizations and individuals.

ACICR, B AG 210 225-005.01, general exchange of prisoners of war in Yemen.

ACICR, B AG 251 225-006.01, missions of 9 July 1963 to 20 May 1965 – André Rochat, head of the Yemen delegation, and André Tschiffeli, head of mission in Sanaa – aid to civilian victims and detainees owing to the war between republicans and royalists, part two.

ACICR, P AR, André Rochat fonds.

[31] A distinction is made between prisoners of war (combatants detained by an adverse party) and civilian internees, who are deprived of their liberty for pressing security reasons.

[32] ICRC, Le C.I.C.R. et le Conflit du Yémen, p. 10.

[33] ICRC Archives, ACICR, B AG 210 225-005.01, No. 43, minutes of a meeting between Abdallah ibn Hassan and Mohamed Schaukhat, 16 July 1964.

[34] ICRC Archives, ACICR, B AG 210 225-005.01, No. 44, minutes of a discussion between Muhammad al-Badr and André Rochat on exchanging prisoners in Yemen, 28 July 1964.

[35] ICRC, Le C.I.C.R. et le Conflit du Yémen, p. 8. Translated.

[36] “Yemen, land of suffering”, 00:06:12–00:06:15.

[37] Idem, 00:06:09 – 00:06:10.

[38] Annual Report 1965, p. 29.

[39] ICRC, Report on Operation of the ICRC Hospital in the Yemen, p. 2.

[40] “Yemen, land of suffering”, 00:13:18–00:13:24.

[41] ICRC, Report on Operation of the ICRC Hospital in the Yemen, p. 2.

[42] Idem, p. 3.

[43] Idem, p. 2.

[44] “Yemen, land of suffering”, 00:17:26–00:17:32.

[45] ICRC, Report on Operation of the ICRC Hospital in the Yemen, p. 9.

[46] ICRC Archives, ACICR, P AR, André Rochat fonds, newspaper article from La Suisse, 4 Mar. 1969, p. 258. Translated.

[47] Ibid.

[48] ICRC Archives, ACICR, P AR, André Rochat fonds, newspaper article from Journal de Genève, 5 Mar. 1969, p. 258. Translated.

[49] “Yémen à vif”, 00:06:22–00:06:35. Translated.

[50] Idem, 00:10:05 – 00:10:11. Translated.

[51] Idem, 00:05:01 – 00:05:04. Translated.

[52] The Egyptian air force deliberately bombarded an ICRC team in May 1967. The Egyptians also used poison gas.

[53] “Yémen à vif”, 00:18:07–00:18:20. Translated.

[54] Idem, 00:19:12 – 00:19:21. Translated.

[55] Idem, 00:19:45 – 00:19:49. Translated.

[56] Idem, 00:26:28 – 00:26:43. Translated.

[57] Among the delegates were Pascal Grellety-Bosviel and Max Récamier, two doctors from the French Red Cross who would later help found Médecins sans Frontières.

[58] “Yemen, land of suffering”.

[59] “Yémen à vif”, 00:44:10–00:44:18. Translated.

I’m not sure where you’re getting your info, but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more.

Thanks for wonderful info I was looking for this info for my mission.