Last week, the UN Refugee Agency hosted the Global Refugee Forum, an invitation-only event bringing together UN member states and powerful institutional stakeholders in Geneva, Switzerland. There, they attended presentations on refugee policy initiatives, heard from distinguished speakers and panels, took in presentations and met during receptions.

All this is vitally important. The Forum takes place as the world staggers to deal with record numbers of internally displaced persons and refugees, as the horrors of war, violence, and climate turmoil that sends them fleeing grow worse, and as squalid, already overcrowded camps pack in even more desperate souls risking death to seek sanctuary. Some governments cynically scapegoat refugees as criminals and terrorists, even deliberately subjecting them to cruelty to intimidate them from seeking the asylum that is their right. The pictures haunt like ghosts – flimsy rafts full of fleeing people, underfed refugees crowded in tent camps, terrified immigrants blocked at borders and waiting desperately to cross in crime-ridden streets, children torn from their parents’ arms and thrown into cages. We see these tragedies the world over, from Texas to Thailand to Turkey, from Mexico to Malta, from Greece to Germany to Jordan, from Uganda to the United Kingdom, from Cameroon to California.

I have been a policy-maker and I have been to conferences like the Global Refugee Forum. I know they matter and save lives. But I have also been in the streets, in the camps, and in detention centers with refugees and immigrants as a volunteer lawyer. I hope that the battered humanity of people in those cruel and desperate places was heard, seen, and felt by decision-makers last week.

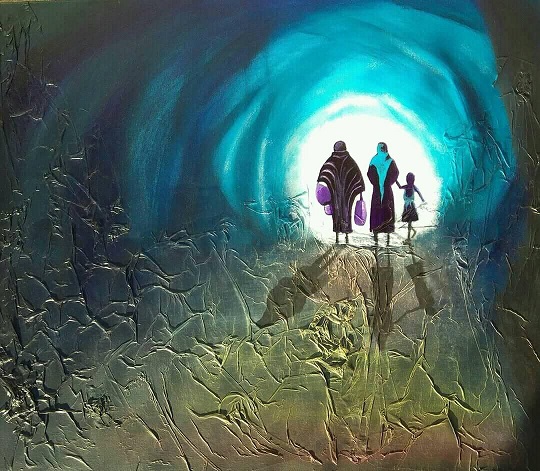

I think of those places often this season, as many of us celebrate the cherished story of the birth of a sacred child. I think of a pregnant mother and her husband, a couple of modest means, forced to make a long and perilous journey. There is no room for the couple in homes and inns, so they must stay in a scarcely sheltered place in the wintry cold. As the family prepares for the joy of new life, murderous enemies plot against them and force them to flee for their lives.

However, the family I am thinking about was not from long ago, nor was I reading their story in the Bible. The soon-to-be mother and father were Muslims from Iraq and they were right in front of me in Greece as I worked as their lawyer for an all-volunteer refugee rights group. For them, there was no stable or manger, but instead a tattered tent in a squalid refugee camp which has three times more people than it can safely hold. The camp sits atop a hill amidst freezing December winds.

The couple was terrified. We sat together in a makeshift law office—a low ceilinged attic without heat that we borrowed from a humanitarian group. The attic was cold, but it was the safest place for us to work.

The couple unbundled and told their story. They had made a long and life-threatening trip from Iraq to escape the violence there, particularly after receiving death threats for having married across religious sects. “Who threatened you,” I asked. “Our family and others,” the husband responded, with weary sadness in his eyes. They described their harrowing trip to the island, overland through several countries and finally by sea in a flimsy raft that almost capsized. The law required that they stay on the island until asylum authorities decide their cases.

“Here is our problem,” the husband continued. My god, I thought, this gets worse? “I am pregnant,” the wife said, “and the asylum office let me leave the camp and island to live elsewhere.” Good, I thought, as the law permits temporary asylum relief for vulnerable refugees. “But the asylum authority does not recognize our marriage,” the husband added. “We gave them this paper from the Imam who married us, but they say I need an official license. We do not have the paperwork. We left most of our papers in Iraq and we lost the rest at sea.”

“The authorities will not let me leave with my wife. She has been ordered to leave next week but I must stay. We will be separated, and if my asylum case is rejected, I will be forced back to Iraq and we will never see each other again.” The couple fell silent, and the husband buried his head in his hands. “It would be better if this child is never born,” he said bitterly.

“Don’t give up,” I responded. “There are ways you can stay together.” My first recommendation: Go to city hall and try to get a marriage certificate. That would keep them together, as policy dictates that married couples are not separated. Our interpreter, a Syrian Kurd, also a refugee living in the camp, asked me to come along, adding, “sometimes these things go better when it’s not just us and we have one of you.”

The interpreter, who I will call Mahmoud, is street smart about the system, so I listen to him and go. Mahmoud’s life is tragic—both parents and four brothers and sisters were killed in an airstrike in Syria. His only surviving brother won his asylum case and has a newborn nephew. They live an hour away by plane, but it would be illegal for Mahmoud to leave the camp to visit them. “I am living to see my brother and my little baby nephew,” he says. But his application for asylum was rejected. We appealed, but Mahmoud did not know if he would see his only surviving family or be deported to the merciless carnage of the war in Syria. In the meantime, he was an interpreter for three humanitarian non-profits, taught English at a refugee support house, studied for his high school degree, and applied to go to college.

“Do you have any documents about your situation?” I asked before we left. The wife reached gently into a folder and handed me an envelope, cradling it as one would hold something fragile and priceless. In it was a sonogram picture of her unborn baby. A sonogram, often happily shared as a beautiful portrait of the miracle of new life, presented here in the attic as cold, hard evidence in a legal case.

I smiled and told her “my dad would have loved this – he was a doctor and he delivered babies, and one of his favorite things was the sonogram. He called it ‘baby’s first picture.’ I wish he was here.” The couple smiled back, and for the first time since we met, they looked like a happy, young married couple about to have a baby.

Off the four of us went to city hall to get our clients married. It was a crisp and sunny day, unseasonably warm, and we could hear Christmas carols peeling from the town square nearby. O Holy Night, What Child Is This, all joyfully announcing the birth of an innocent child.

At city hall, we waited, the wife in her head scarf signaling us as likely refugees. When an official approached, I spoke first–“my friends would like a marriage license,” everything about me saying I’m a lawyer. It worked. “Come right this way,” the official politely responded.

It’s not always like that. Refugees get arrested for not having identification cards. Work with refugees is a constant lesson in how happenstance of birth, privilege and circumstance mean that some of us can come and go safely where we please and that everyone will speak our language, while others can be deported to certain death if they aren’t carrying the right papers. Power is invisible to people who have it, but seems as insurmountable as Mount Everest to the people who don’t.

The officials had bad news. They were trying to change the rules so refugees could get marriage certificates without the usual paperwork, but the changes had not yet been made. There would be no marriage license.

As we trudged back to the office at dusk, musicians played Silent Night in the town square next to a nativity scene. My stomach turned at the thought the couple’s child would be born in squalor worse than what greeted the baby Jesus. Their baby could be born in a cold, dark refugee camp. The mother might bear the child alone, thousands of miles away from a husband she would never see again. As the holy family fled as refugees from King Herod’s murderous intentions, the Iraqi couple fled from death threats. The hymn’s lyrics haunted:

Mother and child, holy infant so tender and mild, sleep in heavenly peace, sleep in heavenly peace.

We regrouped in the attic office. I gave the couple three options. One, contact UN refugee officials, who manage camp departures, and ask that the couple leave together. Two, inform Greek asylum officials that the couple’s situation called for them to be transferred from the island together. Finally, the humanitarian group lending us the attic space had a small emergency housing program for refugees at risk. We could apply for housing so the husband and wife could stay together until his case was decided. I recommended we try all three but asked the couple what they wanted to do.

The husband smiled and said, “we are sorry our case is so hard, it must be making you very tired.” I returned his smile, “Please don’t apologize, I am glad to help your family. It is what I came here to do.” This fell short of the couple’s battered, beautiful humanity, so I added, “You are trying to do such a wonderful thing. You are being a good husband and wife to each other, and you are bringing a child into the world. I am sorry it is so hard for you. I am honored to know you.”

The couple joined hands and shared some words in Arabic, and then said to me and our interpreter, “since we left Iraq, you are the first people who gave us choices and asked us what we want to do. You are the first people who cared about us. You are the first people who are on our side. Thank you.” There is a power to presence in humanitarian work, going beyond the service itself, in letting people know that you are with them and that they are not alone.

My refugee clients found sanctuary. I received a text from Mahmoud several months later: “CHARLIE!!!!! I won my appeal.” He is now near his brother and nephew and works for a non-profit that reunites refugee families. How majestic—a young man whose family was killed now working to bring families together. The UN and asylum officials agreed to transfer the married couple out of the refugee camp and off the island. They are together with their baby.

Sleep in heavenly peace.

Refugees are sacred across faith traditions. When the baby Jesus born in the stable grew up, he taught his followers to welcome and care for the stranger as they would welcome and care for God herself. Jews and Muslims follow this teaching, identical in both faiths–“to save a life is to save the whole world.”

I hope the participants at the Forum last week experienced the sacredness and humanity of refugees as I did. Their stories, a million times over, end tragically, not happily. Countries need to be held accountable for the neglect that forces refugees to flee and leaves them stranded with nothing but deadly options. Countries need to be held accountable for the war and violence that target civilians, forcing vulnerable people to live on the front lines of climate turmoil, and for the deliberate cruelty to refugees, as brutal as war crimes and as widespread as mass atrocity. This global crisis demands a multinational global solution that prioritizes refugee sanctuary the same way the Paris Agreement prioritizes protecting the planet from global warming. A Forum that does these things would answer the prayers of millions of the world’s most vulnerable and sacred souls, and perhaps save ours as well.

See also

- Claudena M. Skran, Gustave Ador, the ICRC, and leadership on refugee and migration policy, January 30, 2018

- Sir Michael Aaronson, Refugees, migrants, IDPs: Protecting people on the move – without distinction, October 9, 2017

- ICRC, How does IHL protect refugees and internally displaced person? August 14, 2017

- Conference Report, Forced to flee: A multi-disciplinary conference on internal displacement, migration and refugee crises, International Review of the Red Cross, 2017

- Pavle Kilibarda, European ‘migrant crisis’: Avoiding another wave of refugees living in limbo, June 23, 2016

Yes, the pioneering work of the ICRC regarding refugees in the Interwar Period of 1919-1939 has been documented. It is true that the ICRC had a very large role with the League of Nations in responding to refugee problems. In fact, the head of what became the Nansen Office or the League of Nations refugee office was first offered to Gustav Ador, and other ICRC officials played a large role in supporting Nansen.

Humanity is in all of us – we need a political solution.