Can military training in international humanitarian law (IHL) lead to greater adherence to IHL and increased protection for civilians in war?

In this post, Andrew Bell, a researcher in the ICRC’s Centre for Operational Research and Experience (CORE), outlines recent findings from his work reviewing results from U.S. Army surveys on the effects of IHL training on combatant views and behaviour in war. He demonstrates that training in IHL and norms of restraint can achieve significant effects in military forces, shaping both combatant attitudes and behaviour and generating more restraint in battlefield operations.

Every year, the ICRC and other nongovernmental and governmental organizations train hundreds of thousands of soldiers and fighters around the world in the principles of IHL. But, despite this massive global effort dedicated to promoting IHL among military forces, to date little systematic quantitative research has examined whether IHL training actually influences both combatants’ attitudes and battlefield behaviour. And, even with the insights generated by a few important studies—including, notably, the ICRC’s Roots of Restraint in War study – we still have a great deal to learn as to whether IHL training can actually achieve effects in improving military conduct in war.

Prior empirical research has examined the effects of IHL and combat ethics – known more generally as “norms of restraint” – on combatant attitudes. In this post, I examine the effect of such training on combatant behaviour, highlighting original research on U.S. Army training and conduct during the conflicts in Iraq (2003-2010) and Afghanistan (2001-2021), drawing on original surveys with U.S. Army officer trainees and behavioural surveys with U.S. Army combat veterans.[1]

As this research shows, training in IHL and norms of restraint can achieve significant effects in military forces, shaping both combatant attitudes and behaviour in battlefield operations. IHL training and other efforts to promote norms of restraint thus represent vital tools for improving civilian protection outcomes, increasing adherence to military rules of engagement (ROE), and enhancing the disciplined use of force by military organizations.

Analytical background

Decades of social science research shows that individuals’ conduct is shaped both by personal attitudes and the social norms of individuals’ social communities and networks. These social norms – “standards of appropriate behavior for actors with a given identity” – in turn influence not only how people act in any given situation but also their attitudes for whether these actions are “correct” according to their broader social communities. In militaries, the influence of these norms (including through ideology and culture) can be extremely powerful.

Building on this analytical framework, this research tests the impact of norms and norms training – and, particularly, IHL and combat ethics – in influencing combatants’ attitudes and actions in combat.

In doing so, this research investigates three primary questions:

- Does increased training in IHL and combat ethics lead to greater adoption of norms of restraint and increased emphasis on civilian protection by combatants?

- Does increased training in IHL and combat ethics lead commanders to promote norms of restraint and civilian protection more in combat?

- Does increased emphasis on values or ethics by commanders lead to greater restraint and increased adherence to ROE by their units?

The answers to these questions can guide humanitarian actors and military organizations in promoting norms of restraint among armed forces, non-state armed groups, and other combatant forces.

Question 1: Does increased training in IHL norms lead to greater adoption of norms of restraint?

To answer this question, this research compares the impact of high- and low-intensity training in IHL norms, examining IHL training at three different U.S. Army officer training institutions: the Army’s four-year U.S. Military Academy (USMA–categorized as high-intensity IHL training based on training hours); Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), a part-time military training program at civilian universities (low-intensity IHL training); and Officer Candidate School (OCS), a three-month officer training program (low-intensity IHL training). These three programs train to an identical normative basis – norms of restraint as found in IHL, the “Army Ethic,” the Army Values, and U.S. military law – but vary the intensity and method of training.[2]

To measure the effect of this training, I administered surveys to 1,126 Army officer trainees at either the beginning or end of their training at these programs.[3] Surveys presented multiple ethical dilemmas based in a “combatant’s trilemma”, hypothetical scenarios that forced respondents to balance the values of military advantage, force protection, and civilian protection.

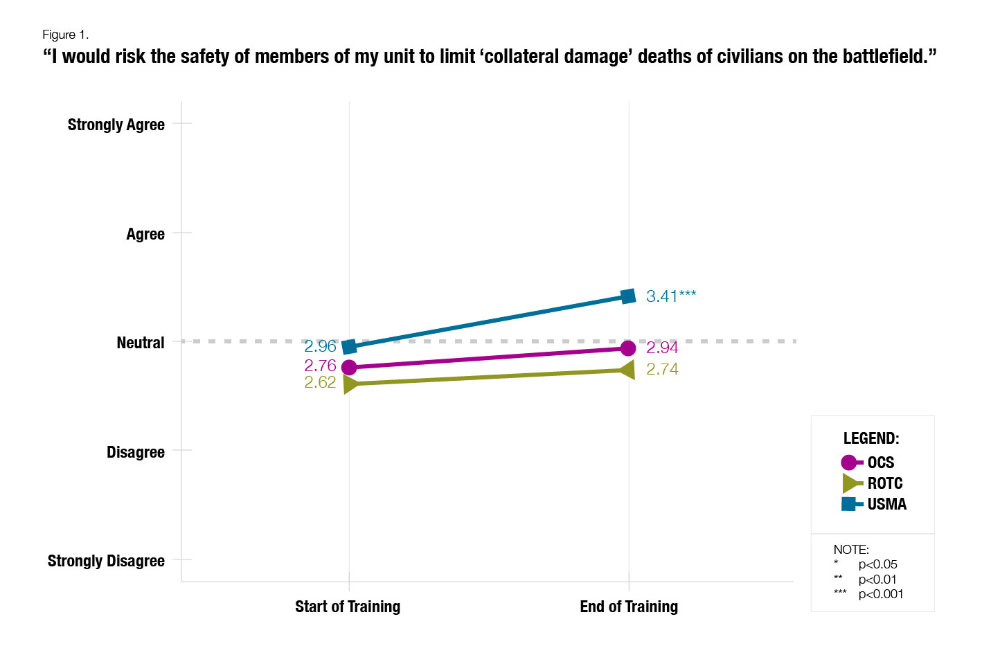

Across this and a range of similar questions, trainees’ responses reveal that increased IHL training results in greater emphasis on civilian protection. For example, one question asked survey participants to provide their views regarding the following dilemma: “I would risk the safety of members of my unit to limit ‘collateral damage’ deaths of civilians on the battlefield.” (Response categories used a 5-point scale, from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”).

At all three training programs, officer trainees at the start of training were generally ambivalent or prioritized force protection; and, accordingly, low-intensity IHL training (ROTC and OCS) resulted in slight or no change in attitudes by the end of training (see Figure 1 below). However, high-intensity IHL training (USMA) generated a significant shift in trainees’ responses toward restraint, with USMA cadets prioritizing civilian protection even over force protection (Figure 1). (A “control” sample of civilian university students showed no change between the beginning and end of university, indicating these shifts do not result merely from university-age education or development).

The results of this research demonstrate two important points: first, IHL training can influence military attitudes, even at relatively low levels of intensity. While this training produced little effect in dilemmas balancing civilian protection with force protection, low-intensity training produced greater emphasis on restraint in scenarios balancing military objectives against civilian protection. Thus, even low-intensity IHL training can achieve effects in shaping combatant attitudes toward civilians.

Additionally, these results also show that increased IHL training can lead to greater levels of norm adoption: high-intensity IHL training significantly shifts combatant attitudes toward restraint, potentially even leading them to prioritize civilian protection over force protection.

Question 2: Does increased training in IHL norms lead commanders to promote norms of restraint more in combat?

While it is one thing for IHL training to shape combatant attitudes, it is quite another to impact the actual conduct of military forces on the ground. To further examine the influence of IHL training on wartime conduct, I conducted a behavioural survey of U.S. Army combat veterans that asked participants about their experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In one question, the survey asked combat veterans to assess the degree to which their unit leaders (officer graduates of USMA, ROTC, or OCS) emphasized the following: IHL rule enforcement, prioritization of civilian protection, ethical values, and general (non-IHL) rule enforcement.

Consistent with the officer training surveys above, veteran surveys indicate that unit leaders from high-intensity IHL training (USMA) emphasized restraint in combat significantly more than unit leaders from low-intensity training programs (ROTC and OCS). USMA graduates enforced IHL rules more often than non-USMA counterparts; results suggest that USMA-trained unit leaders also emphasized military values and ethics and prioritized the protection of civilians more than non-USMA leaders as well (Figure 2).[4]

Notably, however, there was no statistical difference between USMA- and non-USMA-trained leaders in general (non-IHL) rule enforcement. Thus, while USMA and non-USMA unit leaders impose overall unit discipline at relatively equivalent rates, USMA graduates promote IHL and ethics in combat more than other leaders – conduct likely attributable in part to USMA’s high-intensity IHL training environment. Increased IHL training thus appears to lead commanders to increase emphasis on norms of restraint in combat.

Question 3: Does increased emphasis on norms of restraint by commanders lead to greater restraint by their units?

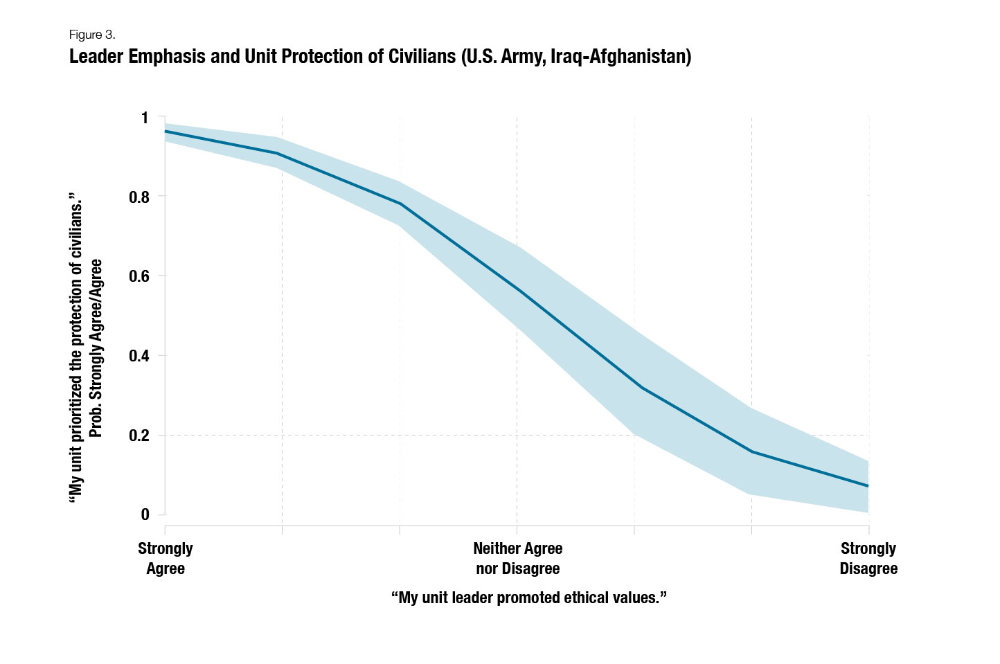

Finally, to further investigate how norms of restraint can influence both military command and unit conduct, the survey asked participants to characterize the relationship between their unit’s conduct toward civilians and their unit leader’s emphasis on combat ethics and values.

To assess the impact of leader emphasis, the survey provided the prompt: “During my deployment, my unit leader emphasized to my unit that protecting civilians was important because of ‘who we are as American soldiers’ or because it’s ‘the right thing to do’ (using these or similar words)” (7-point response scale, “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”). To capture unit behaviour toward civilians, survey participants were asked to respond to the following prompt: “During my deployment, my unit prioritized the protection of civilians” (7-point response scale, “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree”).

As Figure 3 shows, there is an extremely strong connection between a unit leader’s emphasis on norms of restraint and the unit’s conduct: units whose leaders emphasized ethics and values prioritized civilian protection much more than units whose leaders did not. This relationship holds even when accounting for other potential influence factors, such as unit discipline, enemy threat, length of time under fire, population density, unit morale, and deployment year (a measure for the shift in U.S. counterinsurgency policy in 2006).

To ensure that these results did not result from random chance, the survey asked multiple related questions on leadership emphasis and unit conduct – all of which produced results similar to these.

In sum, the research outlined here provides important new empirical data regarding the three research questions outlined above. This data shows that:

- increased training in IHL and combat ethics can shape combatants’ attitudes, leading to greater emphasis on civilian protection and norms of restraint by combatants;

- increased IHL training correlates with greater emphasis on civilian protection and norms of restraint by commanders in combat; and

- commanders’ emphasis on values or ethics can result in greater emphasis on civilian protection and norms of restraint by military units in combat.

Recommendations

This research provides compelling evidence that IHL norms can significantly influence the behaviour of combatants and units, helping to achieve greater discipline in the use of force and increased adherence to IHL principles in war.

While some may claim that training in such principles only constrains military forces and reduces combat effectiveness, such training can in fact enhance the tactical discipline and operational capabilities of combatants and commanders, particularly in civilian-dense environments.

Based on these findings, some recommendations can be made for humanitarian, military, and governmental actors seeking to promote the protection of civilians and increase combatants’ adherence to IHL. First, humanitarian organizations, working with military forces, should increase the intensity, duration, and scope of training in IHL, combat ethics, and norms of restraint currently undertaken by combatants within these forces.

Similarly, militaries, in conjunction with humanitarian organizations where appropriate, should promote both IHL norms and increased command capacity – such as through greater involvement of legal advisors – for leaders and commanders within the military. Such efforts can increase commanders’ interest and ability to promote IHL norms and direct and constrain the force exercised by units under their command.

Finally, humanitarian organizations, working with governmental and military organizations, should intensify research into the practices and policies that can most effectively promote the adoption and implementation of combat ethics and norms of restraint in war. Importantly, such research can increase the effectiveness of such efforts in training contexts marked by limited time and resources, as is often the case in ethics and IHL training settings.

Together, the research outlined in this post provides new evidence that IHL, ethics, and norms of restraint can shape combat behaviour: IHL norms and training can increase civilian protection and generate measurable effects in promoting the protection of civilians on the battlefield. Such evidence shows that now – more than ever – humanitarian and other actors must intensify efforts to promote norms of restraint and protect those most vulnerable in war.

[1] This research received institutional review board (IRB) approval from Duke University, Indiana University, and the U.S. Military Academy.

[2] “IHL training” in this post refers to the collective package of training in the principles of IHL, military ethics, and military law that U.S. Army combatants receive during their training programs.

[3] This research study is described more fully in an academic journal available here; an ungated version of this research study is also available here.

[4] Due to sample size, “Leader Values” and “Prioritize Civilians” results are directionally consistent but below conventional thresholds of statistical significance.

See also:

- Giulio Bartolini, Voluntary reports: a new tool ‘toward a universal culture of compliance with IHL’, April 11, 2024

- Jacob Coffelt, Codifying IHL before Lieber and Dunant: the 1820 treaty for the regularization of war, April 4, 2024

- Tilman Rodenhäuser, Samit D’Cunha, Foghorns of war: IHL and information operations during armed conflict, October 12, 2023

- Tilman Rodenhäuser, Mauro Vignati, 8 rules for “civilian hackers” during war, and 4 obligations for states to restrain them, October 4, 2023

Comments