Two years ago, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Central Tracing Agency activated a dedicated Bureau for the international armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the first time since the Gulf Wars. The role of such a Bureau includes helping locate missing persons. While this is a key function of the ICRC’s Central Tracing Agency, there is more to its role specifically during an international armed conflict that is worth re-discovering.

In this post, Natalie Klein-Kelly, ICRC’s Transformation Programme Manager for the Central Tracing Agency, Karen Loehner, ICRC’s National Information Bureau Manager, and Jelena Milosevic Lepotic, Head of Protection of Family Links unit, share their reflections on the contemporary relevance and the historical origins of the ICRC’s Central Tracing Agency. They show the importance of reviving certain activities, such as the transmission of information on protected persons between the parties, that is specific to this type of conflict that humanitarian actors may be less used to operating in, following past decades that were dominated by non-international armed conflicts and other situations of violence.

In view of the new realities in global geopolitics, there is a need to regain familiarity with the legal and protection fundamentals of international armed conflicts (IAC), specifically those foreseen by the Geneva Conventions of 1949. They foresee, in the context of an armed conflict between two or more states, the protection of distinct categories of persons who find themselves in enemy hands, i.e. in the hands of a party to the conflict they do not belong to, or of which they are not nationals.[1] They also provide, to some extent, the basis on which humanitarian actors can and must operate: this is the case for the ICRC Central Tracing Agency (CTA).

The CTA offers an essential means to reconnect people in enemy hands to the Power they depend on, the country of their nationality or last residence[2], and ultimately to their families. States who are parties[3] to an international armed conflict must, among others, account for enemy protected persons in their hands, i.e. prisoners of war, enemy deceased military, and other interned or detained protected persons. This includes providing the CTA with information on their fate and whereabouts. The CTA is specifically mandated by the Geneva Conventions to collect this and transmit it from one side to the other, acting as a neutral intermediary and safe repository.

While the assumption in the Third Geneva Convention is that there are benefits for prisoners of war to have the power upon which they depend know about their fate and whereabouts, the Fourth Geneva Convention provides for an exception to transmission in case the protected persons concerned consider such a transmission detrimental to them or their families. In such a case, the CTA must be informed of such concerns so that it can take the necessary precautions, including deciding not to transmit. The ICRC considers that the same exception applies to prisoners of war.

The late 19th and early 20th century historical wartime origins of the ICRC’s Tracing Agencies

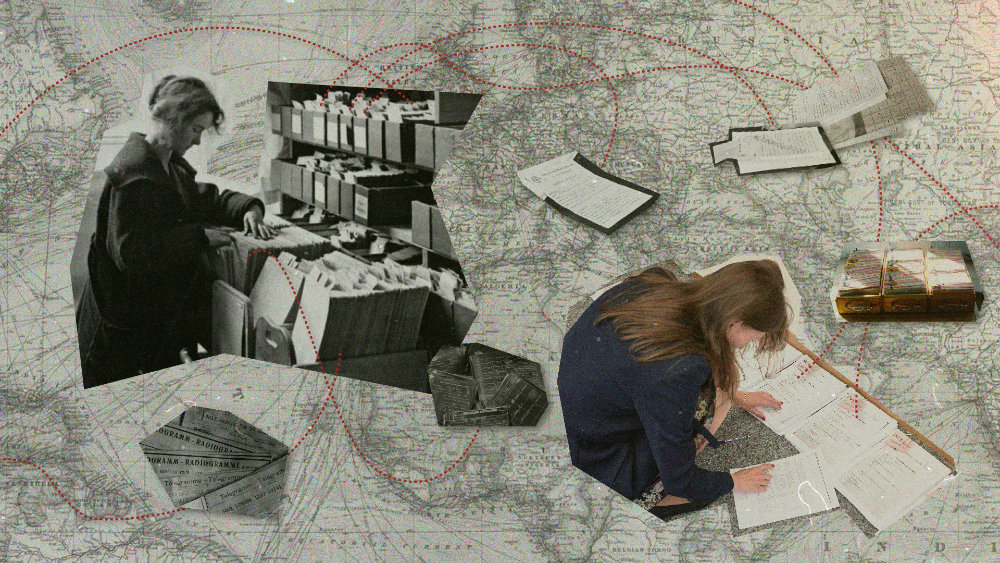

The origins of the ICRC’s and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement’s tracing activities date back to the Franco-Prussian conflict in the 1870s, when the ICRC set up the so-called “Basel Agency”. This agency started by transferring letters between prisoners of war and their families from one (state) postal system to the other. This very practical intermediary action was essential, as postal services had ceased their cross-border operations.

Activities expanded further, also during the World Wars, when the ICRC’s Tracing Agencies – one Agency per World War – became “the beating heart of Europe”[4]: they obtained information from belligerent states on combatants in their hands, as well as others interned, and transmitted this to the adverse party, while safeguarding this information. This enabled the tracking and tracing of millions of individuals separated from their states and from their families. The historical and long-term importance of first World War Agency’s resulting archive, holding information on two million persons, was recognized when it joined the UNESCO World Heritage List.[5]

These early tracing activities are, therefore, best understood in the context of sovereign states at war, and the situation where people find themselves outside the protection of their own state.[6] This included prisoners of war, but also ‘enemy aliens’, i.e. civilians who found themselves in enemy territory. As the number of representatives of neutral countries offering services to such ‘trapped enemies’ shrank over the course of the First World War, the importance of the ICRC’s Tracing Agencies tracking and tracing of such ‘aliens’ grew.[7]

Not only did these Agencies transmit information between belligerent states on their own military or civilian citizens, but, by the end of the conflicts and often for years to follow, they were working on issuing a range of attestations and travel documents for these groups of persons, in lieu of their states. Sometimes this was because their state could not be reached, sometimes because there was no longer a state; in any case, persons relied on the Tracing Agencies having collected, kept, and safeguarded their data. In the case of foreign persons on German territory in 1945, including survivors of Nazi persecution and forced laborers, the dedicated Tracing Agency for this group of persons, now called the Arolsen Archives, still issues attestations today, and also uses this safeguarded data to connect families, 75 years later.[8]

Shifting perspectives in the late 20th Century: focus on your family bond (only)

In the 1970s, an ICRC delegate lamented the “crazy situation of today’s international law where the alien is better protected than your own national”.[9] By the 1990s, the focus on international human rights law, also within the humanitarian sector, had indeed increased.[10]

For the ICRC and its tracing activities, this meant that the focus shifted away from its role as an intermediary between states as parties to a conflict to a role as an intermediary between a person and his or her state or non-state armed group(s) – or, simply put, between separated family members with potentially no state involvement. Rather than relying on receiving information on persons from the belligerent states, as it did in its early history, the CTA adapted its action to collect information through other means, including through its visits to places of detention.

Operationally, it also meant that the activity of Tracing Agencies typically started with a request to locate a missing person from the family or requests from the person-in-need themselves, rather than – as in the World Wars – with information being transmitted from the parties.[11] With this logic, activities could also greatly expand in the second half of the 20th century to other situations of violence, disasters and migration, thanks to the size and capacity of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement’s Family Links Network.

Today, over 160 National Societies are part of this powerful network that can, very practically, help families find each other and stay in touch in different corners of the world. In order to ensure the continuity of the coordination and advisory role towards this network, a permanent “Central Tracing Agency” was formed within the ICRC in the 1960s.

Who should the Central Tracing Agency inform: families or states, and what is the difference?

From the perspective of a person in need of protection, separated from the power they belong to or from their state of nationality, and likely also from their family, both connections – to state and to family – are meant to serve to obtain protection and assistance. To give just one practical example: prisoner of war direct repatriation or accommodation in neutral countries, for example for medical reasons, are typically arranged through state auspices; hence, a state knowing who of its members of armed forces has been captured and what their health status is can be instrumental to arranging such measures, including on the basis of agreements between the Parties, as foreseen by the Third Geneva Convention. Very practically speaking, in an IAC, the Third Geneva Convention presumes that a state has a relationship with the families of its servicemen, who may come to expect information and support from their own authorities.

With the above in mind and looking at the specificities of IACs and what the Geneva Conventions foresee, the global understanding of the CTA’s role in an international armed conflict should not be limited to how many persons it manages to locate at the request of families. This additional role of the CTA vis-à-vis families is primarily to help those falling between the cracks of this system: for example, families that cannot be reached by their own state, maybe because they are resident in another state’s territory, or they have been displaced. As such, families, also in the World Wars, have always directly approached the ICRC’s Tracing Agencies with their diverse needs.

For a full understanding of the mandate of the CTA in an international armed conflict, the focus needs to shift (back) to the system foreseen in the Geneva Conventions as regards states’ obligations to account for those in their hands, through the ICRC’s CTA, which transmits the information to the state concerned, who, in turn, informs the families. This system also allows the CTA to safeguard the information on the fate and whereabouts of those persons, available to the protected persons themselves and their families, for the longue durée.

[1] While the nationality of a person is a criterion to be considered a “protected person” under Article 4 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, it is not a criterion to be considered a Prisoner of War under Article 4 A, Third Geneva Convention.

[2] See Article 123, Third Geneva Convention and 140, Fourth Geneva Convention, which foresee the transmission of information by the CTA on prisoners of war (PoWs) to the Power upon which they depend or their country of origin, and for other protected persons the country of nationality or last residence, respectively.

[3] Such obligations equally apply to neutral states receiving such persons on their territory in the case they would decide to intern them.

[4] Stefan Zweig, Das Herz Europas. Ein Besuch im Genfer Roten Kreuz, Zürich 1918.

[5] Gradimir Djurovic, L’Agence Central de Recherches du Comité International de la Croix-Rouge. Activité du CICR en vue du soulagement des souffrances morales des victimes de guerre, Institut Henry Dunant, Genève 1981.

[6] Robert Jackson, Sovereignty. The Evolution of an Idea, Polity Press, Cambridge 2007, particularly pp. 149 and 154.

[7] Daniela L. Caglioti, War and Citizenship. Enemy Aliens and National belonging from the French Revolution to the First World War, Cambridge University Press 2021.

[8] Original name “International Tracing Service”, under ICRC management until 2012; see: International center on the Nazi era – Arolsen Archives (arolsen-archives.org)

[9] Address by Jacques Moreillon, ICRC Delegate-General for Africa, 1975 (ICRC Archives, B AG 225 231-004) as quoted in Andrew Thompson, Restoring hope when all hope was lost: Nelson Mandela, the ICRC and the protection of political detainees in apartheid South Africa. IRRC Vol. 98, Issue 90 (2016), pp. 799-829.

[10] Stephen Hopgood, For a fleeting Moment: The short, Happy Life of Modern Humanism, in Michael Barnett (ed.), Humanitarianism and Human Rights: A World of Difference, Cambridge University Press 2020, p. 89-104.

[11] In World War Two, capture cards were distributed to and filled by prisoners of war and sent to the ICRC’s Tracing Agency. This is, in essence, a first way for the detaining Power to account for those PoWs; and a request from the person seeking protection to the ICRC to start tracking his fate and whereabouts, and safeguard this information, also for instance, for his own future need of attestations. For the post-World War capture cards see IHL Treaties – Geneva Convention (III) on Prisoners of War, 1949 – Article 70 (icrc.org).

See also:

- Ellen Policinski, Prisoners of war in contemporary armed conflict: Interpreting the Third Geneva Convention 70+ years after its negotiation, August 11, 2022

- Ramin Mahnad, In the hands of belligerents: status and protection under the Geneva Conventions, May 19, 2022

- Helen Obregón Gieseken, Ximena Londoño, Looking for answers: accounting for the separated, missing and dead in international armed conflicts, April 11, 2022

- Ximena Londoño, Helen Obregón Gieseken, Sustaining the momentum: working to prevent and address enforced disappearances, August 26, 2021

- Filipa Schmitz Guinote, Eva Svoboda, Where are they? Three things the families of missing persons teach us about war and peace, May 6, 2021

- Cordula Droege, GCIII Commentary: ten essential protections for prisoners of war, July 23, 2020

Comments