Whenever human and material resources begin to dwindle, decision-makers face tough and often tragic choices. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic presents the most recent illustration of this point: governments around the world have had to reprioritize public spending, which has already had grave effects for a number of lower-priority sectors such as tourism or culture.

The question of resource scarcity during armed conflicts, which impacts war-affected populations and belligerent parties alike, is one to which the ICRC Commentaries team has returned repeatedly. For example, in the context of the Common Article 3 obligation to collect the wounded and sick in non-international armed conflicts, the Commentary notes that ‘the Convention does not require Parties to do the impossible, but they must do what is feasible under the given circumstances, taking into account all available resources’ (para. 790). Similarly, with respect to the obligation to care for the wounded and sick in international armed conflicts, the Commentary on Article 12 of the First and Second Conventions explains that ‘the medical personnel of a Party which has significant resources at its disposal can be expected and will therefore be required to do more than the medical personnel of a Party which has limited means’ (para. 1382 and para. 1427, respectively).

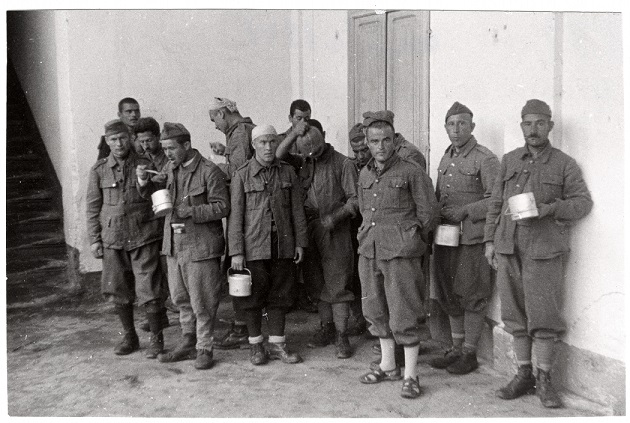

During the drafting of the GCIII Commentary, we were faced with a novel angle on this problem. As most readers of this blog know well, the Third Convention contains rules for the protection of prisoners of war (POWs) who fall into enemy hands during international armed conflicts. Some of these protections, like the prohibition of physical mutilation in Article 13(1), reflect negative obligations and are as such resource-neutral: they require the Detaining Power to abstain from certain forms of conduct. However, other rules – particularly those that lay down positive obligations – can be quite resource-intensive. These include, for example, provisions that require the Detaining Power to provide prisoners with sufficient daily food rations (Article 26), access to clean bathroom and laundry facilities (Article 29), or to equip each camp with its own infirmary to attend to the health-care needs of POWs (Article 30). In the context of such rules, the question arises as to the legal consequences of material inability to fulfill the prescribed obligations.

Unable or unwilling?

Before going further, it is important to distinguish the notions of inability and unwillingness. It is not particularly controversial to say that the lack of will to comply with a legal rule is irrelevant for the operation of that rule. I might be unwilling to look at the traffic light as I am crossing the street. I might even look at it, see it is red, and cross anyway – but my lack of will to behave in a rule-compliant manner will not alter the fact that I have just violated a legal rule and thus exposed myself to a fine. In that regard, traffic rules and the rules of international humanitarian law (IHL) are no different: as I have argued elsewhere, an actor’s unwillingness to apply IHL does not excuse that actor’s unlawful conduct (pp. 206–207).

However, what happens if the Detaining Power is truly unable to meet its obligations towards the POWs in its power? Perhaps the armed forces capture a larger number of enemy troops, but they lack the material resources needed to set up POW camps. Perhaps an existing camp in a remote location gets cut off from its regular supplies as the operational reality on the ground suddenly changes. Or perhaps the conflict-fuelled collapse of government and military structures and institutions (the so-called ‘failing State’ phenomenon) gradually eliminates the State’s ability to meet the needs of the previously interned POWs.

Such forms of inability do not excuse non-compliance. Article 1 common to the Geneva Conventions mandates that States must respect the Conventions ‘in all circumstances’. This means that compliance is not made contingent on one’s capacity, with the possible exception of those provisions that either reflect an obligation of means or impose a minimum standard (see para. 220 of the new Commentary). For instance, the obligation to care for the wounded and sick mentioned above falls into both of these categories: above the minimum first aid and basic care, the belligerents are required to do the best they can in the prevailing security situation and with capacities available to them (see also the Commentary on Article 12 of the First Convention, para. 1379). By contrast, the Article 26 obligation to provide POWs with sufficient food imposes an obligation of result and as such constitutes an irreducible minimum. Failure to do so thus qualifies as a violation of IHL even if it was caused by a lack of resources. But what are the legal consequences of such violation?

Authority to intern

One possible solution is to interpret, as Ryan Goodman and Derek Jinks did in a 2005 article, the compliance with the minimum requirements under the Third Convention as ‘a condition of the power to detain’ (at p. 2661). The Convention provides the legal basis to intern captured military personnel in Article 21(1), according to which ‘[t]he Detaining Power may subject prisoners of war to internment.’ Under the Goodman-Jinks approach, that authority to intern is contingent on the ‘observance of minimum standards’ under the Convention; if belligerents are unable to meet those standards, they must either release and repatriate the affected POWs or arrange for them to be detained in a neutral State.

This solution is certainly appealing from a protection perspective. Few would dispute the suggestion that POWs who cannot be given the minimum (read: life-sustaining) treatment should be either released or at the very least moved somewhere where such treatment is available.* It also aligns with the policy preference expressed in the 1960 ICRC Commentary on the Third Convention, which argued that ‘[i]f the Detaining Power is unable or unwilling to fulfil its obligations in respect of maintenance, it should no longer detain any prisoners of war’ (p. 153, emphasis added).

However, it is doubtful whether such conditionality can be read into the text of Article 21. The Third Convention is clear on when the authority to intern lapses by laying down an obligation to release and repatriate POWs after the cessation of active hostilities (Article 118(1)), unless they are subject to criminal proceedings or are serving a criminal sentence (Article 119(5)). Accordingly, so long as hostilities are ongoing, the parties to the conflict retain the authority to intern enemy personnel under the Third Convention. No other exception is apparent from the text of the Convention and the legal solution must thus be sought elsewhere.

IHL and State responsibility

It should be remembered that the Geneva Conventions, along with the rest of IHL, form part of the much broader corpus of public international law. As such, they are subject to rules of general international law such as those on law creation, treaty interpretation, and State responsibility. It is the last-named body of rules, i.e., the law of State responsibility, which also provides the key to the question at hand.

Rules on the treatment of POWs in the Third Convention set out what the International Law Commission’s commentary on the Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA) describes as ‘primary obligations’ of international law. When the conduct of the Detaining Power falls short of what is required of it by any of these primary obligations—for example, when it fails to provide POWs in its power with sufficient food—it will have committed an internationally wrongful act, or in other words, it will be in violation of international (humanitarian) law. Because the State’s conduct would not be in conformity with the relevant obligation for as long as it failed to feed the prisoners to the required standard, its violation would be considered to have a continuing character (see the commentary on Article 14 ARSIWA, para. 3).

In accordance with the well-established rules of State responsibility, a violation of a primary rule of international law triggers the responsible State’s secondary obligations, key among which is the obligation of cessation reflected in Article 30(a) ARSIWA. That secondary obligation requires the responsible State to cease its wrongful conduct, if it is continuing. As Olivier Corten put it (at p. 548), ‘[i]n law, a State must and can always put an end to a continuing breach.’

The Holmes solution

Translated back into the context of the Third Convention, there may be several ways that the responsible Detaining Power can put an end to a continuing breach of its primary obligations under the Convention. To begin with, if at all possible, it should reallocate resources without delay so as to meet its obligations. If that cannot be done, the new ICRC Commentary highlights (at para. 114) a spectrum of alternative ‘appropriate measures’ that the Detaining Power may take, including:

- requesting or accepting assistance from other States;

- requesting or accepting assistance from an impartial humanitarian organization like the ICRC; or

- transferring the prisoners to another Power, subject to Article 12.

If none of these measures are available and if there is no other option for the Detaining Power to cease the continuing breach of its primary obligations under the Convention, then, ultimately, it is obliged to release and repatriate the POWs in question.** To paraphrase Sherlock Holmes, when we have eliminated all other options, then the one which remains must be the correct one.

Overall, this legal solution provides a practical answer to the problem posed by the lack of resources on part of the Detaining Power. At the same time, it respects the text of the Third Convention and interprets it within the framework of the modern international legal system. It preserves the authority to detain laid down by Article 21 and clarifies the narrow set of circumstances in which the Detaining Power may, as a matter of law, be required to let go those it cannot feed.

* The latter is envisaged by some provisions in the Third Convention, including Article 22(2) and Article 30(2), although not systematically; see also the 2020 commentary on Article 29, para. 2195.

** For a specific application of this analysis to the relevant articles of the Third Convention, see paras 1357, 1526, 1721, 1940, and 2119 of the new Commentary.

See also

- Catherine O’Rourke, Geneva Convention III Commentary: What Significance for Women’s Rights?, October 21, 2020 (published in Just Security)

- Jemma Arman, GCIII Commentary: protecting the honour of prisoners of war, September 3, 2020

- Cordula Droege, GCIII Commentary: ten essential protections for prisoners of war, July 23, 2020

- Jean-Marie Henckaerts, GCIII Commentary: ICRC unveils first update in sixty years, June 18, 2020

- Jean-Marie Henckaerts, Joint series: Locating the Geneva Conventions Commentaries in the international legal landscape, June 29, 2017

Comments