Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer was an important figure of the International Committee of the Red Cross in the early 20th century. A legal scholar and historian, she became the first woman member of the Committee. During the First and Second World Wars, she played a central role in the activities of the Tracing Agencies founded to bring relief to prisoners of war and inform their families about their fate. One of the main authors of the 1929 Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, she also tirelessly advocated for the development of an international legal protection for civilians in wartime during the 1930s and 40s.

An Early Career in Academia

Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer was born in Geneva on December 28th, 1887. Her family belonged to the local bourgeoisie, the social class that had turned to banking and philanthropic activities at the end of the 19th century, after losing control of the major public offices in Geneva.[1] Even before joining the ICRC, she had an important network within the organization. Her maternal grandfather, Louis Micheli, was actually one of the Committee’s early members.[2]

Renée-Marguerite studied both history and law, in Geneva and Paris. In the early 20th century, it was not exceptional for a woman to go to university in Switzerland: women represented almost a fourth of the enrolled students.[3] But her choice of studies was surprising, as Swiss women usually pursued degrees in medicine and science. After graduating with a law degree in 1910,[4] Renée-Marguerite decided against pursuing a career as an attorney and started to research constitutional law and national history. She wrote a series of essays on the principle of nationalities, on the prosecution of teenagers, and on the history of Geneva,[5] and continued her historical research after getting her doctorate in law.

As a historian, Renée-Marguerite grew interested in the questions of her time, writing about nationality and national identity. Her work was well-received: she was awarded twice the prestigious prix Ador.[6] She studied Geneva’s evolving identity and its relations with its neighbors. Her most extensive historical work Genève et les Suisses: histoire des négociations préliminaires à l’entrée de Genève dans le corps helvétique 1691-1792 was published in 1914, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Geneva joining the Helvetic Confederation. In 1918, Renée-Marguerite was asked to replace the Pr. Charles Borgeaud, one of her relatives, to teach the history of Geneva.[7] She became the first woman historian to get a position as a substitute professor in Switzerland.[8]

Working for the International Prisoners of War Agency

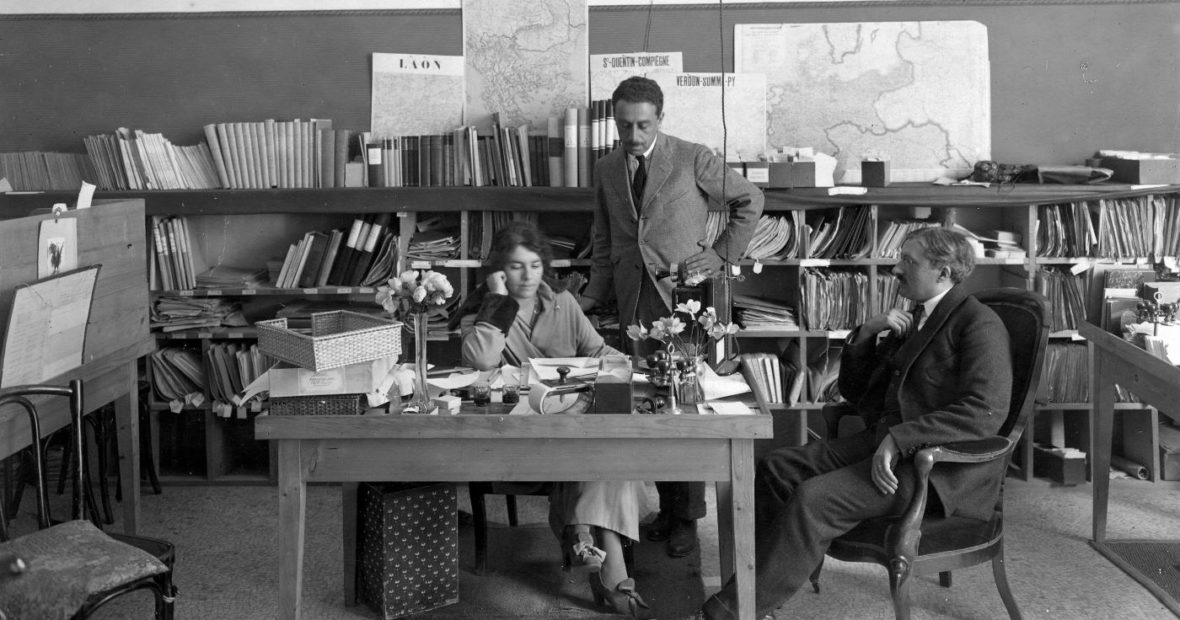

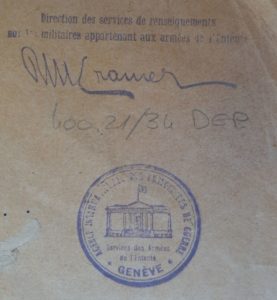

On August 15th, 1914, the ICRC opened an “International Agency for assistance to and information concerning prisoners of war”, tasked with centralizing and managing “all the information and donations intended for prisoners of war”.[9] A mere few days later, Renée-Marguerite resigned from her position at the University of Geneva and joined the newly founded Agency. There she worked among familiar faces, including many of her relatives. Together with Jacques Chenevière,[10] she became the director of the Département de l’Entente, the section of the Agency in charge of the Allied prisoners of war (POWs) detained in the territories of the Central Powers. Her work consisted of managing all the information related to this category of POWs, supervising and coordinating how that information was captured, filed and later shared with families. Highly invested in the Agency’s daily running, Renée-Marguerite did not hesitate to weigh in on the organization of its different tasks.

Years later, she would describe her work during the First World War in a short publication titled Organisation d’un bureau central de renseignements – today included in the ICRC library’s prisoners of war collection. This essay is an illuminating source of information on her work for the Agency, and the important lessons she drew from her experience. She warned that anticipating how a tracing agency would work was no easy task, and thus that being flexible and innovative was a must. Most importantly, she recommended making sure to have enough space to accommodate all the necessary services and staff. The International Prisoners of War Agency’s spectacular growth in 1914 had indeed forced it to move twice, to the Palais Eynard first, and later to the Rath Museum. Regarding the staff, she noted that if it can be “partly composed of volunteers”, technicians and collaborators with strong skills in historical methodology and classifying methods would be particularly valuable.[11] The work of the Agency was indeed divided in a series of specific tasks, each of them executed by specialized workers. This division of the work, she noted, improved both its rapidity and accuracy.[12]

Regarding budget issues, Renée-Marguerite Cramer recalled that “the Agency had always worked for free, but if it did not ask for any compensation for the provided services, it is obvious that it accepted even the smallest donations”.[13] To collect such donations, the Agency sold reports of visits of prisoner camps, postcards and stamps, and even organized theatrical performances.

The fact that other humanitarian organizations, like certain Red Cross National Societies, began doing similar humanitarian work during the war was a source of concern for the Agency. There was a clear risk that crucial information about the fate of POWs would be dispersed between different organizations and that the Agency’s central file would remain incomplete. In December 1916, Renée-Marguerite Cramer and Marguerite Gautier-Van Berchem went to Germany to convince the local Red Cross section based in Frankfurt to stop doing work that was already done in Geneva.[14] Tensions also arose with the American Red Cross, when it set in 1917 an Agency in charge of American prisoners in Bern. In her 1932 publication, Renée-Marguerite Cramer underlined the importance of having one central Agency.[15]

In March 1918, Renée-Marguerite announced she would resign from the Agency. When she eventually changed her mind, she insisted that the ICRC set up permanent delegations in the different belligerent countries and allowed the Agency’s heads of departments to sit in the Committee’s meetings. According to Cédric Cotter, by threatening to leave the Agency, Renée-Marguerite Cramer might have been trying to pressure the Committee into changing its ways.[16] In a note addressed to Frédéric Ferrière dated March 26th, 1918, she wondered :

“Will the International Committee take the opportunity to come back to this question to set up permanent delegations? Or, will Geneva stick to a policy of appeals and protests and leave to Copenhagen the initiative for this intervention and renounce the practical solutions whose efficiency has been demonstrated?” [17]

Humanitarian Diplomacy during the First World War

In the end of March 1917, Renée-Marguerite Cramer and Edmond Boissier, a member of the Committee, left Switzerland for Berlin, Copenhagen and Stockholm.[18] In Berlin, they met representatives of the Zentralnachweisenbureau, the section of the German War Ministry in charge of the information services, and of the German Red Cross Committee. Renée-Marguerite Cramer and Edmond Boissier aimed to see if the Agency could obtain more information about the fate of war victims, requesting for example that the lists of names of foreign soldiers killed on the battlefield be sent to Geneva. They also expressed their regret that the German War Ministry had forbidden German families from sending requests to organizations established in neutral countries, such as the Agency.

In early April, they arrived in Copenhagen where they met with Prince Waldemar of Denmark, the president of the Danish Red Cross.[19] The Danish Red Cross played at the time an essential role for the German and Austrian prisoners detained in Russia and for the Russians prisoners held captive in Germany. On this occasion, Renée-Marguerite Cramer and Edmond Boissier met different Danish delegates who had been able to visit POW camps in Russia. The conditions of detention there seemed to have improved since the first months of the war, but diseases spread among prisoners. The ICRC delegates also enquired about the conditions of detention of the 1’200 Austro-Germans prisoners held in Hald and the 1’200 Russians held in Horserod. Renée-Marguerite and Edmond were authorized to visit the camp of Horserod.[20]

They then pursued their journey towards Stockholm, where they were received by the Prince Charles of Sweden, the president of the Swedish Red Cross. They also met with the director of the Rockefeller Foundation’s Relief Commission to organize relief campaigns for the benefit of POWs.

During this journey, Renée-Marguerite Cramer and Edmond Boissier inquired about the conditions of detention of POWs. They were particularly alarmed by the risk of food shortage, as exports had plummeted. Overall, they deplored the terrible consequences of prolonged captivity on the prisoners’ physical and mental health. For this reason, they asked the belligerents to repatriate without any conditions any civilian or POW that had been detained for longer than two years.

On October 12th 1917, Renée-Marguerite Cramer went to Paris, where she struggled to be heard in official circles. She met with representatives of the different intelligence offices of the French Ministry of War and of the French, American and Romanian National Societies of the Red Cross. She successfully concluded an agreement with the French Government : they accepted to include in the lists sent to Geneva the cause of death of the German prisoners who had died in captivity. But she met greater resistance when trying to convince the French Government to quickly reach an agreement with Germany to exchange valid longtime prisoners: “We come to the conclusion that the French government abandons its children and accepts light-heartedly the sacrifice of the 130,000 men whose life, physical and mental life can be predicted with certainty after another winter in captivity”.[21]

In the end of 1917, Renée-Marguerite Cramer went to Bern, where the negotiations between France and Germany about the repatriation of prisoners were taking place. An agreement was finally reached on December 29th, 1917: French, Belgian and German soldiers and non-commissioned officers over 48 years old who had been detained for more than 18 months would be repatriated.[22]

Developing International Humanitarian Law after the First World War

The First Woman to Become a Member of the Committee

On June 1st, 1918, Edouard Naville recommended the appointment of Renée-Marguerite Cramer as a member of the International Committee “based on her qualifications and service”. He also added that a woman’s presence in the International Committee “would only serve to honor and strengthen it”.[23] ICRC president Gustave Ador supported Edouard Naville’s recommendation, “given the exceptional qualities of the candidate”.[24] Her undeniable intellectual qualities and her work for the Agency during the First World War were certainly strong arguments in favor of her nomination. If Gustave Ador did note that the decision to appoint a woman might surprise outside of the ICRC, objections to her candidacy did not focus on her gender at the time. The fact that access to the ICRC’ governing body was restricted to Swiss citizens, and more often than not to Genevans from a particular, privileged social class, had attracted some criticism. Since Renée-Marguerite was clearly a member of this Genevan ‘bourgeoisie’, her nomination would risk reopening this debate. The reaction of certain Red Cross National Societies, especially the American Red Cross, was also feared, as there was a history of tensions between them.[25] For those reasons, Renée-Marguerite’s nomination was slightly delayed. Finally, on November 27th, 1918, it was noted in the minutes of meetings of the Agency that “Miss Cramer had accepted to be appointed member of the International Committee”.[26]

In 1920, Renée-Marguerite married Edouard Frick, an ICRC delegate who was based in Eastern Europe. Later, she moved to Germany. Being away from Geneva made it difficult for her to take part in the activities of the ICRC. In December 1922, she resigned and was named an honorary member of the International Committee. Her work during the interwar period focused on the colossal task of improving the international legal protection of POWs and civilian internees.

A New Convention for Prisoners of War

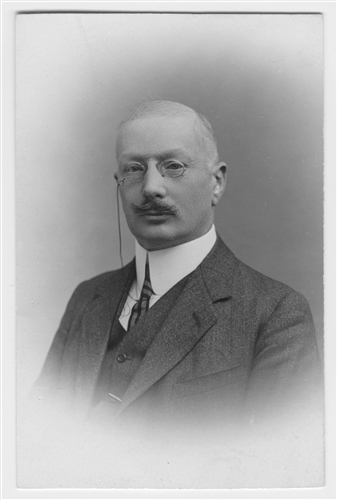

Portrait of Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer in 1929 (ICRC Library)

In the early 1920s, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer first turned her attention to the repatriation of people who had been displaced because of the war. Around 12 million people were in that situation, and their return represented a huge challenge both in terms of diplomacy and logistics. The repatriation of the POWs who had been detained in Siberia was a particularly thorny issue. The ICRC worked hand in hand at the time with Norwegian diplomat Fridtjof Nansen, who would later become the first High Commissioner for Refugees.

In May 1920, Renée-Marguerite published in the International Review of the Red Cross an account of their joint action for the repatriation of those former prisoners. She noted that the agreements related to the exchange of POWs between belligerents concluded in The Hague, Bern and Copenhagen were not comprehensive enough. She strongly advocated for belligerents to accept the principle of the repatriation of longtime POWs, even if they were not injured. Their return was often further delayed because negotiations on the issue of repatriation were conditioned on the conclusion of peace treaties between the belligerents. In her 1920 article, Renée-Marguerite recalled that, during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the ICRC had insisted that the repatriation of POWs of any nationality should not have to wait the conclusion of the Conference:

“We know how slow these negotiations are; they have not yet given any results regarding the Central Powers. For a long time, any attempt to get the question of prisoners of war to be dealt with separately remained unsuccessful because of these delays. The Treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain indeed provide that the repatriation of prisoners of war will take place as soon as possible after the entry into force of these treaties […]. Thus far, only the treaty with Germany is in force, therefore, according to the texts, only German prisoners of war can be repatriated.” [27]

In an article published in November 2018,[28] Neville Wylie and Lindsey Cameron argue that the experience of detention during the First World War lead to many changes in the law protecting POWs. Their status evolved: no longer simply “disarmed combatants”, they became “humanitarian subjects”. This was a very important evolution in the condition of POWs; it was finally acknowledged that the legal framework offered by previous conventions of international law remained too imprecise, leaving the door open to multiple interpretations. Issues such as the repatriation of POWs, the prevention of reprisals and the control of conditions of detention needed to be further discussed and codified.

This shift in prisoners’ perceived status and the questions arising were quite visible in Renée-Marguerite’s work. In fact, she was convinced of the need to “conclude a new Convention, ruling on the fate of soldiers and civilians captured at the start of or during hostilities”.[29] In the 1920s, the International Law Association and the ICRC each took the decision to draft texts that could become the basis of such a Convention, a code for the treatment of POWs and one for civilian detainees. Renée-Marguerite saw these drafts as partially flawed, “overly inspired by the conventions that were concluded during the war“. She notably argued that there was “no reason to apply different rules to military prisoners and civilian internees. Both of them, captured in the lines or in the enemy’s country, are interned in camps and their regime is similar”.[30] On the other hand, she deplored “the excessive wealth of details” with which these codes were drafted. In her view, the new Convention should be more broad and universal, anchoring principles that could serve as the basis for other special regulations.

Renée-Marguerite was one of the main authors of the draft document which would later become the 1929 Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Commenting on the adoption of this new Geneva Convention, she wrote in a letter to Gustave Ador that:

“It cannot be denied that, because of the length of the hostilities, the prisoners have become a political instrument (…), which is an infinitely regrettable fact. Let us hope that with the new Convention, thanks to the oversight and supervision of the neutrals and the possibility of the belligerent powers to hear each other out, misunderstandings will be avoided, and instructions given at the highest level will be carried out”. [31]

The Tokyo Project and the Protection of Civilians in Occupied Territories

In 1934, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer wrote that “due to an inexplicable lacuna in the law of war, there is no legal provision protecting civilians of belligerent citizenship when they are in an enemy territory”. The final act of the 1929 Diplomatic Conference had expressed the wish that “detailed studies should be undertaken in order to conclude an international convention concerning the condition and protection of civilians of enemy nationality who are in the territory of a belligerent or in an occupied territory”,[32] but had not included this category of war victims in the new Convention. Renée-Marguerite had experienced the consequences of this gap in the law during the First World War, as she had worked with the Dr. Frédéric Ferrière, the founder of the International Prisoners of War Agency’s service for civilian victims of the war.

Members of the international Red Cross and Red Crescent humanitarian network had already weighed in on this issue. At the 1921 International Conference of the Red Cross, participants had adopted a resolution that notably condemned hostage taking and the deportation without trial of civilians and affirmed their right to receive humanitarian assistance. In another resolution, participants of the 1925 International Conference established a series of principles related to the protection of civilians in enemy territory, notably arguing that they should benefit from the same conditions of treatment than POWs.[33]

In the early 1930s, the ICRC set up a commission to prepare a draft Convention concerning the protection of civilians.[34] This draft Convention – better known as ‘The Tokyo draft’ – was presented at the International Conference of the Red Cross in 1934.

Presenting this text, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer related the surprise of the assembly “when they realized that, if hostilities were to break out, civilians living in an enemy state would not benefit from any international legal protection but would fall at the mercy of the States on whose territory they were”.[35] She noted that the ICRC project was well received, immediately being accepted as a basis for future diplomatic negotiations. Bolstered by this support, the ICRC then contacted the Swiss Federal Government to convene a Diplomatic Conference similar to the one that had led to the adoption of the new Geneva Convention in 1929. Planned for the beginning of the year 1940, this Diplomatic Conference had to be cancelled when the Second World War broke out. Renée-Marguerite deeply regretted the failure of the international community to adopt a Convention protecting civilians. As the war raged on, she saw hundreds of thousands of people being displaced “just like in 1914, deprived of any international legal protection”.[36]

Returning to the Agency: Renée-Marguerite’s Humanitarian Work during WWII

In September 1939, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer was re-elected as a member of the Committee. Returning to Geneva, she got fully involved with the work of the ‘Central Agency for Prisoners of War’. At the beginning of the war, the ICRC reopened indeed its Agency for prisoners of war under this slightly changed name. The centralization of all information related to the fate of POWs in a tracing Agency located in a neutral country was now well accepted, as it was included in the provisions of the 1929 Geneva Convention. This Agency’s mission would be to act as an intermediary between the belligerents to advocate for the protection of POWs, and between imprisoned or missing soldiers and their families.

But the Convention also left some leeway to the Agency, as article 79 noted that such provisions “should not be interpreted as restricting the humanitarian activity of the International Committee of the Red Cross”. In April 1944, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer described a new service of the Agency in the article Au service des familles dispersées (Helping separated families). She wrote that they were receiving countless requests for information about missing relatives, a direct consequence of the estimated 40 million people displaced by the conflict.[37] In April 1944, the central file of dispersed families included about 94,000 files.

As the war raged on, Renée-Marguerite focused increasingly on the fate of civilian victims. She observed in 1943 that, when it came to citizens living in the territory of an enemy state, “the Tokyo project, although it had not been sanctioned by a diplomatic conference, had nevertheless facilitated the gradual adoption of customary law, which was now applied in a more or less uniform manner by all belligerent States”. [38] On the other hand, she noted that the populations of the occupied territories did not benefit from the same considerations; she condemned the generalization of methods of ‘total warfare’, such as deportations and hostage taking.

In 1942, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer tried to convince the Committee that it was necessary for the ICRC to take action in a strong manner in favor of those deported by the Nazi. Since November 1939, she had been in contact with the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, who wished to set up a tracing agency for the deportees and send them relief packages.[39] In February 1940, Renée-Marguerite tried to convince Max Huber, the president of the ICRC, to send Carl J. Burckhardt on a mission to Berlin to organize further humanitarian action for the internees of the concentration camps. Since they were presented as ‘political prisoners’, she noted that this was “obviously a very delicate question”, but that the ICRC had never renounced trying to bring at least material aid to political prisoners.[40]

In September 1941, news reached the ICRC that French POWs were deported to Mauthausen, where they would become “Schutzhäftlinge”. They then depended on the civil authorities and were subjected to a special regime. The news led Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer and Suzanne Ferrière to take a much closer look at this situation. At the end of April 1942, they wrote with the Dr. Alec Cramer a note proposing a series of measures to help the deportees, such as requesting to visit the camps and organizing relief operations with the help of Israeli organizations. Renée-Marguerite also put forward the idea of demanding for the deportees the right to send regular updates on their situation, an proposition that was unfortunately rejected.

On October 14th, 1942, finally, the members of the Committee debated the option of speaking publicly, as a last resort. Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Suzanne Ferrière, Lucie Odier, Renée Bordier, Edmond Boissier, Paul Des Gouttes, Dr. Alec Cramer, and the Swiss diplomat Georges Wagnière spoke in favor of a solemn public protest. But more Committee members opposed this public condemnation, which was thus abandoned, very much to the regret of Renée-Marguerite. At the beginning of 1943, with Marcel Junod, she continued to insist on the importance to try and get information on the fate of Jewish deportees, but this issue would remain unsolved until the end of war.

She persisted in her efforts. In November 1944, for example, she signed a request for information related to the deportees of Szeered and Marianka. All she received in return was an acknowledgment her message had been received. But information filtered through other channels. In 1944, she learned about the medical experiences perpetrated on Polish prisoners. Because it had been denied the permission to visit concentration camps, the ICRC had very limited possibilities to act. Renée-Marguerite was devastated. She wrote that “if nothing can be done, well, perhaps we should send these people something to end their lives; it might be more humane than giving them food”.[41]

After the war, most came to share Renée-Marguerite’s ardent support for a legal framework that sought to protect the civilians displaced and interned during the conflict. The deportations and the terrible suffering endured by the civilian victims of the Second World War would be the determining factor leading to the adoption in 1949 of the Geneva Convention relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war.

The Adoption of the Fourth Geneva Convention

Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer resigned in November 1946, returning to her status as an honorary member of the Committee.[42] She still took part in the preparations leading to the drafting and later adoption of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. In February 1947, she submitted the text of a draft Convention. Remaining faithful to the 1934 Tokyo project, she recommended merging the Conventions protecting soldiers and civilians. It was finally decided that her text would not be the one distributed to the experts. Instead, her version was published in March 1947 in the International Review of the Red Cross. She remained involved in the process leading to the adoption of the Conventions, pushing the ICRC to hasten the procedure. If the Conventions finally adopted were not based on her draft, it is undeniable that they represented the conclusion of a long process in which she played a crucial role.

During her lifetime, Renée-Marguerite Cramer witnessed a dramatic evolution in warfare. If civilian casualties had been much lower than military ones in the First World War, this proportion had flipped by the end of the Second World War. Civilians were becoming the first victims of armed conflicts.

At the end of the First World War already, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer had become aware of the humanitarian implications of the evolution of warfare. In her research, she moved away from the topics of predilection of the 1920s – the question of disarmament and the use of chemical and bacteriological weapons – to focus on the development of an international legal basis for the protection of civilians.

Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer passed away on October 22, 1963.[43] She left behind the memory of a woman confident in the value of the humanitarian ideal,[44] and a tenacious and determined worker who was inventive and innovative in the way she thought about international humanitarian law. She believed that the ICRC’s activities were not limited by past Conventions and resolutions, but that it had both “the right and the duty to innovate whenever the laws of humanity require it.” [45]

Looking for more? Find here all the library’s holdings related to Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer.

Bibliography

Contributions of Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer to the International Review of the Red Cross and other writings held in the ICRC library

- Renée-Marguerite Cramer, « La tâche de la prochaine conférence internationale des Croix-Rouges », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 4, avril 1919, p. 403-409

- Renée-Marguerite Cramer, « De l’activité des Croix-Rouges en temps de paix », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 7, juillet 1919, p. 755-787

- Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre centraux en Russie et en Sibérie et des prisonniers de guerre russes en Allemagne », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 2, no. 17, mai 1920, p. 526-556

- Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « La Xe Conférence internationale de la Croix-Rouge », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 23, novembre 1920, p. 1212-1224

- Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « A propos des projets de conventions internationales réglant le sort des prisonniers », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 74, février 1925, p. 73-84

- Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge et les Conventions internationales pour les prisonniers de guerre et les civils », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 293, mai 1943, p. 386-402 ( English version in 1945)

- Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Au service des familles dispersées », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 304, avril 1944, p. 307-317 ( german version)

- Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Le rapatriement des prisonniers du front oriental, après la guerre de 1914 – 1918 (1919 – 1922) », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 309, septembre 1944, p. 700-727 (version anglaise)

- Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Organisation d’un bureau central de renseignements, Genève : CICR, 1932

- Ferrière Adolphe, Le docteur Frédéric Ferrière : son action à la Croix-Rouge internationale en faveur des civils victimes de la guerre, Genève : Suzerenne, 1948 (Introduction written by Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer)

Primary sources

- Les procès-verbaux de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre (AIPG), édités et annotés par Daniel Palmieri, Genève : CICR, octobre 2014

- Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, Nouvelles de l’Agence Internationale des Prisonniers de Guerre, Genève : CICR, 1916-1918

- Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, Nouvelles de l’Agence Centrale des Prisonniers de Guerre, Genève : CICR, 1940-1947

Biographies and secondary sources

- Cédric Cotter, (S’) aider pour survivre : action humanitaire et neutralité Suisse pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale, Chêne-Bourg : Georg, 2017, p. 330-331.

- Jean-Claude Favez, Une mission impossible ? Le CICR, les déportations et les camps de concentration nazis, Lausanne : Payot, 1988

- Irène Herrmann, « Marguerite Cramer : « appréciée même des antiféministes » », in Action humanitaire et quête de la paix : le prix Nobel de la paix décerné au CICR pendant la Grande Guerre, Genève, Fondation Gustave Ador, 2019.

- Daniel Palmieri, « Marguerite Frick-Cramer : Genève, 1887-1963 », in Les femmes dans la mémoire de Genève : du XVe au XXe siècle, Genève : S. Hurter, 2005, p. 182-183.

- Daniel Palmieri, « Guerre, humanité, féminité : le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge et les femmes », in Femmes et relations internationales au XXe siècles, Paris : Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2006, p. 189-196.

[1] Irène Herrmann, « Marguerite Cramer : « appréciée même des antiféministes » », in Action humanitaire et quête de la paix : le prix Nobel de la paix décerné au CICR pendant la Grande Guerre, Genève, Fondation Gustave Ador, 2019, p. 155.

[2] Daniel Palmieri, « Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer : Genève, 1887-1963 », in Les femmes dans la mémoire de Genève : du XVe au XXe siècle, Genève : S. Hurter, 2005, p. 182.

[3] Natalia Tikhonov Sigrist, « Les femmes et l’université en France, 1860-1914 : pour une historiographie comparée », in Histoire de l’éducation, no 122, 2009, p. 54.

[4] « Nos avocates », in Journal de Genève, Genève, Mercredi 27 juillet 1910, p. 4.

[5] « Trente ans au service de la Croix-Rouge internationale », in Journal de Genève, Mardi 15 août 1944, p. 5.

[6] The Prix Ador, awarded by the University of Geneva, rewards a historical dissertation.

[7] Daniel Palmieri, « Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer : Genève, 1887-1963 », in Les femmes dans la mémoire de Genève : du XVe au XXe siècle, Genève : S. Hurter, 2005, p. 182.

[8] Irène Herrmann, « Marguerite Cramer : « appréciée même des antiféministes » », in Action humanitaire et quête de la paix : le prix Nobel de la paix décerné au CICR pendant la Grande Guerre, Genève, Fondation Gustave Ador, 2019, p. 155.

[9] Circulaires 159 et 160, du 15 et 27 août 1914, Genève, CICR.

[10] Jacques Chenevière, Retours et images, Lausanne, Rencontre, 1966, p. 174.

[11] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Organisation d’un bureau central de renseignements, Genève : CICR, 1932, p.14.

[12] Ibid., p.16.

[13] Ibid., p.81.

[14] Quoted from Cédric Cotter, (S’) aider pour survivre : action humanitaire et neutralité Suisse pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale, Chêne-Bourg : Georg, 2017, p. 482.

[15] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Organisation d’un bureau central de renseignements, Genève : CICR, 1932, p.10.

[16] Cédric Cotter, (S’) aider pour survivre : action humanitaire et neutralité Suisse pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale, Chêne-Bourg : Georg, 2017, p. 331.

[17] Note from Marguerite Cramer to Frédéric Ferrière, 26 March 1918, ACICR C G1 A 19-33.

[18] « Mission de M. Edmond Boissier et de Mlle Cramer à Berlin, Copenhague et Stockholm avril 1917 », in Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no 191, juillet 1917, p. 236.

[19] Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, Nouvelles de l’Agence Internationale des Prisonniers de Guerre, Genève : CICR, 1917, p. 117.

[20] « Mission de M. Edmond Boissier et de Mlle Cramer à Berlin, Copenhague et Stockholm avril 1917 », in Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no 191, juillet 1917, p. 242.

[21] Quoted from Cédric Cotter, (S’) aider pour survivre : action humanitaire et neutralité Suisse pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale, Chêne-Bourg : Georg, 2017, p. 141.

[22] Les procès-verbaux de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre (AIPG), édités et annotés par Daniel Palmieri, Genève : CICR, octobre 2014, p. 210.

[23] Ibid., p. 241.

[24] Ibid., p. 243.

[25] Idem.

[26] Quoted from Irène Herrmann, « Marguerite Cramer : « appréciée même des antiféministes » », in Action humanitaire et quête de la paix : le prix Nobel de la paix décerné au CICR pendant la Grande Guerre, Genève, Fondation Gustave Ador, 2019, p. 154.

[27] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre centraux en Russie et en Sibérie et des prisonniers de guerre russes en Allemagne », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 2, no. 17, mai 1920, p. 529.

[28] Neville Wylie and Lindsey Cameron, « The Impact of World War I on the law governing the treatment of prisoners of war and the making of a humanitarian subject », in The European Journal of International Law, Vol. 29, no. 4, 2018.

[29] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « A propos des projets de conventions internationales réglant le sort des prisonniers », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 74, février 1925, p. 74.

[30] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « A propos des projets de conventions internationales réglant le sort des prisonniers », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 74, février 1925, p. 76.

[31] Quoted from Neville Wylie and Lindsey Cameron, “The impact of World War I on the law governing the treatment of prisoners of war and the making of a humanitarian subject”, in European journal of international law, Vol. 29, no. 4, November 2018, p. 1327-1350.

[32] CICR, Projet de convention concernant la condition et la protection des civils de nationalité ennemie qui se trouvent sur le territoire d’un belligérant ou sur un territoire occupé par lui (point 9 de l’ordre du jour), Genève : CICR, 1934, p. 2.

[33] CICR, Projet de convention concernant la condition et la protection des civils de nationalité ennemie qui se trouvent sur le territoire d’un belligérant ou sur un territoire occupé par lui (point 9 de l’ordre du jour), Genève : CICR, 1934.

[34] This Civilians’ commission becomes a Commission for political detainees in March 1935. Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer remained a member. See Jean-Claude Favez, Une mission impossible ? Le CICR, les déportations et les camps de concentration nazis, Lausanne : Payot, 1988, p. 57.

[35] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge et les Conventions internationales pour les prisonniers de guerre et les civils », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 293, mai 1943, p. 27.

[36] Idem.

[37] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Au service des familles dispersées », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 304, avril 1944, p. 310.

[38] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, « Le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge et les Conventions internationales pour les prisonniers de guerre et les civils », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No 293, mai 1943, p. 29.

[39] Quoted from Jean-Claude Favez, Une mission impossible ? Le CICR, les déportations et les camps de concentration nazis, Lausanne : Payot, 1988, p. 217.

[40] Ibid., p. 219.

[41] Ibid., p. 104.

[42] On this occasion, the International Review of the Red Cross published a bibliography of all Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer’s contributions: « Comité », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no 335, novembre 1946, p. 964-965.

[43] « Nécrologie », in Gazette de Lausanne, Lausanne, 23 octobre 1963.

[44] « † Mme R.-M. Frick-Cramer », in Revue Internationale De La Croix-Rouge, no 539, novembre 1963, p. 573-574.

[45] Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Organisation d’un bureau central de renseignements, Genève : CICR, 1932, p. 83.

thank you very much for ths most interestiing & important account of an exceptional woman, probably first woman at ICRC and first to hold a Diplomatic Paaport in Switzerland.

Most appropriate to mention her & describe it so carefully: not only at women’s day but for all of us

Thank you & best wishes

JK