In any given contemporary conflict setting, there are a range of life-changing questions – and digital dilemmas – that people face, online, on a regular basis. Is the rumour on Facebook about an imminent bombardment true? Should we get out of the city to be safe? What about that YouTube video of snipers shooting at civilians – is it real? Can we trust the advice on this WhatsApp group managed by political opponents to the government? What about this NGO offering us ‘safe’ internet access to connect to our family and friends – is it true that they are giving away information about who we are? They are calling for people to register with them, but is this just a trap? And is it true these foreigners are bringing COVID-19 to our communities?

The ‘fog of information’ is thickening

The ‘fog of war’ originally refers to the difficulty for combatants to maintain a clear picture and understanding of their own capability and situation – and that of their adversary – during armed conflict operations. Today, with the ubiquity of digital technologies and communication systems in humanitarian settings, the ‘fog of war’ is evolving into a ‘fog of information’ for affected populations. This 21st century version brings with it new layers of complexity, uncertainty, and risks for populations and communities affected by conflict and violence.

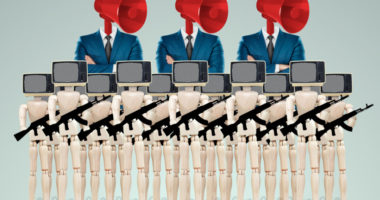

Misinformation, disinformation and hate speech are not new. Information operations have long been part and parcel of armed conflicts. What has changed is how they can be created, spread and consumed not only by armed actors but also by individuals, with a speed and reach that can reverberate around the world. The digital forms of MDH seem to have outsized and outpaced our abilities to apprehend them. In this digital information environment, it is becoming increasingly difficult to discern truth from lies; in situations of conflict and violence, the choices made on the basis of this information are a matter of life and death.

A growing blind spot

In recent months, we’ve seen a significant amount of attention and research on the impact of the ‘infodemic’ and ‘information apocalypse’ affecting our global societies and fundamental rights and freedoms. Hundreds of initiatives, webinars, and guidelines on MDH have burgeoned. This is highly welcome, because MDH can weaken the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, fuel mistrust in election processes and public institutions, destabilize financial systems and pressure social fabrics, all with a negative impact on how we interact with and care for one another. It is a very real cause for concern.

However, we’ve also noted that the focus of those conversations remains by and large on what is happening in ‘democratic’ or ‘developed’ societies. It is not on what the information disorder is doing to the ‘Majority World’ or to people affected by war and violence. Yet, this is exactly where systemic, collective and individual resilience to these risks and threats are the lowest, and where the likelihood and potential for devastating consequences is the highest.

The truth is that when it comes to conflict-affected contexts, we have a blind spot. The humanitarian consequences of MDH seem to be there. Yet, it is extremely complex to establish clear causal links between these online phenomena and the violence unfolding in real life. What we can see happening on the ground – from Myanmar to Ethiopia, Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh – is not reassuring. But it is likely to be only the tip of the iceberg.

In 2019, the ICRC conducted field research in Sri Lanka and Ethiopia to understand the key humanitarian operational challenges with regards to MDH. What emerged is that: one, the rapid evolution of digital information technologies is turning MDH into an exacerbating and accelerating driver of conflict dynamics, violence, and harm which can have important implications for humanitarian needs and response; and two, there is a research and evidence-knowledge gap as to what these implications are, how far they affect populations in conflict affected places, and what are the possible options to address them effectively.

Since this study, the COVID-19 pandemic has fueled health misinformation, putting trust in healthcare providers such as MSF into the spotlight. In conflict contexts, where a lack of trust in the authorities sometimes exists, suspicion of the motives of healthcare providers can serve as the spark to incite attacks on healthcare workers and facilities, as we saw in 2020 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Rumours and misinformation circulating on the internet are bringing to the fore anxieties about the political motivation behind vaccinations, as well as the security and efficacy of vaccines. This can undermine the health of people living in conflict zones, who already find accessing healthcare a challenge.

In contexts where hate speech thrives, sensitive medical information stored online can be hacked or leaked by malicious actors to further stigmatize and discriminate against vulnerable patients. Healthcare workers and organizations working in conflict zones need to improve their protection against data leaks and hacks and to ensure good cybersecurity. Effective online health messaging should be complemented with community engagement initiatives to address people’s fears.

People affected by conflict deserve to be able to access reliable information and to be able to participate in conversations on social media without being attacked.

Getting ahead of the curve

What is concerning is that these phenomena are only likely to increase and accelerate, at least in the near future. Artificial Intelligence and geostrategic, political, and economic interests will continue to fuel MDH, and it is unclear whether emerging solutions will be scalable or transposable to all contexts. But instead of wringing our hands about what will happen if nothing is done, we need to take action. As humanitarian actors focusing on the protection of the life and dignity of populations affected by conflict, we need to raise awareness and find ways to mitigate the worst consequences for affected people. But we can’t do this on our own.

So here is our call to action:

- We need to ensure that the broader conversation on the ‘information disorder’ or MDH includes a conflict-setting dimension – these are the societies and communities most at risk. If these specific vulnerabilities are not integrated and addressed, global efforts will remain incomplete and leave many vulnerable people behind. More research and evidence is needed on the humanitarian consequences of MDH.

- We need to mobilize the humanitarian sector to engage on these issues, since they are increasingly relevant to our missions, the environments we work in and our ability to make a positive difference for the lives of people affected by conflict and violence. We need to protect humanitarian action from the conflict dynamics brought by online MDH. We need to promote the perspectives of affected people into these conversations and find ways to protect an online humanitarian space.

- We need to ensure that other stakeholders – from private tech companies, to donors, governments and civil society actors – integrate a conflict sensitivity lens into their work, research and advocacy. Humanitarian actors may not have the required skills or resources to solve these complex problems, but we are well placed to testify and bring attention to what is happening on the ground. There may be also a need to change the methods and assumptions at play in those debates. The presumption that, in some circumstances, digital technologies are intrinsically good for affected populations, and that we can just mitigate some of the risks they may bring, may need to be revisited.

We are ready to do our part – to try new approaches in our operations, to conduct more research, and to engage in the dialogue with all stakeholders on these issues. Will you join us?

See also

- Rachel Xu, You can’t handle the truth: misinformation and humanitarian action, January 15, 2021

- Massimo Marelli & Martin Schüepp, Hacking humanitarians: operational dialogue and cyberspace, June 4, 2020

- Massimo Marelli & Adrian Perrig, Hacking humanitarians: mapping the cyber environment and threat landscape, May 7, 2020

- Massimo Marelli, Hacking Humanitarians: moving towards a humanitarian cybersecurity strategy, January 16, 2020

Comments