There is today an idea of a single humanity, with each member equally valued, and a global legal framework exists to prevent needless human suffering, including in war. Dehumanization arises as the negation of a common, positive, and mutually supportive humanity, though there is no single definition, and it certainly predates its opposite. Research indicates that dehumanization increases the risk of conflict and violence, increases the risk of abuses therein, and makes it harder to resolve conflict.

In this post – an overview of a forthcoming article written in her personal capacity – Natalie Deffenbaugh posits mirror definitions of humanity and dehumanization and what they mean, especially in relation to conflict and violence. She looks at why and how dehumanization happens and the real-world harm that can result when espoused or tacitly condoned by those holding power. She closes with an overview of how humanity, in global legal frameworks and as a Fundamental Principle, can curb and push back against some of the worst that dehumanization can do.

Editor’s note: This article represents the authors’ personal views and does not necessarily reflect positions of the ICRC. Comprehensive references for this research are available in the article published in the International Review of the Red Cross, “De-dehumanization: Practicing humanity”.

Murder, enslavement, rape, torture, genocide: among the worst things that human beings do to other human beings, these acts are not new. They’re often linked with war, and they’re more likely to go unchecked when perpetrated under the aegis of people in power. And they often accompany an idea that the targets are not fully human. Dehumanization is real: can the principle of humanity do something about it?

Understanding humanity and dehumanization

Though dehumanization is arguably older, let’s nevertheless start by looking at “humanity.” Building on the reflections of Dunant,[1] Pictet, and others (e.g. Coupland, Fast, Slim, Kronfeldner[2]) I suggest a practical concept of human/humanity; the principle of humanity then enjoins us to realize that concept and produce humane treatment, including through international norms. For the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, this practice of humanity is a Fundamental Principle calling for action to uphold the human being’s fundamental worth. It is the driving force for everything that humanitarians in the Movement, and most of those outside it, do.

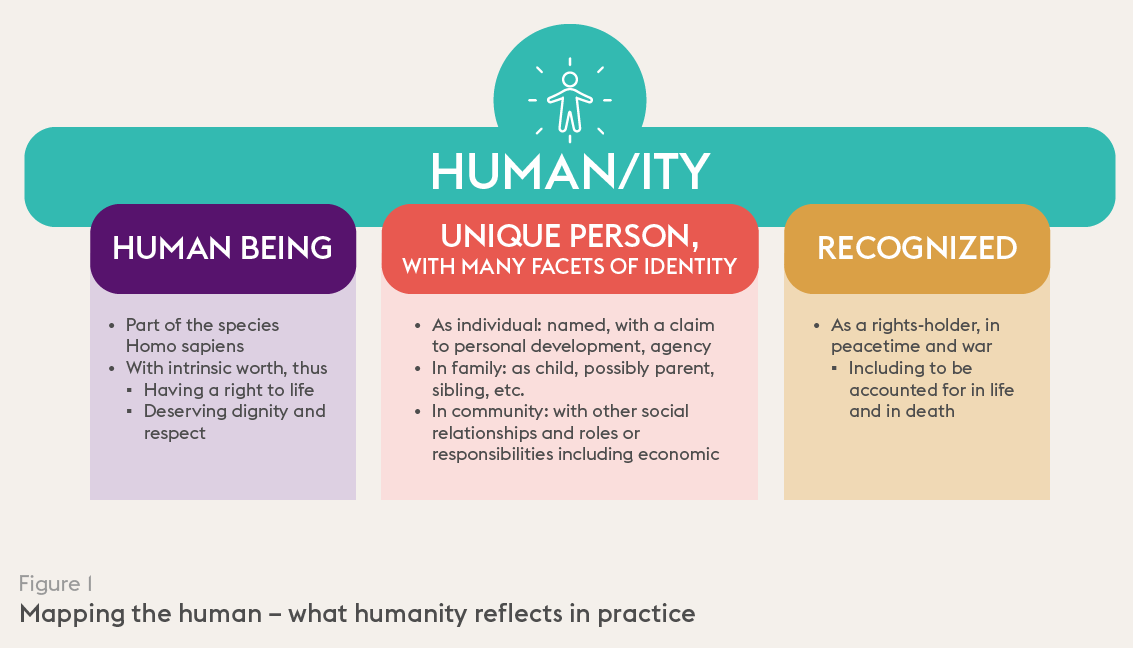

My concept of humanity in practice contains three elements (Figure 1) that together show how humanity should be practiced and can be reinforced:

- Belonging to the human species, reflecting humanity-humankind;

- Being a unique and multi-faceted individual, reflecting humanity-sentiment and an impulse of active goodwill towards others;

- Having affirmed standing within the rules that divide acceptable from abhorrent actions.

Figure 1

If the last element especially seems too conceptual, remember that having a human body, even one that eloquently expresses its personhood, is often not enough to be treated as human today. Such recognition increasingly depends on a record external to the person that says so – affirming or denying the person’s right to have rights. Without it, the person’s full humanity is suddenly suspect.

Think of children and others whose birth was not registered or who lost papers in the chaos of conflict and flight; people whose documentary identities are not or no longer accepted by the authority at hand; families of missing people.

The increasing digitalization of birth registries, immigration records, and identity documents makes things even more complicated. Even physical documentation could be denied or its validity questioned if it doesn’t match up with a digital database. While biometric IDs might solve that problem (while presenting other challenges), an authority still has to issue the document – that is, grant the status.

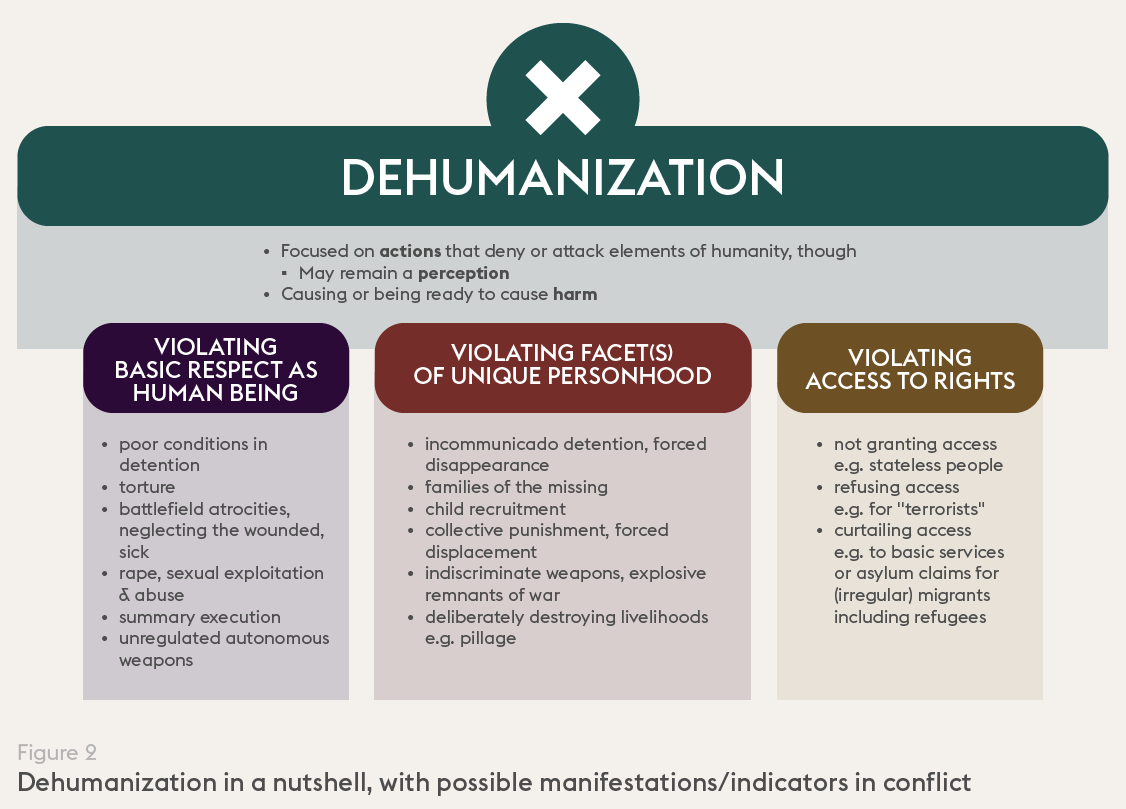

Which brings us to “dehumanization”. While there is no single understanding,[3] I suggest a practical definition suited to the situations of conflict and violence where the ICRC works: perceiving or acting as if someone is less than human, thereby causing or being more likely to inflict harm[4] (Figure 2).

Dehumanization violates one or more elements of humanity (above), in line with three useful concepts from the literature:

- Denying that someone else belong to the same human group as oneself;

- Ignoring and/or undermining that person’s unique identity;

- Violating her legitimate interests.

Figure 2

Researchers also describe dehumanized people being re-classified as animals, objects, or machines. In this conflict-centred discussion, I see these as methods of dehumanization, with the first two most relevant for people being targeted for harm.

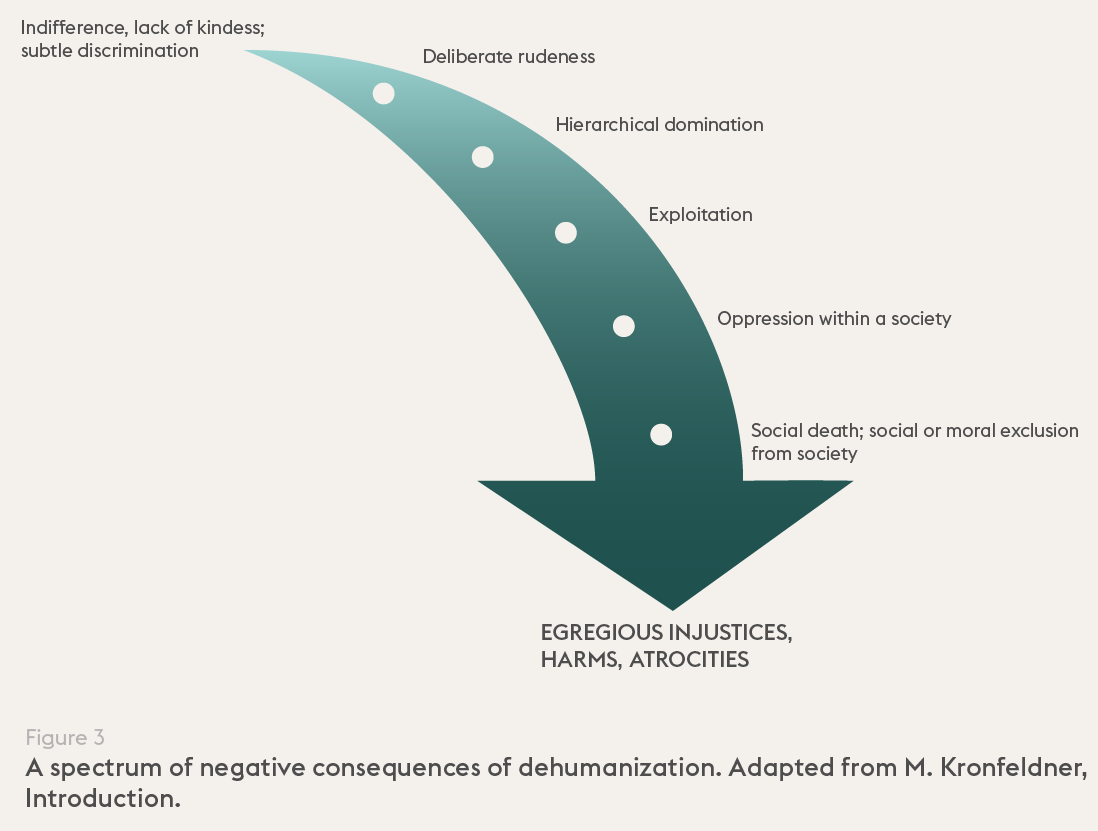

Because dehumanization causes real-world harm (Figure 3), blatant dehumanization can be measured, notably using the “Ascent” scale. Perceiving other people as less than human is robustly associated with direct violence; increasing support for conflict, violence, torture or retribution; and less support for helping behaviours, intergroup forgiveness and reconciliation (see also ICRC). Indeed, lowering or removing inhibitions that normally keep humans from harming each other, even to the point of making their mistreatment a moral duty, can be considered a hallmark of dehumanization (e.g. Giner-Sorolla, Leidner and Castano, Bruneau and Kteily, Kteily, Hodson and Bruneau, Castano, Muñoz-Rojas and Čehajić-Clancy).

Figure 3

Dehumanization: mechanisms and responsibility

Dehumanizers generally construct and then perceive in the dehumanized a threat, which allows the dehumanizers to see themselves as victims. Also linked is a desire for prediction and control, while a common thread of fear helps explain the power of dehumanizing narratives.

Because of authorities’ power and influence on systems and thinking, it is particularly concerning when they are involved. Dehumanization might arise or persist insidiously, but if people in power overtly or even “just” tacitly encourage dehumanization, the effects can be devastating.

Overt efforts

How does it work? Creating physical or psychological distance between the aggressors and the future victims is key. For example, long-range weapons relieve the perpetrator from sights, sounds, and other physical sensations that could hold them back.

Psychological distance is at work when ethnic identity or strong religious conviction drive dehumanization, but military training gives a more prosaic example.[5] By dehumanizing prospective targets, drill in particular seeks to protect personnel from moral injury when applying force – under orders, in combat. Such training is not bad per se, but the practice can be taken too far.

Language equating human beings with creatures that disgust or frighten is present in all clear instances of dehumanization and helps create psychological distance. Examples from across the globe include people being equated to microbes, bacteria, disease-carrying rats, worms, parasites, cockroaches, snakes, genetically deformed material and vermin to be annihilated, dogs, pigs, and maggots.

Meanwhile, “enemy” becomes a shortcut for the objectified opponent in battle and carries those overtones into more common use. Terms like “infidel”, “illegal migrant” and especially “terrorist” have come to signify beings who are not afforded full humanity. Such language is at least a warning of further harm to come.

In conflict, deliberate “information operations” are often seen as important complements to or foundations for fighting in other arenas. Like many humanitarians, I am concerned about misinformation, disinformation and hate speech (MDH) precisely because of how they risk undermining the humanity of people affected by conflict and violence.

Hate speech seems particularly likely to dehumanize by creating an enemy in everyday life, usually exploiting built-in or even long-dormant perceptions and biases in the cultural context and finding fertile ground in communities under stress. Messages from official channels will inevitably carry weight, the more so if authorities block alternate narratives, for example through internet shut-downs.

Laws are also an effective way to deny people’s full humanity. Dehumanizing legal frameworks carry over into administrative systems, affecting recognition of marriage, transfer of citizenship to children, or access to jobs.

What appears to be deliberate (mis)interpretation of otherwise sound frameworks can also dehumanize people, justifying acts that violate international humanitarian law (IHL). Arbitrary detention and collective punishment, which ground retribution in someone’s association with a group rather than her individual actions, cross a similar line.

Tacit encouragement

Regardless of the source, with today’s digital information and communication technologies dehumanizing content is amplified, propagates more quickly, reaches a wider audience, encounters less resistance, and is harder to trace than in the past.

If leaders don’t counter others’ dehumanizing efforts – e.g. if they tolerate sources of MDH, which tend to be stronger in places where internal political, religious or ethnic tensions are high – or if they seek to distance themselves through proxies, they implicitly convey that those efforts are acceptable, even correct.

Curbing dehumanization

So what do we do? Treat people as people, heal their wounds and restore their dignity: in short, act as the principle of humanity enjoins. This is a long and hard but not hopeless task.

Legal frameworks

Laws have force, and IHL exists to make the violence and horror of war less violent and horrible – to defuse the causal chains that dehumanization sets off and which can fuel it further. Humanity in IHL affirms our fundamental similarities and common interests. As the Geneva Conventions turn 75, we humans are reminded that we haven’t achieved our vision – yet: humanity in IHL also requires constant effort to do better.

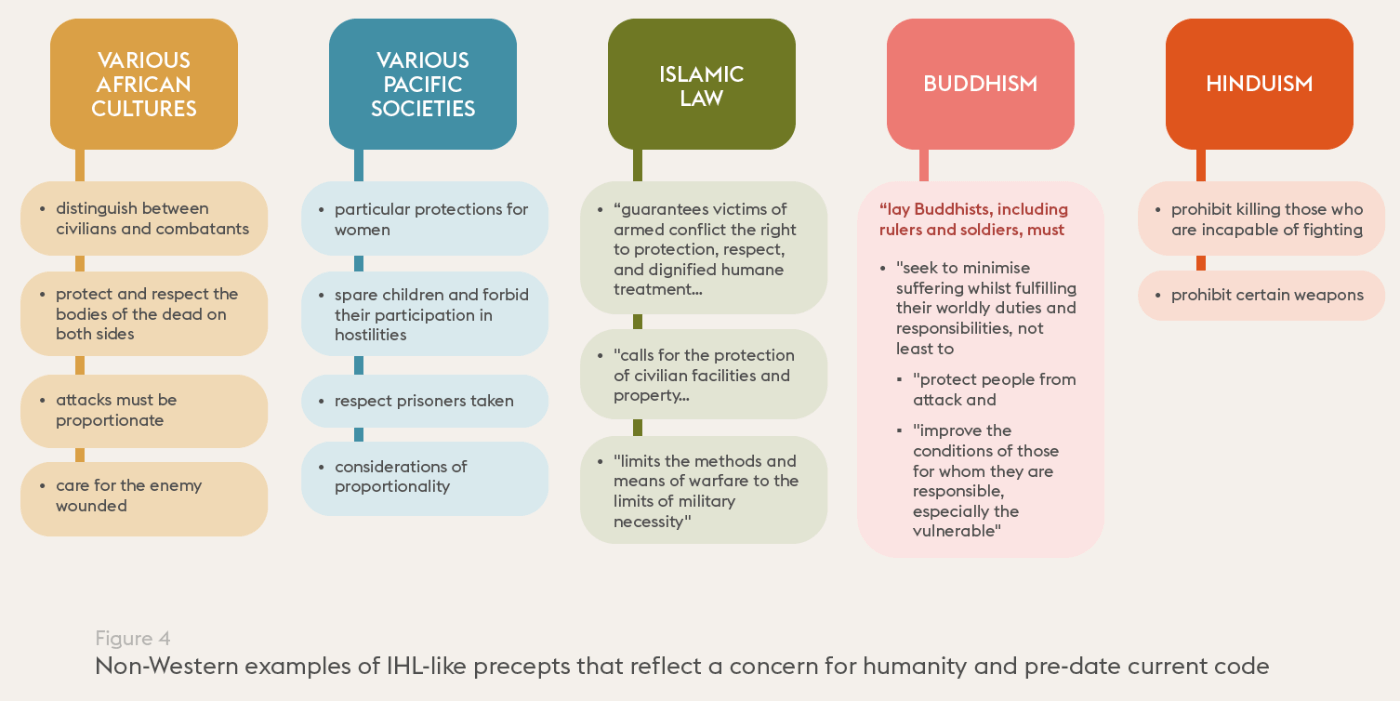

And we can. In the historical dialectic between harm caused and the setting of norms and formal standards to restrain that harm, conflict has seen notable progress. Long before today’s universally-adopted conventions, diverse cultures spanning millennia have promoted behaviours in war that uphold at least some aspects of humanity[6] (Figure 4).

Moreover, the overarching references to humanity in international law today[7] transcend any specific article to affirm recognition of the human by default, closing loopholes for those who might wish to follow only the letter of the law, and thus countering dehumanization in war.

Figure 4

The ICRC and the Movement

The core Movement principle of humanity spurs action to realize the idea of intrinsically valuable, unique, and formally recognized human beings. Closely linked is impartiality, reinforcing that only suffering and need can possibly justify treating a person or group differently from any other. From these, humane treatment will result – necessarily the opposite of dehumanization.

For the ICRC, this means being an independent observer to the application of IHL – the discreet but pointed gadfly to parties to conflict who might (conveniently) forget their obligations. In various places, war surgeons treat wounded human bodies; delegates visiting prisoners of war advocate for their dignity in daily life; the Central Tracing Agency keeps families connected even across front lines.

The ICRC has also long seen the increasingly administrative aspect of humanity and responded accordingly: Red Cross Messages can exchange identity documents alongside family news. And nobody seeking the ICRC’s help need prove their identity beyond that of a human being in need.

Consistent with the humanity principle, the ICRC encourages acts that go beyond the letter of current law if they will forestall (further) suffering and dehumanization – for example with respect to developments in autonomous weapons.

National Societies of the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement also play an important role in upholding humanity, especially when conflict is at their front door but even if it only seems hypothetical.

Rooted in their communities, National Societies, and their Federation, have the opportunity to use the principles of humanity and impartiality against dehumanization outside of conflict, too. This includes:

- Assisting and protecting human beings who have been treated as goods;

- Countering violence against women and girls, who have been dehumanized in various ways across cultures and millennia;

- Preventing and responding to violence against sexual and gender minorities, who face discrimination and have even been targeted for extermination;

- Promoting the dignity and inclusion of people with disabilities, who have also been targets of extermination and are still regularly excluded from inaccessible public spaces;

- Addressing systemic racism notably against irregular migrants – who are people, not a menacing “wave” or “flood”.

Humanitarians aren’t immune from dehumanization, though. As humans, we all come from societies with various forms and degrees of insidious racism and sexism; we are often psychologically or physically distanced from the people we serve; and it’s common to label people –with administrative codes or as “victims”. The very project of humanitarian action may risk perpetuating dehumanization,[8] including through the power differentials and value judgements inherent in the saving of lives: between humanitarians and “beneficiaries,” between international and local humanitarian workers.[9]

As it should for any human being, the spectre of dehumanization challenges humanitarians to review our actions, practicing the principle to see and respond to the entirety of someone’s humanity – the whole person behind the label, number, or screen. As power differentials will never disappear entirely from human interactions, we must identify where they lie and actively limit their effects. And we must staunchly reject any argument that someone’s humanity can ever truly be taken away.

Conclusion

Countering dehumanization hasn’t gotten easier in the last quarter century. People may have to “pay” for life’s essentials with personal information; digital platforms magnify MDH to pandemic proportions even as they cloud authorities’ responsibility; emotionally inert and potentially opaque algorithms are increasingly influencing decisions on who lives or dies on the battlefield. If dehumanization boils over into conflict, horrific suffering can echo through the generations.

Yet all is not lost. Today’s challenges don’t mean that the principle of humanity is outdated or ineffective: on the contrary. The ICRC, the rest of the Movement, and other humanitarians use it daily to contest and refute dehumanization on many fronts.

This is feasible because dehumanization is shaped by history, culture, social norms, and psychology – making it changeable over time and in different locations. People are resilient – and harm can be averted if there is honesty about what’s coming, and those in power decide to act.

As always, the main responsibility lies with those in authority – states, and armed actors in situations of conflict and violence – to respect and ensure respect for the international laws and standards they have set for themselves. Authorities’ practice has improved how human beings treat each other over time. Reinforcing that practice can keep dehumanization at bay: this is the true power of humanity.

References

[1] Henry Dunant, Un souvenir de Solferino, Institut Henry-Dunant and Slatkine Reprints, Geneva, 1980.

[2] M. Kronfeldner, “Preface”, “Introduction” in Maria Kronfeldner (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., Routledge, Abingdon, 2021.

[3] See for example: David Livingstone Smith, Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2021; chapters by L. Corrias, S. Fiske, N. Haslam, S. Heinämaa and J. Jardine, L. Kontler, E. Machery, and M. Mikkola, in Maria Kronfeldner (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., Routledge, Abingdon, 2021.

[4] Many discussions of dehumanization go well beyond conflict, exploring entrenched societal attitudes and norms. One can even conclude that any person not enjoying the full range of human rights is dehumanized. Conflict magnifies such harms. While they aren’t the focus here, I don’t wish to minimize the suffering that less extreme effects of dehumanization cause for millions whose humanity is violated, including by blocking full access to rights.

[5] See for example Paul Roscoe, “Intelligence, Coalitional Killing, and the Antecedents of War”, American Anthropologist, Vol. 109, No. 3, 2007; Dave Grossman, On Killing, Back Bay Books, Boston, MA, 1995.

[6] ICRC, “African Values in War: A Tool on Traditional Customs and IHL”, 2021; ICRC, “Under the Protection of the Palm”, 2009; ICRC, “Islamic Law and International Humanitarian Law: Common principles of the two legal systems”, 2020; Andrew Bartles-Smith et al., “Reducing Suffering During Conflict: The Interface Between Buddhism And (sic) International Humanitarian Law”, Contemporary Buddhism, Vol. 21, Nos. 1-2, 2020; Kjetil Mujezinović Larsen, Camilla Guldahl Cooper and Gro Nystuen (eds.), “Introduction by the editors: is there a ‘principle of humanity’ in international humanitarian law?”, in Searching for a ‘Principle of Humanity’ in International Humanitarian Law, Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 3. Further, “[p]rinciples of a humanitarian character could also be found, e.g., in the Code of Hammurabi King of Babylon, the teachings of Sun Tzu, the practices of the Roman Empire”.

[7] These include the “principles of justice, honor (sic), and humanity” and “laws” or “law of humanity”. The four Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol II all reference laws or principles of humanity, as do several other treaties including the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty, and the Cluster Munitions Convention.

[8] Samera Esmeir, “On Making Dehumanization Possible”, PMLA, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 121, No. 5, 2006;

[9] Didier Fassin, Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present, Rachel Gomme (trans.), University of California Press, Berkeley, 2012.

See also:

- Stephanie Xu, Photographing neutrality: a personal reflection from the field, August 10, 2023

- Marina Sharpe, It’s all relative: the humanitarian principles in historical and legal perspective, March 16, 2023

- Pierrick Devidal, ‘Back to basics’ with a digital twist: humanitarian principles and dilemmas in the digital age, February 2, 2023

- Nils Melzer, Elizabeth Rushing, Humanitarian neutrality in contemporary armed conflict: a conversation with Nils Melzer, January 26, 2023

Comments