Warfare increasingly takes place in cyberspace. Consequently, the question arises how a digital analogy of the protective emblems, the red cross, red crescent and red crystal, could be realized. How could such an emblem be part of computer-to-computer communication? And how could its usage be limited to legitimate parties?

In this post, continuing the discussion on the viability of a ‘digital emblem’, Felix E. Linker and David Basin from ETH Zurich present an overview of ADEM – an ‘Authenticated Digital EMblem’ – and how it would operate in an armed conflict.

All militaries and most armed groups know how the red cross, crescent or crystal work in the real-world: you see a building, a person, or a vehicle, and if they have the emblem on them, you know they are entitled to protection under international humanitarian law (IHL). As the world is digitalizing, humanitarians are asking the question: is it possible to introduce a digital marking that could pass the same message to cyber operators?

Transferring the concept of the distinctive emblems into the digital world comes with unique challenges.

First, where should one put the emblem? One may want to mark a doctor’s laptop, but can it display the emblem if the computer is used for military communication as well as medical duties? The emblem could signal a hospital’s website, but what if the server hosting the website also runs a chat server that terrorists use to communicate? Computing is performed over many layers of services, and determining the layer on which the emblem should be placed is not always straightforward.

Second, with modern cyberattacks, humans tend to pull the strings of programmes doing the job for them rather than intervening themselves. Picturing cyberattacks as a linear process – a hacker pointing a cyber-rifle at a cyber-target and pulling the cyber-trigger – is flawed. It is more accurate to picture cyberattacks as intricate marble runs where launching an attack means having built the run and letting a marble go. Only after passing many junctions and tunnels does the marble eventually reach its destination, only the marble in this scenario can make decisions – it is a programme! Such a programme could be malware, or a forensic tool used by an investigator. A digital emblem should allow all such tools to identify protectively marked targets or communication. To put it differently: How can one teach programmes to check whether something is digitally marked as protected?

A third and final challenge is that everyone can claim they are protected. If showing a digital emblem were as easy as downloading and printing an image of a red cross, everyone would do it, and it would quickly become meaningless. Using cryptographic tools such as digital signatures does not solve this problem immediately; if someone wanted to, they could generate as many cryptographic keys and digital signatures as they pleased. How can we ensure that a digital emblem is only used by legitimate parties?

Stepping up to the challenge: ADEM

In 2020, the ICRC reached out to the Centre for Cyber Trust, a joint endeavor by ETH Zurich and Universität Bonn, to meet these challenges. As a response, the Centre proposed ‘An Authenticated Digital EMblem’, also known as ADEM. ADEM has three types of users: protected parties (PPs), who are eligible to claim protection for their digital infrastructure; authorities, who can attest that a PP is eligible to claim protection; and verifiers, who seek to distinguish protected from unprotected digital infrastructure. How does ADEM meet the three challenges identified earlier?

With ADEM, PPs can claim protection for their digital infrastructure as it appears to outsiders, meaning a specific type of communication over a specific network address. Software engineers love abstractions and, hence, the internet is full of them. Sometimes, when you seem to be communicating with one computer, in reality you’re in contact with a different computer behind the scenes, or what appears to you as one website is actually a network of servers to balance the load. In many cases, you cannot distinguish from the outside what happens behind the curtains. Therefore, ADEM allows one to claim protection for entities as they are recognized from the outside.

In ADEM, digital emblems are machine-readable and cryptographically secured claims of protection. This serves two purposes. First, recall that only programmes need to understand whether a digital entity is protected. Therefore, emblems are machine-readable. Second, cryptographically secured emblems account for the need to only have legitimate parties use the emblem. To be cryptographically secured means that every digital emblem comes with a digital signature, which serves the same purpose as the QR-code on your digital vaccination certificate. A programme can pull out its ‘QR-code reader’, scan the signature on the emblem, and check two things: that what has been signed was not altered by anyone else, and the identity of who signed the digital emblem.

However, the signer’s identity cannot be verified as part of the emblem; the emblem only comes with a very long number, a string of bits and bytes, a so-called public key. Public keys barely mean anything on their own. If you wanted, you could generate an endless number of keys and change them as you wish. So how can the programme associate the signer’s identity with that public key and who is behind the claim of protection?

This is not a new problem. Public key infrastructures (PKIs) were built to ascribe ownership to public keys. In fact, you were using a PKI when you connected to this website: the web PKI. In the web PKI, public keys are associated with domain names, e.g., blogs.icrc.org in this case, so that you can establish confidential connections to websites using HTTPS. The web PKI uses certificates to establish these associations. ADEM uses a similar approach, but here certificates are called endorsements.

To understand how endorsements work in ADEM, let us first take a step back. Digital emblems are claims of protection under IHL. These claims matter most in times of conflict. And in times of conflict, those who are interested in verifying the legitimacy of claims of protections are likely the parties to the conflict. At the same time, the conflicting parties are those who can attest a PP’s right to claim protection under IHL.

This setting opens the door for an interesting design decision: Usually, PKIs come with authorities that are given the power to freely make claims about public keys. For example, in the web PKI, your browser comes with a list of root authorities who can sign a certificate for any website they want. These central authorities are trusted, for the most part. In ADEM, there are no such central authorities. This lets ADEM fit the space of international diplomacy excellently, where it is hard to come to shared agreements. With ADEM, PPs can approach authorities individually, e.g., the conflicting parties, to ask them for endorsements. A PP can then distribute all of its endorsements in parallel.

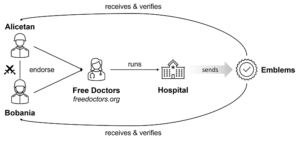

Imagine that two countries, Alicetan and Bobania, are fighting each other. An imaginary PP, the Free Doctors, can use ADEM to reach out to both countries separately. When the Free Doctors distribute claims of protection, they accompany them by endorsements both from Alicetan and Bobania. Whenever Alicetan seeks to verify a digital entity’s protected status, it will only pay attention to its own endorsement. The same applies to Bobania. Neither country trusts the other.

In real-world conflicts, trust relations would not be as simple. Likely, countries would not only trust their own endorsements, but also independent endorsements or endorsements from allies. ADEM’s key feature is that it does not dictate technically who can make a judgement on an organization’s status to be a protected party. This judgement is left to the courts.

Figure 1. ADEM’s trust model and verification loop. Alicetan and Bobania endorse the Free Doctors who run a hospital. The hospital distributes emblems that are again received and verified by Alicetan and Bobania.

* * * * *

As it stands, ADEM’s development is not completed but is an ongoing process, fed by consultations with its prospective users and experts in the domain. Researchers at the Centre for Cyber Trust ensure that ADEM will stand the test of reality and hope that it one day may serve to prevent accidental attacks on a hospital’s digital infrastructure and other entities protected under IHL in regions experiencing armed conflict.

See also

- Antonio De Simone, Brian Haberman, Erin Hahn, Identifying protected missions in the digital domain, September 23, 2021

- Tilman Rodenhäuser, Laurent Gisel, Larry Maybee, Hollie Johnston & Fabrice Lauper, Signaling legal protection in a digitalizing world: a new era for the distinctive emblems?, September 16, 2021

- Kubo Mačák & Ewan Lawson, Avoiding civilian harm during military cyber operations: six key takeaways, June 15, 2021

- Kubo Mačák, Tilman Rodenhäuser & Laurent Gisel, Cyber attacks against hospitals and the COVID-19 pandemic: How strong are international law protections? April 2, 2020

Comments