Fourth and final part of the article “You have mail: Letter from Lebanon, a film by John Ash”, an analysis of this short film produced in 1984 by the ICRC. Click here to read the first part, second part or third part.

An appeal sealed in an envelope

Before returning to the enclosed space of his office, we hear Amiguet’s voice over the last images of the displaced people being reunited with their families, reminding us that “everything we do rests on a single principle, the principle of humanity, of life rather than death, of peace rather than war, of happiness rather than so much suffering” [00:28:13–00:28:25], a subtle and beautiful allusion to the words of the female narrator earlier in the film: “But humanitarian work is concerned with life, not death; hope, not grief”, which were voiced over the images of the corpse being taken to the morgue. We have come on quite a journey in twenty minutes of film.

Then, pen in hand, the delegate from Switzerland reflects on the primary purpose of humanitarian action as understood by the ICRC [00:28:27–00:28:49]:

“Who are we, coming from a small and peaceful country, to say where the happiness of others lies? Who can ever say? But suffering, that can be seen for itself. A mutilated child? That demands action, not words. A father in prison? It’s not justice that concerns us, but his everyday needs.”[1]

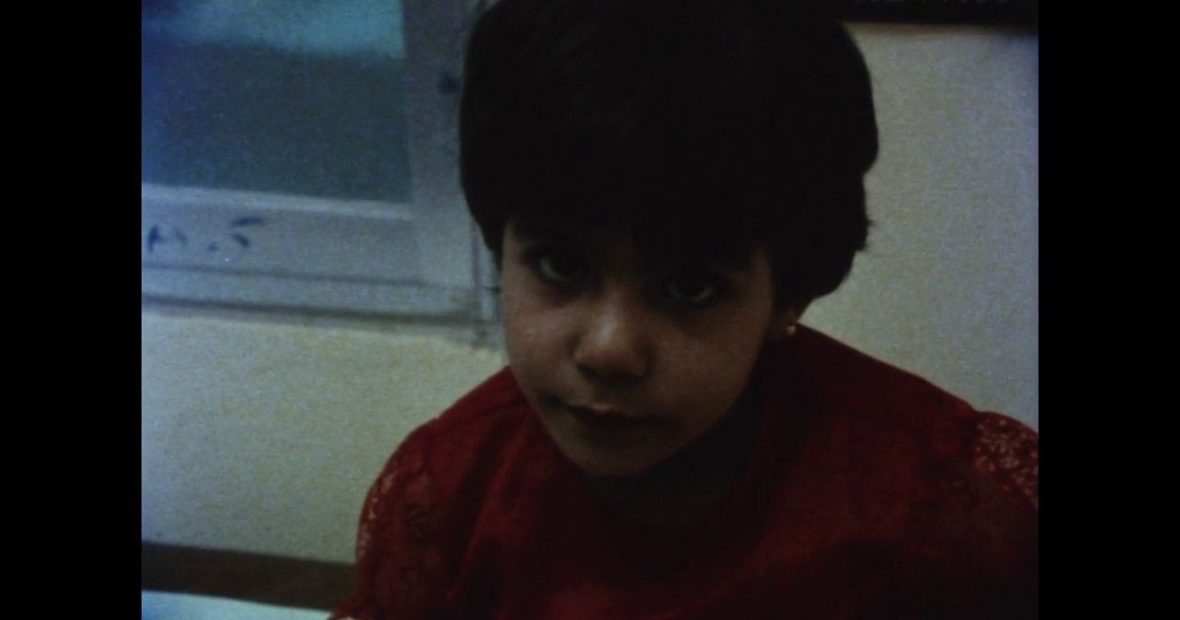

Ash immediately shows this “suffering that can be seen for itself” with images of a little girl and a young boy who have lost legs and a man who has lost his forearm, all of whom are being cared for in an ICRC orthopaedic centre, where they are fitted with prostheses. But simply showing suffering on film is still not enough to prompt what is ultimately essential [00:28:54]:

“If action is to work, it depends on something all too rare today: the will to act, to really do something for those in need. Without that will, from governments to the volunteers in the field, international humanitarian law will remain just words in a book, sheets of paper.”

In this short film, the public and private dimensions of language – the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Amiguet’s letter – are combined with the language of film in a forceful argument that seeks to stir the viewer’s conscience. But, without the will to act, the written word is a dead letter; and the same can be said for the medium of film, despite the emotional impact of the images. The final critical factor is the Other’s will to act, something on which a film can only have a transient and limited impact.

It is precisely in order to maximize this impact that Ash chose to wrap his cinematographic intention up in the story of a hand-written letter. This allowed him to intensify the film’s message by involving each spectator as it were personally; because the hand-written nature of a letter, compared to other types of texts, creates a personal link between two individuals. On this personal touch rests the hope that the letter will not become simply more “sheets of paper”.

So, in its closing images, the film focuses on the routine sequence of actions that ensure the letter is sealed and safely sent off to the recipient. When he has finished writing his letter and put it in an envelope, Amiguet calls his secretary in so that she can send it off with all the other letters. She puts it in a large envelope labelled “PRIVATE MAIL” in three languages – the same in which the film was produced – while he returns to his work. The delegate has said what he had to say.

Letter from Lebanon (© ICRC / ASH, John / 1984 / V-F-CR-H-00165): [00:29:43–00:30:56]

It is now for us, the viewers, to get involved. We have “read” the letter, we have seen its contents and we have been moved by the plight of the people who appear in it. We have also learnt that this letter is addressed to each of us personally. Of course, this does not mean it is posted to us as individuals with our first and last names; but on a deeper, more visceral level, it is addressed to each of us as human beings.

All that remains is for us to have the courage to open the envelope, a gesture that would indicate that we accept the humanitarian commitment the letter is asking us to make. To bring this call to action as close to us as possible, Ash places the sequence showing the first stage of the letter’s journey at the very end of the film, while the final bars of the Scheherazade theme are playing and the closing credits roll. The close-up of the envelope will also be the very last image we see. Structurally, Ash could not have brought the Letter from Lebanon any closer to the audience.

And then what?

As with the documentation about how the film was shot and produced, we have little information about how Letter from Lebanon was broadcast or how it was received. We do know that it was shown to the ICRC team in Beirut and to representatives of the Lebanese Red Cross, and that not everybody liked it. It was produced in French, English and Arabic, and intended for wide distribution and an international audience. It was shown on French-language Swiss television in 1984[2]

According to the 1984 Annual Report, the Division of Audio-Visual Communication had been extremely busy that year: “No less than 16 films were either produced or adapted by the DICA in 1984, some of these being for National Red Cross Societies. About 300 16 mm copies and 350 video copies were made of these films.”[3] Letter from Lebanon is not mentioned, as space was limited in the report. But, not without reason, a few lines were devoted to a film by Peter Amman, Plea for Humanity, which had been awarded a “‘prize for quality’ by the Swiss Federal Department of the Interior.[4]

The least that can be said is that, on a tight budget and without disappointing the DICA’s expectations, John Ash had succeeded in making a high-quality film that still has the power to touch us deeply today.

[1] Our emphasis.

[2] Letter from Lebanon, from the Radio télévision suisse (RTS) archives, available in French at: https://www.rts.ch/archives/tv/divers/archives/8096130-lettre-du-liban.html, accessed 8 December 2019. The same content is also available at: https://notrehistoire.ch/entries/L28LRmqMYKA, accessed 8 December 2019.

Comments