Context, types and limitations of these operations

Introduction

The Spanish Civil War, which lasted nearly three years, played a decisive role in shaping how the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) would have to adapt its humanitarian work to new constraints. Because the conflict was a civil war, the ICRC was extremely limited in what it could do, from both a legal and an operational perspective.[1] Evacuating civilians – and even more so children – was therefore a delicate balancing act. For almost the entire war, there were two National Societies, one Republican Red Cross and one Nationalist Red Cross, and the ICRC had to maintain a dialogue with both of them, particularly as the front lines shifted in the north.

From the outset, the evacuations were never just a domestic affair; there was always an international component. France, England, Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, Mexico and the USSR were among the states to host evacuated children. However, the ICRC was not systematically or directly involved in the evacuations to Mexico or the USSR. The relationship between these countries and Spain being what it was, the children evacuated there were unlikely to be repatriated quickly. The ICRC therefore focused on activities to keep the families in touch, and served as an intermediary in a secondary role only, and not for the evacuations themselves. In all, more than 34,000 children were evacuated, and only some 20,000 were repatriated.[2]

Given the constant state of tension throughout this period, the ICRC had to adapt its humanitarian response continually to balance the two factors making up the children’s best interest: their need to be with their families and the duty to protect them from the dangers on the front lines and in the rearguard. That is why, in the first few weeks of the uprising – before it became clear that the conflict would be lengthy – the priority was reuniting the children with their families quickly. But beginning in 1937, when it became clearer that the war would drag on, sheltering the children from the air raids became the priority. The ICRC had not intended for the children to be away from their families for so long; rather it was the result of the ideologies and strategies underlying the conduct of hostilities.

The evacuations of children were of three different types, almost all of which took place between September 1936 and September 1937. First were the evacuations to reunite children with their parents, when the children found themselves in one of the conflict zones. These evacuations followed a semicircular path, with repatriations occurring a relatively short time thereafter. Second were the evacuations to remove children from the path of the fighting or occupation, which were necessarily for a longer period. These first two types very often involved another country as a transit country or as a host country for a medium- to long-term stay. Third were the evacuations to Mexico or the USSR, prompted by the advancing Nationalist troops and the radicalization of national and international ideologies. These evacuations revealed the ICRC’s limitations regarding repatriations. The three types of evacuation differed in their planned timing and intended goals, which depended on the course of the military operations and, to a certain extent, assumptions about the ideology of the forces present. These are of course invented categories, but they lend a certain structure to the discussion.

Evacuation of holiday-makers

The pronunciamiento that triggered the uprising came as a surprise and was a relative failure, resulting in a country divided between those provinces that rose up and those that did not. Given that it happened in the middle of the summer, on 18 July 1936, many children were away at summer school camps[3] or visiting family members and got caught in regions under the control of one side or the other.[4] The ICRC and the International Save the Children Union (UISE)[5] responded quickly, evacuating and quickly repatriating children. The ICRC assisted children at around 30 summer camps, particularly at 11[6] located in territory controlled by the side opposing the one controlling the area where the children’s families were. At first the ICRC’s information about the camps was piecemeal, particularly about those groups that had come from the Nationalist zone (e.g. Burgos or Grenada) and were in Republican territory. More was known about the camps of children from the Republican zone (mainly Madrid and Toledo), thanks to the map provided by the UISE to ICRC delegates in Madrid.[7] The members of the ICRC’s Spain Commission[8] often spoke of the key role played by the UISE in helping and protecting children, and did not hesitate to invite Frédérique Small to speak about it in March 1937.[9]

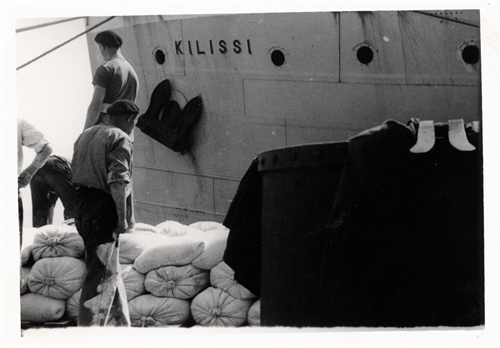

As early as August 1936, the French government was asking the ICRC, through the ICRC’s delegate-general to Spain, Dr Marcel Junod, to confirm the arrival of the cargo aboard the steamship Kilissi, which was transporting food and medical supplies to the port of Santander.[10] Dr Junod arrived on 10 September on board the French warship Alcyon and decided, 48 hours later, to seize the opportunity to evacuate some 300 children and their school teachers who were stranded in the region.[11] They sailed on the Kilissi to Saint-Nazaire, where they arrived on 13 September, before being lodged in barracks in Ancenis, which was already hosting more than 200 children.[12] They were repatriated to Spain and back to their families a few days later, some to Madrid and others to Toledo.[13]

Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939, Santander. The steamship Kilissi and its cargo. V-P-HIST-02222-10A, ICRC archives (ARR)

Three weeks later, the UISE facilitated the evacuation of 474 children[14] from Santander on board the Norwegian cargo ship Ala. The children had been at summer camps in the Nationalist zone. Daniel Clouzot, an ICRC delegate, reportedly boarded the aviso Arras on 7 October at the invitation of the French embassy and got off at Laredo, on the Cantabrian coast, in the hopes of meeting the Ala.[15] However, the Ala was not there when he arrived and, concerned – especially because the Ala was not equipped with wireless telegraphy – Clouzot inquired with the provincial government. The Ala apparently arrived in Santander the next day and, thanks to the instructions Clouzot had left with the French attaché he had been with on the Arras, the children were taken to the port of Verdon, in the French department of Gironde, where some received medical treatment. They were repatriated to Barcelona four days later, on 13 October, entering Spain from France at Cerbère, a major crossing point to Catalonia in the early weeks of the war. This was just one example of the efficiency of these swift evacuations.[16]

Spanish Civil War 1936–1939, Santander, October 1936. The aviso Arras, which took Daniel Clouzot to meet the Ala. V-P-HIST-02224-14, ICRC archives (ARR)

At almost the same time, Dr Junod was repatriating a group of around 40 girls on a summer school trip to Logroño, which was about 150 kilometres south of Guecho (Getxo in Basque), near Bilbao, where the children were from. The operation got off to a bad start, however, because the local branch of the Nationalist Red Cross had sent a letter,[17] delivered by Dr Junod to the Basque authorities, stating that the girls refused to be repatriated and signed by eight of them. In the end, discussions did lead to their return, under the auspices of the ICRC and the consul of Cuba.[18] What distinguished this operation was that it was part of an asynchronous exchange of prisoners, a practice that became increasingly common as the war went on. Dr Junod recalled in his memoires a heated discussion he reportedly had with the Count de Vallellano, the president of the Nationalist Red Cross, in which Dr Junod says he questioned the honour and the word of the insurgents, who were refusing to free a number of Basque hostages equivalent to 130 women from the aristocracy on the opposing side.[19] Daniel Clouzot confirms Dr Junod’s memoires in his report about 41 children being returned to Las Arenas port on board the British torpedo boat Esk on 16 October, six days after women detained at Los Ángeles Custodios convent were freed.[20] That repatriation was no doubt the first from the Nationalist zone.[21]

Spanish Civil War 1936–1939, Bilbao, 1936. Arrival of the Guecho camp-goers before the Basque soldiers. V-P-HIST-02224-11A, ICRC archives

In early November, children from Bilbao at a camp in Laguardia, in Álava Province in the Basque Country,[22] were carried to the international zone of Las Arenas port by a British ship, most likely HMS Exmouth. The operation was reported in La Voz newspaper of 6 November 1936, stating that there were 30 boys and 72 girls from the parish of Saint Vincent of Bilbao on board.[23] The article said the children boarded the Exmouth in San Sebastian and arrived in Las Arenas five hours later, accompanied by a “Dr Junaud, president of the International Red Cross”, presumably Dr Marcel Junod.

Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. San Sebastian, November 1936. Children being evacuated from the Laguardia summer camp waiting to board the British naval ship. V-P-HIST-01860-09, ICRC

Through these operations, no less than 1,326 children stranded at summer camps during the armed uprising received the ICRC’s help to return to their families.[24] A small number of the children could not be repatriated until 1937, as will be explained below.[25] The ICRC compensated in part by offering its tracing services to help the children and their families stay in contact.[26] These services quickly became a necessity as a growing number of people disappeared in Madrid in the weeks following the fighting in November 1936. The ICRC’s Spain Commission first stationed staff members in Madrid and Barcelona, and then also in Burgos and San Sebastian, to handle requests from worried family members seeking news from loved ones.

Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. Madrid, 1936. People waiting in line outside the ICRC’s delegation for news of loved ones. V-P-HIST-01850-15, ICRC archives

As the war went on, evacuating children, which had always been administratively and logistically complex, only grew more complicated, and November 1936 marked a turning point. The “column” war over and the atmosphere was tense in the lead-up to the battle in the capital – both of which were likely major factors in the difficulties faced by humanitarian organizations in Spain.

Evacuations from the path of the fighting or occupation

The first half of 1937 saw an increase in aerial bombings, especially in the north.[27] The successive evacuations of children from the Basque Country and from Santander and Asturias were not as well-documented as those from Madrid to Catalonia and Valencia, but they were no less significant. Negotiations to evacuate the remaining summer camps stalled, becoming a source of concern for the ICRC, which was contending at once with the movements of people within Spain and exiting the country.

The first displacements within Spain were the result of the troop advances on General Franco’s orders,[28] which in October 1936 clearly seemed to be headed for Madrid. Evacuations to Valencia, Catalonia[29] and the Basque Country appeared imminent. However, by the time the first clashes happened in November, Madrid’s population had swollen by half, as civilians in the surrounding regions sought temporary refuge there.[30]

Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. Madrid, 1936. In the capital, the fear of air raids was constant. V-P-HIST-01847-18, ICRC

Related to the evacuation of children, it is also worth mentioning the delicate and partially unexplained matter involving the delegate Georges Henny in late 1936.[31] On 8 December, Henny was exceptionally permitted to travel on board a French embassy plane that made weekly trips between Madrid and Toulouse. Henny took advantage of the trip to repatriate two girls, ostensibly the daughters of Dr Cabello, a close friend of the president of the Spanish Republic, Manuel Azaña (Cabello lent Azaña his Montauban apartment after he left Spain). During the flight, a military fighter fired on the plane, seriously injuring the ICRC delegate and hitting Louis Delaprée, a correspondent for France-Soir newspaper, in the thigh and gut, killing him. The airplane managed to land, and Andrés de Vizcaya, the health representative for the Republican Red Cross and a deputy delegate at the ICRC’s office in Madrid, had the girls taken to hospital and eventually repatriated to France. Georges Henny spent a few days recovering and then left Spain and did not return for the rest of the conflict.[32]

Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. Madrid, December 1936. Andrés de Vizcaya (on the right) at the hospital bedside of the delegate Georges Henny. V-P-HIST-01861-17A, ICRC archives

In late spring 1937, Andrés de Vizcaya was responsible for setting up negotiations with the Republican authorities for a large-scale evacuation from the capital. The ICRC’s delegation in Madrid went to Valencia to negotiate with the foreign affairs and justice ministries, which seemed more receptive to the ICRC’s grievances after the Largo Caballero government was ousted [33] and Juan Negrín became prime minister.[34] On 15 June, Vizcaya reported having received assurances from the secretary of Manuel de Irujo, the minister of justice, that he was favourable to a large-scale evacuation.[35] The evacuation took place a few weeks later and was one of the few evacuations of the sort the ICRC managed to negotiate. It allowed many children to remain with their parents, at least for a while longer. By this point, the problem of Madrid was being compounded by the evacuations on the northern front, no less crucial.

Between March and July 1937, Franco’s troops focused their efforts on the north. The subsequent battles allowed the British navy to play a significant role in the evacuation of children in the region. To Franco’s dismay, many British destroyers were sailing just outside the three nautical miles of Spain’s territorial waters. The Nationalists were forced to restrain themselves in the face of what they considered affronts by the Royal Navy and British merchant marine in that part of the Bay of Biscay and the Cantabrian sea, since the United Kingdom did not recognize them as combatants.[36]

Evacuations to other countries without any plans for repatriation were undertaken at the initiative of the Republican government and the Basque Country government. The Republican government saw it as an alternative to moving children around Spanish territory and the Basque government quickly chose to send them to France, the UK and Belgium. Marques saw in this difference of treatment not humanitarian concerns but the ideological desire of the Basque government to place “its” children outside the Nationalists’ sphere of influence and thus permit their identity to live on, even in exile.[37]

Alted Vigil stated that the evacuation of children from the north quickly became a propaganda tool, with the Nationalists and the Basque and Republican authorities insisting that the bombing had been indiscriminate, particularly the Italian bombing of Durango and the German bombing of Guernica.[38] However, while the Falange berated the evacuations to the USSR, the Nationalists did not criticize those to other countries in Western Europe.[39] Likewise, the Basque clergy, who were bitterly divided on whether to lend support to the independent government, which was allied with the Republican forces,[40] expressed serious reserves about evacuations of children to other countries. Once Bilbao fell, repatriation became the central issue. The Nationalists expressed this politically by forming a children’s protection council in May 1937. The Republicans issued a decree in October 1937 granting custody of evacuated children to the consular authorities in the countries they had been evacuated to, in order to prevent the children from being repatriated.[41]

Philippe Hahn, an ICRC delegate stationed in Barcelona, reported a problem that had been growing over the course of 1937. Evacuations without some sort of compensation had been getting increasingly difficult, and both sides were insisting on exchanges instead. The idea of exchanging military or civilian prisoners for children had been a divisive issue for months, including between the Republican Red Cross and the ICRC. The ICRC delegate Georges Henny was in favour of getting the women held in Bilbao prisons released in exchange for the evacuation of the children from the La Granja summer camp. Andrés de Vizcaya, Dr Junod’s deputy, was against it.[42] This is just one example, and these issues were compounded by the even thornier issue of assessing the level of risk in a given area. The issue was not new, but it became increasingly sensitive. The Spain Commission itself considered in October 1936 whether or not to repatriate the children at La Granja camp to Madrid, depending on whether the request came from the parents or the authorities.[43] Around the same time, Daniel Clouzot and Dr Junod met with the president of the Basque Country autonomous community to discuss the evacuation of the Guecho summer camp (outlined above). Daniel Clouzot emphasized the difficulty of repatriating children to Bilbao, as the city was considered particularly likely to be bombed, while also confirming that the parents’ wishes were most important.[44] Georges Graz, a delegate stationed in Bilbao, took an even more radical position: he objected to any evacuation of unaccompanied children from the north and insisted on requiring the children to be reunited with their parents if the parents requested it.[45]

Philippe Hahn met with the minister of justice, Manuel de Irujo, to follow up on Andrés de Vizcaya’s visit, and this meeting seems to have produced results, getting a hundred or so children evacuated towards Puigcerda.[46] That is why Clouzot, who arrived in Latour-de-Carol from Geneva on 28 September, insisted that the prefect of the Pyrénées-Orientales department allow the children to cross the border that day, and not the following day as had initially been planned. At the same time, Hahn was handling the negotiations within Spain to reach an agreement on the children’s eventual return. The atmosphere surrounding this type of evacuation was extremely tense at the time, what with the Asturias Offensive, by which the Nationalists intended to seize all of northern Spain not yet under their control. It was therefore deemed preferable for two of the children, whose parents were from Asturias, to remain in Republican territory, apparently to protect them from reprisals and the ongoing fighting. Another girl, who had a valid passport and money, also left the group to head to Nantes, where family members awaited her. The delegates Hahn and Clouzot escorted the 97 other children to Hendaye via Toulouse, making use of the diplomatic, financial, administrative and resupply skills they had built up over the past few months.[47]

Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. Puigcerda, on the French–Spanish border, September 1937. Evacuation of children to France. V-P-HIST-01854-11, ICRC archives

The two Red Cross organizations for Spain served alongside the ICRC’s delegations as intermediaries in family reunions, dealing with the administrative hassles imposed by each of the sides. Despite the difficulties, family reunions continued at a reasonable pace until November 1937, when they stopped.[48] The north had, it seemed, been definitively taken by the Nationalists, who henceforth controlled more than half the peninsula. The Republican institutions left Valencia for Barcelona.

To a lesser extent than France, other Western European countries also hosted Spanish children in spring 1937. An estimated 4,000 children went to England,[49] To a lesser extent than France, other Western European countries also hosted Spanish children in spring 1937. An estimated 4,000 children went to England, half of whom were repatriated a year later, in May 1938. A similar number went to Belgium, but the evacuations were more spread out, starting in 1936 and continuing until early 1939. After France, Belgium likely took in the most Basque children. Switzerland also hosted a few dozen children after the Nationalists seized Bilbao. The children had received medical treatment before leaving, it seems at the request of the Francoist authorities. The number of children arriving in Switzerland from Spain was at its highest in the last few weeks of the civil war, in January and February 1939. Denmark hosted some 250 children as well, between November 1937 and November 1938, before sending them on to France. Only a very small number of children who were evacuated to these four countries stayed on permanently. It is also unclear what part the ICRC played in organizing these evacuations. It seems that they were mostly organized through union organizations or, very occasionally, Catholic associations, and left-wing political parties or associated bodies, such as the Belgian labour party or the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief. Given the polarizing political ties of most evacuations in spring 1937, the ICRC would not have been involved.[50]

Evacuations to Mexico and the USSR

There was a complex web of reasons behind the choice to evacuate children to Mexico and the USSR and have some of them settle permanently. However, for the purposes of this paper, we will merely state that these actions, as with Italy’s and German’s involvement on the Nationalist side, were a sign that the conflict was taking on an international dimension.

It was clear as soon as the war ended that these two states would be the only ones staunchly opposed to returning the exiled children[51] and reuniting them with their parents, because of the support that the Cárdenas and Stalin regimes had lent to those on the Republican side. What happened to these children remains murky, given the difficulty of finding out where they were living and whether any attempt was made to repatriate them. It would therefore be worth examining. The ICRC’s archives show that it was also difficult to get detailed information about these evacuations, given that Mexico and the USSR did not recognize[52] General Franco’s government.

In Franco’s emerging state, the children’s protection council was replaced on 1 July 1938 by the Extraordinary Delegation for the Repatriation of Minors (DERM),[53] which worked until 1954 to repatriate children.[54] The DERM made use of documents seized at the social welfare office on hundreds of children evacuated from Bilbao – many of them to the USSR – after Santander fell to Franco’s forces in August 1937. It also gave them an idea of the scale of their task.[55] It seems that the host countries were reluctant to return the children to Spain just because the DERM requested it, and that the children’s parents, whether exiled or not, had expressed concerns about what would happen to the children. However, once the civil war was over, and even more so once the Second World War began, the returns gathered pace. While only a few hundred children returned in late 1937, several thousand returned in 1938 and 1939 – likely more than half those who had been evacuated.[56]

Mexico, led by General Cárdenas, was an important ally of the Republican government in Spain. President Cárdenas was so taken with the idea that he soon formed a section for children, led by his wife, which organized a high-profile evacuation of the “Morelia kids”.

The children were both boys and girls and most were between the ages of four and 12.[57] Although we do know where they were from originally, it is hard to know where they had travelled before the evacuation. It seems at least that most had been evacuated from Guipúzcoa to France and then back to Catalonia or Valencia.[58] How they got from Catalonia and Valencia back to France, where they started their transatlantic journey, is unconfirmed. In any case, they boarded the French ship Mexico in Bordeaux, France, on 25 May 1937 and landed in Veracruz, Mexico, on 7 June, and were lodged in a boarding school in Morelia, in the state of Michoacán.[59]

Ayuda! Newsletter of the committee to aid the children of the Spanish people, No. 3, September 1937.

The technical committee of Franco’s government heard about the evacuation from its representative to the United States, the unofficial diplomat J.F. Cárdenas. It asked the president of the Nationalist Red Cross, the Count de Vallellano, to request that the ICRC inquire with the Mexican Red Cross and the Mexico government about the conditions in which the children were being kept.[60] The president of the Mexican Red Cross responded on 18 August that the conditions were satisfactory given the number of children and the cultural differences between the two countries.[61] Once the representative of Franco’s government in the United States had the list of the evacuated children, the ICRC offered its services to repatriate the children, provided the children’s parents had requested it. Thus, thanks to the individual files created by the ICRC, more than half the children were matched with their parents’ current address, with the aim of repatriating them before the end of the war.[62] All the work resulted, however, in a relatively low rate of repatriation during the presidency of General Cárdenas and his successor.[63]

It is worth noting how disproportionately few children were evacuated to Mexico during the conflict compared to the many adults who sought refuge there between 1939 and 1942. Mexico hosted many high-profile political, military and intellectual figures, but only 456 children, which seems to indicate that the evacuation had been judged by the many controversies it generated. The situation was completely different with the USSR, where the vast majority of Spanish exiles were children evacuated there in 1937 and 1938.[64]

The ICRC estimated that around 2,000 children went to the USSR, in four journeys by sea.[65] Although most authors confirm that these four official journeys did take place, some believe the number of children was closer to 3,000 for the period between March 1937 and November 1938, and that there had been previous journeys.[66]

Much of the confusion, mix-ups and drama regarding the children’s origin occurred in beleaguered northern Spain. Most of the children on each of these journeys had been evacuated from cities where battles were taking place or about to take place, i.e. Madrid, Bilbao, Asturias, Santander and, in the weeks leading up to the attack on Barcelona, cities in Catalonia and Aragon and on the eastern coast. In addition, two of the boats stopped over in France, in large part to drop off children whose final destination was not the USSR. The other two boats headed for ports on the Baltic coast (e.g. Leningrad) and North Sea (Yalta).[67]

We know, as was said in the preamble, that the ICRC was not directly involved in the evacuations to the USSR, nor is there evidence that the ICRC endorsed them. However, for the two journeys with stopovers in France, we cannot rule out some ICRC delegates hearing about Soviet ships, such as the Kooperasiia and the Dzerzhinsky, or French-flagged boats, such as the Sontay, awaiting boats from Spain to take some of their passengers to Leningrad.[68]

Even before the end of the civil war, the future of the children evacuated to the USSR became a major political issue for the Burgos-based government, which made many ill-fated attempts at negotiations. The DERM called on Italy, then Germany and the Vatican to intercede with the Soviet authorities before the German–Soviet nonaggression pact was terminated, closing down these diplomatic channels for good.[69] Under these conditions, the ICRC’s role was minimal.

As they did for Mexico, the ICRC’s archives attested to the difficulties that the organization faced in obtaining information about the children evacuated to the USSR. Diplomatic recognition was a problem, as was the Soviet Red Cross’s inability to get authorizations from its government. Officially only group repatriations could be considered. There was also the issue of the costs of such operations. According to the delegation in Burgos in May 1939, the ICRC was not able to expedite parents’ requests for repatriation by sending them to the Soviet Red Cross.[70] In reality, the end of the conflict in Spain meant, as the delegate Jean d’Amman said in April 1939, that the ICRC could no longer carry out repatriations and had to limit itself henceforth to helping the families communicate.[71] The ICRC emphasized that repatriating refugees and the associated negotiations could no longer be at the organization’s initiative, unless there were particular circumstances that made it the only entity able to facilitate the return.[72] This position was pivotal in cases where the parents did not know where their children were, and meant that the ICRC had decided that, from August 1939, repatriations of Spanish children would in principle be the task of the consular officials and the Red Cross organizations for the relevant countries in Western Europe. The wording left open the possibility of participating, if necessary, in repatriations from Mexico and the USSR.[73]

In a note dated July 1939, the ICRC learned that there was a plan to exchange 2,000 child refugees in the USSR for 120 Russian sailors held in Palma.[74] The following month, Jean d’Amman[75] confirmed the plan and that it had failed, given that the sailors were released a different way.[76] 2,000 is roughly the total number of children that the ICRC thinks were evacuated to the USSR. Had the exchange been carried out, it would no doubt have been one of the organization’s greatest successes in Spain. Even though the operation was stopped before it even got going, it nonetheless shows the limits that the ICRC had to work within.

Conclusion

Judging by the evidence, the ICRC’s involvement in the evacuation of children seems to have been very welcome between September 1936 and September 1937, and then became gradually more discrete, both practically and operationally, as the conflict took on a more international dimension. The organization no doubt showed its efficacy in evacuating and repatriating the children in summer camps, and in evacuating civilians from Madrid to the east, but thereafter its involvement is harder to gauge. The ICRC’s delegations did not suddenly close their doors in autumn 1937, any more than its delegates stopped learning what was going on in Spain. But the arrival of other, more partisan humanitarian organizations[77] seems to have complicated its work. The ICRC was not at all or barely associated with most of the evacuations that necessarily involved a medium- to long-term separation and was notable by its absence in the evacuations of children to Mexico and the USSR. However, the ongoing presence in 1937 and 1938 of many of the ships that had transported children in 1936 suggests that the ICRC’s dense network of delegations in Spain was still working hard. Evidence of this is in the tracing service, set up by the Spain Commission. Around five million family messages transited through its central office in Geneva, and the last ICRC delegation in Spain, in Barcelona, remained open until September 1939. No doubt the information provided here will raise more, as yet unanswered, questions: What happened to the children in the various host countries? What information was the ICRC able to provide the families whose children were evacuated elsewhere in Europe? After the Second World War, was the ICRC able to repatriate children who remained in other countries? These are just some of the many subjects that have yet to be investigated in the ICRC’s archives.

Bibliography

Books and articles

Alonso, Charo, and Farré, Sébastien, El Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja y la repatriación de los refugiados españoles tras la Retirada [The International Committee of the Red Cross and the repatriation of Spanish refugees after the Retirada], in Anne Dubet and Stéphanie Urdician (eds), Exils, passages et transitions: Chemins d’une recherche sur les marges: Hommage à Rose Duroux, Presses Universitaires Blaise-Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand, 2008.

Alted Vigil, Alicia, El exilio español en la Unión Soviética [The Spanish exile in the Soviet Union], Ayer, No. 47, 2002.

Alted Vigil, Alicia, Las consecuencias de la Guerra Civil española en los niños de la República: de la dispersión al exilio [The consequences of the Spanish Civil War on children of the Republic: From dispersion to exile], Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Series V, Contemporary History, 2014.

Alted Vigil, Alicia et al., Enfants de la guerre civile espagnole: vécus et représentations de la génération née entre 1925 et 1940 [Children of the Spanish Civil War: Experiences and depictions from the generation born between 1925 and 1940], collective work, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1999.

Botti, Alfonso, La iglesia vasca dividida: Cuestión religiosa y nacionalismo a la luz de la nueva documentación vaticana [The Basque Church divided: Religious issues and nationalism in light of new Vatican papers], Historia Contemporánea, No. 35, 2007.

Marques, Pierre, Les enfants espagnols réfugiés en France (1936–1939) [Spanish refugee children in France (1936–1939)], AutoEdition, Paris, 1993.

Marques, Pierre, Le CICR et la guerre civile d’Espagne (1936–1939) [The ICRC and the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)], in Exils et migrations ibériques au XXe siècle, Vol. 2, 1995.

Mateos, Abdón, Los Republicanos españoles en el México cardenista [The Spanish Republicans in Cardenist Mexico], Ayer, No. 47, 2002.

Moreno Martínez, Pedro Luis, “Tiempos de paz, tiempos de guerra: la Cruz Roja y las colonias escolares en España (1920–1937)” [Times of peace, times of war: The Red Cross and summer school camps in Spain (1920–1937)]. Áreas, Revista Internacional De Ciencias Sociales, 2012.

Sánchez Ródenas, Alfonso, Los ‘niños de Morelia’ y su tratamiento por la prensa mexicana durante el año 1937 [The “Morelia kids” and their treatment by the Mexican press in 1937], Anales de Documentación, Vol. 13, 2010.

Sierra Blas, Verónica, En el país del proletariado: Cultura escrita y exilio infantil en la URSS [In the country of the proletariat: Written culture and childhood exile in the USSR], Historia Social, No. 76, 2013.

Background information

Bennassar, Bartolomé, La guerre d’Espagne et ses lendemains [The Spanish Civil War and its aftereffects], Perrin, Paris, 2006.

Clemente, Josep Carles, El árbol de la vida, la Cruz Roja en la guerra civil española [The tree of life: The Red Cross and the Spanish Civil War], editorial ENE Publicidad, Madrid, 1993.

García López, Alfonso, Entre el odio y la venganza: el Comité internacional de la Cruz Roja en la Guerra Civil española [Between hate and vengeance: The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Spanish Civil War], Espacio Cultura Editores, La Coruña, 2016.

Marques, Pierre, La Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre d’Espagne (1936–1939): Les missionnaires de l’humanitaire [The Red Cross during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939): Humanitarian missionaries], L’Harmattan, Paris, 2000.

Rekalde Rodríguez, Itziar, Escuela, educación e infancia durante la Guerra Civil en Euskadi [School, education and childhood in the Basque Country during the civil war], University of Salamanca, 2000.

Sierra Blas, Verónica, Paroles orphelines, Les enfants et la guerre d’Espagne [Orphan words: Children and the Spanish Civil War], Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016.

Online resources

The Spanish National Library’s digital publication library: http://www.bne.es/es/Catalogos/HemerotecaDigital/

The ICRC’s audiovisual archives: https://avarchives.icrc.org/

Research tools (ICRC archives)

Section C ESCI, Spanish War, 1936–1940

Section B CR 212, Spanish Civil War, 1936–1950

Additional sources (not cited)

Bugnion, François, Le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge et la protection des victims de la guerre, 2nd ed., ICRC, Geneva, 2000, English trans. Patricia Colberg et al. (trans.), The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Protection of War Victims, 2nd ed., ICRC, 2003, .

Carballés, Jesús Javier Alonso, “La historiografía sobre ‘Los niños del exilio’: la historia olvidada” [The forgotten story of the exiled children: A literature survey], in Exils et migrations ibériques au XXe siècle, Vol. 3, 1997.

Fernández Soria, Juan Manuel, “La asistencia a la infancia en la guerra civil: Las colonias escolares” [Aid to children in the civil war: The school camps], in Historia de la educación: Revista interuniversitaria, No. 6, 1987.

Gonzalez, Damian, “La guerre d’Espagne (1936–1939) : déploiement et action du CICR en images” [The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939): Response and work of the ICRC in pictures], blog of the ICRC’s library and public archives, 2019.

Legarreta, Dorothy, The Guernica Generation: Basque Refugee Children of the Spanish Civil War, University of Nevada Press, 1984.

Pretus, Gabriel, Humanitarian Relief in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), Edwin Mellen Press, 2013.

[1] Only Resolution XIV of the Tenth International Conference of the Red Cross of 1921, which was non-binding, gave the ICRC a legal basis on which to intervene in domestic conflicts at the request of a National Society.

[2] According to the figures from Spain’s general government archives (in Spanish): https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/areas/archivos/mc/centros/cida/guias-de-lectura/guia-exilio-espanol-1939-archivos-estatales/ninos-guerra.html.

[3] Many of these camps were operated under the educational programmes of the education and labour ministries. Others were organized by workers’ unions, child assistance programmes or Catholic associations.

[4] For an overview of the situation, see Pierre Marques, Les enfants espagnols réfugiés en France (1936–1939) [Spanish refugee children in France (1936–1939)], AutoEdition, Paris, 1993, pp. 30–34.

[5] The role played by the UISE in the evacuation of the children is not covered in detail here. For an overview, particularly on the activities of Frédérique Small, we recommend Mathias Gardet’s talk at the symposium Warriors without Weapons: Humanitarian Action in the Spanish Civil War and the Republican Exile, held at the University of Geneva on 27 and 28 October 2016.

[6] Pedro Luis Moreno Martínez, Tiempos de paz, tiempos de guerra: la Cruz Roja y las colonias escolares en España (1920–1937) [Times of peace, times of war: The Red Cross and summer school camps in Spain (1920–1937)], Áreas: Revista Internacional De Ciencias Sociales, 2012, p. 152.

[7] Ibid. p. 153, which mentions circular No. 331 issued by the ICRC; International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 18, No. 214, October 1936, p. 856.

[8] This was the ICRC’s coordinating body for operations in France and Spain, which met 365 times before 15 February 1938.

[9] ICRC archives, B CR 212 meeting minutes, 29 September 1936; ICRC archives, B CR 212 meeting minutes, 17 March 1937.

[10] International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 18, No. 213, September 1936, p. 754; Pierre Marques, La Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre d’Espagne (1936–1939): les missionnaires de l’humanitaire [The Red Cross during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939): Humanitarian missionaries], L’Harmattan, Paris, 2000, p. 55.

[11] ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-60, undated, it also talks about the evacuation of 40 foreign and Spanish “refugees”.

[12] Pierre Marques, op. cit., 2000, p. 55.

[13] International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 18, No. 213, September 1936, p. 754.

[14] These children had come from various camps near Santander.

[15] ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-52, 23 October 1936.

[16] International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 18, No. 214, October 1936, pp. 856–857; Pedro Luis Moreno Martínez, op. cit., p. 153.

[17] This letter is also mentioned in Daniel Clouzot’s report, ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-52, 23 October 1936.

[18] Itziar Rekalde Rodríguez, Escuela, educación e infancia durante la Guerra Civil en Euskadi [School, education and childhood in the Basque Country during the civil war], University of Salamanca, 2000, p. 877.

[19] Josep Carles Clemente, El árbol de la vida, la Cruz Roja en la guerra civil española, 1936–1939 [The tree of life: The Red Cross and the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939], editorial ENE Publicidad, Madrid, 1993, pp. 115–117; Marcel Junod, Le troisième combatant, Payot, Paris, 1963, pp. 79–80, English trans. Edward Fitzgerald, Warrior without Weapons, Jonathan Cape Limited, London, 1951, reprinted by the ICRC, Geneva, 1982, pp. 107–109, which mentions that the repatriation of these children was promised by the Nationalist Red Cross.

[20] ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-52, 23 October 1936; for more on the evacuation of women from the Los Ángeles Custodios convent, see the blog of the ICRC’s library and public archives.

[21] Clemente said it was the first group of children repatriated from a camp during the war, which is unlikely, Clemente, op. cit., p. 117.

[22] However, of the three provinces that declared independence (Álava, Guipúzcoa and Biscay), only Biscay and a part of Guipúzcoa were still under the independent Basque government during the evacuations of March 1937.

[23] Alfonso García López mentions this article in Entre el odio y la venganza: el Comité internacional de la Cruz Roja en la Guerra Civil Española [Between hate and vengeance: The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Spanish Civil War], Espacio Cultura Editores, La Coruña, 2016, p. 199. The digitized newspaper is available in the Spanish National Library’s digital publication library: http://www.bne.es/es/Catalogos/HemerotecaDigital/.

[24] Alfonso García López, op. cit., p. 199.

[25] Alfonso García López, op. cit., p. 153, which mentions that the archives of the Spanish Red Cross have no information after July 1937 about the camps that had yet to be repatriated. We know, for example, that a camp of scouts in the Pyrenees valley of Ordesa had to wait until April 1937 to be repatriated. After a stay in Lourdes, they were repatriated following discussions between the French foreign ministry and two parties to the Spanish conflict.

[26] Clemente rightly underlined that the tracing service was not mentioned in the agreements signed in Burgos and Madrid between the ICRC and the parties to the conflict, op. cit., p. 109.

[27] The arrival of the Italian Air Force (in response to the International Brigades being dispatched) and the Condor Legion and Madrid’s fierce resistance led Franco to concentrate on the north, on Biscay, Santander and Asturias. The Italian forces grew to around 50,000 combatants.

[28] Franco was formally proclaimed head of state by the military junta on 1 October 1936.

[29] Catalonia supposedly signed an agreement with the ICRC on 8 December 1936 authorizing the evacuation of non combatants, see Alfonso García López, op. cit., p. 186.

[30] Pierre Marques, op. cit., 1993, p. 25.

[31] One of the fullest accounts is in the book by Alfonso García López, which we have used for the summary here, op. cit., pp. 99–122. García López based his account in part on the ICRC’s archives and the report written by Henny himself (ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-58).

[32] For information about the people and reasons behind the attack, particularly regarding Henny’s visits to prisons in Madrid in October 1936 and theories about the Paracuellos del Jarama massacres, see Alfonso García López, op. cit., pp. 99–125, whose work is largely based on Pierre Marques, op. cit., 2000, pp. 115 ff.

[33] The Largo Caballero government didn’t survive its internal civil war between anarchists, anti-Stalinists and communists in Barcelona in May 1937.

[34] Alfonso García López, op. cit., pp. 206–207.

[35] ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-70, 15 June 1937.

[36] Aside from the humanitarian reasons, the British ships were there to evacuate their citizens from Spain, resupply northern Spain and transport Basque ore to the UK. See Pierre Marques, op. cit., 1993, p. 53.

[37] Pierre Marques, Les colonies espagnoles d’enfants réfugiés: un regard singulier [The Spanish camps of refugee children: a unique perspective] in Alicia Alted Vigil et al., Enfants de la guerre civile espagnole: vécus et représentations de la génération née entre 1925 et 1940 [Children of the Spanish Civil War: Experiences and depictions from the generation born between 1925 and 1940], collective work, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1999, p. 79.

[38] Alicia Alted Vigil, Le retour en Espagne des enfants évacués pendant la guerre civile espagnole: la Délégation extraordinaire au rapatriement des mineurs (1938–1954) [The return to Spain of children evacuated during the Spanish Civil War: The Extraordinary Delegation for the Repatriation of Minors (1938–1954)], in Alicia Alted Vigil et al., op. cit., 1999, p. 48.

[39] On 19 February 1937, Manuel Hedilla, interim head of the Falange and José Antonio Primo de Rivera’s successor, wrote an article saying that the “Valencia government” intended to send children to the USSR. He even called on the League of Nations to prevent it, through a letter to its secretary-general, Joseph Avenol. This story is told in Alicia Alted Vigil in Alicia Alted Vigil et al., op. cit., 1999, pp. 48–49.

[40] For an overview of the complex positions taken by the Basque and the Spanish clergy, and their respective relationships with the political authorities, based in large part on documents from the Vatican archives, see Alfonso Botti, La iglesia vasca dividida: Cuestión religiosa y nacionalismo a la luz de la nueva documentación vaticana [The Basque Church divided: Religious issues and nationalism in light of new Vatican papers], Historia Contemporánea, No. 35, 2007, pp. 451–489.

[41] Alicia Alted Vigil in Alicia Alted Vigil et al., op. cit., 1999, pp. 50–51.

[42] Pierre Marques, op. cit., 2000, p. 53.

[43] ICRC archives, B CR 212 meeting minutes, 7 October 1936. Ms Ferrière did not want to grant a request from the government in Madrid, but Mr Chenevière disagreed. The meeting minutes show that Daniel Clouzot believed that the delegate Broccard was the one who refused to carry out the repatriation and not the authorities in Burgos.

[44] ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-52, 23 October 1936.

[45] Pierre Marques in Alicia Alted Vigil et al., op. cit., 1999, pp. 79–80.

[46] Pierre Marques, op. cit., 2000, pp. 242–243.

[47] ICRC archives, B CR 212 GEN-52, undated.

[48] Beginning on 1 November 1937, the Republican authorities no longer fulfilled requests to issue passports coming from the Nationalist Red Cross, even for children. The authorities for the insurgency, in Burgos, quickly reciprocated, see Alfonso García Lopez, op. cit., p. 189.

[49] Most children from the Basque provinces had already been repatriated in September 1937.

[50] This information was taken from excerpts of Pierre Marques, op. cit., 1993, pp. 207–221.

[51] We should point out that around a hundred children returned to Spain or were reunited with their parents in another country before the end of 1939, according to Verónica Sierra Blas, Paroles orphelines, Les enfants et la guerre d’Espagne [Orphan words: Children and the Spanish Civil War], Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016, p. 86.

[52] Spain did not have full diplomatic relations with Mexico until 1977 (two years after the death of General Franco), and approached the USSR through their respective embassies in France until 1969.

[53] Six months earlier, the first government under Franco had been formed in Burgos.

[54] Verónica Sierra Blas, op. cit., 2016, p. 78.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid. pp. 84–85.

[57] Some authors say that some children lowered their age to avoid being conscripted, see Pierre Marques, op. cit., 1993, p. 222.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ayuda!, Bulletin du Comité d’aide aux enfants du peuple espagnol [Newsletter of the committee to aid the children of the Spanish people], No. 3, September 1937.

[60] Alfonso García López, Alfonso, op. cit., p. 200.

[61] ICRC archives, C ESCI 251, 18 August 1937 – the response from the president of the Mexican Red Cross, which took the form of a 21-page report on the conditions in which the children were kept and lodged. For the perspective of the Mexican press on the children’s living conditions and how they were kept in 1937, see Alfonso Sánchez Ródenas, “Los ‘niños de Morelia’ y su tratamiento por la prensa mexicana durante el año 1937” [The “Morelia kids” and their treatment by the Mexican press in 1937], Anales de Documentación, Vol. 13, 2010, pp. 243–256.

[62] Alfonso García López, op. cit., p. 201, which mentions that there were 169 individual files and that most of the children were repatriated in March 1939.

[63] For more on this see Abdón Mateos, Los Republicanos españoles en el México cardenista [The Spanish Republicans in Cardenist Mexico], Ayer, No. 47, 2002, pp. 122–123 and Alicia Alted Vigil, Las consecuencias de la Guerra Civil española en los niños de la República: de la dispersión al exilio [The consequences of the Spanish Civil War on the children of the Republic: From dispersion to exile], Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Series V, Contemporary History, 2014, p. 219; Alted Vigil mentions 56 other repatriated children, based on the figures from the Extraordinary Delegation for the Repatriation of Minors for November 1949, Alicia Alted Vigil in Alicia Alted Vigil et al., op. cit., 1999, p. 58.

[64] Though she provides no explanation, this was pointed out by Alicia Alted Vigil, El exilio español en la Unión Soviética [The Spanish exile in the Soviet Union], Ayer, No. 47, 2002, pp. 130–131.

[65] According to Alfonso García López, op. cit., pp. 201–202.

[66] See in particular Verónica Sierra Blas, En el país del proletariado. Cultura escrita y exilio infantil en la URSS [In the country of the proletariat: Written culture and childhood exile in the USSR], Historia Social, No. 76, 2013, pp. 127 and 135; and Alicia Alted Vigil, op. cit., 2002, pp. 131 and 144.

[67] Alicia Alted Vigil, op. cit., 2002, p. 144.

[68] The names of the carrier vessels were provided by Pierre Marques, op. cit., 1993, p. 202; the original source is Enrique Zafra et al., Los niños españoles evacuados a la URSS (1937) [Spanish children evacuated to the USSR (1937)], Editiones de la Torre, 1989.

[69] Alicia Alted Vigil in Alicia Alted Vigil et al., op. cit., 1999, pp. 56–57; Pierre Marques, op. cit., 1993, p. 203.

[70] ICRC archives, C ESCI 252, 25 May 1939.

[71] ICRC archives, C ESCI 252, 21 April 1939.

[72] Charo Alonso and Sébastien Farré, El Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja y la repatriación de los refugiados españoles tras la Retirada [The International Committee of the Red Cross and the repatriation of the Spanish refugees after the Retirada], in Anne Dubet and Stéphanie Urdician (eds), Exils, passages et transitions: Chemins d’une recherche sur les marges: Hommage à Rose Duroux, Presses Universitaires Blaise-Pascal, Clermont Ferrand, 2008, p. 86.

[73] Ibid. pp. 92–93.

[74] ICRC archives, C ESCI 252, 14 July 1939.

[75] Jean d’Amman was an ICRC delegate in the cities of Burgos and San Sebastian, both in the Nationalist zone when he was there.

[76] ICRC archives, C ESCI 252, 12 August 1939.

[77] For a fairly complete overview of the massive evacuations which took place between 1938 and 1939, which is rare among general works about the Spanish Civil War, see Bartolomé Bennassar, La guerre d’Espagne et ses lendemains [The Spanish Civil War and its aftereffects], Perrin, Paris, 2006, pp. 391–398.

Fascinating. I knew Daniel Clouzot. I own nearly all of his personal effects. There is very little information on him. I would love to talk with the author.

Dear Rhet, thank you very much for your enthusiastic comment on this article. The author (myself) may be reached at: dgonzalezdominguez@icrc.org

my now deceased friend fernando fernandez was one of those children. he told me about his evacuation but i never knew the whole story until i just read ur xpansive article. i just finished jessica fellows “the mitford vanishing” which led me to ur article. thank you, thank you for this comprehensive article. it should b paer of history classes in high schools & colleges everywhere. m. miller, toms river, nj

J’aime la France qui a accueilli ma mère, enfant de la guerre, par le couple Rousseau, de Paris. Merci grand-mère Louisette Rousseau, je me souviendrai toujours de toi