Treaty provisions are carefully crafted before they are agreed to and adopted by States, but no matter how detailed the language, unexpected circumstances may arise. The context may change, technologies may evolve, or other unforeseen developments may take place. On the other hand, those drafting a treaty may intentionally leave terms vague in order to preserve flexibility in interpretation or to secure the agreement of States that otherwise might not sign up to it. Given these and other challenges, how does one know how a given treaty should be interpreted and applied? One tool that is designed to assist scholars and practitioners is a commentary.

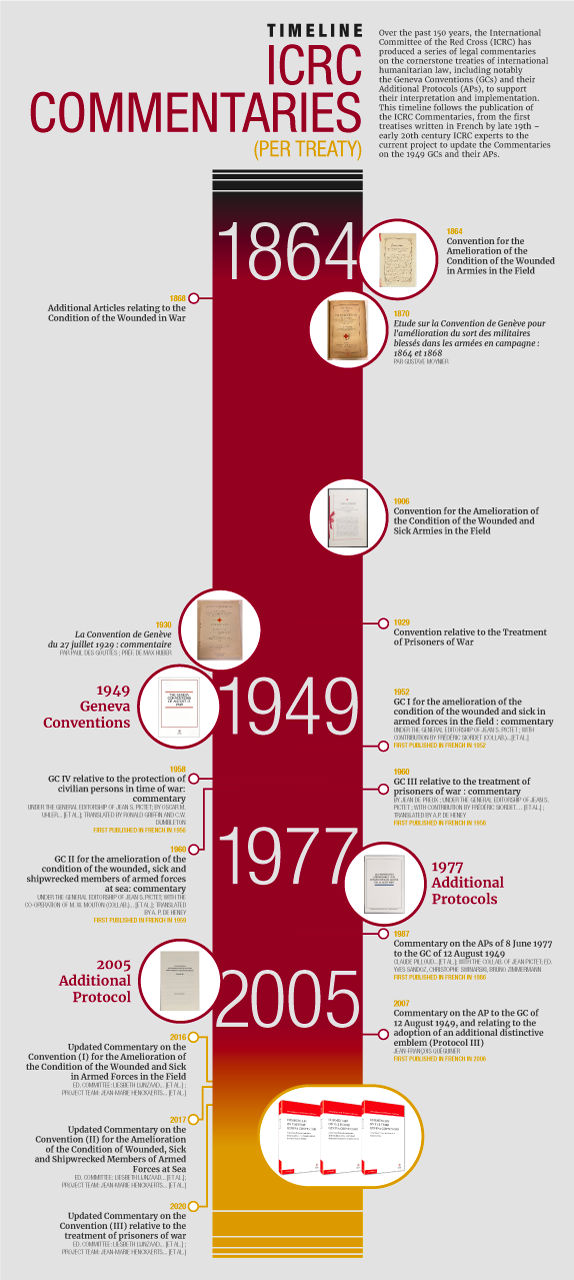

As the guardian of international humanitarian law (IHL), the ICRC has produced many such commentaries explaining the core treaties of this body of law. The updated ICRC Commentaries on the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols are heirs to a long tradition of legal commentaries published to support the interpretation and application of the cornerstone treaties of IHL. This article looks back in time, from the origin of the commentaries to the current ICRC project to update them, to share a few insights on their evolution, in terms of authorship, methodology, audience, form, and substance. How have 150+ years of development of the law and State practice, along with evolving standards for legal scholarship and treaty interpretation, impacted the Commentaries?

The Commentators

The long history of commentaries on IHL treaties can be traced back to 1870, with the publication of a commentary on the first Geneva Convention, adopted six years prior. Since then, the adoption of every new IHL treaty, or revision of an existing treaty, has led to the publication of at least one reference commentary providing an article-by-article interpretation of the law, informed by its drafting history and prior State practice. Most of these commentaries have been written by or under the direction of an authoritative ICRC figure.

In his review essay on commentaries as a genre of international legal scholarship, Christian Djeffal dates their systematization and subsequent proliferation back only to the UN era. “The drafts and treaties produced at diplomatic conferences such as the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907 were not accompanied by commentaries, neither were the attempts to codify international law within the framework of the League of Nations”, he suggests [1]. And so, it seems that, despite the genre’s medieval roots—dating back to the glossators and commentators on the Codex Justinianus—and a strong tradition in German legal scholarship, the pre-WW2 ICRC commentaries on the Geneva Conventions were outliers for their time.

Part of the answer to that mystery may be found in the profile of the author of the very first ICRC commentary: Gustave Moynier. ICRC’s co-founder and president from 1864 to 1910, Moynier was a prolific writer, strongly invested in making his contribution to the birth of the Red Cross and the first Geneva Convention one for the history books. [2] In 1870, he published the aforementioned first commentary on an IHL treaty: Etude sur la Convention de Genève pour l’amélioration du sort des militaires blessés dans les armées en campagne : 1864 et 1868. At the time of publication, the first Geneva Convention had already been applied in a conflict, the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, though only on part of the theater of the war, since three of the belligerents (Austria, the Kingdom of Saxony and the Kingdom of Hanover) were not parties to the Convention. This first test of the treaty’s applicability on the battlefield lead to multiple debates on its revision, culminating with the adoption of additional articles in 1868 extending its principles to maritime warfare. [3] Part legal treatise, part article-by-article commentary on the Convention, Moynier’s 1870 volume is very much imbued with his personal opinions and recommendations for the development of the law. Only after a long introduction resituating the adoption of the Convention within the evolution of mentalities on warfare and human suffering in war did he turn to the textual interpretation of the treaty. His text anchored the Convention in a history of humanitarian progress, quoting Grotius, Vattel and Montesquieu, as a way to stress the treaty’s legitimacy. His interpretation strove to show how the Convention balanced humanitarian concerns and military realities, responding to critics who argued that it was inapplicable on the battlefield. [4]

Why was Moynier best positioned to write such a commentary and put forward an interpretation of the Convention? He asked—and answered—that question himself in the publication: “there was a story to tell”, he explained “and we were in a better position than anyone else to know how things had happened.” [5] His figure loomed large over the early days of the ICRC and the birth of the first Geneva Convention, even if he gave conflicting accounts in his writings over whether he was in fact the main drafter of the treaty. In a letter from 1864, he wrote that fellow ICRC co-founder General Dufour, who had led the Swiss Confederate forces to victory during the Sonderbund War, had produced the “draft concordat” that later became the first Geneva Convention. In 1900, in an article in the Bulletin International des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, he spoke of a joint effort involving General Dufour and himself. In his 1902 autobiography, however, he presented himself as the sole author of the draft. [6]

From 1870 to 2005, commentaries on the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols were published soon after each treaty was adopted, their authors benefiting from proximity in time. They derived their authority as commentators from their legal expertise and familiarity with State practice, but also from their first-hand knowledge of the treaty’s drafting history. The author of a certain treaty’s commentary has in fact quite commonly been one of its main drafters.

In 1906, the report of the drafting committee, presented by renowned law professor Louis Renault, himself the main drafter of the Convention adopted that year, actually functioned as the revised treaty’s commentary. When reproduced in full in the pages of the Bulletin International des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, it was introduced as “the only authorized commentary, (…) which admirably summarizes all the work accomplished”. [7] Two years later, the Swiss Red Cross also published a commentary authored by the former Secretary-General of the 1906 Diplomatic Conference, Swiss law professor Ernst Röthlisberger, a publication celebrated in the International Bulletin. [8]

After the 1929 Diplomatic Conference, ICRC member Paul Des Gouttes was tasked with writing the commentary on the revised Geneva Convention on the wounded and sick, as soon as he had completed the Conference’s report. [9] ICRC president Max Huber explained in his preface why Des Gouttes was uniquely positioned to write the commentary: “Everything pointed to him for this task. As assistant to the Secretary-General of the 1906 Diplomatic Conference and Secretary-General of the 1929 Conference, he followed closely the discussions of both assemblies. In the course of more than thirty years of collaboration with the International Committee of the Red Cross, he had the opportunity to study many questions closely or remotely related to the Convention.”[10]

For the 1929 Convention on prisoners of war, ICRC member Georges Werner—who worked for the International Prisoners of War Agency during the First World War—published in 1928 a study of the draft Convention he had helped prepare, titled simply Les prisonniers de guerre. He was beaten to the publication of the commentary on the adopted Convention by Danish diplomat Gustav Rasmussen, who had attended the 1929 Diplomatic Conference. Werner then reviewed Rasmussen’s commentary in the International Review of the Red Cross, a 20th century example of a practice continuing to this day, in old and new mediums.

The ICRC also collected external commentaries, as well as other types of publications reflecting how States were interpreting and implementing the law. One interesting example found in the ICRC Library’s collections is Dr. Alfons Waltzog’s commentary on the 1907 Hague Convention (IV) on War on Land and its Annexed Regulations and the two 1929 Geneva Conventions, published in the middle of the Second World War. The author worked for the court-martial of the German air force, as Kriegsgerichtsrat. His commentary was addressed to the officers and officials of Nazi Germany. ICRC jurist Werner Christ published quite a scathing review of the commentary in the International Review of the Red Cross, noting “there can be found (…) the reflection of trends in Germany or even of personal opinions, some of which appear to be questionable and which often, in our opinion, deviate from the spirit that inspired the Geneva Conventions.” [11] A typewritten in-house translation into French of Waltzog’s commentary on the 1929 Convention on prisoners of war was also produced, now part of the ICRC Library’s heritage collection on wartime captivity.

The adoption of the four 1949 Geneva Conventions marked, quite logically, a turning point in the history of the Commentaries: they would no longer be a ‘one-man job.’ Under the direction of Jean Pictet, a team of ICRC jurists wrote the Commentaries on the four Conventions, published in French and in English throughout the 1950s. They were Frédéric Siordet, Claude Pilloud, René-Jean Wilhelm, Jean-Pierre Schoenholzer, Oscar Uhler and Jean de Preux. Like Jean Pictet, the first three had worked on the revision of the Conventions and followed the discussions of the 1949 Diplomatic Conference and the earlier expert meetings.

The foreword of the Commentary on the First Geneva Convention draws attention to the genealogy of the commentaries, tracing a direct line from Louis Renault’s 1906 report to the 1929 commentary by Paul Des Gouttes (“who was such a zealous and eminent authority on the Geneva Conventions”) and finally to the present commentary. Notably, this also seems to be the first time that the ICRC resorted to an external specialist: Major M. W. Mouton, naval captain and judge at the Dutch Court of Cassation, assisted in the elaboration of the Commentary on the second Geneva Convention, relative to the protection of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea.[12]

In 1977, the preparation of the Commentaries on the Additional Protocols again mobilized a team of ICRC jurists, this time under the direction of Claude Pilloud. The former ICRC director, who had been Pictet’s right-hand man during the preparation of the Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions, came back from retirement to work on the Commentaries on the 1977 Additional Protocols until his death in 1984. The contributors included Jean de Preux, Yves Sandoz, Bruno Zimmermann, Philippe Eberlin, Hans-Peter Gasser, Claude F. Wenger, Philippe Eberlin, and Sylvie-S. Junod. Most of them had been part of the ICRC delegation to the 1974-1977 Diplomatic Conference. The first woman to author an ICRC commentary, Sylvie-S. Junod wrote the Commentary on Additional Protocol II relating to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts. Her ICRC career spanned over thirty years, both at the organization’s headquarters and as a delegate in Latin America, Uganda, Sri Lanka, Georgia, India and Iraq. Jean Pictet, honorary Vice-President of the ICRC at the time, presided over the reading committee.

The Commentaries on the 1949 Conventions and their Additional Protocols of 1977 had been published in French and English only. In 1998, the Commentary on common Article 3 and Additional Protocol II was published in one volume in Spanish, bringing together a commentary on all articles related to non-international armed conflict. This reflected the increasing importance of the law governing this type of armed conflict which had become the prevalent form of armed conflict. The standalone Spanish translation of the Commentary on Additional Protocol I followed in 2001. [13]

In 2006, ICRC legal adviser Jean-François Quéguiner—who was a member of the ICRC delegation to the 2005 Diplomatic Conference—wrote the Commentary on the newly adopted Additional Protocol III. This commentary was published in the International Review of the Red Cross in French that year, and translated in English, Arabic, Spanish, Chinese and Russian the next. This represented a significant expansion in the target audiences from the previous commentaries produced by the ICRC in English and French only originally, and much later in Spanish.

Quite a few of the ‘usual suspects’ of the ICRC’s history—from Gustave Moynier to Jean Pictet—have thus left their mark on the history of the Commentaries. But, with the development of the law, of State practice and standards for treaty interpretation, there has been a clear evolution towards a more collaborative effort, with the authority of a commentary resting on its authors’ combined expertise and rigorous methodology, rather than the profile of a main author.

In 2011, the ICRC decided to update its Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their 1977 Additional Protocols to take into account the State practice and legal developments that had taken place in the decades since the Conventions were adopted. The goal is to ensure the Commentaries are fit for purpose in contemporary armed conflicts and can serve as a useful interpretive tool for practitioners.

The current project to update the ICRC Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols is the work of many contributors, both internal and external to the ICRC. Some of the authors of the commentaries work on the in-house team dedicated to this project, while others work elsewhere in the ICRC. A number of authors do not work for the ICRC. All the authors of the Commentary on a given Convention are on the reading committee, and thus have an opportunity to give feedback on the commentaries drafted by others. In addition to external authors, there are around 50 external peer reviewers from all over the world for each of the Commentaries — totaling over 120 peer reviewers in total (so far). These are practitioners and academics who ensure that a range of professional specialties and geographically diverse perspectives are represented. Lastly, there is an editorial board to provide guidance and support to the project team, made up of three ICRC legal experts and three external legal experts representing academics, judges and military practitioners. Given all this involvement from legal experts within and outside the ICRC, it is clear that we have come a long way from commentaries that represented the personal opinion of a single jurist.

Their Methodology

Today, commentaries are one of a constellation of types of secondary legal resources. They are different from law review articles or monographs in that they are not meant to be the opinion of an author or authors. They are unlike casebooks or textbooks, which are directed at audiences learning about an area of law, and unlike legal treatises, in that they comment on a specific treaty, group of treaties or other legal instrument, rather than provide a comprehensive understanding of a given area of law. They are also unlike legal manuals published by States, in that they are not implementing the law but rather presenting the reader with research into how the law has been interpreted and implemented. The ICRC Commentaries provide “an article-by-article ‘commentary’ or explanation of the meaning of each provision, its paragraphs, terms, and sentences. For each article, a commentary provides elements for the interpretation of that provision. In addition, a commentary explains the links between articles in a treaty or group of treaties, as well as its links with other rules of international law.” [14] Some commentaries are organized differently, providing an overview of the topics addressed.

The commentaries’ methodology has evolved over time in line with the development of recognized standards for treaty interpretation. Interestingly, some of the principles later codified in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties can already be found in the very early commentaries, introduced as derived from common sense by the commentator. Moynier, for instance, fought back against criticism of the lack of precision of the term ‘force militaire’ in the 1864 Convention by referring to the ‘esprit général’ (general purpose) of the treaty. [15] Paul Des Gouttes would later agree: “the general purpose of the Convention must inform all of its application, even in the details.” [16]

Early commentaries already followed the most common structure of an ‘article-by-article’ explanation of the treaty, dissecting each provision and defining key terms. This textual analysis was—and remains—informed by each treaty’s drafting history, State practice, and, in more recent history, by the practice of international courts and tribunals. In the case of a revision of an existing treaty, commentators also relied on the analysis featured in their predecessors’ commentaries, to pinpoint areas of change and continuity. An element specific to the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols, the commentaries have also systematically been able to draw from the ICRC’s humanitarian activities in armed conflicts. Paul Des Gouttes, for instance, recalled practical examples from the WWI International Agency for Prisoners of War’s history to explain the drafters’ intentions on specific provisions of the revised 1929 Geneva Convention. [17]

The commentaries have thus relied on similar types of sources throughout history. They have also shared a common purpose: to make sense of the treaties and, for each of their provisions, help bridge the gap between the letter of the law and its application in concrete situations.

However, as both law and State practice developed over time, the amount of information to consider dramatically increased, requiring a more systematic and rigorous approach. The First Geneva Convention—the Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field—had 10 articles in 1864 when it was first adopted, 33 after the 1906 revision, 39 after the 1929 revision and 64 (plus annexes) in its final 1949 version. Quite logically, the Commentary’s number of pages almost doubled in size between the 1870 and the 1952 publications, and more than doubled again between 1952 and the 2016 update, from 542 to 1344 pages.

The commentators on the 1864, 1906 and 1929 Conventions list their sources, but are less explicit regarding their methodology. The author’s first-hand knowledge of the treaty’s drafting history would go a long way in asserting the commentary’s reliability. This first changed in Pictet’s era, as he drafted methodological guidelines for the team in charge of the Commentaries on the four 1949 Geneva Conventions. [18] In that document, he stressed the importance of rooting the Commentaries’ analysis in the history of the Conventions, relying on the 1949 Diplomatic Conference’s records and other preparatory works from 1946-1948. He saw as necessary to incorporate in the Commentaries the experiences of past conflicts, especially of the Second World War, to make sense of the addition of new provisions or of the revision of existing ones. Finally, he requested that “although it [will be] a scientific work, the commentary must be clear and accessible to non-lawyers. The style, therefore, must be simple. It will be impersonal and if the author of the commentary has opinions to which he would like to give a more personal touch, he will mark them clearly in the margin.” This was a clear departure from earlier commentaries, in which authors did not hesitate to make their personal point of view known, to criticize or praise the drafters on terminology choices, and to make recommendations for future revisions of the law.

The authors of the ‘Pictet Commentaries’ were basing their work on State practice prior to the negotiation of the Conventions, notably during the Second World War, and several of them were present at the negotiations themselves and could therefore provide first-hand insights into what the drafters were thinking. The methodology behind the updated Commentaries is necessarily different. This once-in-a-generation study/update is based on extensive research and it follows the interpretive tools laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT). According to Article 31 of the VCLT, treaties must be interpreted “in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in light of its object and purpose.” Additional elements that must be taken into account are any subsequent agreements between the Parties to the treaty about its interpretation or application, subsequent practice establishing the agreement of all Parties regarding the treaty’s interpretation (although such unanimous agreement is exceedingly rare for universally accepted treaties like the Geneva Conventions), and other relevant rules of international law that apply in relations between the Parties. This is one, comprehensive approach that must be used as a whole to interpret each treaty provision.

Article 32 of the VCLT refers to supplementary means of interpretation that can confirm or clarify the interpretation of treaty provisions. These include the treaty’s preparatory work, State practice that does not fall under Article 31, the circumstances of the treaty’s conclusion, judicial decisions, and scholarly literature. [19]

Lastly, in accordance with Article 33 of the VCLT, where a treaty has been authenticated in two or more languages, the text is equally authoritative in each language. In such cases, the different language versions of the treaty must be interpreted to be consistent with each other. This means that the equally authentic French and English versions of the Geneva Conventions can be compared to clarify the meaning of terms. This task is even more complex for the Additional Protocols, which are equally authentic in all six official UN languages.

Similar to other recent ICRC publications, the new Commentaries are more open to a diversity of legal positions, and acknowledge alternate legal interpretations where there is no consensus. They are produced in English, but will be translated into the other five official UN languages, reflecting the fact that this is a global conversation that should be open to all.

Their Audience and Reception

Who are the commentaries written for? Leading the ICRC project on updating the Commentaries, Jean-Marie Henckaerts clearly specifies that “as a genre, commentaries are addressed specifically to practitioners and can play a significant role in enhancing compliance. The purpose of commentaries is to clarify the meaning of the norms so that they can be applied in a well-informed and coherent manner.” [20]

Over 150 years ago, when Moynier’s commentary on the first Geneva Convention was featured in Louis-Auguste Martin’s Annuaire philosophique, it was with the latter’s recommendation that his book “be put in the hands of all army and navy officers, and summarized in a few pages for the instruction of the soldier. No one should be able to claim ignorance.” [21] Because the treaty was to be applied during hostilities, its dissemination among decision-makers in governments and in the armed forces was always perceived to be of utmost importance. This most certainly motivated the publication of the early commentaries, as evidenced by their authors’ insistence on the drafters’ realistic grasp of military realities.

In the 1950s, the original ICRC Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions were sent out upon publication to governments (“The International Committee is happy to offer a bound copy of this volume to your Government, and would be grateful if the Ministry of Foreign Affairs could bring this work to the attention of the various Ministries and Services concerned (National Defense, Interior, Health, etc.)” [22]), to the National Societies of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, to selected libraries—like the U.S. Library of Congress and the Bodleian Library in Oxford—and to key academics and international law practitioners, from Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, Erik Castrén, executive director of the Japanese Society of International Law Juji Enomoto, and the International Law Commission. The Commentaries were also sent to a series of law journals. The French edition of the Commentary on the First Geneva Convention, for instance, was sent to fifty-nine journals, including “L’Etat et le droit soviétique” in Moscow, the “Boletim da Sociedade Brasileira de Direito Internacional” in Rio de Janeiro, and the “Annales de la Faculté de Droit” of the University St Joseph of Beirut.

Representing the practitioner’s point of view, U.S. Army Colonel W. Hays Parks presented the so-called ‘Pictet Commentaries’ as “an invaluable reference tool and historical record”, attributing to their editor the “invaluable role of the honest broker.” He summed up their impact in these words: “in the development of any legal advice regarding the 1949 Geneva Conventions, they are the first reference to which one resorts; and more than one meeting or discussion has been shortened by the question, ‘What does Pictet say about this?’ ” [23]. Other experts have similarly acknowledged the weight the Pictet Commentaries have acquired over time. For instance Professors Schmitt and Watts call the ICRC Commentaries “leading sources of clarification and background on the Conventions and Protocols for decades,” going on to say “it is difficult to overstate their influential and nearly authoritative status.” [24] Because of their widespread acceptance, many scholars rely on the Pictet Commentaries as a matter of course, either expressly calling them “authoritative” or without feeling the need to justify the resort to a work of legal literature. [25]

Thus the original ICRC Commentaries have become quite authoritative over time, and in addition to being regularly cited in academic works, have been cited numerous times by various international tribunals, [26] domestic courts, [27] and numerous UN documents such as, for example, Human Rights Council reports. [28] This demonstrates that they serve as a valuable resource, and the hope is that the updated Commentaries will be even more so, as they include many more examples of State practice and refer to diverging viewpoints that may shed light on the law as it has developed since the Conventions were adopted.

The updated Commentaries are not only an academic resource but above all a practical tool for military commanders, officers, and lawyers and other practitioners who must apply the Geneva Conventions, such as judges, legislators, policy makers and humanitarians. They are written in clear language and strive to clarify ambiguity, while leaving room for nuance and acknowledging different schools of thought on how the Conventions should be interpreted.

Despite questions about how the VCLT’s treaty interpretation methodology has been applied, whether the Commentaries go too far to suggest how the law should develop, and many strong reactions to the description of the ‘duty to ensure respect’ contained in Common Article 1, the updated Commentaries have been well–received by the international legal community. As Tania Arzapalo Villón from Peru’s Ministry of Justice and Human Rights says, “In the field of international humanitarian law, especially for actors like us who have the task of promoting its implementation, the Commentaries will give us a solid tool with technical and legal aspects that will facilitate not only the work with the various actors, but also reinforce and improve our work.”

Others have praised the updated Commentaries for their incorporation of a modern understanding of the roles played by women in armed conflict, as well as how detention is carried out during multilateral operations, among other things. As Maj. Gen. Nilendra Kumar points out, “Law is not static or dormant. The facts, interpretation, and applications of law change with the passage of time. This is what makes regular revision of the commentary relevant. It brings out narration and details of new experiences that need to be assessed on the touchstone of the IHL.”

Looking beyond the substance of the criticisms (and praise) that have met the updated Commentaries, what is notable is that the legal context itself has changed. As with other ICRC publications like the International Review of the Red Cross, as the debates among scholars became more sophisticated, the ICRC began to engage more meaningfully with external legal experts. [29] With the advent of blogs and social media, scholars and practitioners worldwide are able to give almost instantaneous feedback, and to engage directly with the project team while the drafting process is ongoing. [30] This is of course also possible at conferences and in other “analog” or “traditional” ways, but new communication tools have enabled this dialogue on a wider scale and in a more inclusive manner. The Commentaries themselves have also been adapted for the digital age; they can be consulted online via the ICRC’s IHL database and IHL mobile app.

Ultimately, exchanges with scholars and practitioners allow the Commentaries to be more accurate and therefore more useful, as evidenced by the addition of new analysis to the commentary on Common Article 1 in the Commentary on the Third Convention to reflect diverging views following intense debate in the legal literature. The fact that more participants are able to engage in these conversations within a shorter range of time means that the process of updating the Commentaries is more dynamic than the drafting of the original Commentaries was. It is not a single legal scholar opining but a network of scholars working together to reflect how the law is being interpreted and applied.

Concluding Remarks

There is a clear continuity in the commentaries’ purpose throughout history. Their methodology, however, has evolved to best fulfill that purpose, in line with the development of the codification of the principles of treaty interpretation and the standards of treaty commentaries as a genre of international legal scholarship.

The ICRC remains in a unique position to put forward such interpretative guidance on the application of the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols. Because of its central role in the development of the law and because of its humanitarian mandate, [31] it has unparalleled access and insight into the history of the Conventions and their application in armed conflict. Today, its jurists base their analysis on the comprehensive records and resources of its archives and library, which document decades of State practice. This all puts the ICRC in a unique position to draw on these records, examine seventy years of the Conventions ‘in action’, and present its findings in a condensed and accessible way.

[1] Christian Djeffal, Commentaries on the Law of Treaties: A Review Essay Reflecting on the Genre of Commentaries, European Journal of International Law, Vol. 24, no. 4, November 2013, p. 1233.

[2] For a more substantial and nuanced take, see Cédric Cotter, The role of experience and the place of history in the writings of ICRC presidents, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 101, no. 910, 2019, pp. 197-215.

[3] The Additional Articles of 1868 were adopted but failed to secure any ratifications and thus never entered into force. Nevertheless, in the Franco-German War of 1870-71 and in the Spanish-American War of 1898 the parties agreed to observe their provisions. It was not before the First Hague Peace Conference of 1899 that a Convention for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention was finally adopted and ratified.

[4] See notably p. 191-196. Gustave Moynier, Etude sur la Convention de Genève pour l’amélioration du sort des militaires blessés dans les armées en campagne : 1864 et 1868, Paris : Librairie de J. Cherbuliez, 1870.

[5] Idem, p. 65 (authors’ translation).

[6] See Ismaël Raboud, Matthieu Niederhauser and Charlotte Mohr, Reflections on the development of the Movement and international humanitarian law through the lens of the ICRC Library’s Heritage Collection, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 100, no. 907/908/909, 2018, pp. 143-163.

[7] Le Comité international et la Conférence de 1906, Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, no. 148, octobre 1906, p. 270-272 (authors’ translation).

[8] Paul Des Gouttes owned two copies, including one dedicated to him by the author, which were gifted to the ICRC Library by his widow after his passing. His 1929 Commentary borrowed one of Röthlisberger’s phrases: “It has been rightly said that an ambulance without its equipment is like a knife without a blade”. Ernst Röthlisberger, Die neue Genfer Konvention vom 6. Juli 1906, Bern : A. Francke, 1908. Reviewed in the Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, no. 155, juillet 1908.

[9] A CICR, minutes of meeting, plenary session of the Committee, September 26, 1929.

[10] Paul Des Gouttes, La Convention de Genève du 27 juillet 1929 : commentaire, Genève : CICR, 1930. Preface by Max Huber, p. XVIII.

[11] Author’s translation, the original quote in French reads as : « On n’y trouve pas l’exposé comparatif des thèses qui se sont fait jour dans les différents pays quant à l’application des dispositions conventionnelles, mais bien surtout le reflet des tendances qui prévalent en Allemagne ou même d’opinions personnelles, dont certaines apparaissent comme contestables et qui souvent, selon nous, s’écartent de l’esprit qui a inspiré les Conventions de Genève », Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 27, no. 316, April 1945, p. 309-310.

[12] A CICR, minutes of meeting, working session, April 30, 1953.

[13] [Yves Sandoz… et al.] ; [tr. del frances por José Chocomeli Lera, con la colaboracion de Mauricio Duque Ortiz], Comentario del Protocolo del 8 de junio de 1977 adicional a los Convenios de Ginebra de 12 de agosto de 1949 relativo a la protecciòn de las vìctimas de los conflictos armados internacionales (Protocolo I) , Comentario […] sin caracter internacional (Protocolo II) y del articulo 3 de estos Convenios, Bogota : CICR : Plaza & Janés, 1998-2001.

[14] Jean-Marie Henckaerts, The Impact of Commentaries on Compliance with International Law, ASIL, Proceedings of the 115th Annual Meeting, 2021, p. 56.

[15] Gustave Moynier, Etude sur la Convention de Genève pour l’amélioration du sort des militaires blessés dans les armées en campagne : 1864 et 1868, Paris : Librairie de J. Cherbuliez, 1870, p. 143-144. « On a été jusqu’à prétendre que les corps sanitaires, classés dans beaucoup de pays parmi les combattants, pourraient être considérés comme une force militaire. Mais cet exemple, par son exagération même, nous rassure au lieu de nous alarmer. Confronté avec l’esprit général de la Convention, ne montre-t-il pas à quelles subtilités inouïes la critique est contrainte de recourir pour battre en brèche un texte qui, s’il n’est pas irréprochable, est du moins fort intelligible et serre d’aussi près que possible la pensée des rédacteurs. »

[16] Paul Des Gouttes, La Convention de Genève du 27 juillet 1929 : commentaire, Genève: CICR, 1930, p. 191 (authors’ translation).

[17] See for example his commentary on article 12, on the return of captured medical personnel. Paul Des Gouttes, La Convention de Genève du 27 juillet 1929 : commentaire, Genève : CICR, 1930, p. 72-86.

[18] Schéma relatif à l’établissement des Commentaires des nouvelles Conventions de Genève. A CICR, minutes of meetings, legal commission, September 14, 1949.

[19] Jean-Marie Henckaerts and Elvina Pothelet, The interpretation of IHL treaties: Subsequent practice and other salient issues, in Heike Krieger and Jonas Püschmann (eds), Law-making and legitimacy in international humanitarian law, Edward Elgar, 2021, pp. 162-168.

[20] Jean-Marie Henckaerts, The Impact of Commentaries on Compliance with International Law, ASIL, Proceedings of the 115th Annual Meeting, 2021, p. 57.

[21] Louis-Auguste Martin, Annuaire philosophique : examen critique des travaux de physiologie, de métaphysique et de morale accomplis dans l’année, Tome VII, Paris : Ladrange, 1870, pp. 357-358.

[22] A CICR, B AG 022 033.03, ICRC circular Fr563b, dated March 16, 1959, for the distribution of the Commentary on the Fourth Geneva Convention in English to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of selected States, from Afghanistan to Yemen.

[23] W. Hays Parks, Pictet’s Commentaries, in Studies and essays on international humanitarian law and Red Cross principles in honor of Jean Pictet, p. 496. The author was then chief of International Law in the office of the Judge Advocate General of the Army, Washington D.C.

[24] Michael N. Schmitt and Sean Watts, State Opinio Juris and International Humanitarian Legal Pluralism, International Law Studies, Vol. 91, 2015, pp. 192–193.

[25] See, e.g., Mao Xiao, “Are ‘Unlawful Combatants’ Protected under International Humanitarian Law?”, Amsterdam Law Forum, Spring 2018, pp. 65, 68; Tatiana Londoño-Camargo, “The Scope of Application of International Humanitarian Law to Non-International Armed Conflicts”, Vniversitas, 2015, p. 210; Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, “Hamdan and Common Article 3: Did the Supreme Court Get It Right?”, University of Minnesota Law Review, 2007, p. 1539; Guanzhu Yan, “Analysis of the Scope of ‘Protected Persons’ in the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949”, Human Rights, 2011, p. 9, n. 5; Alain-Guy Sipowo, “Does International Criminal Law Create Humanitarian Law Obligations? The case of Exclusively Non-State Armed Conflict under the Rome Statute”, The Canadian Yearbook of International Law, 2013, p. 292, n. 12.

[26] See, e.g., ICJ, Armed Activities, Separate Opinion of Judge Simma, 19 December 2005 ; ICJ, Jurisdictional Immunities, Separate Opinion of Judge Cancado Trindade, 6 July 2010 ; ICTY, Vasiljevic, Trial Judgment, 29 November 2002 ; ICTR, Appeals Judgment, Pavle Strugar, 17 July 2008; ICTR, Trial Judgment, Rutaganda, 6 December 1999 ; ICTR, Trial Judgment, Laurent Semanza, 15 May 2003 ; ICTR, Appeals Judgment, Ephrem Setako, 28 September 2011 ; ICTR, Appeals Judgment, Akayesu, 1 June 2001 ; ICTR, Trial Judgment, Stakic, Judgement, 31 July 2003 ; ICTY, Appeals Chamber, Decision on Joint Defence Interlocutory Appeal of Trial Chamber Decision on Rule 98bis Motions for Acquittal, 11 March 2005 ; ICTY, Trial Chamber, Decision on the Defence Motion to Strike Portions of the Amended Indictment Alleging “Failure to Punish” Liability’, 4 April 1997 ; ICTY, Appeals Judgment, Aleksovski, 24 March 2000 ; ICTY, Appeals Judgment, Delalic, 20 February 2001.

[27] See, e.g., USA, Supreme Court, Hamdan v Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense et al, 126 S. Ct. 2749, 2764 (2006), majority opinion, Justice Thomas dissenting, and Justice Alito dissenting ; Republic of Colombia, Jurisdicción Especial Para La Paz Salas de Justicia Sala de Reconocimiento de verdad, de responsabilidad y de determinación de los Hechos y Conductas, Auto No. 19 de 2021, Bogotá D. C, 26 de enero de 2021.

[28] See, e.g., Human Rights Council, ‘There is nothing left for us’: starvation as a method of warfare in South Sudan, UN Doc. A/HRC/45/CRP.3, 5 October 2020.

[29] See Cedric Cotter and Ellen Policinski, A history of violence: The development of international humanitarian law reflected in the International Review of the Red Cross, Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies, Vol. 11, no. 1, 2020, pp. 36-67

[30] See Mikhail Orkin, “In Bruges : The enduring relevance of IHL and the updated Commentaries“, Humanitarian Law & Policy, 23 February 2021; Kelisiana Thynne, “GCIII Commentary Symposium : ‘Preparations Have been Made in Advance’—GCIII and the Obligation to Respect and Ensure Respect by Preparing for Retaining POWS“, OpinioJuris, 27 January 2021 ; Steven Hill, “Geneva Convention III Commentary : Implementing POW Convention in Multinational Operations“, Just Security, 28 October 2020; Keiichiro Okimoto, “The United Nations and the Third Geneva Convention“, EJIL : Talk !, 26 October 2020.

[31] Statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, 1986, Article 5(2).

Comments