In an article published in the International Review of the Red Cross in 2007, Marcel Junod is introduced as the “spiritual father for generations of delegates”[1]. Among all the people who represented the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) across the world, Marcel Junod may be the one that best personifies the figure of the “ICRC delegate”. In his lifetime he accomplished several types of missions such as visiting prisoners of war, exchanging hostages, and delivering food aid. At all times he reflects on his role in the field and the means he has to accomplish his mission, considering the four pillars of ICRC’s activity: protection, assistance, prevention and cooperation. In 1947, he publishes an autobiographical writing Warrior without weapons. The publication of former delegates’ writings is currently very restricted: all ICRC collaborators are bound by a “duty of discretion”, in that extent they are asked not to share writings related to their activities. Warrior without weapons is today considered a “bedside book for every delegate”. Thus, this book occupies a special place within our collections: Marcel Junod’s work is one of the very few delegate’s testimonies that circulated widely. It is also a major document to understand the delegate’s role when in the field.

Table of contents

Childhood – From Geneva to Abyssinia – Spanish Civil War – Europe at war – From Manchukuo to Hiroshima – Warrior without weapons

Childhood

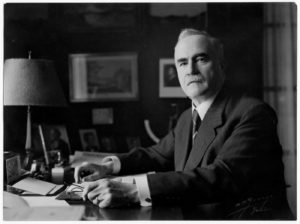

Marcel Junod was born in Neufchâtel in 1904. His father was the pastor in charge of the parish of Chézard Saint-Martin[2]. In 1919, at his father’s death, Marcel and his family went back to Geneva, where his mother came from. As a teenager Marcel Junod took part in the relief movement for Russian children and became more familiar with the humanitarian idea. Marcel Junod was a gifted student: he graduated High School in 1923 and undertook medical studies. In 1929, he received a degree in medicine and decided to specialize in surgery. In the summer of 1929, Junod started as a surgeon in Casablanca. In 1931, he joined the Mulhouse civil hospital where he temporarily replaced the head of the clinic.

From Geneva to Abyssinia

Travelling to Abyssinia

On October 4th 1935, hostilities began between Italy and Ethiopia. In accordance with its mission statement, the ICRC sent a telegram to both Italian and Ethiopian National Societies, asking them if they would like to request assistance from the Movement[3]. The Ethiopian Red Cross rapidly answerd that there was a need for personnel, equipment and money[4]. On the contrary, the Italian Red Cross declined the ICRC’s offer, judging its means sufficient for any eventuality in Eastern Africa.

On October 15th 1935, after four years spent in the Hospital of Mulhouse, Marcel Junod receives a phone call from Geneva. A friend that he met in the “Russian children assistance movement” is asking him to join the ICRC delegation in Abyssinia. Ten days later, Marcel Junod arrives at the villa Moynier, the former ICRC headquarters in Geneva. He tries to understand what his role will be once in the field and looks for additional information in the ICRC library. There he meets Sidney Brown, an ICRC delegate that will accompany him in Abyssinia. This delegate already had experiences with the Red Cross in China and Japan. Answering Junod’s questions, Brown replies that the ICRC will have to provide affected populations with emergency reliefs, look after the prisoners of war and enforce the respect of the Geneva Conventions. Finally, he arouses Junod’s curiosity by mentioning “the Red Cross spirit”. Marcel Junod then meets the President of the ICRC, Max Huber. The President gives him a code of conduct: as a delegate his role will be to alleviate the sufferings of war victims and to “remain objective” at all times.

On November 5th 1935, Marcel Junod and Sidney Brown reach Djibouti. When crossing Suez, they observe the Italian troops’ arrival. During that journey, Marcel Junod realizes for the first time the huge imbalance of strength between the underequipped Ethiopian army and the overprepared Italian troops. When in Addis-Ababa, Junod meets the Ethiopian Red Cross’s administrators to organize all the necessary reliefs. As the Negus troops do not have healthcare services within their ranks, it is a very serious issue.

25 National Societies offer their services to the Ethiopian Red Cross by sending money, equipment, and personnel to Abyssinia. The British, Swedish, Norwegian and Ethiopian Red Crosses provide ambulances, as well as the Egyptian Government. The Swedish Red Cross also sends a small ambulance plane painted with the red cross emblem.

A delegate’s “baptism of fire”

In December 1935, the ICRC receives a telegram from the Ethiopian Red Cross: the message relates how three Italian squadrons bombed the City of Dessie without sparing the Red Cross ambulances nor the American hospital Taffari Makonnen. Marcel Junod is asked to go there to record all the damages. He leaves with six trucks: the journey to Dessie is dangerous, the road is very steep, and the rain makes every movement difficult. Furthermore, Abyssinian bandits, the “Chiftas”, represent a danger for the convoy: Junod decides to install watchmen on the trucks’ roofs and carries a Winchester at all times. When in Dessie, Junod receives a very warm welcome, but he can see the overall extent of the damage: “The next day one of the counsellors of the Emperor conducted me on a tour through the ruins of Dessie. The acrid odour of burning still rose from the rubble. All that was left of the stone houses were the scorched walls. The thatched huts were just heaps of charred cinders.”[5] This bombing engenders new fears: could Red Cross ambulances be targeted ? Junod investigates the bombings, interrogates witnesses and examines the damages. He comes to the conclusion that the Italians were trying to hit the Emperor’s headquarters, but by mistake bombed the American hospital.[6]

A few weeks later Marcel Junod goes to the city of Weldiya in Northern Abyssinia and meets an Ethiopian ambulance. There, he witnesses a strange event: as an Italian plane shows up, nurses instantly camouflage their ambulance and hide their tents and equipment with brushwood. The injured try to run away as fast as they can: the fear of an air attack has now taken hold within the Red Cross units.

By the end of the year, this situation repeats itself. Junod goes to Dessie at the request of the Emperor. There, he is told about a very serious incident in the Melka Dida area: the Swedish Health unit has been bombed and the ambulance chief is badly injured. Travelling through great dangers, Junod finally reaches the site of the bombings. He notices that the health unit was intentionally destroyed, as it was located far from the combat zone, and covered with the red cross emblem. The Italian air force states that the Ethiopian army was making use of the red cross emblem to hide military positions: the Swedish Red Cross ambulances were in fact chosen as targets in acts of vengeance after the capture and death of an Italian aviator.

In December 1935 and January 1936, the Italian government reported several cases of misuse of the red cross emblem. In October 1935, the royal Legation of Italy in Bern had already indicated that Abyssinians authorities misused the red cross emblem. On the 16th of January 1936 the Italian government expressed their wish to have ICRC delegates in the field ascertaining the respect of the Geneva Conventions. On the Ethiopian side, no objections were made against the presence of ICRC delegates. For the first time, the article 30 of the Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 27 July 1929. is invoked.[7]

“At the request of a belligerent, an investigation must be held, in such manner as shall be agreed upon by the interested parties, concerning any alleged violation of the Convention; whenever such a violation is proved, the belligerents shall put an end to it and repress it as promptly as possible”.[8]

The ICRC makes the required preparations and ask the Ethiopian government to designate a plenipotentiary representative. In the field, Marcel Junod is in charge of letting the Ethiopian government know the conditions under which the Italians think an investigation can be launched.

In February 1936, fearing the Italian air strikes, several ambulances decide to “work under cover”. Marcel Junod tries to rejoin the Emperor and his staff near Dessie. For the first time, he is confronted with chemical warfare:

“Men were stretched out everywhere beneath the trees. There must have been thousands of them. As I came closer, my heart in my mouth, I could see horrible suppurating burns on their feet and on their emaciated limbs. Life was already leaving bodies burned with mustard gas.”[9]

The Comte of Rosen, a Swedish aviator, in front of the plane of the Ethiopian Red Cross (A CICR(DR))

In fact, by this time Junod had already seen a patient that suffered from chemical injuries. This patient had been taken to him by the Ethiopian commandant Ras Desta. At that time, Junod did not believe in chemical burns and thought that the tissue swelling he saw was due to poor blood circulation.[10] For a long time Junod remained skeptical on the use of chemical weapons by the Italians. On March 17th 1936, when the Italian air force bombed the Red Cross plane that Junod and the comte Von Rosen were trying to protect, he smelt for the first time the odour of mustard gas. Once back in Addis-Ababa, Junod sent a telegram to Geneva reporting his observations. It took him a rather long time to realize how harmful toxic gas were: until April 1936 Junod was still certain that no death resulted from a gas attack.

“Being the ICRC representative” in Abyssinia

As a delegate, Marcel Junod must ensure effective liaisons with Geneva. All along his mission he writes and sends reports to Geneva. One of these reports draws the League of Nations’ attention:

“[…] the Comité des Treize at its meeting this morning, instructed me to ask the International Committee of the Red Cross whether it was possible to give the Comité information communicated by officials of the International Committee of the Red Cross, or personalities such as those of the doctors of the ambulances of the Red Cross in Ethiopia, concerning the breaches of international conventions on the conduct of war signed by the two belligerents.

The Comité des Treize was informed in particular that the International Committee of the Red Cross must be in possession of a report by Dr Junod for the month of March, as well as a report written by the doctors for the Swedish ambulance in December.

I would be very grateful if you could send me your reply as soon as possible, since the Comité des Treize is to continue its work this very afternoon.” [11]

In fact, being a neutral institution, the ICRC cannot pass on reports written by the delegates to other institutions. For this very reason, the ICRC replies to the League of Nations saying that, as the investigation is still ongoing, no documents can be disclosed to the public. The ICRC underlines that the principle of neutrality prohibits the disclosure of such documents as a rule.

This confrontation between the ICRC and the League of Nations illustrates the existing pressures on Junod’s work in Abyssinia. When, after Dessie’s bombing, Sidney Brown declares that “Italians have no excuses”, he and Junod are reminded of their obligation to remain neutral.

For more information on Junod’s mission in Abyssinia

Archives

- Series ACICR BCR 210-134 : Mission reports and correspondance Ethiopia 1935-1936

- Report of March 1935 on the bombing of the Red Cross campaign hospital of Melka Dika.

Filmed archives

- 1935 : le CICR durant la guerre italo-éthiopienne (© CICR/08.2015/V-F-CR-F-01450)

- Red Cross unit bombed in Ethiopia (© Universal Newsreel/1936/V-F-CR-H-00045)

Primary sources

- Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, Rapport du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge sur le conflit italo-éthiopien et la Croix-Rouge, Genève : [CICR], Décembre 1936

- Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, Circulaires du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge : [Circulaires 319 à 325], Genève : CICR, 1935-1936

- International Committe of the Red Cross,General report of the International Red Cross Committee on its activities from August, 1934 to March, 1938, Geneva : ICRC, 1938

Reference work

- Rainer Baudendistel, Between bombs and good intentions: the Red Cross and the Italo-Ethiopian war, 1935-1936, New York ; Oxford : Berghahn, 2006

Articles and chapters

- Rainer Baudendistel, « Force versus law : the International Committee of the Red Cross and chemical warfare in the Italo-Ethiopian war 1935-1936 », International review of the Red Cross, Vol. 80, no. 829, march 1998, p. 81-104

- Carl J. Burckhardt, «Das internationale Komittee vom Roten Kreuz im abessinischen Konflikte», in Vorwort E. Grossman Vom Krieg und vom Frieden : Festschrift der Universität Zürich zum siebzigsten Geburtstag von Max Huber, Zürich : Schulthess, 1944

Another type of conflict: civil war in Spain

In July 1936, Junod is back in Geneva to report on his mission in Ethiopia. Now, Europe is shaken by a new conflict: a civil war as broken out in Spain. At the time, this type of conflict did not have a legal framework as important as the one existing for inter-State conflicts. The 14th resolution of the Xth International Conference of the Red Cross (1921) notes that:

“The 10th International Conference of the Red Cross gives the International Committee of the Red Cross the mandate to intervene in relief work in the event of civil war”[12]

The Conference then insisted on the fact that a civil war could not justify violations of the right of people. Overall the Conference pointed out two main concerns: hostage taking, and detention in time of civil war. Both those concerns are major issues that Marcel Junod will face during his time in Spain.

“Exchange of hostages”

On August 29th, Marcel Junod is in Barcelona. On the road, he meets the spokesperson for Catalonia and tells him he fears hostages could be executed. Junod then reaches Valencia after meeting no less than 148 checkpoints. After arriving in Madrid he meets José Giral, the President of the Ministries Council. José Giral is committed to the ICRC and gives his consent to the exchange of hostages. He also allows women and children to leave the Republic’s territory if necessary. On the contrary, Junod faces the hostility of the Nationalists he meets in Burgos a few days later when he discusses the same issue. General Mola even ask how Junod could “expect us to exchange a caballero for a red dog?”[13]. Junod nevertheless manages to reach an agreement with both sides. He also accepts to recognize the nationalist Red Cross of Burgos.

On the 3rd and 15th September 1936, Marcel Junod, on behalf of the ICRC, arranges four agreements. The first two agreements deal with the Spanish Red Cross and the Republicans: two delegations will be sent to Spain. One will work from Madrid and Barcelona, when the other will work from Burgos and Sevilla. The two last agreements are arranged in Burgos with the Junta: the nationalist Red Cross is to give whole support to the ICRC in its work. The Junta also declares that the Geneva Conventions shall be respected, and that civilian hostages could be exchanged.[14]

Junod becomes the head of the delegation working on the Republican side. He manages to exchange two hostages: Don Esteban Bilbao, a Carlist, former member of the Parliament, and Ercoreca, the socialist mayor of Bilbao. The exchange is hard to negotiate as no one wants to make the first move, and as at any moment a party to the conflict can renege on its commitment by not delivering their hostage.

This situation happens in September 1936 when the nationalists of San Sebastian ask for 130 women, detained in Bilbao, to be taken back to their families. Junod tries to organize the exchange and finds assistance with the British consul. He introduces Junod to the Commandant Burrough. The detainees will transit on his boat, the Exmouth.

“You’re a bit like Mickey Mouse. […] You keep your eye on the Spanish scales: one side white and the other side red. When one side tips down you immediately hop on the other to restore the balance.

“That’s more or less it […] When ten people are condemned to death on one side I try to find ten on the other and arrange an exchange. In that way I succeed in saving twenty lives.”.

“Marvellous […] Well, when are we going ?”

“Tomorrow, for Bilbao.” [15]

The Basque people let the women go with Junod. As they arrive in San Sebastian, there is great emotion, but no counterpart is offered. Junod fears he has been fooled. He faces huge difficulties as he tries to compel the nationalists to set free 130 hostages. Junod multiplies initiatives to make the nationalists keep their word. Yet, their reluctance does not fade and Junod is even called a “renegade and miserable idiot” by a Phalangist newspaper published in San Sebastian. A smear campaign is launched against him, and he is called a “high dignitary of universal Freemasonry”.[16]

“Exchange of messages”

The ICRC delegations in Spain endeavor to put together a Tracing Agency by setting up a system of “news cards”. These documents allow families to get information about their relatives. During this conflict, more than 5 million “news cards” would eventually be exchanged. The families’ distress is a real concern for Junod: he obtains from the Governments of both Madrid and Burgos commitments to respect the 1929 Geneva Conventions. Junod is authorized to set up a Tracing Agency for prisoners of war and civilian prisoners. This Tracing Agency is under the control of the ICRC delegates working in Spain. In the beginning, the Red Cross card is a small summary of messages that couldn’t be transmitted. But very soon this card becomes a “marvelous method of communication able to traverse all barriers.”[17] This document enables civilians to get in touch with relatives living in the opposing zone. It plays a very important role during the Spanish Civil War and contributes to the Tracing Agency’s success. On this occasion, the ICRC realizes how efficient this system is. The Tracing Agency is also a way to gain access to prisoners and detainees whose trace had been lost. In Bilbao, Junod and Daniel Clouzot manage to visit three boats where non-combatants are kept prisoners.

“Saving the lives of those condemned to death”

In early 1937, Marcel Junod is asked to go back to Valencia. There, he tries his best to organize exchanges between prisoners condemned to death, preparing lists of hostages that could be exchanged. One of them will eventually contain up to 2000 names. Having one’s name on a list does not mean that an exchange will immediately happen, but it could nevertheless suspend the execution of a death sentence. These negotiations are perilous and must be carried out with great care: at the slightest break, at the first shot, the negotiation tank. Arthur Koestler, journalist for the News Chronicle, recalls in his book, Spanish Testament, how Marcel Junod saved his life by exchanging him with the wife of a pro-Franco aviator.

From his experience in Spain, Marcel Junod is called upon to train future delegates. Raymond Courvoisier, recalls a speech given by Marcel Junod to young delegates:

“It should never be forgotten that the ICRC’s action is essentially a humanitarian relief action, and that it must inspire complete moral security in all circumstances and in all places. On this commitment, and on its respect, depends whether relations with the belligerents are marked with confidence.

To this end, an ICRC delegate should work with absolute selflessness. He should remain resolved never to serve, even indirectly, the interests of some at the expense of others. He will confine himself to be the neutral intermediary between the parties or the national societies in conflict. A delegate should limit himself to noticing and then acting, as soon as he can, the best he can. He has no other mission than to prevent and alleviate the suffering of war victims, military or civilian. He protects the lives of men, their health, and upholds the rights of the human person. His mission in this sense is universal. He does not have to look for the origin of a conflict, a massacre or an isolated act, nor to judge what happened. If he looses his objectivity, he becomes a judge, he is no longer neutral. […]

The Geneva Convention, as you all know, concerns the military, whether wounded or prisoners, as well as civilians, whether they are in occupied territory or in enemy territory. However, everything suggests that these texts need to be updated. We are working on this in fact. The future is bleak for Europe. Germany and Italy are less and less hiding their aggressive ambitions. In Spain, the civil war has been raging since last spring. What is happening in the Iberian Peninsula suggests the worst for this country.” [18]

Following his experience in Spain, Junod writes a report entitled Future work for ICRC delegates. In fact, Junod has had quite an important influence on the ICRC philosophy and doctrine as he noted that the delegates should be “impartial observers in a civil war that cannot be considered any longer a military rebellion”. In 1961, at Marcel Junod’s funeral, Léopold Boissier recalls that the Spanish Civil War was one of the conflict that influenced Junod the most in his work[19]. In that extent, Boissier indicates that a delegate does not only help the victims of armed conflicts. A delegate reports his experiences to Geneva, makes observations and draws attention on the needed improvements in international humanitarian law.

For more information on Junod’s mission in Spain

Archives

- ACICR 212 57-6 et 61-64 : Reports of Marcel Junod to the Spain commision and correspondance 1936-1939

- ACICR BCR 212 : letter from Marcel Junod to the ICRC on the 26th of December 1936

- Report to the Spain Commission in Geneva (10th of November 1936)

Primary sources

- International Committe of the Red Cross,General report of the International Red Cross Committee on its activities from August, 1934 to March, 1938, Geneva : ICRC, 1938

- Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, Circulaires du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge : [Circulaires 329 à 335], Genève : CICR, 1936-1937

- Arthur Koestler, Spanish testament, [S.l.] : Victor Gollancz, 1937

Reference work

- Pierre Marqués, La Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre d’Espagne (1936-1939) : les missionnaires de l’humanitaire, Paris ; Montréal : L’Harmattan, 2000

Articles and chapters

- Richard Deming, « Chapitre IV : Marcel Junod, doctor on leave », in Heroes of the International Red Cross, Geneva : ICRC, 1982

- Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, « Comité international : chronique mensuelle [février 1939] », in Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no 242, février 1939, p. 135-137

- Georges Patry, « Visite aux prisonniers et aux réfugiés espagnols dans la région de Perpignan », Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, no 242, février 1939, p. 87-97

- For more information on the ICRC audiovisual collections related to the Spanish civil war, please read the Damian Gonzalez’s article, La guerre d’Espagne (1936-1939): déploiement et action du CICR en images

Europe at war

As the Second World War begins, Junod reflects on the industrialization of warfare: as the world is facing new means of destruction, what can be the role of ICRC delegates?

“What was to become of the inhabitants of towns destroyed from the air by concentrated bombing such as we had already seen in Poland? And what, above all, was to happen to the populations of occupied countries, handed over without any protection, without the guarantee of any Convention, to the mercies of the conqueror?”

“All that would now be outdone ten times, a hundred times. We knew all that, and we might have been excused if we had felt overwhelmed by the magnitude of our task.” [20]

Investigations in Poland

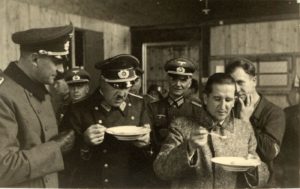

On September 15th 1939, Marcel Junod leaves Geneva: he is in charge of establishing a contact with the authorities in charge of prisoners of war and civilian internees. Junod also tries to get in touch with the German Red Cross in order to set up a delegation in Berlin. On this occasion, he visits several prison camps such as the Hammerstein camp on September 26th.[21] During his mission he manages to obtain a list of important elements on the way prisoners of war and civilians internees are treated. Marcel Junod is also sent to Poland to carry out an investigation: Berlin wants the ICRC to come and see assassinations allegedly committed by Poles in the region of Posen and Bromberg: “ We were informed that reports from Posen and Bromberg in Western Poland, which had just been conquered by the Wehrmacht, showed scores of cases in which German civilians had been murdered by the Poles before their retreat. I was requested to go there and take note of these atrocities on the spot.”[22] The ICRC accepts Berlin’s request but insists on the fact that Junod’s testimony has to remain confidential and that it should not be published in the press nor used in any official document. Junod arrives at Posen and attends the autopsy of several bodies, but testimony is lacking, and the information given is biased. Worse still, his visit makes the front page of a Danzig newspaper[23]: Junod is scandalized and refuses to continue the investigation unless he is allowed to visit other prisoners of war. He finally obtains permission to visit other camps. These visits remain fairly superficial, especially since throughout his visits and investigation Junod is accompanied by a young diplomat and an officer of the Wehrmacht.

In November 1939, Marcel Junod visits prisoners of war in Germany.[24] During this journey, he reaches Poland and asks to go to Warsaw. The path is difficult, and the landscape is devastated. As he arrives in Warsaw he sees a ruined city where “crowds of miserable, trembling and hungry people wandered.” Junod observes the Polish population’s difficult living conditions, and reports to the ICRC the existing restrictions targeting Jewish populations. Junod meets the President of the Jewish community, Adam Czerniakow, who is in charge of the organization of the ghetto . He promises him medical help and food supplies. Finally, Junod visits hospitals, typhoid fever takes its toll and the coming winter suggests the worst.

In the spring of 1940, a small ICRC delegation of 5 people is established in Berlin. It is then chaired by Dr. Roland Marti, and Marcel Junod, itinerant general delegate. In April 1940 Denmark and Norway are invaded by Nazi Germany: Junod then goes to these two occupied countries and visits the British prisoners of war. [25]

Departure for France

In June 1940, Marcel Junod is called by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for an interview: there, he is told about a rumor accusing the French of shooting German paratroopers, violating the Geneva Conventions. Junod needs to go to France to verify this information. But the road to the French authorities is very difficult: Paris is occupied on June 14th, and France is in a débâcle. Junod needs to get in touch with the French authorities: he leaves Geneva with Claude Pilloud and tries to reach Bordeaux where the French government has fled.[26] The situation is chaotic. Once in Bordeaux, Junod manages to meet Louis Colson, the Minister of War. He gives Junod all necessary authorizations to visit prisoners and internees.

The armistice is signed, on June 22nd. As the German army is advancing, the exodus of the French population creates an unexpected situation. This time it is not the families who lose track of their relatives put in prison, but the prisoners who lose track of their fleeing families. Junod tries to reconsider the organization of the Central Tracing Agency. Henceforward, prisoners of war will address their capture cards to the Central Tracing Agency in Geneva, then the Agency will trace the family and send the corresponding card. Berlin agrees with this system. On the French side, Junod needs to go and meet Philippe Pétain[27] to obtain an agreement: cards will be at the disposal of the French families who will be able to send requests to the Central Tracing Agency in Geneva.

Blockade and food supply

In 1941, Marcel Junod and Lucie Odier, another ICRC delegate, travel to London to meet the British Admiralty. They aim to obtain the authorization for Red Cross ships to navigate freely. The Red Cross ships would benefit from “navicerts”, that is, safe-conducts distributed by the belligerents to merchant ships. This way the Red Cross would transport food and clothes parcels to the prisoners of war kept in European harbours. This audience with the British Admiralty leads to the creation of an important sea route for the transport of relief between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

In Summer 1941, Greece finds itself in a dramatic situation: the country is occupied by the German, Italian, and Bulgarian armies. The British blockade in the Mediterranean Sea and a very cold winter create a decrease in yield exposing the Greek population to famine. Through humanitarian diplomacy the ICRC seeks to send large quantities of food to the Greek population. The strategy chosen by the ICRC is therefore based on two approaches: on the one hand it seeks to meet and have a discussion with the different governments, on the other hand it seeks to publicize the fate of the Greek population to generate a surge of generosity in its favor. In that extent, Marcel Junod is given a series of pictures of starving children:

“I was about to leave for Geneva, and was strapping up my cases when a young woman was announced. It was Amelita Lycouresos, a Greek nurse who was in charge of the distribution of milk for the infants. On my table she placed two green files. There were no reports inside but a hundred photos, each complete with exact details. The camera had been at work in the children’s homes, in the distribution centers and in the hospitals, and the result was a series of pathetic pictures of small stunted and deformed bodies of children it was difficult to believe were still alive.”[28]

This nurse is in fact Amalia Lykourézou. She represents the Near East Foundation (NEF) in Greece and works for the Hellenic Red Cross as Head nurse. The pictures were probably taken secretly by Voula Papaioannou as the occupying armies prohibited photographers from entering hospitals[29]. By giving these pictures of starving children to Marcel Junod, Amalia Lykourézou hopes to catch the attention of donators on the terrible situation faced by the Greek population.

“At the mixed commission assembled in Geneva of members of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the National Red Cross Societies horrified faces bent over the photos I had brought with me. The diplomats were shown them too.”[30]

According to Junod those pictures played a decisive role in attracting donations. These documents circulated widely in an article published in the International Review of the Red Cross in August 1942.

Visiting prisoners of war in Germany

Junod returns to Berlin in 1942. Upon his arrival, he is arrested by the Gestapo on suspicion of spying for the benefit of the French. The situation is not easy: the ICRC has obtained that 5 or 6 delegates could visit prison camps in Germany. One more delegate is staying in Athens. In Belgrade and Paris two correspondents represent the Committee. No other delegate is admitted in the occupied territories.

On several occasions Junod enters prisoners’ camps. During one of his visits he realizes the massive difference of treatment prisoners of war face according to whether or not their country has signed the Geneva Convention. If his visit to the British prisoners in the camp of Doessel seems rather reassuring, the visit to the Russian prisoners is, on the contrary, very alarming.

“Affixed to the walls of the huts in the Oflag for British officers was the text of the Geneva Convention, known to all and respected by the prison-camp authorities. In the huts where the Russians were kept the walls were bare.

On the one hand the prisoner was respected, and his affairs were discussed calmly and objectively, and on the other the whip lash descended on his back.”[31]

In this conflict reciprocity is a recurring problem: parties to the conflict sometimes refused to respect the Geneva Conventions under the pretext that their opponents were not respecting it already. The fact that USSR had not signed the Geneva Conventions at the time was used to justify the terrible treatment of Soviet prisoners. In fact, Junod made an attempt to negotiate with the Soviets in Ankara in order to make them implement the Geneva Convention, but nothing came of the negotiations. Junod also met General Reinicke and asked him if the Geneva Convention could apply to Soviet prisoners in the Reich. Unfortunately, as this issue was very politicized, no decision was ever made in that direction.

For more information on Junod’s missions in Europe

Archives

- ACICR, C SC, RR, vol 1-2-3, : Marcel Junod’s reports in Poland

- ACICR G 59/8 : Archives related to evacuations in the Reich 1942

Primary sources

- Comité International de la Croix-Rouge, « Œuvre de secours en faveur de la population civile hellénique », Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 24, no 284, août 1942, p. 570

- Marcel Junod, “Conférence du Dr Marcel Junod“, in Revue internationale de la croix-Rouge, Vol. 25, no.292, p.268-275

Articles and chapters

- Daniel Palmieri and Fania Khan Mohammad, « Des morts et des nus : le regard du CICR sur la malnutrition extrême en temps de guerre (1940-1950) », in Renée Dickason, Mémoires croisées autour des deux guerres mondiales, Paris : Mare & Martin, 2012

- François Bugnion,”The conflicts in Eastern Europe”, in The International Committee of the Red Cross and the protection of war victims, Genève, CICR, 2003, p. 186-190

From Manchukuo to Hiroshima

From 1943 to 1944, Junod is exhausted. He comes back to Geneva for one year and temporarily leaves the ICRC. He works at the Swiss Society for insurance against accidents and occupational diseases. The President of the ICRC, Max Huber, writes him the following words:

“Dear Doctor, you have been for 7 years one of the most faithful servants of the Red Cross. Always on the go, ready to leave for distant lands, in often difficult and sometimes perilous conditions, you have never refused your assistance.

In Africa, in Spain, during the war in Europe, you have successfully accomplished many important and difficult missions. Your qualities and energy have made you overcome many obstacles and have enabled you to render outstanding service to the Red Cross.

[…] The fact that you would be good enough, if we use you in the coming months and later, to continue to provide us with some collaboration, insofar as your professional obligations allow it, is very pleasant to us. We are happy to be able to count on your dedication and I thank you for it.”[32]

By the end of year 1944, Junod returns to the ICRC‘s headquarters in Geneva.

Mission in Manchukuo

In June 1945, Marcel Junod and Margherita Straelher, another ICRC delegate, are asked by the ICRC to go to Japan. As the Japanese refuse to admit people coming from an enemy territory, the delegates must renounce to go through the United States on their way to Japan. Instead, they depart eastward: “Cairo, Teheran, Moscow, Siberia and Manchukuo”. The journey across the USSR is very long: it takes the Trans-Siberian train nine days to cross the 5,000 kilometers separating Moscow from the Manchu border. On July 19th, Marcel Junod and Margherita Strahler arrive in Tchita to catch the Trans-Manchurian train. Time is of the essence, Junod fears that the USSR will declare war to Japan before they can reach Optor, a town at the border of the USSR and Manchukuo.

Japan did not ratify the 1929 Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War. This is a real complication for the ICRC: beside the fact that the ICRC cannot access the prisoners and internees detained in Japan, gaining access to information about their fate is almost impossible.

As they arrive in Manchukuo, Junod and Straelher head to Moukden and Seihan. In fact, they are looking for two high-ranking officers: general lieutenant Arthur Ernest Percival and General Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright. Marcel Junod and Margherita Straelher are under constant surveillance and they face many difficulties when they ask about the prisoners’ conditions of detention. Every detail of their visit is organized beforehand and very little time is left to the visit of prisoners of war. The delegates never meet all the prisoners and it seems to be forbidden for the detainees to talk to them. Despite all that, Junod and Straelher manage to exchange a few words with General Wainwright and General Percival.

Arrival in Japan: bombings and first rumors

On August 9th, Marcel Junod and Margherita Straelher arrive in Japan. The same day the USSR declares war to Japan and the United States Air Force drops an atomic bomb on the town of Nagasaki. Three days before this, a first atomic bomb was dropped on the town of Hiroshima. On August 15th, Japan surrenders to the Allies. Junod tries his best to ensure the safety and evacuation of the allied prisoners kept in Japan. He takes on extra staff in order to reinforce the ICRC delegation in Tokyo. Camps of prisoners that have been hidden, are finally discovered. As Junod enters Omori camp where 200 allied aviators were held prisoners, he is appalled by the terrible treatment they received: “At least a quarter of these men were not ill, but dying”. He gets in touch with the United States Navy. On August 27th, Junod submits a plan to the Americans and organizes the evacuation of the allied prisoners.

In parallel to these evacuation operations, Junod asks one of his colleagues, Fritz Bilfinger, to go to Hiroshima. Up to that moment Junod has faced many difficulties to obtain reliable information on both atomic bombings. On the American side, the High-Command prevents the diffusion of information; on the Japanese side, no information is made public either. Rumors describe the bombing as a “typhoon of glare, heat and wind which had swept suddenly over the earth and left a sea of fire behind it”. On August the 30th, Bilfinger sends back a telegram to Junod :

“6 Suzuki for Junod STOP visited Hiroshima thirtieth conditions appailing STOP city wiped out eighty percent all hospitals destroyed or seriously damaged inspected two emergency hospitals conditions beyond description FULLSTOP effect of bomb mysteriously serious STOP many victims apparently recovering suddenly suffer fatal relapse due to decomposition of white bloodcells and other internal injuries now dying in great numbers STOP estimated still over onehundredthousand wounded in emergency hospitals located surroundings sadly lacking bandaging materials medicines STOP please solemly appeal to allied high command consider immediate airdrop reliefaction over center city STOP […]”

On September 1st Junod finally receives pictures taken in Hiroshima: the documents make public the incommensurable sufferings caused by the atomic bomb. Junod meets Generals Wainwright and Percival, General Fitch, Cl Marcus, and General Farrell. On September 4th, he sends a formal demand to the High Command to organize a relief operation. General MacArthur agrees with his request and lets him organize this operation.

“The Hiroshima disaster”

On September 8th 1945, Junod flies to Hiroshima with a commission of American experts. From the plane, he observes a very strange landscape:

“The centre of the city was a sort of white patch, flattened and smooth like the palm of a hand. Nothing remained. The slightest trace of houses seemed to have disappeared. The white patch was about 2 kilometers in diameter. Around its edge was a red belt, marking the area where houses had burned, extending quite a long way further, difficult to judge from the airplane, covering almost all the rest of the city. It was an awesome sight.”[33]

As he arrives in Hiroshima, Junod meets Masao Tsuzuki[34], a Japanese professor whose research focuses on the effects of radioactivity on living beings. Junod’s testimony is important as he is one of the first western doctors to discover a city in which an atomic bombing took place. For five days he remains in Hiroshima, visits hospitals and looks after the distribution of medical supplies. As a doctor, he takes part himself in the care given to the victims. Marcel Junod wishes to share his observations with the ICRC but also with the widest audience possible. Taking inspiration from the communication campaign organized to help the Greek children, Junod tries to obtain pictures of the city and the victims. He aims to publish a leaflet showing the terrible consequences of atomic bombings. Unfortunatly, on September 19th, General MacArthur applies military censorship to the information related to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Jumod’s testimony is finally published in 1982 in an article in the International Review of the Red Cross: The Hiroshima disaster. This document develops some of the aspects described in Warrior without weapons. It adds many medical indications on the effects of the bombings. It focuses on the work done by a unit from the Imperial University of Tokyo in charge of the military hospital of Ugina. Following these observations, Junod distinguishes four categories of effects : the first effect is a burning by ultra-violet radiation also called flash burn ; the second effect is thermal, the heat generated by the bomb causes severe and deep burns ; the third effect is mechanical, it is the blast wave of an explosive bomb, except this time it is “infinitely greater than anything the world has seen before”. The last effect is radioactivity: Junod describes the symptoms of what he calls “Hiroshimitis”, that is, the disease caused by an irradiation. As he describes the symptoms of the irradiation, Marcel Junod tries to give a very precise idea of all the consequences of the bomb on the population of Hiroshima.

As a conclusion, he asks two questions:

“What new factors in warfare does the atom bomb bring to bear?

Is there any possible defence system to protect civilians from similar attacks?”

Junod answers the first question by noting that this new type of weapon does not respect the principle of distinction. As its explosion releases so much energy, the bomb extends its action over kilometers. Medical teams and public services have been affected. In addition, persistent radioactivity endangers the rescue teams.

Marcel Junod answers the second question from a historical perspective. He recalls that the experiments held in the atoll of Bikini were showing “even more terrifying consequences”. He also remarks that trying to find a protection seems to be derisory when confronted to this type of weapons: “for someone who was a witness, albeit one month later, of the dramatic consequences of this new weapon, there is no doubt in his mind that the world today is faced with the choice of its continued existence or annihilation”. Junod draws a comparison with the use of poison gas during the First World War:

“After the war, the various nations, horrified by the effects of this poison, signed a convention banning the use of this gas forever in future armed conflicts. This commitment was upheld during the Second World War, to the credit of humanity. […][35]

Only a unified world policy can save the world form destruction. State leaders should follow the example of doctors and scientists, who come together at congresses to share the benefits of discoveries and new ideas with their colleagues. The world would then have the peace of mind it longs for”.[36]

As Junod played an important role in bringing relief to the affected population, he remains an important figure for the city of Hiroshima. In 1979, a monument is dedicated to him in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Nuclear weapon, IHL development and the ICRC position

In September 1945, Max Huber notes that during the Second World War, the “increased effects” of bombings have badly affected the principle of distinction between civilians and combatants. According to him, the destructive potential of nuclear weapons might worsen this tendency.[37] The ICRC questions the legality of these weapons and calls on States to find an agreement prohibiting their use. It is the beginning of a lasting engagement on the issue of nuclear weapons. The main argument against the use of these weapons concerns their failure to respect the principle of distinction between civilians and combatants. This argument was regularly presented during International Conferences in the 1950s and the 1960s. As a result of this reflection, articles 48 to 58 of the Additional Protocol I of 1977 reaffirm the principle of distinction between combatants and the civilian population, military objectives and civilian objects. These articles prohibit indiscriminate attacks and reprisals against the civilian population.

In December 2016, through the resolution 71/258, the United Nations General Assembly decided to organize a Conference “to find a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination”. The Conference took place in June and July 2017 and opened onto a Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons. In December 2019, 34 countries had ratified this treaty. It will come into force once 50 states have signed and ratified it.

On the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the ICRC notes that the survivors and their families are still suffering from the effects of the two bombs dropped in August 1945.

“Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 70 years later, the survivors and their families are still suffering”

The ICRC’s mobilization to ban the use of nuclear weapons is still very much ongoing. In 2019, in collaboration with a German company “Kurzgesagt – In a nutshell”, the ICRC produced an awareness video. This is part of a communication campaign launched in 2019:

“Let’s decide the future of nuclear weapons before they decide ours”

For more information on Junod’s mission in Japan

Archives

- ACICR BG 003-51 : Japan archives 1945-1946

- Fritz Bilfinger, ICRC reports on the effects of the atomic bomb at Hiroshima, in International review of the Red Cross, Vol. 97, no. 899, Autumn 2015, p. 859-882 : fac-sim.

Filmed archives

- La catastrophe humanitaire d’une bombe nucléaire (© CICR /08.2015/V-F-CR-F-01448)

Sound archives

- Interview du Dr. Junod : la situation au Japon pendant et après la Seconde guerre mondiale (© Radio suisse romande/1946/V-S-50410-A-03)

- Conséquences des essais atomiques (© Radio suisse romande/1946/V-S-50410-A-04)

- À Hiroshima sur les traces de Marcel Junod (© Radio suisse romande/V-S-50410-A-02)

Primary sources

- Marcel Junod, «The Hiroshima disaster», in International review of the Red Cross, No. 230-231, November-December 1982, p. 265-280, p. 329-344

Reference works

- Commune de Jussy ; Benoît Junod, Masaru Matsunaga ; préf. d’André Durand, Témoin d’Hiroshima : l’odyssée d’un délégué du CICR : Dr Marcel Junod 1904-1961, Jussy : Commune de Jussy, mai 2004

- Soixante ans après : le désastre de Hiroshima de Marcel Junod, sous la dir. d’Erica Deuber Ziegler, Genève : Labor et Fides, 2005

Articles and chapters

- François Bugnion, Témoin de l’indicible : le Dr Marcel Junod à Hiroshima, Colloque “Katyn et la Suisse” (18-21 avril 2007 : Genève)

- Erika Deuber Ziegeler et Jean-Louis Feuz, « Marcel Junod, la guerre atomique et le CICR », in : Les images en guerre (1914-1945) : de la Suisse à L’Europe, Lausanne : Antipodes, 2008

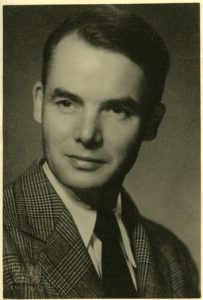

Return to Europe and writing of Warrior without weapons

In Summer 1946, Marcel Junod left the ICRC and decided to catch up on his surgical training. From September 1946 to July 1947, he worked as an intern in Paris at the Hospital Laënnec. At the same period, he wrote Warrior Without Weapons. His book is published in French in 1947, before being translated to German.

In Summer 1946, Marcel Junod left the ICRC and decided to catch up on his surgical training. From September 1946 to July 1947, he worked as an intern in Paris at the Hospital Laënnec. At the same period, he wrote Warrior Without Weapons. His book is published in French in 1947, before being translated to German.

Find the different translations of Warrior without weapons in the ICRC library’s catalogue.

He continues his studies in thoracic surgery in New York, where he meets Maurice Pate, first executive director of the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. He convinces Junod to go to China as Head of mission for the UNICEF. This mission is very difficult to carry out, and Marcel Junod’s health condition worsens. In 1949, Junod goes back to New York, but his condition worsens to the point that he has to return to Europe. He has a first surgery in London. He understands that he will no longer be able to stand up during long surgeries: he decides to continue his studies to become an anaesthetist. In 1953, Marcel Junod creates an anesthesia department at the cantonal hospital of Geneva.

On October 23rd 1952, the ICRC unanimously invites Marcel Junod to become a member of the Committee. Six years later he is appointed Vice President. In 1957, following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, he goes on a mission to Vienna and Budapest. In 1959, as he is Vice President of the ICRC, he goes to Japan and Korea.[38] The ICRC tries to find a solution to the problem caused by the repatriation of 600 000 Koreans living in Japan. This mission is difficult as the public opinion in both Japan and Korea is opposed to foreign intervention.

In 1960, Marcel Junod goes to the USSR with the ICRC President to meet Red Cross and Red Crescent National Societies. On the same year he returns to Far East and North America in order to meet National Societies.

Marcel Junod passed away in 1961 after helping awaken a patient in a coma. His funeral took place in Saint-Pierre cathedral in Geneva. Dr. René Meylan, president of the Medical Society of Geneva and Leopold Boissier, the ICRC president give two eulogies in his memory.

Warrior without weapons: a “bedside book” for every delegate?

Marcel Junod’s writings describe the delegate’s experience with great strength and great conviction. In post war Europe, Warrior without weapons is widely diffused and helps to spread the humanitarian ideas. The book receives very positive feedback after its publication. Lucie Odier notes that it is “an excellent indirect advertising for the ICRC”.

It is nevertheless important to underline that Warrior without weapons has also been criticized. The book is very partial and skips many facts. It has even been argued that it tends to be hagiographic. For example, there is not a single mention of his failure in negotiating with the Soviets in Ankara. Warrior without weapons has been written after the events and has contributed to give rise to a myth of the Dr. Junod which has never really been called into question since. His testimony and the enormous quantity of related documents tend to introduce a bias in all the portraits and works done on Marcel Junod. Thus, his writings vehiculated many imprecisions and ambiguities: the very widespread idea that Marcel Junod is the doctor that “discovered” Hiroshima is a misstatement. Reading Junod’s testimony should not lead us to forget his failings, and the disagreements he had with the ICRC and some of his collaborators.

This book is so often quoted because it is one of the very few testimonies describing the work of delegates available. It describes many of the challenges that delegates still face today in the field.

The work of ICRC delegates has indeed evolved and some of the scenes described in Warrior without weapons now seem unconceivable: no more delegates carrying a Winchester today! Nevertheless, many issues remain actual: the difficulties encountered during the negotiations, the need to establish a trust relationship with the beneficiaries on the ground, the attempts to exploit the ICRC’s investigations… all these situations still exist and are found in the contexts ICRC delegates face. Currently every staff member must sign a pledge of discretion, which forms part of their contract. Thus, all ICRC delegates “must refrain from producing or publishing in their private capacity writings […] concerning professional aspects of their work or circumstances related thereto”. Delegates are required to observe the utmost discretion in matters of service. This duty of discretion and confidentiality continues even after the departure of the collaborator. The publication of testimonies by ICRC delegates therefore remains open to question: any writings covering a period for which the archives are still classified may be problematic. Is there a risk that information will be released that could hinder the ICRC’s work on the ground or damage its image?

More generally, ICRC collaborators are not supposed to express themselves on the ICRC activities without the agreement of their hierarchy.[39] These elements explain why Junod’s testimony is rare: this text is unique considering what it shows of a delegate’s work. In 2005, François Bugnion, former director of international humanitarian law at the ICRC sums up Junod’s importance:

“Junod, by his action, created an operational model of delegate. In this sense, all of our delegates are the spiritual heirs of Marcel Junod.”[40]

Publications and films based on Warrior without weapons :

Book :

- Jean-François Berger, Marcel Junod : 1904-1961, Genève : Société Henry Dunant ; Georg, 2019

Audiovisual documents :

Find two films produced by our colleagues in Paris in 2013 ICRC audiovisual archives :

- Marcel Junod, le troisième combattant : première partie (1935-1939) (© CICR, 06.2013, V-F-CR-F-01472-1)

- Marcel Junod, le troisième combattant : deuxième partie (1939-1945) (© CICR, 07.2013, V-F-CR-F-01472-2)

- In 2013, the Japanese production company Junod Animation Production Committee LPP produced an animation film Dr Marcel Junod : putting humanity first (© Junod Animation Production Committee LPP, 05.2013)

- Docteur Junod, Le Troisième Combattant, film produced by Romain Guélat from a screenplay by Jean-François Berger (©Image et Son SA, 2018)

[1] TROYON Brigitte and PALMIERI Daniel, « The ICRC delegate: an exceptional humanitarian player ? », International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 89, no 865, mars 2007, p. 100

[2] DE TSCHARNER Bénédict, Inter Gentes : Hommes d’État, diplomates, penseurs politiques, Édition de Penthes, Genève, 2012

[3] Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, no. 398 , octobre 1935, p. 777

[4] Circulars 319 and 320

[5] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 35

[6] BAUDENDISTEL Rainer, Between bombs and good intentions: the Red Cross and the Italo-Ethiopian war 1935-1936, Berghahn books, New York, 2006, p. 127

[7] Circular 323, Annex II

[8] Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 27 July 1929.

[9] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 61

[10] BAUDENDISTEL Rainer, Between bombs and good intentions: the Red Cross and the Italo-Ethiopian war 1935-1936, Berghahn books, New York, 2006, p. 274

[11] Circular 325

[12] Conférence Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Dixième conférence internationale de la Croix-Rouge, tenue à genève du 30 mars au 7 avril 1921 : compte-rendu, Genève : Imprimerie Albert Renaud, 1921, p. 218

[13] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 98

[14] Circular 330

[15] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 103

[16] MARQUÉS Pierre, La Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre d’Espagne (1936-1939) : les missionnaires de l’humanitaire, Paris ; Montréal : L’Harmattan, 2000, p. 379

[17] DJUROVIC Gradimi , The Central tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross, 1981, p. 104

[18] COURVOISIER Raymond, Ceux qui ne devaient pas mourir : de la Guerre d’Espagne aux réfugiés palestiniens, quarante ans de combat sans armes, Editions Robert Laffont, Paris, 1978, p. 18

[19] Comité international de la Croix-Rouge, « Marcel Junod : membre du Comité International de la Croix-Rouge », Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 43, no 511, 1961, p. 336

[20] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 140-141

[21] Comité international de la Croix-Rouge, « Mission en Allemagne », Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 21, no 250, octobre 1939, p. 789

[22] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 143

[23] Probably the Danziger Neueste Nachrichten

[24] Comité international de la Croix-Rouge, « Visites de camps, par des délégués du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge, en pays belligérants et en pays ayant rompu les relations diplomatiques avec certains Etats. », Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 21, no 252, décembre 1939, p. 961

[25] Comité international de la Croix-Rouge, « Chronique de l’Agence centrale des prisonniers de guerre », Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 22, no 259, juillet 1940, p. 548

[26] Comité international de la Croix-Rouge, « Missions de Comité international de la Croix-Rouge : visite de camps de prisonniers de guerre et d’internés civils en France », Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 22, no 260, août 1940, p. 605

[27] Comité international de la Croix-Rouge, « Mission à Vichy et mission à Berlin », Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 22, no 260, juillet 1940, p. 673

[28] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 204

[29] Daniel Palmieri and Fania Khan Mohammad, « Des morts et des nus : le regard du CICR sur la malnutrition extrême en temps de guerre (1940-1950) », in Renée Dickason, Mémoires croisées autour des deux guerres mondiales, Paris : Mare & Martin, 2012, p. 88

[30] JUNOD Marcel, Warrior without weapons, London : J. Cape, 1951, p. 204

[31] Ibid., p. 229

[32] Commune de Jussy ; Benoît Junod, Masaru Matsunaga ; pref. by André Durand, Témoin d’Hiroshima : l’odyssée d’un délégué du CICR : Dr Marcel Junod 1904-1961, Jussy : Commune de Jussy, mai 2004, p. 19

[33] JUNOD Marcel, “The Hiroshima disaster“, in International Review of the Red Cross, No. 230-231, November-December 1982, p. 265-280, p. 329-344

[34] In 1954, Masao Tsuzuki submits two reports “Atomic bomb injury from medical point of view” and “Medical effects of the Bikini-ashes (a preliminary report)” in Documents and summary records [of the] Commission of experts for the legal protection of civilian populations and victims of war from the dangerous of aerial warfare and blind weapons, Geneva, from 6 to 13 April 1954

[35] Marcel Junod is refering to the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare. Geneva, 17 June 1925.

[36] JUNOD Marcel, “The Hiroshima disaster“, in International Review of the Red Cross, No. 230-231, November-December 1982, p. 344

[37] HUBER Max, « La fin des hostilités et les tâches futures de la Croix-Rouge », in Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 27, No 321, septembre 1945, p. 660

[38] ICRC, Annual report : 1959, Geneva : ICRC, 1960, p. 19

[39] ICRC, Code of conduct for employees of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva : ICRC, 2018

[40] https://www.swissinfo.ch/fre/marcel-junod–le-secouriste-suisse-d-hiroshima/4649694

Comments