The V CI sub-fonds, Iconographic Collections, contains approximately 330 images of historical interest related to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), most of which are large-format originals dated between 1845 and 1997. The sub-fonds illustrates the evolution of the ICRC’s activities, tools and relations since its creation in 1863 through a relatively small and well-defined corpus of articles and sheds light on the organization’s actions, symbolic value and areas of work over the past 150 years. These visual documents complement the written documents contained in other sub-fonds. Work has recently been carried out to consolidate and clarify the inventory, expand the description of each document, add new documents and physically repackage the entire collection using appropriate storage materials. The aim of this article is to introduce the contents of the collection and how it has been optimized.

Creation of the collection

It remains unclear how the iconographic collection first came to be constituted. It would seem that the documents were gradually assembled as they were received by the ICRC starting in the 19th century. Some of the archived images, most likely acquired by past ICRC presidents, were used for decorative purposes. (During the interwar period, some were displayed in the Villa Moynier.)[1] However, no records were found that explain the existence, provenance, use or place of conservation for most items in the V CI sub-fonds. It was only in 1986 that inventory was taken of the visual documents (including photographs and photo albums) stored in the ICRC Archives facilities. Many items were indexed in that first list, which unfortunately did not include any descriptions or context.

In 1998, work on a detailed inventory was finally begun, and part of the collection was repackaged. However, the project was never finished, and some 40 documents were left out of the inventory. It was only recently that description and processing of the sub-fonds was begun again so that the collection might be fully inventoried and repackaged in line with current archival standards.

Methodology

The first step in creating a archival description is always establishing how the collection or group of archives was originally constituted, then understanding its history and organizational structure. An in-depth understanding of the source organization allows for a better grasp of the content of a fonds. In this case, the existing history was updated.

We were quickly able to move on to step two: comparing the inventory begun in 1998 against the boxed documents. First, we verified that all the listed documents were present and checked that they matched the descriptions. We also added to the inventory any documents that had not yet been processed. The inventory check gave us an opportunity to study how the sub-fonds was organized, the state of the documents and how they had been stored. It was also a chance to seek out connections between these items and other sub-fonds held by the ICRC, as well as the collections of other Geneva heritage institutions that conserve the same types of images. In practical terms, the inventory check involved consulting each item in turn, noting down its unique reference number and checking it against the inventory list. Then, each item’s reference number, description, date, type (photograph, certificate, album, etc.), subject keywords, version (original or copy), format (A4, A3, etc.) and state of conservation were entered into an Excel spreadsheet. A final column in the spreadsheet lists complementary sources found after searching in various databases.

Based on the information gathered in step two, the third step was to form recommendations for further processing. Three major improvements were proposed and accepted. The first was to modify the way the documents were ordered, as they had originally been filed based on a simple sequential list, which made the collection difficult to navigate. Given that the fonds had been artificially constituted to begin with – that is, not organized based on any particular system – modifying the order did not pose any problems, so long as the original numbering was conserved for reference. The second modification was to standardize the descriptive notes, expand the titles and content descriptions, and add complementary sources and references to copies conserved in other Geneva institutions. In a similar vein, it was also necessary to plan updates to descriptions of the context, content and order of the fonds. The third modification involved replacing unsuitable packaging materials with boxes and folders of the proper size.

The fourth step was to put the first two recommendations into practice: first, by changing the order of the inventory while adding missing information to the notes. This resulted in a clearer overall picture of the collection, which made it possible to update descriptions of the context, content and order.

The fifth and final step was to implement the third recommendation: that is, physically re-order the collection and assign each document a reference number based on the new organizational system. It was also at this stage that we upgraded the storage system and materials. Wherever possible, we replaced metal paperclips and support devices with alternatives made of acid-free plastic or paper. Some photographs also needed to be reattached to the albums in which they were stored. All documents were also transferred to new acid-free folders and boxes of appropriate size. Once the collection was repackaged, it was moved to a suitable storage space and the contents of each box were labelled.

Content and organization of the collection

The iconographic collection is made up of visual documents, most of which are large format (A4 to A1, approximately). It comprises photographs, photo albums, lithographs, engravings, photo-engravings, posters, drawings, certificates of special honours or appreciation, prizes, thank-you letters and drawings, art publications, maps, press cuttings, postal stamps and postcards.

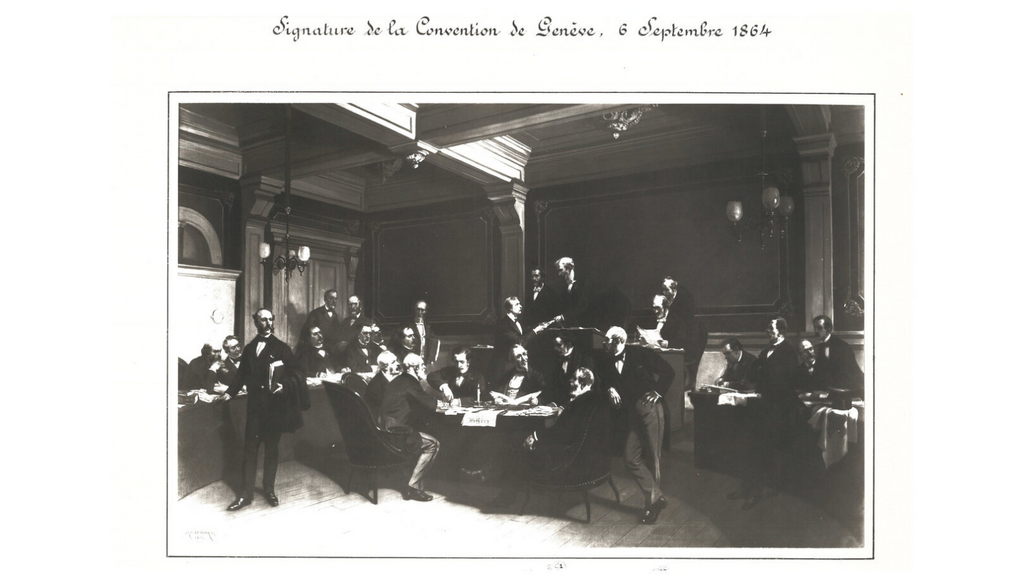

The collection is divided into ten series. The first three comprise photographs and lithographs related to members of the Committee, signatures of the Geneva Conventions (of 1864, 1906, 1929 and 1949), and the International Conferences of the Red Cross. The fourth series contains photo albums, letters and drawings presented in thanks to the ICRC for its work in the field. Another series contains certificates awarded to the ICRC and its presidents by public and private organizations. There is also a collection of lithographs, photo albums, certificates and photographs of medals, all of which illustrate relations between the ICRC and the National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and their members. Then there is a collection of artworks (lithographs, engravings, drawings, paintings, postcards and art publications) related to the ICRC and its work. Another complementary series depicts how the medical supplies used by the ICRC changed over the years. The final series contains 19th-century photographs of Geneva, where the ICRC has its headquarters.

Selected items of interest

It is extremely important to establish a detailed and exact description of each document to make it easier to find pertinent information and identify sources. Thanks to some in-depth research, we were able to rediscover certain documents and highlight their true value.

Triptych of drawings[2] by Kobayashi Kiyochika of a visit by Empress Shōken to a military hospital in Hiroshima during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)[3]

This triptych, dated 1895, shows Empress Shōken[4] at a military hospital in Hiroshima during the war with China. The Empress came to Hiroshima in March 1895 to join her husband, who had moved his military headquarters there from Tokyo to be in closer communication with his troops. During her stay in the city, the Empress visited hospitals where wounded soldiers were receiving care.

This triptych, dated 1895, shows Empress Shōken[4] at a military hospital in Hiroshima during the war with China. The Empress came to Hiroshima in March 1895 to join her husband, who had moved his military headquarters there from Tokyo to be in closer communication with his troops. During her stay in the city, the Empress visited hospitals where wounded soldiers were receiving care.

The drawings are by Meiji-era Japanese artist Kobayashi Kiyochika (born 10 September 1847 in Honjo, died 28 November 1915 in Tokyo-fu). Kiyochika practiced ukiyo-e style and is best known for his drawings of scenes that reflect the Tokyo area’s transformation as Japan modernized, as well as for his woodcuts, mostly produced between 1876 and 1881. However, he also produced illustrations and sketches for newspapers, magazines and books, and he created a number of prints illustrating scenes from the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905).

The ICRC did not carry out any humanitarian activities in the First Sino-Japanese War. It is therefore unknown how these drawings came to be in the organization’s possession. They may have been presented as a gift during an official meeting between a member of the Committee and a representative of the Japanese Red Cross Society sometime between 1895 and 1912, when the Empress Shōken Fund was created.[5]

Photo album[6] of Ras-el-Tin internment camp in Alexandria, Egypt (First World War)

These photographs of Ras-el-Tin camp were likely taken in late 1916.

These photographs of Ras-el-Tin camp were likely taken in late 1916.

On 5 January 1917, ICRC delegates visited this British military-run internment camp as part of their “travels in France, Corsica, Egypt and the Indies”.[7] The delegates set out in November 1916 with the aim of visiting Ottoman prisoners of war being held in those countries. Ras-el-Tin, located five kilometers outside Alexandria, was home to 69 Ottoman civilians and 400 interned Austrians and Germans who happened to be in Egypt when war was declared and were unable to return to their homelands.

The images were captured by Austrian photographer Theodor Kofler (born 27 July 1877 in Innsbruck, died October 1957 in Bukoba). Kofler moved to Egypt in the early 1900s and went into business with two other photographers before purchasing the Cairo Studio in 1908. In 1914, he took the first known photographs of the pyramids of Giza from an airplane. On 2 August of the same year, Great Britain declared war on Austria, and the British colonial government deported all Austrians subject to conscription to either the Alexandria region or Malta. Kofler was sent to Malta, where he photographed prisoners until he was freed and sent back to Egypt in April 1916.

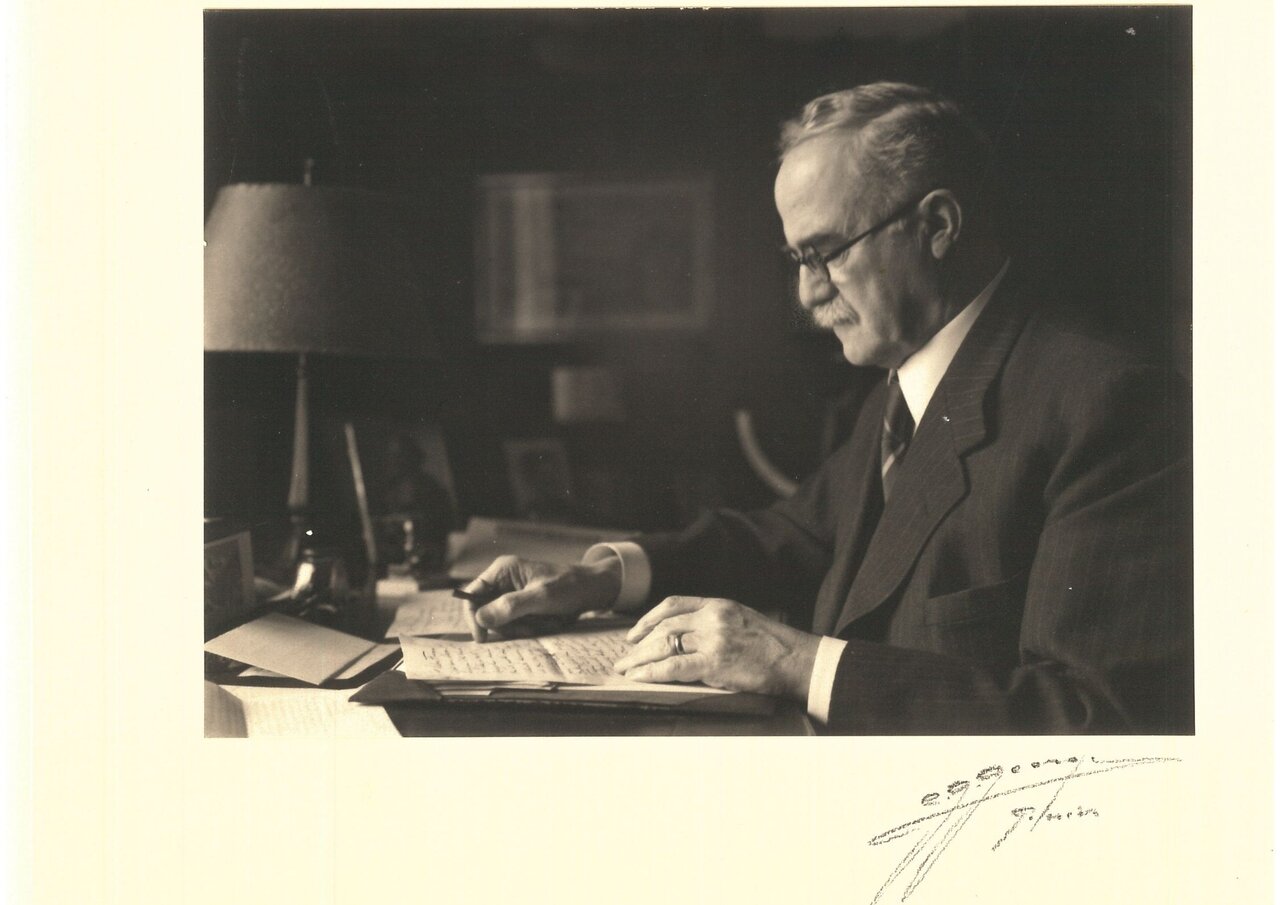

Photographic print on cardboard[8] of Max Huber at his desk, likely in 1944

Max Huber (born 28 December 1874 in Zurich, died 1 January 1960 in Zurich) studied law and earned a doctorate from the University of Berlin before being named Professor of Constitutional, Ecclesiastic and International Public Law at the University of Zurich. He later became a legal adviser to the Swiss Federal Council, where he played a major role in establishing Switzerland’s neutral stance during the country’s entry into the League of Nations in 1920. He was a member the Permanent Court of International Justice in the Hague from 1922 to 1932 and led the Court from 1925 to 1927. He was a member of the Committee and succeeded Gustave Ador as President of the ICRC from 1928 to 1944, during which time he took on a decisive role in its organization (overseeing, for example, the adoption of the first Statutes of the International Red Cross in 1928) and contributed to the development of international humanitarian law.

This image was captured by Charles-Gustave Georges (born January 1887 in Geneva, died 23 September 1965 in Geneva), a well-known portraitist who practiced art photography for over 50 years.

Photo album[9] of action by the Eritrean Liberation Front (December 1970)

A faction of the Eritrean Liberation Front

The Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) was the primary movement for Eritrean independence from Ethiopia in the 1960s and 1970s. It was founded in Cairo in July 1960 by Idris Muhammad Adam and other Eritrean intellectuals and students. The ELF fought in the war of independence from 1961 to 1991.

This album was a gift from Saleh Ahmed Ayai, a representative of the ELF general staff, to Jean-Pierre Maunoir, an ICRC delegate, at a meeting in Damascus in February 1971, where the situation in Eritrea was a central topic of discussion. The photographs show the ELF in combat. They were taken by Ahmad Abu Saada, a Syrian photographer and television producer who was sent on assignment to Eritrea in late 1970 by the Syrian Ministry of Information.[10] He worked as an embedded reporter with the ELF for several weeks.

Revolutionaries share a meal with a farm boy

[1] The Villa Moynier served as the ICRC’s headquarters from 1933 to 1946.

[2] A CICR V CI 08-022.

[3] The First Sino-Japanese War (1 August 1894–17 April 1895) was fought between China and the Japanese Empire, originally over control of Korea, at the time a tributary State of China. There was intense fighting, including naval warfare. After a series of military defeats, China’s Qing-dynasty leaders were forced to sign the Treaty of Shimonoseki and pay reparations in exchange for Japan’s withdrawal from the Korean peninsula. China also had to cede the island of Formosa (Taiwan), the Penghu (Pescadores) Islands and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan.

[4] Empress Shōken (born 9 May 1849 in Kyoto, died 9 April 1914 in Numazu) was the wife and consort of Emperor Meiji (born 3 December 1852 in Kyoto), who ruled as Japan’s 122nd emperor from 3 February 1867 until his death on 30 July 1912. His 45-year reign was a time of profound change for the country, when the Japanese Empire entered modernity and consolidated its dominant position in East Asia.

[5] The Fund was established at the 9th International Conference of the Red Cross in Washington, D.C. at the initiative of the Empress herself, to promote “relief work in times of peace” with an endowment of 100,000 yen in gold. The initial endowment was supplemented several times over the years by donations from the Japanese imperial family, government, Red Cross Society and public.

[6] A CICR V CI 04 01-001.

[7] Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No. 191, July 1917, pp. 254–256.

[8] A CICR V CI 01 06-004.

[9] A CICR V CI 04 01-004.

[10] A CICR B AG 200 072-002.

Comments