In 1921, Greece and the Ottoman Empire were at war. Two years later, at Lausanne, Greece and the newly formed Republic of Türkiye would sign a peace treaty and find a lasting solution to the conflict with a population exchange involving roughly a million and a half people. But in May 1921 the war was ongoing, so the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) sent one of its delegates on a protection mission on behalf of refugees in Anatolia. In the ICRC Archives are photographs from the conflict, now too often forgotten, which document the violence that was unleashed and the upheaval suffered by those caught in the middle.

A million and a half – that is the estimated number of refugees exchanged by Greece and Türkiye in 1923.[1] Over the course of centuries, the region stretching from Greece to the Caucasus had been home to some of the world’s great civilizations. From the ancient Athenians to the Ottomans, the constant movement of people created an ethnically and religiously diverse populace that comprised, among others, Greek Orthodox Christians, Armenian Orthodox Christians, Syriac Christians and Muslims.[2]

After the First World War, the Ottoman Empire was dismantled and occupied by the Greek military and the Allied powers. In 1919, Turkish nationalists, who refused to accept the occupation, took up arms. A war of independence broke out. In 1922, faced with a large-scale conflict and a flood of refugees to Greece, the High Commissioner for Refugees, which had been recently created by the League of Nations, took charge. The agency proposed what it considered a viable solution to the conflict – a population exchange between the two countries.[3]

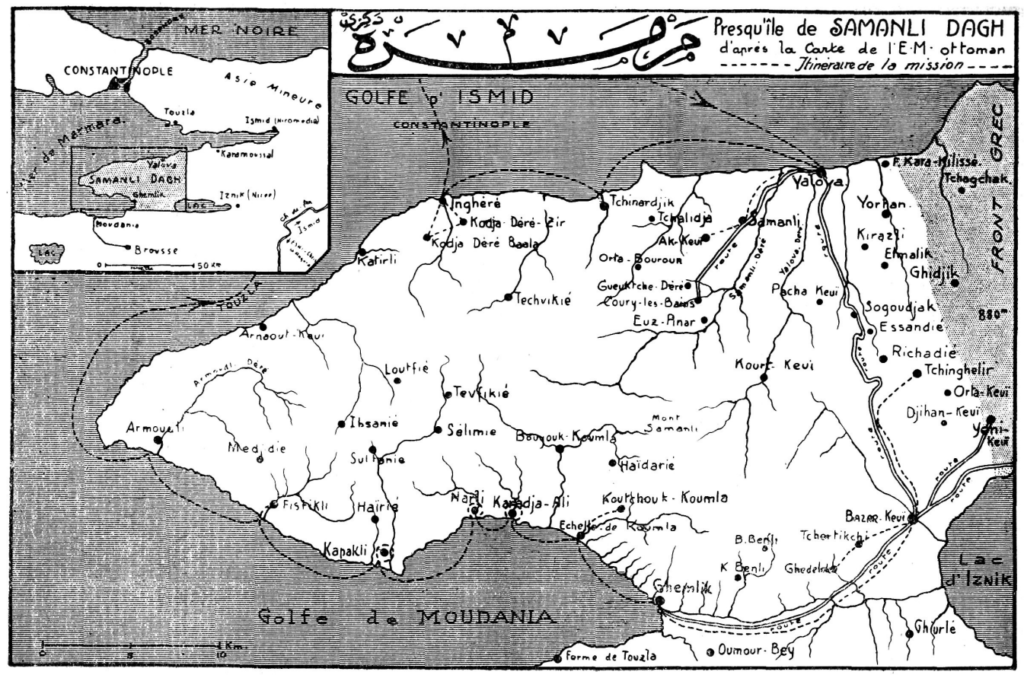

At the request of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society, the ICRC sent delegate Maurice Gehri to Asia Minor from 12 to 26 May 1921. Gehri was part of an Inter-Allied mission tasked with investigating the atrocities that had taken place around the Samanli-Dagh peninsula (now the Armutlu peninsula [*]), not far from Constantinople.

During the Greco-Turkish War, the ICRC worked in circumstances that can only be understood by looking at many decades of history: in the region, caught in the vice grip of various forms of nationalism, many had been persecuted for their religious beliefs and had borne the brunt of policies aimed at ethnic homogenization.

The mission was unique for several reasons – its brevity, the nature of its inquiries, the unforeseen circumstances it would face – but most especial was the diary that Gehri kept, which gives precious information on the events. And the ICRC’s photographic archives contain snapshots taken by the delegate himself during his time in the area. Now, 100 years after the end of the war, these and other archival sources shed an illuminating light on the Gehri mission.

Origins of the Greco-Turkish War

The Ottoman Empire conquered vast territories, from North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula to South-Eastern Europe, encompassing many communities of varied ethnicity as well as religion. Native speakers of Greek had been present in Greece and Anatolia for three millennia, from the coast of the Aegean all the way to the edge of the Black Sea. The peaceful cohabitation of the Empire’s various peoples had for many years relied on the so-called millet system, which granted a degree of autonomy to non-Muslim minorities, often in exchange for payment of a special tax. The three major categories of minorities were Jews, Orthodox Christians – including the Greeks – and Armenians.[4]

However, the millet system was unable to cope with separatist stirrings in the Balkans, and the Ottoman Empire lost its territories in Europe over the course of the 19th century: Greece became independent in 1831, followed by Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and Montenegro in 1878 after the Russo-Turkish War. During that war, the president of the ICRC, Gustave Moynier, urged Ottoman officials to form a society to help the wounded. The Ottomans asked that the emblem of the red cross be replaced by a crescent, which better represented the Muslim aid workers. Thus the Ottoman Red Crescent Society was founded in 1877.[5]

While the crumbling Ottoman Empire was considered the “sick man of Europe”, European powers were pondering the future of the East and eyeing its territories.[6] The Europeans strategically lent support to Christian religious minorities and their separatist causes to interfere in the internal affairs of the Ottoman Empire and thus weaken it.[7] For example, France, which was already involved in the capitulations system of the 16th century,[8] declared itself the protector of the Maronite Christians of Mount Lebanon and Syria. Russia proclaimed itself the protector of the Orthodox Christians and Armenians; Austria and Italy strengthened ties with Christians linked to the Catholic Church; and the British maintained relations with the Copts in Egypt and the Assyrians in Iraq.

Faced with territorial losses, Ottoman rulers came to the conclusion that the close relationship between the Empire’s Christians and the European powers was the primary cause. As they jockeyed among themselves for power, European nations had interfered in the Empire’s affairs on multiple occasions. This meddling was a factor in the decision to “cleanse” the Ottoman Empire’s population.

From the latter half of the 19th century, an about-face of identity took place in the multiethnic, multireligious empire in which the millet system had prevailed for decades. The result was radicalization, first Pan-Islamic,[9] under Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and then Pan-Turk,[10] under the aegis of the nationalist Young Turk movement. The Ottoman Empire settled on a policy of ethnic homogenization: by ridding itself of the minorities supported by the Europeans, it could put an end to the internal tensions.[11]

The feeling of hatred towards the Ottoman Empire’s Christians resulted in numerous massacres. In the 1890s, the Ottoman Armenians were the targets of persecution in the Hamidian massacres,[12] followed in 1909 by all of the Christians in and around Adana.[13] The loss of Libya in 1911 during the Italo-Turkish War and the loss of European territories during the Balkan wars of 1912 to 1913 traumatized the Ottoman Empire. There began to be talk among the Ottoman army’s leadership of ethnic cleansing against the Christian communities of Anatolia, which was propelled by a sense of vengeance that had been exacerbated by the Young Turk movement.[14] Ottoman leaders seized the opportunity of the First World War and, in 1915, began to deport or eliminate Christian communities that no longer fit into the image of Turkish national unity. Armenians paid the heaviest price, followed by Orthodox Greeks and Assyrians.[15]

In 1918, after four years of war, the Ottoman Empire capitulated to the Allied Powers and signed the Armistice of Mudros. During the Paris Peace Conference, the Allies imposed the very severe Treaty of Sèvres on the Ottomans and divvied up the Empire’s territories among themselves.[16] The straits were occupied and demilitarized, and the territories in the Middle East were divided according to the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement, which had been concluded between France and the United Kingdom in 1916. In May 1919, Greece began its military occupation of Smyrna and part of the Aegean coast of Anatolia. The Greek government, particularly Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, had expansionist designs on Anatolia and seemed to be on the brink of realizing its irredentist-nationalist ambition, the Megáli Idéa.[17] The Greek military occupation turned Muslim public opinion against the Allies and fuelled a nationalist resistance centred around Mustafa Kemal, later known as Atatürk, who rejected the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres.[18] The Greco-Turkish War broke out in 1919, and Kemal pursued the policy of ethnic homogenization begun by his predecessors.[19] In the opposing camp, the Greek forces in occupied territory also massacred Muslims.

It was against this backdrop that the Ottoman Red Crescent Society called on the ICRC for help. The ICRC tasked delegate Maurice Gehri with joining an Inter-Allied mission to investigate the facts on the ground and bring relief to Muslim communities.[20]

The Gehri mission of May 1921: Bearing witness to a violent occupation

Like much of Anatolia, before the war the peninsula of Samanli-Dagh was largely Muslim, with a sizeable number of Christian minorities, including Greek Orthodox and Armenian Christians. In 1919, during the Greek occupation, the Greek armed forces took control of the peninsula, with the intent of permanently annexing the territory. The occupation was difficult, as the Greek army lacked the necessary manpower and funds to control the peninsula completely. It relied instead on paramilitary groups made up of Greek Orthodox and Armenian civilians who had survived the deportations and massacres perpetrated by the Ottoman armed forces during the First World War. In an already tense climate in which the various religious groups eyed each other with hostility, the actions of the paramilitary groups set off a chain reaction of abuses and vendettas between Greek and Muslim civilians.[21]

In 1920, news coverage of the conflict primarily focused on what was happening to the Christians of Asia Minor, linking their suffering to that of the Armenians, at the expense of Muslim victims. However, Arnold J. Toynbee, an English journalist with the Manchester Guardian who would later become a celebrated historian, was reporting on the fate of Muslims caught up in the conflict. Toynbee drew public attention to a number of massacres and other acts of violence committed against Muslims; he also highlighted cases of villages on the peninsula being burned down with impunity owing to the Greek forces’ laxity in maintaining public order.[22] In April 1921, the Ottoman Red Crescent Society alerted the ICRC to the fact that the Greek army was deporting and massacring Muslims on the peninsula with the aim of “extermination”.[23] Muslim citizens were furthermore not being allowed to leave and take refuge elsewhere.

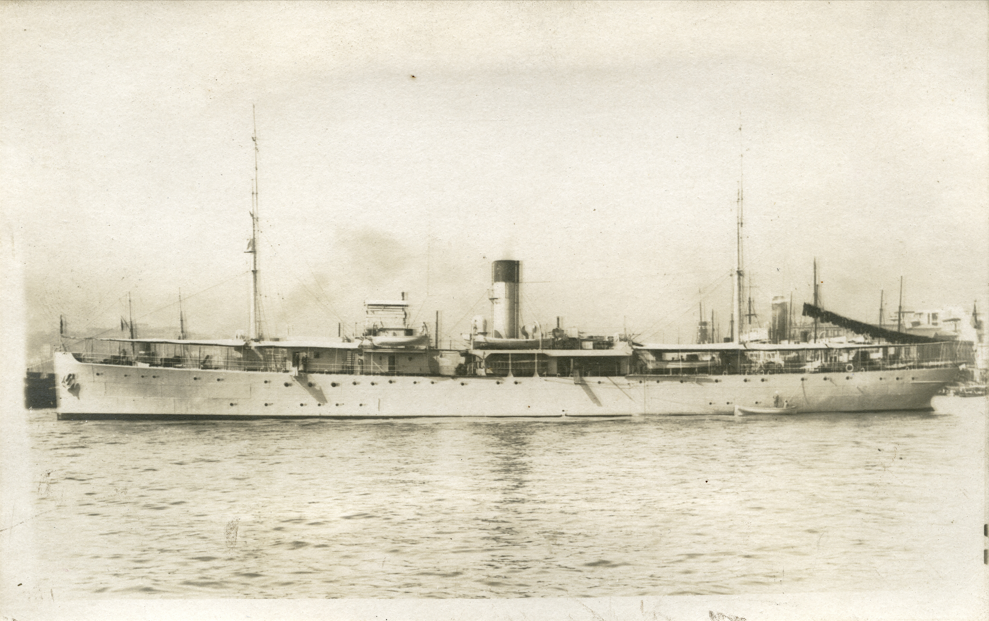

Alerted to these facts, the Allied authorities based in Istanbul, in particular the British high commissioner, Sir Horace Rumbold, decided to dispatch a fact-finding mission. The ICRC was invited to join the mission, otherwise made up of members of the Allied powers, because the Ottoman government found the organization trustworthy. The ICRC tasked delegate Maurice Gehri, a Swiss citizen, with meeting with the persecuted communities. Over ten days, the group sailed on the HMS Bryony from village to village around the Samanli-Dagh peninsula, as documented in the important diary that Gehri kept throughout the mission.[24]

Samanli-Dagh peninsula, mission itinerary. (Maurice Gehri in International Review of the Red Cross, “Mission d’Enquête en Anatolie, 12–22 Mai 1921”, Vol. 3, No. 31, July 1921, pp. 721–735.)

© ICRC Archives (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War: The English torpedo boat HMS Bryony, which the fact-finding mission used for its voyage in Anatolia. V-P-HIST-E-07061

© Turkish Red Crescent / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, maritime route from Constantinople to Yalova: Members of the mission on the Gul Nihal. From left to right: Lieutenant Holland (United Kingdom), Captain Lucas (France), Lieutenant Bonaccorsi (Italy) and Maurice Gehri, representing the ICRC. V-P-HIST-E-07087

From the moment he set foot on the Bryony on 12 May 1921, Gehri was side-lined; in his diary, he confessed to feeling like an intruder. Indeed, General Franks, a representative of the British army, expressed surprise when he learned that the delegate was joining the mission, and neither the captain of the ship nor the crew were aware that Gehri was coming. Gehri did not have a cabin of his own and had to sleep on deck. He was not asked to dine with the mission’s officers, nor was he invited to their daily briefing; he only received a few scraps of information from Franks. Nevertheless, Gehri would not be defeated and, aware of the importance of the mission, adapted quickly to the difficulties.

© Turkish Red Crescent / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: View of Ghemlik from the sea. V-P-HIST-E-07062

In the afternoon of 12 May, the ship weighed anchor off the coast of Ghemlik. The fact-finding mission began to visit villages the following day, but Gehri was blocked from joining by General Franks, who said that Gehri was not an official member of the mission and therefore could not come with. Disappointed, Gehri decided to carry out his own investigation, beginning in the city of Ghemlik. Throughout his trip, he was accompanied by local interpreters who spoke Greek and Turkish. When he made it ashore, Gehri was quickly approached by local Greek and Armenian notables. They told him about forced conversions to Islam and massacres that had occurred the previous year – in Iznik (the ancient Greek city of Nicaea) and Lefke in particular, where 2,000 people had died. Greek Orthodox Christians, Armenians and Jews had been slaughtered by Muslims after the mufti of Mudanya had directed it. According to the local notables, the Greek occupiers were there simply to retake what belonged to the Greek people, in a region where they were the majority and, to their minds, the “active, rich and business-minded” part of society.[25]

One of them even confided that the Greeks “brought civilization here, chasing into the interior of Asia this damnable race who have not made progress in centuries and are incapable of doing so, and who should be dragged out of Europe and off the Asian coastline for the good of civilization”, a vivid illustration of the communal tensions the delegate was confronted with.

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: The Ghemlik mosque, which housed the largest group of Turkish refugees. V-P-HIST-E-07066

The same morning, Gehri attempted to speak with the Muslim refugees confined in the Ghemlik mosque, the only place to house them. He quickly realized that the Greek army’s presence would impede any conversation. In the afternoon, when the soldiers were gone, tongues loosened, and the refugees told Gehri that the Greek occupation forces had chased them out of their village, Bazar Keuï, which the mission had gone to visit just a few hours earlier. They said they had had only an hour to prepare, after which the village was set aflame and their houses burned down. While they were on the road looking for somewhere to take shelter, members of the Greek military as well as Greek and Armenian women had robbed them of everything they had. Unlike Greek and Armenian refugees, who received food from the Greek army, the Turkish refugees were not given anything to eat and were fed by those Muslim inhabitants of the surrounding villages who still had some food left. Their living conditions were deplorable, and some had already died of starvation. Gehri understood that if nothing was done all the remaining refugees would also starve to death.

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War: Three of the five Turks aboard the Bryony. Photo taken upon returning to the ship, after a violent encounter in which Greek women in Ghemlik almost tore a police lieutenant to pieces. The officer’s face betrays his fatigue and post-traumatic state after a chaotic altercation with the crowd. V-P-HIST-E-07068

The Allied mission, back from a day of investigating, arrived at Ghemlik by car. Before they had even left the vehicle, a crowd of Greek women descended on one of the Turkish police lieutenants accompanying the mission in order to tear him to pieces. His hat and epaulettes were ripped off, but the other members of the mission managed to get him on board the Bryony. Shortly before the incident, a Greek refugee from the neighbouring village of Foulardjik had explained to Gehri that the officer had tortured and killed the village priest, explaining the ensuing chaos.

The following day, Gehri continued to visit Ghemlik and meet with residents. Chukri Bey, an Albanian who had lived there for some twenty years, told the delegate that the Greeks were pillaging and burning down Muslim villages with complete impunity, in full view of the Greek military.

After this encounter. Gehri was approached by Greeks, who told him about a funeral service in a nearby Greek Orthodox church and asked him to attend. Gehri went, capturing the moment in a photograph (see below). Two young Greeks from Ghemlik had been killed in the village of Koumla-Iskele three days prior, when the Bryony had arrived. The bodies were mutilated, and it was clear that a terrible crime had taken place. After the ceremony, Gehri spoke with Monsignor Vassilios, the archbishop of Nicaea. He told Gehri about the massacre perpetrated by Turks the previous year at Nicaea, which Gehri here refers to in his diary using the Greek name. According to the archbishop, “The Greek army has been far too gentle in cracking down. I’m a clergyman, not a soldier, but I would’ve wanted to exterminate all the Turks and not leave a single one behind.”

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Ghemlik, orthodox church: Funeral rites for two young Greeks from Ghemlik killed at Koumla-Iskele on 12 May. Seated at right, Monsignor Vassilios, archbishop of Nicaea. V-P-HIST-E-07069

The following day, Gehri returned to the Ghemlik docks to meet the families of the two young men. They told him that the youths had left to visit a friend in the neighbouring village and had been found dead on the beach. Another person added that, when it had happened, the young men had been wearing fezzes and could have been mistaken for Turks. The delegate wondered whom to believe.

On the morning of 15 May, three villages were ablaze. The smoke could be seen from Ghemlik, which Gehri photographed. The mission, which was set to disembark at Karadja-Ali, could not do so because of the heat.

At left: © ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Fire in the village of Karadja-Ali, Sunday, 15 May. V-P-HIST-E-07072

At right: © ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Fire in the village of Narli, Sunday, 15 May. V-P-HIST-E-07073

The mission decided to visit the Muslim village of Koutchouk-Koumla. Upon their arrival, they found around 1,000 refugees waiting for them, imploring them to take them somewhere safe. Their houses had been pillaged and burned, and some of their loved ones had been raped or killed. The terrified refugees wanted the mission’s protection and decided to follow them. They settled on the beach near the wharf and spent the night sitting around fires they had lit. The Bryony, anchored offshore, lit up the beach and the surrounding hills with its searchlights to reassure the refugees.

On Monday, 16 May, General Franks finally received word from his superior and authorized Gehri to accompany the mission to the village of Kapakli. When they arrived, the village was still smouldering from the fire the night before, and the villagers had fled to the mountains. According to survivors, the Greek army had come to pillage, burn and kill. The Greek staff officer accompanying the mission contested this and, spotting a young girl, requested that they question her, as “the truth comes from the mouths of babes”. The girl declared categorically that the wrongdoers had been Greek. The few survivors asked to be evacuated to somewhere peaceful. They were told to alert the others hiding in the mountains and to meet on the beach; from there, they would be taken to Koutchouk-Koumla the following day.

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Fire in the village of Karadja-Ali, Sunday, 15 May. V-P-HIST-E-07074

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Fire in the village of Karadja-Ali, Sunday, 15 May. V-P-HIST-E-07075

Gehri wrote in his diary, “The villages burned down before our eyes, the corpses by the dozen, the terror of these people (.…) Everything points to the danger being imminent and terrible and obliges us to save the refugees right now.” Drawing on the ICRC’s good relationship with the Ottoman Red Crescent Society, Gehri sent a message asking for help evacuating the refugees to Constantinople. His mission had now entered a second phase: it was no longer about fact-finding but instead evacuating the refugees.

However, Gehri faced the “stubborn opposition” of the British high commissioner in Constantinople, who refused to accept refugees in the capital, citing concerns of overcrowding given the flood of refugees from other regions of Anatolia and the Russian civil war. He also stated that the coal crisis in England meant that boats could not come to the peninsula, which was four hours from Constantinople. It seemed to be one more excuse.

The next day, Gehri was almost caught in a gunfight. He was visiting Koumla-Iskele with Corporal Costas, a Greek non-commissioned officer in charge of an armed group of soldiers and civilians. An old woman returning from the brush approached Gehri and said that a Greek soldier had just threatened her with a bayonet. The delegate wrote in his diary:

« In the distance, we did see Greeks uniforms moving about. (…) Impossible to say how many. Only one emerged from the brush onto the road, followed by an armed civilian, whom the people on the beach recognized immediately as a bandit who usually accompanied the Costa detachment. A child was with them. At the sight of them, the people on the beach returned to their hamlet. The bandit, armed with a rifle and a dagger, was literally armoured with cartridges. The boy, 14 or 15 years old, had a revolver and a dagger. The soldier had his rifle and cartridge belt. Costas and I prepared the defence. He had his rifle, which he showed me how to handle; I had a Browning and three magazines. The entire village was there, watching what took place in great silence. After a few minutes of animated muttering, the bandit and the boy came towards the village alone. We went up to them, and I asked them questions: Where did they come from? Where were they going? While talking, the bandit entered the village with the boy, sat down on a pile of bricks, unwrapped some food and started eating, weapons in front of them. While Costas spoke with him, I went around the village to see whether it was surrounded. I did not see anyone. The Greeks in uniform were still hiding under the mulberry trees. The other soldier was still in sight, standing on the road at the same distance as before. I went back to sit with the group, which was still talking. The bandit sent the boy to fetch the Greek soldier who, he said, was looking for his lost wallet. The soldier came back with the boy, sat next to the bandit and also tucked in. After five minutes, having eaten and drunk at the fountain, they left in the direction of Koutchouk-Koumla. As they passed behind the village, they stole three of the refugees’ horses.»

The bandit, who was originally from Ghemlik, declared that “they’re all the same race”. He boasted of “having given them a difficult time, particularly of having set fire to the neighbouring villages to avenge the wrong done to Christians, especially last Wednesday’s murder of the two young Greeks, who had done nothing wrong.”

In the following days, Gehri met with the refugees. A Turkish doctor from Ghemlik told him that the Greek authorities were doing nothing for Muslim refugees. He gave the example of a girl who had been injured by a grenade when her village was sacked by Greek forces (see below). Half of her jaw had been torn off, but the soldiers forbade her from being taken to Bursa for treatment. The doctor told Gehri that he was in dire need of medical supplies, but he could not get permission to go to Constantinople to get them. He said, “The destruction is methodical, and it’s Ghemlik’s turn now”.

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Ghemlik mosque: Girl whose jaw has been blown off by a grenade thrown into the house where the women of the village had assembled. V-P-HIST-E-07067

Gehri next spoke with a Greek military doctor and his deputy. The soldiers were convinced that it was Turks who were setting fire to the villages in order to give the fact-finding mission a taste of the “so-called Greek atrocities”. According to them, Mustafa Kemal was warned of the mission’s arrival and had instructed a garrison of men stationed a few hours from Ghemlik to burn the Turkish villages. The two Greeks reasoned that “a few dozen dead Turkish devils” would have been a small price to pay in comparison to the moral and political gain that the Turks could make from a favourable investigation report. But, to Gehri’s mind, this did not hold water. The Greek army had been present in the region for several months and had every opportunity to set fire to the villages if they so wished. Gehri seems to have been convinced that Kemal’s forces would not be so bold as to set fire to the villages the same day there was a mission of Allied officers in the vicinity. Doubt lingered.

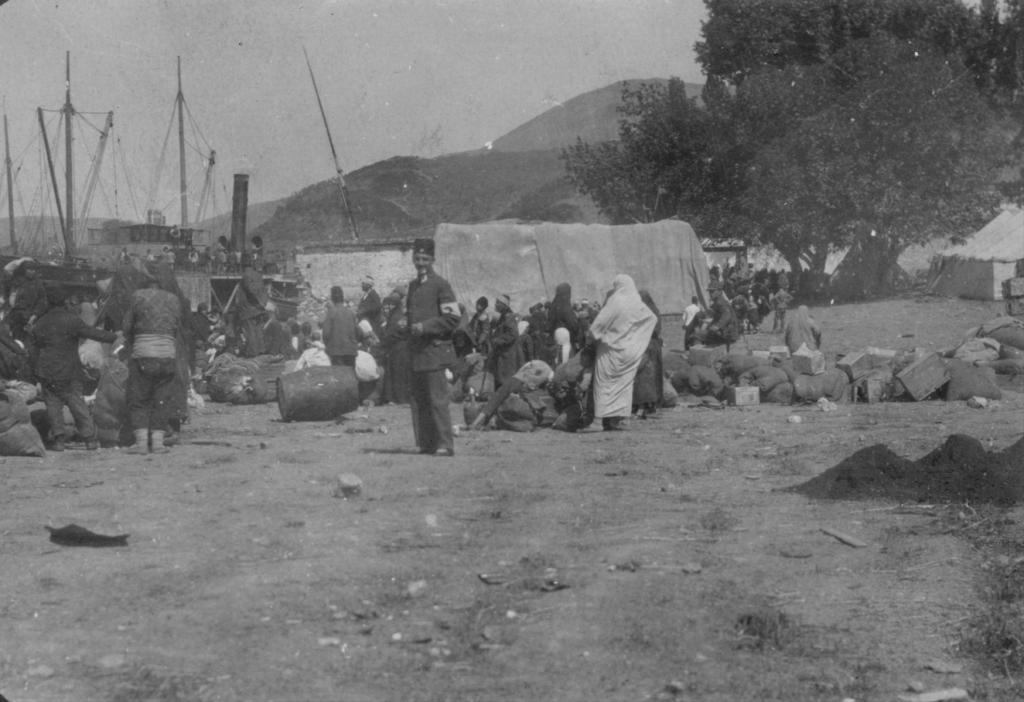

On 18 May, responding to Gehri’s appeal, the first boat from the Ottoman Red Crescent Society, the Ineboli, arrived at Koutchouk-Koumla with 850 people on board, whom it evacuated to Constantinople. On 20 May, two other ships, the Gayret and the Galata, came to help evacuate refugees. When the refugees embarked at Ghemlik, the Greek army detained all able-bodied men between 20 and 40 years old. Only the refugees who were not inhabitants of Ghemlik were allowed to board. Men were separated from their families, giving rise to painful scenes. A total of 2,660 civilians were evacuated through the work of Gehri and the Ottoman Red Crescent Society.

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Refugees on board the Galata, headed for a new location. V-P-HIST-02493-13A

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Embarkation of a group of refugees on boats, under the direction of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society. V-P-HIST-02493-12A

© Turkish Red Crescent / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish war, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: An old woman, the sole survivor of a family of twelve, aboard the Gayret. V-P-HIST-E-07114

© Turkish Red Crescent / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: The Gayret leaving Ghemlik with 250 refugees on board. V-P-HIST-E-07082

After having evacuated some of the refugees from Ghemlik – those whom the Greeks were willing to let go – the mission set sail on the Bryony to Yalova, on the other side of the peninsula. The Ottoman Red Crescent Society joined on the Gul Nihal flying the Ottoman flag, with a team led by Ali Maadjid Bey, a professor from the University of Constantinople and secretary of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society.

© Turkish Red Crescent / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, maritime route from Constantinople to Yalova: The mission on board the Gul-Nihal. From left to right: Lieutenant Holland, Lieutenant. Bonaccorsi, Captain Lucas, Ali Maadjid Bey secretary of the Ottoman Red Crescent, Maurice Gehri delegate of the ICRC, the wife of Ali Maadjid, the wife of Arnold J. Toynbee and Toynbee, a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian. V-P-HIST-E-07088

Upon arriving in Yalova on 21 May, the mission visited the city and surrounding villages. On 22 May, they decided they had concluded their fact-finding and left for Constantinople. Gehri, however, was not finished and went with the Ottoman Red Crescent Society delegates to continue evacuating the refugees of Yalova.

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, Yalova: The three Greek women killed near Samanli and exhibited in front of the konak in Yalova. V-P-HIST-E-07092

On 24 May, Gehri was told of a funeral procession being held in town for three Greek women who had been killed a few days prior in the neighbouring village of Samanli. General Leonardopoulos of the Greek forces told Gehri that the women had been killed by Turkish Kemalists. However, the delegate wrote in his diary that he had serious doubts about the circumstances of the murders. The journalist Arnold J. Toynbee observed the procession and concluded that it was staged. The procession had none of the trappings of a funeral procession: there were no relatives, no candles were lit, and the bodies were not carried, as was the custom, but instead were taken to the cemetery in a cart. Gehri wrote in his diary, “Were the women really Greek? Were they killed by Turks? Were the murderers caught? All that we’ve managed to learn is that they lived in the Armenian village nearby. There is a mystery hanging over the whole affair that we are incapable of solving. The priest from the ceremony was not from Yalova but rather was sent by the Greek patriarchate in Constantinople.” The delegate’s suspicions illustrate the difficulties that confronted him. Whom could he trust?

Gehri continued to visit villages on the peninsula. In Ak-Keuï, the villagers and Muslim refugees were terrified of bands of Greek bandits and were ready to abandon their homes and belongings just to survive.

© Turkish Red Crescent / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, Ak-Keuï: Group of refugees – blocked from boarding by the Greek authorities – alongside Lieutenant Bonaccorsi of the fact-finding mission. V-P-HIST-E-07095

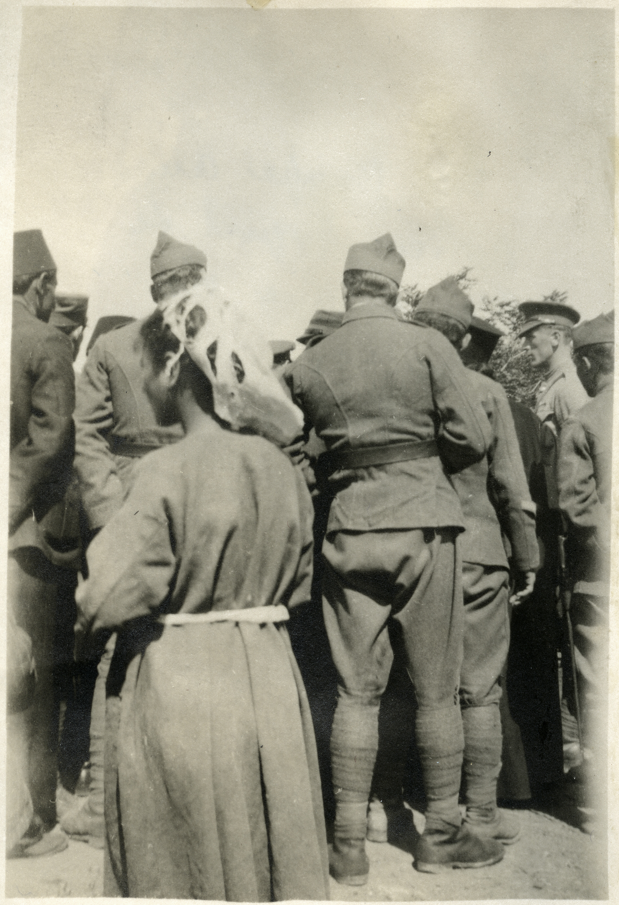

With the agreement of the Allied high commissioners, Gehri and the Ottoman Red Crescent Society organized the evacuation of the Muslim refugees from Yalova and the nearby villages. As they were boarding the Gul-Nihal, the captain of the Greek garrison at Yalova would only let those refugees leave whose villages had burned down, which he estimated to be six, while Gehri counted between fourteen and sixteen.

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, Yalova: The Greek captain Grigoriou, one of the most notorious defenders and friends of the Greek bandits of Yalova. V-P-HIST-03403-23

Gehri wrote in his diary that the ICRC had never been confronted with such difficulties and obstinacy with respect to defenceless women and children, obliging him, regretfully, to ask the ICRC headquarters to protest to the Hellenic Red Cross and to the press, which still considered Greece to be a civilized country. The suggestion to contact the press was far from the ICRC’s Fundamental Principle of neutrality, the cornerstone of the organization’s activities. One can only imagine the feeling of revulsion that Gehri must have experienced in the face of such atrocities and injustices. He wrote in his diary, “The refugees, to a one, asked to leave. The women hugged our knees. We promised to intervene on their behalf this afternoon, but we did not give them any great hope.”

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, Yalova: The Turkish governor Fuad and the Greek captain Goulas. Maurice Gehri’s caption reads: “This photograph was given to me by the governor of Yalova on 21 May as proof of the good relationship between the Turks and the Greeks prior to the recent introduction of this regime of terror and extermination.” V-P-HIST-E-07083

In his diary, Gehri made a sad assessment: The Allied powers had given the Greek army a “civilizing” mandate in Asia Minor, meaning it should therefore protect the Muslim population. To the contrary, it was systematically exterminating them. To his mind, it was becoming imperative to evacuate the whole Muslim population to Constantinople. This was confirmed when Turkish refugees from another village told him that the residents had been driven out of their houses and then crammed into trawlers that were sprayed with petrol and sunk with grenades.

In this tense climate, some of the refugees nevertheless managed to get aboard, though not without difficulty. The Greek military authorities still refused to let men between the ages of 20 and 40 go, as well as residents of Yalova and refugees from other, more distant parts of the Samanli-Dagh peninsula. Only the refugees whose villages had been burned were allowed to get on. Gehri managed with tenacity to get other villagers onto the boat. He wondered why the authorities had refused to let the refugees on: “Are they worried about what they will say when they’re out of reach, or is it revenge?”

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, Yalova: Group of refugees waiting on the beach to embark. V-P-HIST-E-07101

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, Yalova: Sorting refugees wishing to embark. The group, in which a captain’s cap and the headwear of a Greek priest can be seen, argues over a human life. V-P-HIST-E-07108

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Group of refugees waiting to board the Gul-Nihal under the supervision of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society. V-P-HIST-03403-25

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Group of refugees waiting to board the Gul-Nihal under the supervision of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society. V-P-HIST-03403-27

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Group of refugees waiting to board the Gul-Nihal under the supervision of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society. V-P-HIST-03404-02

© ICRC ARCHIVES (ARR) / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula: Group of refugees waiting to board the Gul-Nihal under the supervision of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society. V-P-HIST-03403-28

© ICRC / s.n., May 1921, Greco-Turkish War, Anatolia, Samanli-Dagh peninsula, Yalova: The Gul-Nihal. V-P-HIST-E-07089

Maurice Gehri’s mission ended on 26 May 1921, by which point 2,935 refugees (including 1,250 children) had been saved, evacuated to Constantinople. Gehri shared his feelings in a confidential note that he sent to the ICRC in Geneva. He believed that the fact-finding mission had been initiated by the British high commissioner with every intent of clearing the Greeks of the atrocities that had been attributed to them. His opinion was based not only on the attitude of the British general towards Gehri in the first few days but also on the dogged opposition of the high commissioner to bringing refugees to Constantinople. This was further supported by what Gehri had seen throughout the mission – the sympathy of the other members of the mission towards the Greeks and their rejection of the Turks.

At the close of his mission, in a report presented to the ICRC on 22 June 1921, Gehri concluded that elements of the occupying Greek army had for two months been systematically exterminating the peninsula’s Muslims. The charred villages, the massacres and the terror of the people living there left no doubt. The atrocities were the work of illegal groups of armed civilians as well as supervised army units that had not, to his knowledge, been impeded or punished by the military command. The groups, instead of being disarmed and dissolved, were seconded and supported in their actions, and they worked hand-in-hand with the regular military units.

He added that, in a relatively peaceful corner of the country that had been untouched by war before late March 1921, the Greek general Leonardopoulos, who had a duty to protect the area, had allowed revolting crimes to be committed against Muslim civilians. Gehri wondered what the reason was for his indifference: To make the Muslims pay for the second battle of Inönü (referred to by Gehri as the “defeat of Eski-Chérir”, the first major defeat of the Greek military forces) in which the general had taken part? Or was it to eliminate the Muslim population on the peninsula in order to have a Greek majority for a referendum, which was in vogue at the time, and annex the territory? Gehri wrote that 25,000 Muslims lived on the peninsula before Leonardopoulos’s arrival. Two months later, 60 per cent of the population had disappeared or fled.

After the fact-finding mission departed, the Ottoman Red Crescent Society, in agreement with the Allied high commissioners in Constantinople, evacuated the rest of the peninsula’s Muslims, some 7,000 people.[26]

A singular mission?

The fact-finding mission that Maurice Gehri accompanied presented many complications: after receiving the coldest of welcomes and the sense of being considered an intruder, the delegate gathered testimonies from which it was difficult to tell truth from falsehood. Gehri’s description of events sheds new light on facts that historiography has often neglected, around that which would today be deemed ethnic cleansing. In difficult working conditions and on a very short mission, the delegate kept a diary that, while certainly the result of his own experiences, is a notable attempt at objectivity.

Gehri wrote a mission report that was far different from the official report of the Allied commissioners. For political reasons, the commissioners used language in their report that soft-pedalled the actions of the Greek army while condemning the Turks. The report stated that Kemalists were roaming the peninsula while the Greek forces were keeping the peace in the territories effectively occupied by their troops.[27]

In the International Review of the Red Cross,[28] the ICRC published a version of Gehri’s report, without cutting out (almost) any of the delegate’s conclusions.

One year after the Gehri mission, the Christians of Anatolia were still at the mercy of the Kemalist forces, who were regaining territory. The violence also spread to Pontus, a region in the north-east of the Ottoman Empire, where an estimated 11,000 people were killed.[29] In September 1922, the routed Greek army left Smyrna, having been unable to defeat the Kemalists, who had set fire to the city. It was the end of the Megáli Idéa and the beginning of the Great Catastrophe (Mikrasiatiki Katastrofi) – the arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees in Greece.

Faced with a flood of refugees, the ICRC was once more called on to help. Delegate Rodolphe de Reding-Biberegg coordinated the relief mission for Greek refugees from September 1922 to July 1923, which was entirely different to the Gehri mission. The majority of refugees having abandoned everything when they fled, De Reding-Biberegg sought to encourage their autonomy by creating communal kitchens [30], entrepreneurship initiatives and host villages [30] built by the refugees themselves.

In July 1923, Greece and Türkiye signed a peace treaty in Lausanne, which delimited the boundaries of the new Turkish state and provided for a population exchange of more than 1.5 million people. Even today, hundreds of abandoned villages in Anatolia testify to Greeks’ former presence in the region. The photographs in the ICRC’s audiovisual archives, accessible online since 2016, help put faces to names and bring points on a map to life.

Bibliography

Books

- Akçam, T., Un Acte Honteux: Le Génocide Arménien et la Question de la Responsabilité Turque, trans. O. Demange, Denoël, Paris, 2008.

- Gingeras, R., Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire, 1912–1923, Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Rodogno, D., Night on Earth: A History of International Humanitarianism in the Near East, 1918–1930, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2021.

Articles

- Alpan, S.A., “But the memory remains: History, memory and the 1923 Greco-Turkish population exchange”, The Historical Review / La Revue Historique, Vol. 9, 2012, pp. 199–232.

- Altanian, M., “Dealing with the Armenian genocide”, Archives against Genocide Denialism?, Swisspeace, Basel, 2017, pp. 7–12.

- Barkey, K., and Gavrillis, G., “The Ottoman millet system: Non-territorial autonomy and its contemporary legacy”, Ethnopolitics, Vol. 15, No. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 24–42.

- Corm, G., “Géopolitique des minorités au Proche-Orient”, in Hommes et Migrations, No. 1172–1173, Jan.–Feb. 1994, pp. 7–17.

- Gaunt, D., “The complexity of the Assyrian genocide”, Genocide Studies International, Vol. 9, No. 1, Spring 2015, pp. 83–103.

- Georgelin, H., “Réunir tous les ‘Grecs’ dans un État-nation, une ‘Grande Idée’ catastrophique”, Romantisme, Vol. 131, No. 1, Jan.–March 2006, pp. 29–38.

- Gerwarth, R., and Üngör, Ü., “The Collapse of the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires and the Brutalisation of the Successor States”, Journal of Modern European History / Zeitschrift Für Moderne Europäische Geschichte / Revue d’Histoire Européenne Contemporaine, Vol. 13, No. 2, May 2015, pp. 226–248.

- ICRC, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, ICRC, Geneva, 1877. all sources consulted 13 March 2023.

- ICRC, L’expérience du Comité International de la Croix-Rouge en Matière de Secours Internationaux, ICRC, Geneva, 1925.

- International Review of the Red Cross, “Mission d’Enquête en Anatolie, 12–22 Mai 1921”, Vol. 3, No. 31, July 1921, pp. 721–735.

- Klapsis, A., “Violent uprooting and forced migration: A demographic analysis of the Greek populations of Asia Minor, Pontus and Eastern Thrace”, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 50, No. 4, May 2014, pp. 622–639.

- Loucas, I., “La question d’orient et la géopolitique de l’espace européen du sud-est”, Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains, Vol. 217, No. 1, Jan. 2005, pp. 17–28.

- Meichanetsidis, V.T., “The genocide of the Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, 1913–1923: A comprehensive overview”, Genocide Studies International, Vol. 9, No. 1, Spring 2015, pp. 104–173.

Archives

- ACICR, B MIS. 055-5.03, letter from the Ottoman Red Crescent society to the ICRC, 22 April 1921.

- ACICR, B MIS. 055-5-014, Mission d’Enquête en Anatolie, Maurice Gehri, Journal de Bord, 12–16 May 1921.

- ACIRC, B MIS 55.5/22, letter from the vice-president of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society to the president of the ICRC, 15 July 1921.

- ICRC Audiovisual Archives: Greco-Turkish conflict photo folder.

[1] S.A. Alpan, “But the memory remains: History, memory and the 1923 Greco-Turkish population exchange”, The Historical Review / La Revue Historique, Vol. 9, 2012, pp. 199–232. Available online: https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.295

[2] A. Klapsis, “Violent uprooting and forced migration: A demographic analysis of the Greek populations of Asia Minor, Pontus and Eastern Thrace”, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 50, No. 4, May 2014, pp. 622–639. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2014.901218

[3] Alpan, Ibid.

[*] Translator’s note: This article preserves the French phonetic spellings of place names used by Maurice Gehri so that readers may situate themselves using Gehri’s hand-drawn mission itinerary (see image).

[4] For more information on the millet system, see: K. Barkey and G. Gavrillis, “The Ottoman millet system: Non-territorial autonomy and its contemporary legacy”, Ethnopolitics, Vol. 15, No. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 24–42. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2015.1101845

[5] ICRC, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, ICRC, Geneva, 1877, p. 34. Available online: https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/S1816967800027918a.pdf

[6] In diplomatic history, the “Eastern question” was the conflict that arose between the great powers and the countries of South-Eastern Europe over the territorial division of the Ottoman Empire. See: I. Loucas, “La question d’orient et la géopolitique de l’espace européen du sud-est”, Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains, Vol. 217, No. 1, Jan. 2005, pp. 17–28. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3917/gmcc.217.0017

[7] G. Corm, “Géopolitique des minorités au Proche-Orient”, in Hommes et Migrations, No. 1172–1173, Jan.–Feb. 1994, pp. 7–17. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3406/homig.1994.2138

[8] Agreements between the French monarchy and the Ottoman sultan granting the French king’s subjects rights of trade and settlement in the Empire. See: Ibid.

[9] Pan-Islamism is a political ideology that calls for the unification of all Muslim communities. See: T. Akçam, Un Acte Honteux: Le Génocide Arménien et la Question de la Responsabilité Turque, trans. O. Demange, Denoël, Paris, 2008, p. 55.

[10] In the same vein as Pan-Islamism, Pan-Turkism is a nationalist ideology that aims for the unification of Turkic peoples. See: Idem, p. 60.

[11] D. Bloxham, The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005. Cited in: D. Gaunt, “The complexity of the Assyrian genocide”, Genocide Studies International, Vol. 9, No. 1, Spring 2015, pp. 83–103. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3138/gsi.9.1.05

[12] The Hamidian massacres were a series of Armenian revolts which were violently subdued by local Muslim militias supported by Sultan Abdul Hamid II. See: Akçam, p. 69; D. Rodogno, Night on Earth: A History of International Humanitarianism in the Near East, 1918–1930, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2021, p. 55.

[13] The massacres were perpetrated by Turks against Adana’s Christians. They stemmed from the rise of Turkish nationalism and the belief that Christians were wealthy and under the sway of European powers. See: Akçam, p. 69.

[14] Ibid.

[15] V.T. Meichanetsidis, “The genocide of the Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, 1913–1923: A comprehensive overview”, Genocide Studies International, Vol. 9, No. 1, Spring 2015, pp. 104–173. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26986016

[16] The treaty of Sèvres was seen by the Turks as an Allied plan to divide up the Ottoman Empire and a threat to nationalist objectives because it drew new borders and granted autonomy to the Kurds and Armenians. The treaty also contained a number of provisions for the victims of the massacres and deportations, including a declaration of the Ottoman government’s responsibility in the matter. See: M. Altanian, “Dealing with the Armenian genocide”, Archives against Genocide Denialism?, Swisspeace, Basel, 2017, pp. 7–12. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11066.5

[17] The Megáli Idéa was a nationalist ideology that sought to reunite Greek populations in a single Greek nation-state. See: H. Georgelin, “Réunir tous les ‘Grecs’ dans un État-nation, une ‘Grande Idée’ catastrophique”, Romantisme, Vol. 131, No. 1, Jan.–March 2006, pp. 29–38. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3917/rom.131.0029

[18] Rodogno, p. 56. In 2019, Davide Rodogno, professor of international history and politics at the Geneva Graduate Institute, published Night on Earth, which traces the history of humanitarianism in the Near East between 1918 and 1930. The book greatly advanced the effort to shed light on this sometimes-neglected era in Greco-Turkish history. Rodogno consulted the ICRC’s general public archives as part of his research, and his work addresses two ICRC missions: Gehri’s 1921 mission, and that of De Reding-Biberegg in 1922 to 1923, which was aimed at helping Greek refugees arriving from Asia Minor.

[19] Meichanetsidis.

[20] ICRC, L’expérience du Comité International de la Croix-Rouge en Matière de Secours Internationaux, ICRC, Geneva, 1925, p. 37.

[21] R. Gingeras, Sorrowful Shores: Violence, Ethnicity, and the End of the Ottoman Empire, 1912–1923, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 200.

[22] Rodogno, p. 202

[23] ACICR, B MIS. 055-5.03, letter from the Ottoman Red Crescent Society to the ICRC, 22 April 1921.

[24] ACICR, B MIS. 055-5.014, Mission d’Enquête en Anatolie, Maurice Gehri, Journal de Bord, 12–16 May 1921.

[25] ACICR, B AG MIS. 055-5.014, Ibid.

[26] ACIRC, B MIS 55.5/22, letter from the vice-president of the Ottoman Red Crescent Society to the president of the ICRC, 15 juillet 1921.

[27] Rodogno, p. 211.

[28] The International Review of the Red Cross is one of the oldest publications dedicated to humanitarian law, policy and activities. It has been the official periodical of the ICRC since 1869.

[29] R. Gerwarth and Ü. Üngör, “The Collapse of the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires and the Brutalisation of the Successor States”, Journal of Modern European History / Zeitschrift Für Moderne Europäische Geschichte / Revue d’Histoire Européenne Contemporaine, Vol. 13, No. 2, May 2015, pp. 226–248. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26266180

[30] Deux films issus de la collection des archives audiovisuelles du CICR illustrent la mission De Reding-Biberegg.

https://avarchives.icrc.org/Film/5445

https://avarchives.icrc.org/Film/5447

I live in that region, the pain is still fresh.. shame on humanity like this