In 2022, the ICRC archives with the support of the Arolsen Archives launched an effort to digitize the Drancy file, with the aim of making the documents available online to researchers around the world. The Arolsen Archives – an international centre on Nazi persecution located in Bad Arolsen, Germany – are funding the digitization of the archives and will incorporate them into the collaborative digitization project #everynamecounts.

The documents in the ICRC’s Agency archives are at once both unique and universal: They protect the memory of the identities, experiences and suffering of victims of conflict, but they also resonate personally within each of us.

Some, however, are particularly evocative. The Drancy file is among them. The file contains information on approximately 35,000 Jewish deportees of various nationalities who were arrested by the Vichy government on French territory and kept in the internment camp in Drancy, France, between February 1942 and March 1943.

The Drancy camp was made up of a large tract of low-cost housing. From September 1939 to June 1940, the French government used it as a detention centre for communists. After the armistice in June 1940, German authorities turned it into an internment camp for prisoners of war as well as French, British, Yugoslav and Greek civilians. From 21 August 1941, the Drancy camp was the primary internment camp for Jews in France.

The camp was run by the Seine police prefecture and overseen by German authorities until 2 July 1943, when the Nazi security services took over.

Nearly 70,000 people were interned at Drancy between August 1941 and August 1944; from 22 June 1942, the majority were deported to the extermination camps at Auschwitz (around 61,000 people) and Sobibor (around 4,000).

World War II. Drancy. Camp for Jewish civilian internees. Inner courtyard and buildings. V-P-HIST-00729-07A

Life in the camp

The living conditions for the camp’s first detainees were gruelling. They were starved and subjected to extreme physical and mental isolation. André Baur, an internee, remarked that after one month in the camp some men had lost more than 30 kilograms. The historians Annette Wieviorka and Michel Laffitte write that the straits of internees at Drancy recall those of the people penned in Polish ghettos, with the Germans providing them with far less food than they needed to survive.[1]

World War II. Drancy. Camp for Jewish civilian internees. Waiting in front of the kitchen at mealtime. V-P-HIST-00729-03A

Proof of deportations

In July 1942, only men were being arrested and deported. After the Wannsee Conference, when the so-called Final Solution was set into motion, the number of deportations rose. On 19 July 1942, 1,000 people were deported, this time including women and children. Through September, there were three deportations each week – on Sundays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays. From October 1942 to July 1943, 15,000 people were deported.

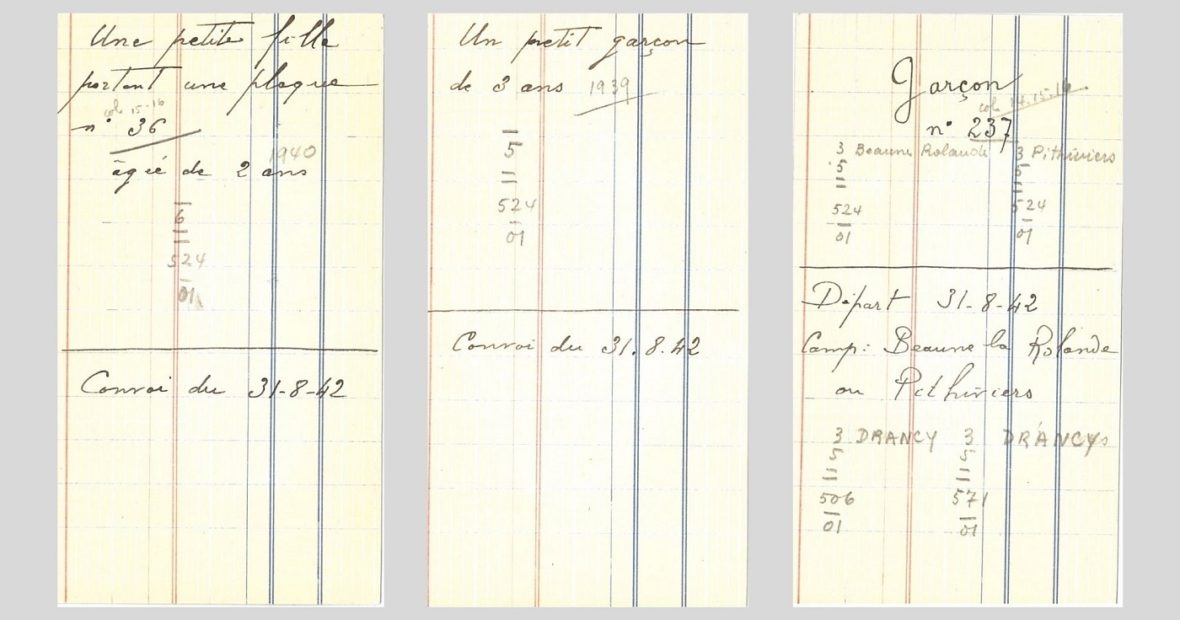

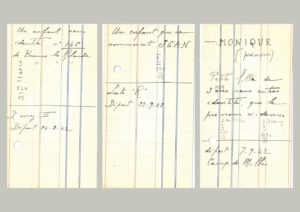

The documents in the Drancy file bear witness to how entire families were deported. Fathers, mothers, children, pregnant women, the elderly, disabled and ill people, newborns – no one escaped the mechanism of destruction put into motion by the Nazis with the active collaboration of the Vichy government.

The documents

The Drancy file comprises small cards, around 6.5 by 12 centimetres, usually printed with forms that were then filled out by hand. Not every card was filled out completely, but the information on them might include the detainee’s given and family names, address, date and place of birth, nationality, date of arrest, place of interment, place and date of departure, whether the detainee was arrested in an occupied or unoccupied zone, and additional notes. Camp personnel filled out a card for each internee when they arrived. When they were deported, the date of deportation was added to the card.

The file contains cards for Jews from France, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Poland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Greece and Turkey. The documents in the ICRC archives are only one part of the much larger Drancy file. The French National Archives maintain the complete file.[2]

Conserving the file

The documents were sent to the ICRC by the French Red Cross in several batches between June and September 1943. Unfortunately, the other details and circumstances of the transfer are unknown. The documents must have been hidden by internees and removed by someone on the outside. In a note in George Kohn’s Journal de Compiègne et de Drancy, Serge Klarsfeld suggests several possibilities. On 5 August 1943, Jean Mayer, the head of the camp’s military office, met with several people at the Swiss consulate. Was this how the Drancy file made its way out? Or was it sent with the aid of Marcel Stora of the General Union of French Jews (Union Générale des Israélites de France)? [3]

Once it arrived at the ICRC, the Drancy file was sent to the part of the Central Agency for Prisoners of War responsible for handling civilians’ cases, the Service des Civils Internés Divers (CID).

In 1943, the CID began to send the cards out to the various national sections, only keeping those for German and Austrian Jews, who had been stripped of their nationalities. The file is therefore spread out among the archives of various parts of the agency. Over time, the cards in the Drancy file were mixed in with other documents and gradually forgotten. Archivists rediscovered them in the course of research carried out for Serge Klarsfeld in 1996.

The fate of the children

Following the files for stateless Germans and Austrians are a particularly heart-rending series of cards: those for unidentified children, deported without their parents and too young to know their own names. The children were almost certainly arrested along with their families during the Vélodrome d’Hiver roundup, on 16 July 1942, and transferred to the Beaune-la-Rolande camp, in Loiret, where they lived in appalling conditions. At the end of July, the adults and adolescents were deported. Only the children remained, alone and hopeless, until they were transferred to Drancy in August 1942 before being deported to an extermination camp.

Drancy internee Odette Daltroff-Baticle wrote in 1943, “We are surprised by something tragic: the children do not know their own names …. The first and last names and addresses their mothers had written on their clothes had completely disappeared from the rain, and other children, either in a game or by accident, had traded clothes. On the lists, next to their numbers were question marks”.[4]

The Red Cross’s work

In October 1941, the French Red Cross got access to the Drancy camp and assigned the social worker Annette Monod to work with the internees. She established social services, a library, a game room and a Jewish place of worship. She visited the families of internees and passed on clothing, packages and news. The German authorities disapproved of her assiduousness and shut down the Red Cross branch on 16 February 1942. From that point, only the General Union of French Jews was able to bring aid to the camp.

In May 1943, Adolf Eichmann, who organized the Final Solution, put the Nazi security services (SS) officer Alois Brunner in charge of Drancy and directed him to speed the pace of deportations. The French police were pushed out of the camp, leaving only the SS in charge.

After visiting Drancy on 10 May 1944, the ICRC delegate Jacques de Morsier wrote a report on his visit; what it depicts is far different to what is now known to have been the reality of the period. With regard to Brunner, de Morsier writes: “The beginning of his tenure was fairly difficult because he wanted to eliminate habits that had made life in the camp quite impossible …. Captain Brunner has removed all money from inside the camp: when an internee arrives, their money and jewellery are placed in a safe in the camp’s financial service (managed by the internees themselves) against receipt, with the promise they will be returned upon the internee’s release.”

Of course, the reality was far different. The detainees would never reclaim their money, and deportations continued up to the liberation of Paris. The final convoy of 51 deportees left Drancy on 17 August 1944 – the day the camp was liberated – for Buchenwald.

The Drancy file is a significant collection in the ICRC’s archives: it serves as written testimony to the tragic fate of tens of thousands of people. Digitizing the Drancy file as part of the collaboration with the Arolsen Archives will give the general public easy access to these important documents. Because every name counts.

Bibliography

Calef, N., Drancy 1941: Camp de Représailles, Drancy la Faim, Fils et Filles de Déportés Juifs de France (FFDJF), Paris, 1991.

Favez, J.-C., Une Mission Impossible? Le CICR, les Déportations et les Camps de Concentration Nazis, Payot, Paris, 1988.

Klarsfeld, S., Le Calendrier de la Persécution des Juifs de France: 1940–1944, FFDJF / The Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, Paris / New York, 1993.

Klarsfeld, S., Collection of publications by the FFDJF [13 documents, including Kohn, G., “Journal de Compiègne et de Drancy”], 1995.

Peschanski, D., La France des Camps: L’Internement, 1938–1946, Gallimard, Paris, 2002.

Wieviorka, A., Laffitte, M., À l’Intérieur du Camp de Drancy, Perrin, Paris, 2012.

[1]Annette Wieviorka, Michel Laffitte, À l’intérieur du camp de Drancy, [Paris] : Perrin, 2012, p.36.

[2] These archives on microfilm are kept on the Pierrefitte-sur-Seine site. The originals were deposited at the Shoah Memorial.

[3] Journal de Compiègne et de Drancy, by Georges Kohn, p.222 and note 80.

[4]Testimony of Odette Daltroff-Baticle written in 1943 and published in S. Klarsfeld, Le Calendrier, 1993, pp. 404-407.

Thank you for keeping the memory alive.