In the course of the Second World War, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) made several motion pictures with which it sought to “make the meaning of its work and of the Red Cross known through films which would directly appeal to the public”.[1] These productions include The flag of mercy (1942) et One way remains open ! (1944), which illustrate the work of the Central Prisoners of War Agency. In 1944, two other documentaries were made: Deutsche Kriegsgefangenen in einem Arbeitslager in Kanada about the daily lives of German prisoners of war and civilian internees in Canada and Ein Soldat wird vermisst which features dramatized scenes depicting the Agency’s efforts to reunite a soldier with his family. Lastly, Prisonnier de guerre…, the subject of this article, was made in early 1945.[2] It is a fictional story about the harrowing day-to-day existence of prisoners of war held in camps grappling with a condition dubbed “barbed-wire disease” at the time. There are many questions surrounding this film about the circumstances of its creation and its form and content. The article begins with a look at the context of the film’s development and production, continuing with an analysis of various aspects of its content.

Production context

After searching the ICRC’s archival records and secondary literature, it became clear that very little documentation exists on Prisonnier de guerre…. Nevertheless, the following insights can be drawn from the few records preserved in the archives and various other sources, such as news articles.[3]

Why this film ?

The intention was to show the film, made in early 1945, as part of a travelling exhibition organized by the ICRC. The exhibition, entitled Captivity, provided the Swiss public with a vivid portrait of the harsh reality of life for prisoners of war in enemy hands during the Second World War.[4] The exhibits included carvings, pictures, model boats, musical instruments and other objects, conjuring up in the minds of visitors the long empty days in captivity that prisoners needed to fill with activities to pass the time. Ciné-Journal suisse devoted an episode in German to the exhibition, which is preserved in the archives[5]. It features the objects made by the prisoners but, surprisingly, makes no mention of the showing of Prisonnier de guerre… as part of the exhibition.

Kriegsgefangene [Aus Gefangenen-Lagern] (© Ciné-Journal suisse; 1945; V-F-CR-H-00057) 00:01:06:00 – 00:01:45:00

The film was, however, mentioned in several news articles:

“Finally, you go into the cinema room where an exquisite film invites the spectator to see and feel how a black mood, known as barbed-wire disease, takes hold of prisoners and to experience their unceasing struggle to keep this terrible psychosis at bay.” [6]

Articles were published on the exhibition in regional newspapers as it toured the country, revealing that, after Zurich, it made stops in the cities of Geneva, Fribourg and La Chaux-de-Fonds.[7]

Production

Although the main reason for producing the film in early 1945 was the travelling exhibition, there is no indication of the motivation behind the ICRC’s choice of script and type of film. The organization normally made documentaries, and it was unusual for it to opt for a fiction film. The Zurich-based production company, Central-Film SA, which had already made One way remains open !, released in March 1944, was commissioned by the ICRC at the outset for both the writing of the script and the shooting and editing of the film. Discussions about the film, which apparently began in 1944, were mainly between Hans de Wattenwyl, director of the ICRC’s Information Department, and Central-Film director Paul Meyer. The correspondence between them stored in the archives, while not exhaustive, does shed light on some aspects of the circumstances surrounding its production.

Prisonnier de guerre… was finely crafted by the film’s director, Kurt Früh. This was not his first film for the ICRC; he had already co-directed two documentaries – The flag of mercy and One way remains open !.[8] He was also assigned to write the script with Umberto Bolzi. For this purpose, they apparently met with ICRC delegate Dr Marti,[9] and the script they developed is, in fact, inspired by a field visit report written by a delegate, in all likelihood this same doctor.[10]

Financing

The absence of details in the archives about the funding of the film makes it impossible to ascertain what financial contribution each party made. Some documents refer to a significant contribution from Central-Film: “our production team will make every effort to produce a film of the highest quality as their work is crucial to recovering the significant financial contribution we have made”.[11] There are, however, other documents that highlight the contribution made by the ICRC: “this film was commissioned by the International Committee of the Red Cross, which is covering most of the cost of making the film; the rest is being financed by Central-Film”.[12]

Just five months elapsed between the first mention of Prisonnier de guerre… in the archives and the date of the premiere. Although at the start of these exchanges Central-Film was very enthusiastic about the idea of making the film, motivated by the prospect of capitalizing on future opportunities,[13] it seems that in the ensuing months relations between the two organizations cooled. The budget was undoubtedly the main sticking point, with the film requiring significant financial resources. The ICRC’s failure to have Paul Meyer’s visa application fast-tracked so that he could negotiate the distribution of the film abroad would have been another bone of contention. The Central-Film director expressed his impatience in numerous exchanges with the ICRC:

“Now that the ceasefire has been declared, it is even more urgent to ensure the early release of the Red Cross film “Prisonnier de guerre…” as it is becoming more and more outdated and therefore losing its value.”[14]

For unknown reasons, attempts to obtain the visa through the ICRC – supposedly to speed up the process – dragged on, and when Paul Meyer was finally able to go to France, the moment for promoting the film had passed. This meant that its distribution – and box-office takings – were not as good as expected.[15]

It remains unclear how the costs and revenues of Prisonnier de guerre… were shared between the ICRC and Central-Film although it is probably safe to assume that the film racked up considerable losses for all concerned.

It can be concluded from this analysis of the context that the film was written, shot and edited in record time so that it would be ready to be shown during the travelling exhibition scheduled to start on 4 May 1945 in Zurich. However, with the issues addressed in the film soon overtaken by events as the war drew to a close, the production did not live up to expectations in terms of the revenue it earned abroad in the months following its release.

Efforts to promote Prisonnier de guerre… included it being entered in the first edition of the Cannes Film Festival in 1946, where it competed in the short film category.[16]

The Film

What is Prisonnier de guerre… about ?

As its title suggests, this fiction film is about prisoners of war held in a camp. In the almost 28 minutes that it lasts, the film shows the day-to-day existence of a group of men who, cut off from the world, endure the endless succession of days, slipping by one after the other, without knowing when they will regain their freedom. The film follows several characters, the main ones played by Guy Tréjan, Jacques Mancier and William Jacques,[17] all at the start of their acting career at that time. Each of the men, with their distinct character, state of mind and actions, plays a specific role, portraying life in the camp, interactions between the prisoners and the effect of captivity on morale.

The action is set in a prisoner-of-war camp, with alternating scenes of the prisoners in the barracks and working outdoors.[18] The film reveals nothing about the background of the prisoners or their guards, whose faces are almost never seen on the screen. The time and place also remain unspecified.[19] This manifestly deliberate haziness is a nod to the principle of universality advocated by the ICRC and emphasizes that what is at the heart of the film is the man as a captive, not the context in which he came to be a prisoner.

As mentioned earlier, the film is inspired by a report written by an ICRC delegate on barbed-wire disease, a psychosis that affects people held captive for long periods. This is the thread that weaves through the story. An article published in 1918 in the Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge explains that the main causes of this syndrome, also known as cafard or “black mood”, are physical confinement, lack of privacy and uncertainty about how long their captivity will last.[20] This psychological condition affecting captives, already observed during the Great War, reappeared in the Second World War when several million soldiers and officers were confined in camps.

The main factor contributing to the development of barbed-wire disease among prisoners in captivity is the struggle with time. According to historian Annette Becker, “[p]hysical and mental sufferings are increased and multiplied by the duration of time […] But the prolongation in captivity […] eats away at the most tenacious hopes”.[21] Prisoners did their best to keep occupied, each in their own way, in an attempt to kill time, forget about their grim situation and escape from the day-to-day hardships of life in the camp. Material and intellectual distractions were a refuge from boredom and helped the prisoners cope with the monotony of confinement and the long dreary days.[22] The film addresses this syndrome and the notion of time through different means, including the script, the mise-en-scène and cinematographic devices. There follows an overview of the elements used to draw the spectator into the prisoner of war’s day-to-day existence.

Mise-en-scène and dialogues

The script is painstakingly crafted to paint as real a picture as possible of how the prisoners lived in captivity and with each other. The characters, in stereotypical roles, interact in their common struggle to stave off a descent into despondency. Each of them, with their own moods and pastimes, plays a distinct role in carrying the story told in the film. Some play cards or read, while others form a “club” to discuss the future or carve the days on a block of wood. Although they are all assailed by feelings of gloom and boredom, there is a marked contrast between several characters who are very pessimistic and others who are more optimistic.

The main character, a young architect called Pierre, is a good example. From the start of the film, he shows signs of despair and weariness. His remarks reflect his highly pessimistic view of the future, and he seems resigned to the grim reality of his situation.

Prisonnier de guerre… (© ICRC; Kurt Früh; 1945; V-F-CR-H-00042) 00:15:16:00 – 00:15:57:12

On several occasions, his fellow prisoners try to raise his spirits, as when Jean says to him:

“You’re sinking, old chap. You’re sinking into despair. You’ve got to do something. Prepare for the future.”[23]

Preparing for the future is the last thing on Pierre’s mind; he has lost faith in the future. He remarks, with bitter incisiveness, that he cannot see the point in “building cities just to bomb them into oblivion”.[24] The fact that he is an architect by profession seems to heighten his disillusionment with the future. However, during the film Pierre has a watershed moment, and his attitude gradually changes. Little by little, he regains his purpose, joining his comrades to discuss the reconstruction of cities that have been destroyed. He takes his place at the centre of the table to lead the deliberations, perhaps because he is more qualified than his fellow sufferers. Using his knowledge to contribute to the debate on tomorrow’s world seems to kickstart Pierre back to life.

The character called Paul is another example of a man quick to give in to feelings of hopelessness. In the first part of the film, he articulates his qualms about his own worth :

Paul: “I used to be a violinist in an orchestra. Without my instrument, I am worth no more than a flea.”

Jean : “But you know you’re going to get a violin. The delegate promised you one.”[25]

When Paul finally receives the long-awaited violin, seemingly in the grip of despair, he no longer has any desire to play it. At the end of the film, when several of the characters regain a sense of hope, the sound of a violin fills the air – Paul has taken up his bow and started to play (see sequence 4). The melody emanating from the violin suggests that he has found a glimmer of hope. In the latter scenes, there is, overall, a more positive attitude among the prisoners, who seem to have managed to overcome the sense of despondency gnawing at them in the earlier part of the film.

Narration

Apart from the dialogue among the characters, the film also has an omniscient narrator who conveys the atmosphere in the camp and the prisoners’ thoughts and concerns in a way that could almost be described as poetic. The narrator even addresses the prisoners directly at some points in the film.

The narrator’s words are sombre, grave and repetitive although the tone lightens somewhat as the film progresses. The narration is constructed, both in content and form, with a rhythmic drive that heightens the sense of monotony and the seconds ticking by. The spectator is assailed by a barrage of repetitions, orders bellowed by the guards and certain terms, such as “barbed wire”, a constant reminder of the prisoners’ captive state. In the excerpt below, for example, the narrator’s words accentuate the endless repetition of days, highlighting the sense of time passing… or not passing.

Prisonnier de guerre… (© ICRC; Kurt Früh; 1945; V-F-CR-H-00042) 00:08:07:00 – 00:09:00:12

Along with this solemn discourse, the narrator also conveys a reassuring message to the prisoners :

Prisonnier de guerre… (© ICRC; Kurt Früh; 1945; V-F-CR-H-00042) 00:27:08:24 – 00:28:01:00

Immediately after this outpouring of hope to the strains of the violin, the voices of the guards erupt as a harsh reminder of the men’s captivity. Although the characters show a spirit of optimism, they are still imprisoned, and the narrator’s final words are a last echo of the monotonous succession of days and months of confinement in the camp.

“After a grey day, another grey day, and time, in its dreary greyness, passes or doesn’t pass. Monday, Tuesday. May, November.”[26]

Cinematographic devices

In any film production, aesthetics plays an important role. Through a film’s sound and visuals, it conveys information and sensations to the spectators, whether they are conscious of it or not.

Prisonnier de guerre… was filmed in black and white. From the start, shades of black dominate the images in a striking manner. Dark hues abound, and the contrast between black and white is arrestingly stark. This gloomy atmosphere is not the result of chance or poor image quality, but a deliberate strategy employed by Kurt Früh to heighten the gravity and solemnity of the film.

The music and sound effects also have an important role, adding intensity to the scenes. The sound track is used as an additional device to accentuate the feeling of icy coldness and monotony already suggested by other means. The drum beat running through almost the entire film – amplified in the marching scenes and when the guards belt out orders – marks the relentless rhythm of the seconds ticking by, an effect that can be observed in the following excerpt.

Prisonnier de guerre… (© ICRC; Kurt Früh; 1945; V-F-CR-H-00042) 00:06:03:15 – 00:06:38:22

Through the different elements described above (dialogue, narration, and sound and visual aesthetics), the spectator is drawn into the everyday existence of the prisoners. This glimpse into prison camp life reveals the prisoners’ state of mind as they claw their way from despair to hope, from weariness to enthusiasm, regaining a taste for life and faith in the future.

The ICRC in the film

The fact that the film was commissioned by the ICRC leads to the obvious question of how the organization features in the story. After the opening credits, this introductory caption appears on the screen:

“While this film is not a documentary, it is based on a report written by a delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross about the psychological condition referred to as “barbed-wire disease”, rife in prisoner-of-war camps. With this free screen adaptation of elements from the report, this film endeavours to show how relief activities carried out by the ICRC and other relief organizations for prisoners of war help to keep barbed-wire disease at bay.” Prisonnier de guerre… (© ICRC; Kurt Früh; 1945; V-F-CR-H-00042) 00:02:36:11 – 00:02:51:24

“While this film is not a documentary, it is based on a report written by a delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross about the psychological condition referred to as “barbed-wire disease”, rife in prisoner-of-war camps. With this free screen adaptation of elements from the report, this film endeavours to show how relief activities carried out by the ICRC and other relief organizations for prisoners of war help to keep barbed-wire disease at bay.” Prisonnier de guerre… (© ICRC; Kurt Früh; 1945; V-F-CR-H-00042) 00:02:36:11 – 00:02:51:24

After this first mention, the film starts, setting the scene for the action, and the ICRC does not feature again until around ten minutes into the film, when the narrator explains that:

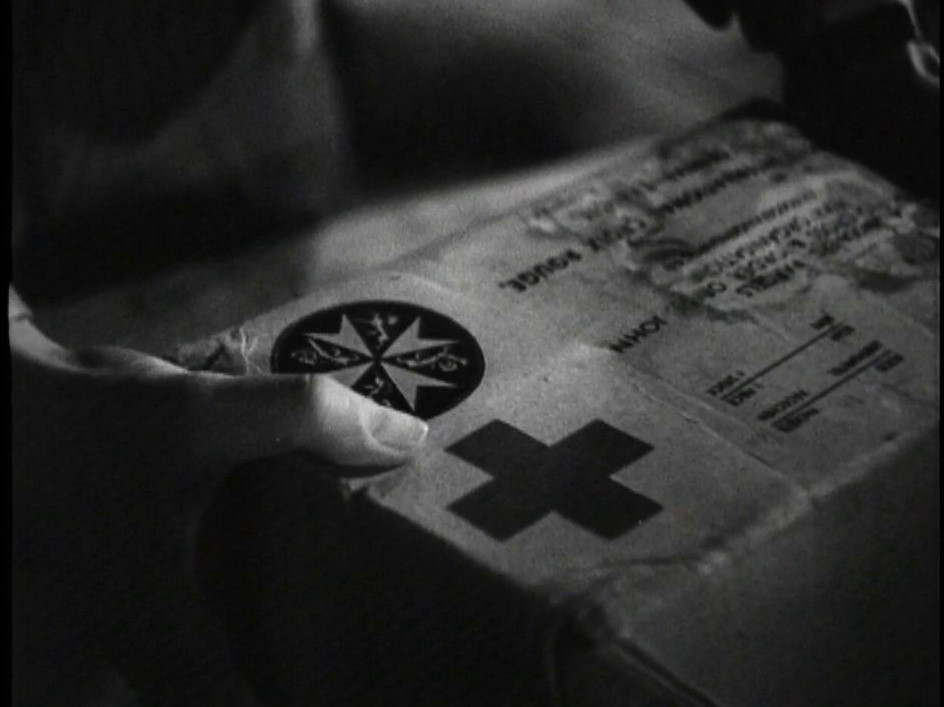

“millions of packages are shipped around the world to prisoners of war. Millions of packages sent via the only way that remains open: the Red Cross services that reach everyone with these humble messages from home”.[27]

During the course of the film, the subject of packages for prisoners crops up in several scenes, without being the central focus. Jean and Pierre twice refer to a “delegate” who probably visited their camp and took their requests for specific items, such as the violin for Paul, spectacles and books on architecture. Although the film only touches on the subject, it endeavours to show that the work of the ICRC (and other relief organizations) has a beneficial effect on prisoner morale and goes some way to alleviating their suffering.

The question of what the ICRC hoped to convey through this fiction film, made as the war was drawing to a close, in addition to the purpose it had as part of the travelling exhibition, is one that warrants attention. With its focus on the characters and their state of mind, it aims to make the general public aware of the conditions endured by prisoners held in captivity for long periods. With its brief mentions of the ICRC’s work, it seeks to show how the organization comes to the aid of prisoners of war in an attempt to alleviate, in some small way, their physical, mental and emotional distress. It may also have been the ICRC’s intention, in raising the awareness of the general public, particularly the Swiss public, to encourage donations.

Conclusion

As we have already seen, Prisonnier de guerre… is an atypical production in that it departs, in several respects, from the type of film usually made by the ICRC. First, it differs in terms of its purpose; it was made to be shown as part of the travelling Captivity exhibition on the conditions endured by prisoners of war confined in camps. In this regard, it should also be noted that it is one of the first films that puts the beneficiaries of humanitarian action in the spotlight, leaving the organization in the shadows. The fact that it is a fiction film shot entirely with actors on a set is also a novelty.

However, the research carried out for this article leaves numerous questions unanswered. Taking into account that the film was made towards the end of the war, did it achieve its aim of raising public awareness? Was the ICRC’s decision to use fiction to document the day-to-day existence of prisoners of war a wise one? Although Prisonnier de guerre… was inspired by a field visit report, it does not represent all the types of captivity that existed. It therefore risks giving too narrow an idea of what prisoner-of-war camps were like. Nevertheless, it is also true that, in 1945, fiction was the only way to show what conditions were like for prisoners of war as it was difficult, if not impossible, to film inside the camps.

In conclusion, it is clear that three-quarters of a century after it was released, Prisonnier de guerre… still has the power to fascinate, challenge and impact the spectator. Although atypical, this film is an important testament to the ICRC’s film-making endeavours and to the work of the Central Prisoners of War Agency.

[1] Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities during the Second World War (September 1, 1939–June 30, 1947), Vol. I: “General Activities”, ICRC, Geneva, 1948, p. 133.

[2] The original title, as it appears in the film, is in the singular. It is sometimes written in the plural or without quotation marks.

[3] These findings represent the current state of knowledge, and further research is required. It would, for example, be interesting to examine the records that Central-Film SA has in its archive in Zurich on this film.

[4] Die Tat, Zurich, 6 May 1945, p.3 ; Le Journal de Genève, Geneva, 26 May 1945, p.2 ; La Liberté, Fribourg, 9 June 1945, p.3 ; La Sentinelle, La Chaux-de-Fonds, 7 July 1945, p.3.

[5] ICRC Archives V-F-CR-H-00057. Unknown, Kriegsgefangene [Aus Gefangenen-Lagern], © Ciné-Journal suisse, 1945.

[6] La Sentinelle, op. cit. (quote translated).

[7] Le Journal de Genève, op. cit. ; La Sentinelle, op. cit. ; La Liberté, op. cit. ; Die Tat, op. cit.

[8] For more information on The flag of mercy, see Meier Marina, “Le drapeau de l’humanité” : a film through the lens of the Archives, ICRC, Geneva, 2016. On One way remains open ! see Meier Marina, « Note sur Une voie reste ouverte ! » in Construire la paix : journées du film historique, La Revue du Ciné-club universitaire, special issue, Geneva, 2015, pp. 15-19.

[9] ICRC Archives BG 58, 23 December 1944. Letter from Paul Meyer to Hans de Wattenwyl.

[10] The report has not been identified. A thorough search of the field visit reports preserved in the archives would be required to find it.

[11] ICRC Archives BG 58, 23 December 1944. op. cit. (quote translated).

[12] ICRC Archives BG 58, 14 April 1945. Letter from Hans de Wattenwyl to an unknown recipient (quote translated).

[13] ICRC Archives BG 58, 23 December 1944. op. cit.

[14] ICRC Archives BG 58, 14 May 1945, Letter from Paul Meyer to Martin Bodmer (quote translated).

[15] ICRC Archives BG 58, 23 December 1947, Letter from Paul Meyer to the ICRC.

[16] Cannes Film Festival official website

[17] Guy Tréjan (1921–2001) was a French-Swiss actor and comedian who worked in Geneva for some time before moving to Paris to pursue his acting career. Jacques Mancier (1913–2001) was a French comedian, actor and TV presenter. William Jacques (1917–2000) was a great Genevan comedian, director and radio man.

[18] The film was, in all probability, filmed on a set somewhere in the Zurich area.

[19] Certain details suggest that they were French prisoners held captive by the Germans since 1940, that is, for four long years.

[20] K. de Wattenville, “La psychose du fil de fer”, Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge, No. 1, Geneva, January 1919, pp. 314–315.

[21] Annette Becker, “Introduction”, in Anne-Marie Pathé and Fabien Théofilakis (eds), Wartime Captivity in the 20th Century: Archives, Stories, Memories, Berghahn Books, New York/Oxford, 2016, pp. 80–81.

[22] Cochet François, Soldats sans armes. La captivité de guerre : une approche culturelle, Bruylant, Brussels, 1998, p. 283.

[23] ICRC Archives V-F-CR-H-00042. Kurt Früh Prisonnier de guerre…, ICRC, 1945. 00:14:22:02 – 00:14:45:08 (quote translated).

[24] Ibid., 00:10:58:14 – 00:11:10:02 (quote translated).

[25] Ibid., 00:16:40:22 – 00:16:49:22 (quote translated).

[26] Ibid., 00:28:18:21 – 00:28:30:24 (quote translated).

[27] Ibid., 00:11:53:00 – 00:12:09:14. This comment refers to the film One way remains open !, produced by the ICRC the previous year (quote translated).

Comments