The ICRC Library’s collections retrace over 150 years of the history of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. Its rare books collection inherited from the ICRC founders as well as current ones offer a unique testimony to the development of humanitarian action. They also reflect the diversity of the activities of a movement working across the globe to assist victims of armed conflict and other situations of violence since 1863. These collections also include the writings of humanitarian action and law pioneers, whether they took part in the Movement’s development, inspired its action or shared its values and missions. Recently reorganized, a collection of the Library comprises the writings of these nurses, doctors, diplomats, scientists or jurists of the 19th and 20th centuries and the biographies or studies inspired by their action.

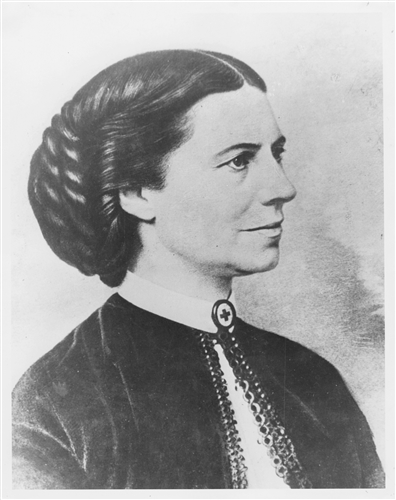

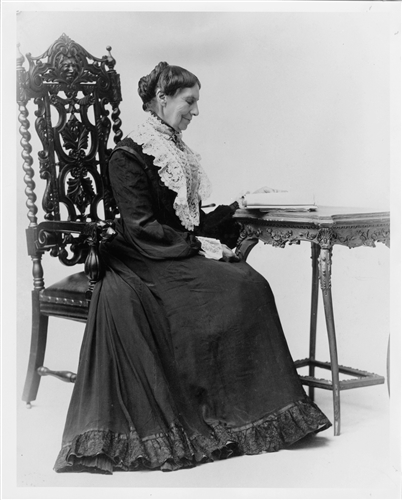

Clara Barton (1821 – 1912), founder of the American Red Cross Society and pioneer of disaster relief

“It is not in its past that the glories or the benefits of the Red Cross lie, but in the possibilities it has created for the future (…)”

– Clara Barton [1]

A true national heroine, humanitarian pioneer Clara Barton certainly left her mark in American history. Known for her assistance of wounded soldiers on the Civil War’s bloodiest battlefields, she is also truly responsible for the implementation of the principles and activities of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent in the United States. Founder of the American Red Cross Society in 1881, she adapted its activities to meet the needs of her homeland during peacetime and turned it into the primary American institution for disaster relief of the time.

« I leave immediately for the Battlefield » [2]

Born in 1821 into a family of farmers in the state of Massachusetts, Clara Barton started her career as a teacher. Moving to Bordentown, New Jersey, she founded and ran the first public school of the area. Hired in 1854 by the US patent office, she became one of the federal government’s first female clerks. Before being demoted by a new administration hostile to female employees, she was doing the same job as her male counterparts for the same pay. She interrupted her activities at the onset of the Civil War in 1861. Upon hearing that a regiment in which some of her former students were serving had been attacked, she brought food and clothing to Washington, where the Massachusetts troops were parked. This action would be the first of a long series in her tireless efforts to mitigate the sufferings caused by the war. Working in the Washington Hospital where wounded soldiers were transported, she felt that her help was systematically coming too late. She thus took the initiative to take her services directly to the battlefields, despite the reluctance of military officials to allow the presence of a woman in the middle of the shootings. On September 17th 1862, she was a direct witness to the deadliest military campaign in US history, the Battle of Antietam. Her initiative, courage and expertise were there of invaluable help to the overwhelmed military medical services of the Union forces. Because she had brought candles, war surgeons were able to keep working after dusk. Recounting his experience at Antietam, surgeon James Dunn wrote that “in [his] feeble estimation, Gen. McLellan, with all his laurels, sinks into insignificance beside the true heroine of the age : the angel of the battlefield”. [3] Her action, related in newspapers across the country, attracted a lot of publicity.

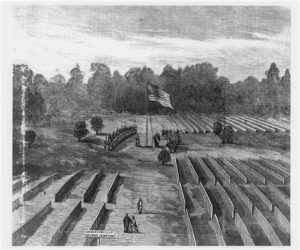

Back in Washington at the end of the war, Clara Barton sought and obtained President Lincoln’s support to act in favour of former prisoners, to try and reunite the families separated by the war. For two years, she collected requests for information sent in by relatives, compiled lists of missing soldiers and had them printed in newspapers and displayed in every town and village of the region. Her inquiry service was soon overwhelmed by the number of requests received and she mobilized considerable resources to carry out her work, including much of her personal savings. [4]

While imprisoned, young Union soldier Dorence Atwater made a secret copy of his captors’ death registers, writing down the names and burial sites of the more than 13’000 northern prisoners that had died in Andersonville, Georgia. He handed them over to Clara Barton who ensured the graves would be marked and the families of the victims informed. [5] The rare books collection of the ICRC Library comprises a copy of these lists, signed by Clara Barton herself and addressed to ICRC founders Louis Appia and Gustave Moynier. In 1869, she submitted the text of a resolution to the Senate, asking for families of missing soldiers to be compensated like the families of the deceased. Clara Barton’s understanding of the needs of the communities affected by the conflict makes her a true pioneer of the work of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, long before she became its official ambassador overseas. Her action for the missing and their loved ones bears great similarities with that of the ICRC’s Central Tracing Agency. Founded in 1870, the Agency is still active to this day, working to trace the missing and reunite the families separated by armed conflicts.

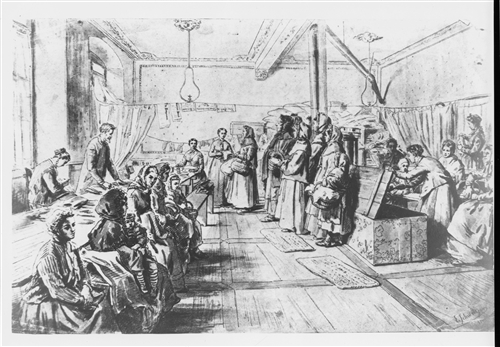

When her activities for war victims came to a halt, Clara Barton earned a living giving lectures across the country. Surfing on her national fame, she became one of the most successful professional public speakers of the period. This activity took a definite toll on her health, which encouraged her to leave for a trip to Europe. In Switzerland, she met Dr. Louis Appia, one of the founding members of the International Committee of the Red Cross. In 1870, the Franco-Prussian war became the first conflict to mobilize the newly founded National Societies of the Red Cross. Clara Barton interrupted her trip and joined without hesitation the ranks of the volunteers who tended to the wounded on the battlefields. Sent to Strasbourg to help the inhabitants of the besieged city, she focused on helping the local population become self-supporting rather than creating dependency on external help, thus displaying a visionary awareness of the long-term effects of her action.

«Treaty ratified today »

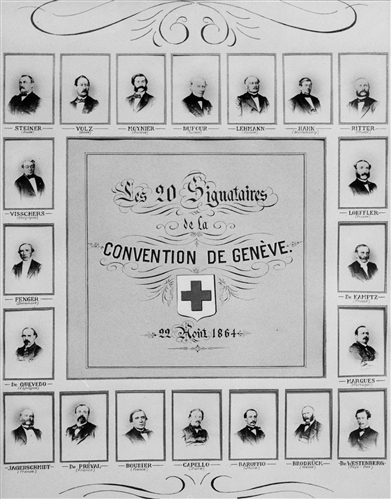

Clara Barton returned home convinced of the importance of the work of the National Societies of the Red Cross both in peace and war time. She resolved to secure the American ratification of the 1864 Geneva Convention, the first body of international law to give protection to wounded and sick soldiers and those tending to them. Becoming the ICRC’s official representative in the United States, she worked to convince government officials suspicious of international agreements of the importance of the Convention. She kept ICRC President Gustave Moynier updated on the progress of her work. In a letter discussed during the Committee’s February 2nd 1878 assembly, she gives “highly interesting details on the many steps she’s taken to convince the American Government to sign the Geneva Convention and [that she is] hopeful that her efforts will eventually pay off, but [that] it will still take some time”. [6] Her patience will certainly be tested, but Clara Barton is not one easily deterred. On March 17th 1881 she writes Doctor Louis Appia: « (…) after all these years of willing, hoping, and waiting I want to give you and your noble society the first word of hope. The “Convention” is not signed, but I believe it will be, and that, soon. I have matters in such a course of training that I do not see how it can fail, nor how it can much longer delay, but I have been compelled to wait through almost an entire Administration of our Government to gain a hearing ». [7]

After successfully rallying President Garfield to her cause, she started a publicity campaign to make the principles of the Red Cross better known to the general public. In May 1881 she founded ‘The American Association of the Red Cross’ and officially became its president on June 9th of the same year. On March 17th 1882, Clara Barton could finally deliver the long awaited good news; Gustave Moynier received that morning a telegram bearing the words: ‘Treaty ratified today’. [8]

President of the American Association of the Red Cross (1881 – 1904)

When she founded the American Red Cross, importing an idea born on the battlefield to her now peaceful country, Clara Barton was fully aware that its action would need to be adapted to meet her compatriots’ needs, as the prospect of a future war in the U.S. seemed highly unlikely. She thus developed the activities of the newly created organization around disaster relief. During its first decade of activity, the American Red Cross notably provided assistance to the victims of the 1882 Michigan forest fires, of the 1885 Texas famine and of the flood that practically wiped the town of Johnston, Pennsylvania, off the map in 1889. In 1893 the Sea Islands off the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia were devastated by one of the deadliest hurricanes in American history. Despite Clara Barton’s best efforts, the government, in the midst of a recession, denied the victims any financial help. The American Red Cross was thus practically the sole actor to offer assistance to the victims. Clara Barton organized a major relief campaign that were to allow the thirty thousand inhabitants of the affected Islands to recover from the hurricane in less than a year. [9] During this period, the American Red Cross also took part in international relief efforts, sending food and relief packages to countries affected by famine or conflicts. It brought assistance to the Russian population in 1891, the Armenian population in 1896, and the Cuban population during the 1898 Spanish-American war.

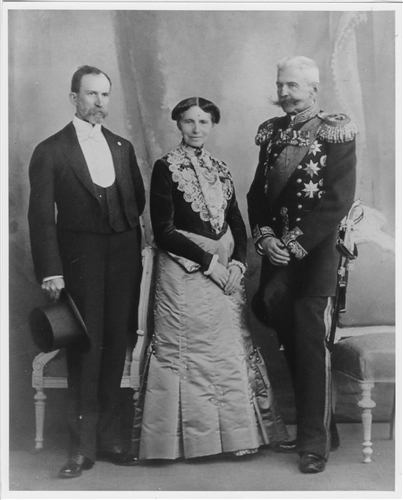

Clara Barton at the 7th International Conference of the Red Cross, with American delegate B. F. Tillingbast and Russian admiral N. Kazakoff (ICRC Archives, ARR)

In addition to conducting those large-scale relief campaigns, Clara Barton continued to be an active member of the Movement she successfully implemented in the United States. In 1902, she represented the American Red Cross during the 7th International Conference of the Red Cross. The discourse she gave in Saint Petersburg and her report about the Conference to the U.S. President were published together in a booklet. At over seventy years of age, Clara Barton was still assuming alone the presidency of the American Red Cross, an organization she had come to regard as truly her own. Inside its ranks, however, her management style and use of resources were highly criticized. If she certainly never used the organization’s funds for her personal benefit, it is nevertheless true that she did not truly separate her own finances and those of the Red Cross. This confusion allowed a group of dissidents to convince President Roosevelt to appoint a congressional committee to investigate her management. Even though the investigation remained fruitless, Clara Barton resigned from the Red Cross on May 14th 1904. Her departure in such difficult conditions from the organization she had built and led for twenty-three years would nevertheless not erase the importance of her legacy. Despite the political changes undertaken by Mabel Thorp Boardman’s new administration, the American Red Cross retained the direction Clara Barton had established and which gave the organization a continuing peacetime significance. Disaster relief still represents to this day a central part of its activities, as evidenced by its current motto ‘Help those affected by disasters’.

« I have lived much that I have not written, but I have written nothing that I have not lived » [10]

On top of her major contribution to humanitarian action, Clara Barton’s heritage also includes a large collection of writings and a prolific correspondence. She notably wrote multiple volumes on the history and activities of the American Red Cross Society, of which she would address signed copies to the Committee in Geneva. The ICRC Library’s rare books collection, which comprises publications collected by the organization’s founding members between 1862 and 1919, thus includes three of her publications : The history of the Red Cross : the treaty of Geneva and its adoption by the United States (1883), The Red Cross in Peace and War (1898), A story of the Red Cross: glimpses of field work (1904). The 1898 volume in particular, enriched with many photographs and illustrations, gives a comprehensive and well-constructed overview of the American Red Cross Society’s early days. Clara Barton first presents the International Movement of the Red Cross, the 1864 Diplomatic Conference and the first Geneva Convention, renamed for the occasion ‘The International Red Cross Treaty’. She also includes reproductions of her letters to the American Senate and Presidency in her book. Its core chapters describe the major relief actions carried out by her organization during its first years of activity.

A skilled communicator, Clara Barton soon understood the importance of promoting her action on the public scene and did not hesitate to use her personal fame for leverage. As has often been remarked, this desire to move the reader tended to influence the tone and content of her writings, with narratives of her activities sometimes appearing somewhat over-emphasized and sensationalized. [11] This tendency of hers seems to have led to a few disagreements with ICRC President Gustave Moynier. In 1890, the report of the Committee’s November 14th meeting mentions that he “had a rather heated exchange of letters with Miss Clara Barton about one of her publications which contained fanciful appreciations [and] Moynier had to point out important factual errors”. [13]

Clara Barton and her biographers

Clara Barton’s unique life story has certainly not failed to raise the interest of writers and historians across time. Not unlike her own writings, her biographies include more or less romanticized accounts of her action, depending on the time of writing and the author’s perspective. Three biographies praising her work and its legacy were published right in the years following her death : Corra Bacon-Foster’s Clara Barton humanitarian : from official records, letters and contemporary papers (1918), Charles Sumner Young Clara Barton : a centenary tribute to the world’s greatest humanitarian (1922), and The life of Clara Barton: founder of the American Red Cross (1922) by Clara Barton’s own nephew William E. Barton. At times quite sentimental, these first publications pay tribute to the action of a beloved figure of the period. In 1956, journalist and author Ishbel Ross dedicated a volume of her collection on eminent women to Clara Barton. The biography titled Angel of the battlefield: the life of Clara Barton relates the early years of the future founder of the American Red Cross, but also highlights the courage and determination shown in her tireless political activism. Ten years later, an edition of the portrait series ‘Illustrious Americans’ consecrates her as a heroine of national popular history. Published the same year, the volume Clara Barton and Dansville: together with supplementary materials focuses on her activities during the decade 1876-1886 and her efforts to secure the American ratification of the first Geneva Convention. Among the ‘supplementary materials’ included in the book the reader will find important excerpts of her correspondence with American officials and the ICRC founding members Gustave Moynier and Louis Appia.

In 1977 Clyde E. Buckingham published the comprehensive investigative biography Clara Barton: a broad humanity. He notably dedicates an interesting chapter of his study to her views on the social and political issues of her time, including women’s suffrage, equal pay and prison reform. This biography is also one of the first to address the controversies surrounding her management of the American Red Cross and to retrace in detail the history of her eviction. Finally, Clyde E. Buckingham underlines the way she developed highly innovative disaster relief policies, helping the long-term economic recovery of the affected populations as well as meeting their immediate needs. Samuel Willard Crompton’s 2009 publication Clara Barton: humanitarian selects and describes the defining moments of Clara Barton’s life, capturing the essence of her contribution to the history of humanitarian action. Departing from more traditional biographical or historical narratives, social history professor Marian Moser Jones published in 2013 the study The American Red Cross: from Clara Barton to the New Deal. Her work provides the reader with an in-depth analysis of the founding principles and methods of the organization from its creation to the 1930s, with a first part dedicated to the ‘Barton era’. Numerous studies have also been published on the history of the American Red Cross, including Patrick Gilbo’s volume The American Red Cross: The First Century (1981).

Despite their diverging approaches, the publications listed above all seem to agree on the importance of Clara Barton’s contribution to the history of humanitarian action. Way ahead of its time, her work was always characterized by an absolute respect for human dignity and a comprehensive, structured approach that took into account the long-term needs of beneficiaries. Driven by the conviction that assistance ought to be given based solely on need and not on the nationality, race, political or religious affiliations of the victims, Clara Barton’s lifetime humanitarian activity makes her a key figure of the development of the International Movement of the Red Cross. From spontaneous assistance on the battlefield to political activism at the top of the state and the organization of large-scale relief campaigns, her journey truly embodies the development of humanitarian aid in the end of the 19th and early 20th century.

[1] Clara Barton, A story of the Red Cross: glimpses of field work, 1904, p. 198.

[2] On August 31st 1862, Clara Barton opens with this statement a letter to her brother and sister. Read the rest of the letter and many other extracts of her correspondence on the website of the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum in Washington.

[3] Read the original letter in its entirety on the website of the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum.

[4] On March 10th 1886, the Senate, recognizing the work accomplished by Clara Barton’s inquiry service during its two years of activity, approved a resolution to repay her the sum of fifteen thousand dollars. (thirty-ninth Congress, Sess. I, Res. 11. Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations, of the United States of America, Vol. XIV, George P. Sanger (ed.), Boston : Little, Brown and Company, 1868).

[5] Marian Moser Jones, The American Red Cross: from Clara Barton to the New Deal, 2013, p. 17.

[6] Record of the Committee’s February 2nd 1878 meeting.

[7] A copy of this letter is kept in the ICRC Archives, under the reference ACICR, AF 5,1 65.

[8] The original telegram is kept in the ICRC Archives (ACICR, AF 5,1 95). This terse writing style, obviously dictated by the selected mode of communication, is quite out of character for Clara Barton, prolific – and talented, if sometimes overemphatic – writer. She will write Gustave Moynier a more official letter the next day, starting with the sentence “I have the gratifying privilege of confirming with my pen the intelligence which I trust has already reached you by telegraph, of the adhesion of the Government of the United States of America to the articles of the Convention of Geneva.” ACICR, AF 5,1 96.

[9] Clyde E. Buckingham, Clara Barton: a broad humanity, 1980, p. 233.

[10] Clara Barton, A story of the Red Cross: glimpses of field work, 1904, p. 1.

[11] Clyde E. Buckingham, Clara Barton: a broad humanity, 1980, 152.

[12] Record of the Committee’s November 14th 1890 meeting.

Thanks for the praise of my dad’s book, Clyde E. Buckingham Clara Barton A Broad Humanity. As historian and Research Analyst for Red cross in DC, he wrote many papers which I have and Ii have an unpublished manuscript on Red Cross Park which was planned for Bedford Indiana. I am looking for a home for these documents.

A lot of his research is located at the National Archives in college park, Maryland. But the online descriptions are very broad and I doubt many researchers would ever think to find valuable info there. I am wondering if you could suggest a repository for these items. I have already donated some to the Depauw University which he graduated from.

Mary Buckingham Lipsey

Dear Mary,

Many thanks for your kind comment on the article. Regarding the donation of your father’s papers and manuscript, have you tried reaching out to the archives of the American Red Cross ? You can contact them at the following e-mail adress: RedCrossHistory(at)usa.redcross.org.

Best regards,

Charlotte Mohr (ICRC Library)