When it first emerged at the end of the 1920s, audio commentary immediately became an invaluable companion to film imagery. Nevertheless, it was only years later that commentary was integrated as a truly complementary element, present first and foremost to enhance what appeared on screen. The evolution of audio commentary can be seen in various examples drawn from the film archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), examples that illustrate how commentary has in the end always reflected the times.

Sound in film

Categories of sound

Whether to create an ambience, make a thought more accessible or convey emotions, film sound is used to accompany the imagery and give the viewer an immersive experience where audio and visuals meld to form a unified whole. Before analysing in detail audio commentary and its evolution over several decades of ICRC films, it is worth discussing sound itself, focusing first on the types of sound that exist.

In the audiovisual world, sound can be divided into three categories:

- voice, including audio commentary

- music

- other noises or sound effects of any kind.

Voice includes all audible utterances on the screen, such as voice-overs (including audio commentary), voice-over translation (simultaneous translation of filmed remarks) and any other speech or singing.

Music, as one would expect, encompasses any melody performed with instruments, whether recorded during filming or added in post-production.

The final category includes all noises beyond voice and music. Such sounds are obtained in several ways:

- Sound is recorded during filming, either at the same time as the image or separately and then later synchronized.

- Background noises from a sound library are edited in.

- Sounds are created and recorded in a studio and then edited in.

Diegetic and extradiegetic sound

Although classifying various types of sound using the categories above is generally simple, sound can also be classified according to its origins in relationship to the narrative world of the film. A distinction is drawn between sound that comes from within the narrative, known as diegetic sound, and sound that is external to the narrative, known as extradiegetic sound:

“Diegetic sound is sound that has physical origins in the shots that make up a sequence. This includes dialogue on- and off-screen, so long as it is part of what is being filmed (including, for example, the sound of telephone calls received by characters) and anything that can be heard by the characters present in the sequence.” [1]

“Extradiegetic sound is sound that originates from outside the shots that make up the sequence in question. It includes any background music that is composed and recorded before or after filming and belongs to the film’s original soundtrack. In silent film, music performed at the base of the screen, sound effects and live narration made up what narratology today refers to as extradiegetic sound.” [2]

The history of sound

A prisoner of silence

Silent era : The period in cinematic history in which the majority of films had neither soundtracks nor synchronized sound. The silent era extended from the birth of cinema up to the years 1927 to 1930. Sound was often added to silent films live during screening, including music and sound effects. [3]

When the first films were made, it was impossible for sound to accompany the images projected onto the screen – at least, not properly speaking. Though they were working in the silent-film era, audiovisual professionals had no shortage of ideas for how to overcome the constraints of a medium incapable of emitting the slightest sound. When films were screened, one kind of sound did appear: live music. Music highlighted the images on the screen, as it would continue to do well beyond the emergence of sound film; the major difference was that the music was performed anew each night, making each screening unique.

Also during the silent era, a type of commentary first appeared: visual commentary. Title cards bearing one or more sentences were filmed in static shots for several seconds at a time. The film was thus enlivened by silent commentary, the era’s counterpart to voice-overs. But contrary to audio commentary – which may appear throughout a film without disrupting the fluidity of the visuals – title cards broke the rhythm of the narrative playing out each time they appeared. Too many, and the modern viewer’s experience of the film can quickly sour. For example, a 1923 film from the ICRC’s archives, “The International Red Cross Committee, Geneva, and its post-war activities” [4], contains eleven static shots of bilingual title cards. In a film of three minutes and forty seconds, more than half is dedicated to text, and only one minute and forty-five seconds to moving images.

Finally, for certain documentaries, a live narrator would introduce and comment on the films as they were projected to create an experience for viewers that was already approaching that of audio commentary in sound film. [5]

Please note that the vast majority of the following critiques regarding the quality of the films discussed are made after the fact and are not intended to represent the opinion of a contemporary viewer.

The road to sound films

Starting in the 1930s with the onset of the sound era, commentary underwent a revolution. Immediately, written commentary was replaced by more-practical audio commentary, marking the emergence of voice-overs.

Voice-over : Speech that does not come from the mouth of one of the people present in the scene – monologue or dialogue commenting on the action from an external point of view (i.e. narration). [6]

Voice-over commentary offered an entirely different dimension to film: viewers could receive an abundance of information – from the first frame to the last, if need be – with no interruption to the rhythm of the imagery.

Likewise, music also distinguished itself from other types of sound in film and rapidly became essential. As with voice-overs, music was recorded following filming, directly onto the soundtrack.

Yet it was still the beginning of the sound era, and, stylistically, many aspects of production had yet to be mastered. Recording sound on location was not yet possible, so sound editing was often imperfect. Music, voice and sound effects – all recorded outside of filming – were interwoven during editing, and sound quality varied depending on the source.

Not only was the sound quality sometimes wanting, but voice-over commentary could also quickly become redundant when paired with the film’s visuals. By audibly describing to viewers (often in a didactic tone) the images already visible on the screen in front of them, voice-over ultimately acted as a duplicate in many films. And, as is discussed later on, the high frequency with which voice-overs were generally used only accentuated the feeling of excess.

Portable sound

As with the appearance of sound film at the end of the 1920s, commentary would undergo yet another revolution in the 1960s. The weight and complexity of the first cameras required those being filmed to stay as still as possible. With time and major technological advances, this visual constraint gradually dissipated before finally disappearing altogether. Likewise, as sound equipment decreased in size in the 1960s, it became possible to record sound on location, which would also change the way documentaries were made. Once the voices of those being filmed could be recorded live, the entire process of filming was turned upside down. The director could now make use of filmed interviews for sharing information, emphasizing what interviewees said and considerably decreasing post-production work. Up to that point, voice-overs had enjoyed a dominant role in relation to interviewees by relating what they had to say to the viewer; now, the director could move among them, able to question them directly and allow them to speak for themselves.

It was also no longer necessary to explain everything through commentary because the images could literally speak for themselves. The nature of the audio work needed was redefined: the individuals on screen no longer required an intermediary between them and the audience – they could tell their own story through filmed interviews; instead of sound effects and other contrivances, ambient sound could be recorded on location and then reworked in post-production when necessary; even music could be recorded at the time of filming, supplanting what in the past would have been added during editing.

In addition, while the emergence of sound in the 1930s had enabled commentary to run throughout, the practice of recording sound on location starting in the 1960s would vastly cut back the time dedicated to such commentary – no more minutes-long monologues describing what viewers already saw before them. Now, commentary could withdraw and give the images space to breathe. The viewer no longer needed voice-overs to understand the situation because they could listen to people as they were interviewed on the spot. This evolution would also alter how films were produced in the years to come.

The evolution of audio commentary

Silence is broken

With the onset of the sound era, there was no lack of options for adding emphasis to films. However, the vast array of possibilities available in the editing room would have repercussions for many films’ overall quality. The use of multiple types of sound, all added in post-production, created an inconsistent soundtrack. In addition to less-than-perfect sound effects, such as for explosions, audio commentary also presented an imbalance. And unlike images, which with time gain documentary value, commentary only continues to age, without any added value. Edited and paired with visuals, such soundtracks often fail to convince today’s viewers of the quality of the audiovisual work and sometimes even detract from the films’ immersive quality.

Commentary also depended on what the images presented. Although their relationship had to be complementary to work as well as possible, they too often tended to compete. Indeed, they shared almost identical content, and as synchronously as possible. Thus, the viewer often had to process the same information from two different channels, one visual and one aural, inevitably leading to redundancy. In the clip below from the 1960 film “Operation Congo” [7], the issue is exacerbated when the commentary, initially synchronized, becomes uncoupled from the images. The narrator speaks of laundry hung overhead, endless queues, first-responders ready to come to aid – all with several seconds’ delay from the corresponding visuals. At the end, the audio and the visuals converge once more as mothers and children appear on screen.

“Operation Congo” / © ICRC, Swiss Red Cross / G. Kuhne, P. Molteni, R. Bech / 1960 / V-F-CR-H-00114.

Because the images also remain largely dependent on the commentary, what viewers see on the screen and what the film is intended to communicate sometimes diverge. This includes, for example, humanitarian propaganda films in which the appearance of the “hero” must impress at least as much as his actions on the ground. Indeed, some directorial choices may read today as being in poor taste.

In “That they may live again” (1948) [8], viewers could be confused by the tone used to introduce the Second World War and the devastation it left behind in countless countries. The voice-over sounds cheerful and mounts in intensity as the film spectacularly displays the various countries that were bombed in the war. The name of each country is displayed in large print, set to the rhythm of explosions going off in devastated cities. Later on, amid the ruins, a little girl stands next to her mother, who is sick with tuberculosis. As the commentator wonders aloud what the future has in store for the girl if her mother were to die, the teary-eyed girl looks furtively into the camera. And just then, relief workers are shown arriving with great pomp, set to triumphant music and with the red cross emblem fluttering in the background.

A similar introduction appears in “… Blood is still being shed!” [9] from 1958. The arrival of an ICRC delegate coming to visit thousands of prisoners is set to a jovial tune that contrasts starkly with the tense situation depicted up to that point.

“… Blood is still being shed!” / © ICRC / C.-G. Duvanel / 1958 / V-F-CR-H-00047.

Another limitation of the commentary of the era relates to the tone of superiority voice-overs assumed in relation to the victims portrayed. The film “Homeless in Palestine: Aspects of a relief action” [10], produced in 1950, “conforms with contemporary codes as regards its commentary, which today may seem antiquated owing to its paternalistic, even colonialist, quality”. [11] For example, the film presents Arab mothers as having been ignorant of basic aspects of childcare prior to contact with ICRC staff.

In the 1961 film “Action Népal” [12], the commentary also takes on a tone that one might deem superior – to the point of infantilizing the women being filmed. The narrator vaunts the merits of “thoroughly washing, in the Swiss manner”, [13] and remarks that it is “possible to pretty oneself up even without a permanent wave”. [14] In addition, although Nepalis “are very different to us Europeans … they deserve our sympathy and should be rescued from their misfortune”. [15] In spite of this, the film ends on a much truer and more pertinent note – the narrator remarks that while “their behaviour may strike us as strange … our way of life, our artificial agitation, our modern customs and our love of technology must strike them as equally astonishing”. [16]

Finally, in the era before the spread of synchronous sound, most films portrayed both victims and delegates impersonally. This was due in part to the technical limitations of the era. Because direct recording of sound was not yet possible, the people being filmed only rarely had their say. Without interviews or other filmed accounts, they depended on audio commentary to make their stories known, at the risk of having their screen time reduced to the bare minimum.

The voices of the forgotten

Starting in the early 1960s, technical advances in sound recording turned audio commentary upside down. Up to that point, it had enjoyed a dominant position over silent visuals; now, it was put to the service of images that spoke for themselves. One result was that commentary would feature in films less frequently.

In “SOS Congo” (1960) [17], an interview with sound recorded on location presages the changes looming for audio commentary. Up to that point, commentary would usually report on what was being said by those visible on screen. But now speech could be recorded on location and then synchronized in post-production with the images filmed the same day, rendering commentary obsolete in many sequences. And, naturally, the time allotted for commentary shrank to the bare minimum, though in some cases it took the form of voice-over translation of a foreign language.

“SOS Congo” / © ICRC, Swiss Red Cross / G. Kuhne, P. Molteni, R. Bech / 1960 / V-F-CR-H-00115.

While the civilians, soldiers, delegates and others portrayed in most earlier films were afforded little individuality, a shift towards greater realism began when those being depicted could speak for themselves. When filming, directors no longer hesitated to record civilians directly affected by conflict in their village, or experts in a particularly technical matter up for discussion. Just as with audio commentary, such individuals were given greater prominence, owing to their often-deeper understanding of the topic at hand. But contrary to a typical voice-over, their words were unscripted. Moreover, voices could now be directly associated with the people being filmed, unlike anonymous commentary only reporting on what others had said. The 1969 film “Nigeria two years after” [18] sets out the various activities carried out in Nigeria by giving the floor to ICRC experts from the field. The tracing agency official, the inventory controller, the head mechanic and the refugee camp supervisor each explain directly to viewers what they do to help the surrounding community. In addition to providing precise information on their work, this approach also gives a voice to humanitarians in the field.

Finally, the ICRC’s films had displayed cinematic ambitions since the 1920s. More-flexible commentary naturally paved the way for more-ambitious directing. Many films in the 1980s shifted from traditional voice-overs towards narration with greater interiority. However, this took an almost paradoxical turn: On the level of substance, such methods accentuated the realist aspect of documentary. But stylistically they emphasized its fictional quality. This choice was nevertheless made consciously and willingly by the directors of films such as “Letter from Lebanon” (1984) [19], “A strategy for salvation” (1985) [20] and “The story of Omer Khan” (1988) [21]. In each film, the narrator shares serious reflections without even necessarily being visible. Traditional voice-overs thus turned into something more understated to make space for an interior voice as fascinating as it is personal. In the clip below, the boy Omer not only shares his doubts and fears but gives more significance to the faces of the injured and the loved ones at their sides by pausing after each of the meaningful questions he poses.

“The story of Omer Khan” / © ICRC / E. Winiger / 1988 / V-F-CR-H-00169.

Two films, two eras

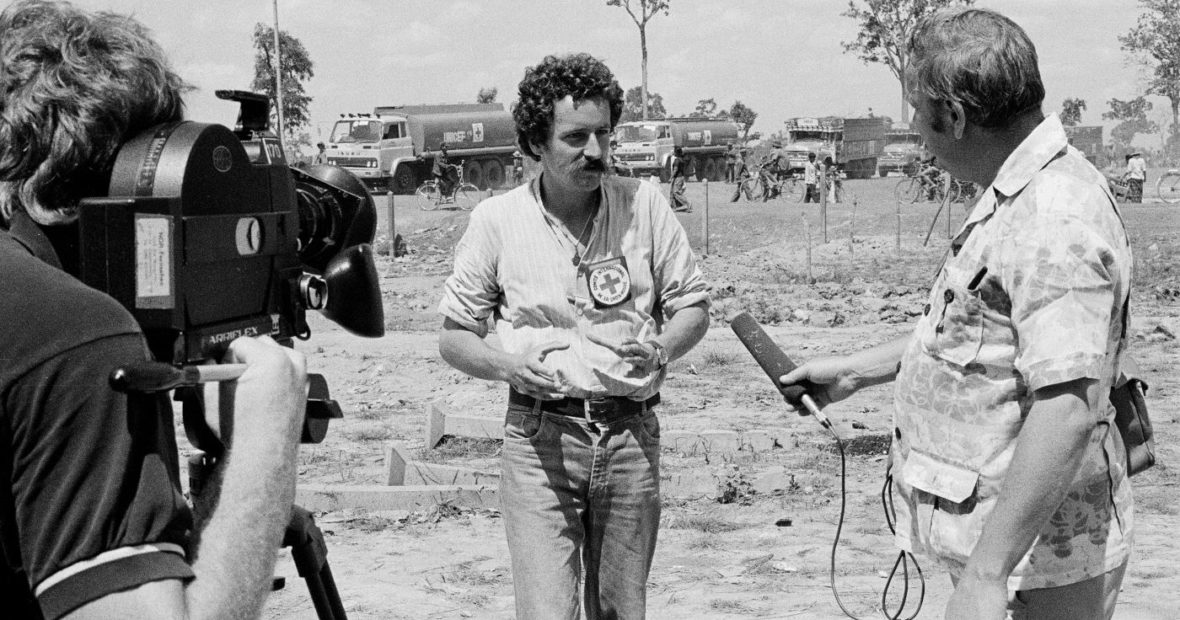

Two films produced in two different eras illustrate the evolution of audio commentary in terms of both style and substance. “SOS Congo” [22] was made in 1960, when live sound recording had just begun to spread. The film displays many of the previously discussed limitations of the time period, but it also showcases more-modern directorial choices that can be found in later productions, such as “A question of relief” (1980) [23]. The latter, which was shot in Cambodia and Thailand in 1979, portrays the difficulties encountered by Cambodians through directing that is so spare as to be stripped of all superfluity. The emphasis is placed on the civilians and their suffering, but also on the work of ICRC delegates. When audio commentary is needed, it is understated, allowing the images speak for themselves.

In “SOS Congo”, what perhaps strikes the viewer most initially is the frequently relaxed tone of the voice-over, in stark contrast to the film’s subject matter. In 1960, the then–Republic of the Congo had just declared its independence and the country was in the grips of turmoil that would last for more than five years. The same year, the ICRC carried out health aid on an unprecedented scale and in particularly difficult conditions. [24] Georges Kuhne, the famous Swiss radio and television presenter, narrates the French version of the documentary; [25] be it Kuhne’s pronunciation, the vocabulary used or the seeming irrelevance of some of his remarks, the commentary operates by principles that might surprise more than one viewer today.

“SOS Congo” / © ICRC, Swiss Red Cross / G. Kuhne, P. Molteni, R. Bech / 1960 / V-F-CR-H-00115.

This contrasts tellingly with “A question of relief”, which was produced twenty years later. Not only does the commentary leave room for the voices of Cambodian civilians directly affected by the conflict in the country, but it remains sober and never diverges from the imagery in a way that could be misinterpreted. Aided significantly by directing that harmonizes with the imagery, the documentary aims to achieve greater realism by staying close to the victims and humanitarians being filmed. For example, a refugee in need of help first tells his story. Then, more people are shown awaiting aid, without explicit explanation of why it is overdue. Ultimately, the viewer is led to understand that the aid has arrived via images of civilians carrying bags of food, but the commentary never directly says as much.

“A question of relief” / © ICRC, Derek Hart Productions / D. Hart / 1980 / V-F-CR-H-00147.

As previously mentioned, commentary and imagery at times compete. This conflict manifests itself in various ways in the first two minutes of “SOS Congo”, as the viewer is introduced to a country being eaten away from the inside by conflict. First, information is continuously presented to the viewer in two different streams simultaneously, one seen and one heard. The audio and visuals also struggle to keep in sync, and a lag swiftly develops between the two. The voice-over then pauses and does not continue until the images have caught up. What is more, the commentary fails to mention the evacuations of European nationals by plane – a significant moment in the crisis rocking the country – even when they are shown on the screen. Every action shown on screen is eligible for mention, making this is a surprising omission.

“SOS Congo” / © ICRC, Swiss Red Cross / G. Kuhne, P. Molteni, R. Bech / 1960 / V-F-CR-H-00115.

In addition, contrary to what one might expect, “A question of relief” dedicates roughly the same length of time to commentary as does “SOS Congo”, but the former does so much more efficiently. When present, the voice-over acts as accompaniment to the images in order to reinforce what they show, for example by offering additional information on a historical event. And when the voice-over pauses, it is always by choice rather than necessity, whether to allow a child’s cries to be heard or to give way to the melody that comes back to haunt the viewer throughout the film.

“A question of relief” / © ICRC, Derek Hart Productions / D. Hart / 1980 / V-F-CR-H-00147.

Nevertheless, “SOS Congo” contains directorial choices more in line with what one sees later on, including in films such as “A question of relief”.

First among them is the use of sound recorded on location during filming, shifting the role of the audio commentary. In addition to the previously mentioned interview with the future Congolese doctor, the voice-over directly addresses the location sound by discussing the meaning of the songs that had been recorded during filming. [26]

The final minute of the film also offers an excellent example of commentary serving as a true complement to the visuals. As a man badly injured in a road accident is shown being carried off on a stretcher, the voice-over provides a conclusion to his story, if a bitter one: “This man … will be dead before reaching the operating theatre.” [27] It is simple and effective. Likewise, the voice-over pauses as a Congolese woman gives birth to her first child, and her pain is juxtaposed with that of her country. To accompany her labour, the voice-over gives way to music, then re-emerges a few seconds later to close on a positive note: “But the child is born, and its arrival deserves a smile, and hope.” [28]

Final thoughts

“SOS Congo” and “A question of relief” are above all films that remain faithful to the norms and constraints of their respective eras. More generally, be it the transition from silent film to sound film, or that from the initial appearance of commentary to sound recording on location, the ICRC’s films have evolved at a pace with technological innovation. It is also due to these advances that commentary has moved from potentially overshadowing the visuals to acting as a truly complementary element used to accompany and above all enrich what is shown on the screen. But with the gift of hindsight, while images continue to hold documentary value, one may rightly wonder about the absence of real added value in the audio commentary accompanying them.

Translation from French to English by Heather Thompson.

[1] “Son diégétique et extradiégétique”, Wikipedia: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Son_diégétique_et_extradiégétique (all sources accessed 30 November 2021). Translated.

[2] Ibid.

[3] V. Pinel, Vocabulaire Technique du Cinéma, Nathan Université, Paris, 1996: p. 262. Translated.

[4] “The International Red Cross Committee, Geneva, and its post-war activities”, director J. Brocher, V-F-CR-H-00013-A, ICRC, Geneva, 1923.

[5] E. Natale, “Quand l’humanitaire commençait à faire son cinéma: Les films du CICR des années 20”, International Review of the Red Cross, No. 854, June 2004, p. 431.

[6] Pinel, p. 435. Translated.

[7] “Operation Congo”, director G. Kuhne, V-F-CR-H-00114, ICRC / Swiss Red Cross, Geneva, 1960.

[8] “That they may live again”, director C. von Barany, V-F-CR-H-00004, ICRC, Geneva, 1948.

[9] “… Blood is still being shed!”, director C.-G. Duvanel, V-F-CR-H-00047, ICRC, Geneva, 1958.

[10] “Homeless in Palestine: Aspects of a relief action”, director C.-G. Duvanel, V-F-CR-H-00049, ICRC, Geneva, 1950.

[11] S. Crenn, “Les errants de Palestine”, ICRC, Geneva, 2015.

[12] “Action Népal”, director J. Baer, V-F-CR-H-00140, ICRC, Geneva, 1961.

[13] Idem, 00:07:29–00:07:32. Translated.

[14] Idem, 00:07:55–00:07:59. Translated.

[15] Idem, 00:03:53–00:04:02. Translated.

[16] Idem, 00:19:45–00:19:55. Translated.

[17] “SOS Congo”, directors G. Kuhne, P. Molteni and R. Bech, V-F-CR-H-00115, ICRC / Swiss Red Cross, Geneva, 1960.

[18] “Nigeria two years after”, director J. Santandrea, V-F-CR-H-00110, ICRC, 1969.

[19] “Letter from Lebanon”, director J. Ash, V-F-CR-H-00165, ICRC, Geneva, 1984.

For more information, see: P. Romagnoli, “You have mail: ‘Letter from Lebanon’, a film by John Ash (1)”, ICRC, Geneva, 2020.

[20] “A strategy for salvation”, director J.-D. Bloesch, V-F-CR-H-00139, ICRC, Geneva, 1985.

[21] “The story of Omer Khan”, director E. Winiger, V-F-CR-H-00169, ICRC, Geneva, 1988.

[22] See note 17.

[23] “A question of relief”, director D. Hart, V-F-CR-H-00147, ICRC / Derek Hart Productions, Geneva / London, 1980.

[24] ICRC, Annual Report 1960, ICRC, Geneva, 1961.

[25] “Georges Hardy”, Wikipedia: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Hardy.

[26] “SOS Congo”, 00:19:10–00:19:17.

[27] Idem, 00:22:03–00:22:08.

[28] Idem, 00:22:49–00:22:55.

Comments