The red cross emblem is much more than a mere logo. It is a symbol of such profound significance that the original relief organization founded by Henry Dunant, the International Committee for Relief to the Wounded, was renamed the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in 1875, to include the emblem in its name. Today, the red cross emblem is recognized worldwide and used to both protect relief workers and to indicate membership of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Nevertheless, the history of the emblem is steeped in controversy. Indeed, in 1989, during his term as director of the ICRC’s International Law Department, Yves Sandoz described the emblem as both the ICRC’s strength and its weakness [1]. Discussions held over the following two decades eventually led to the signing, in 2005, of the Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem (Protocol III), which aimed to resolve the thorny issue of the emblem and put an end to more than a century of debate.

The cross as a banner

At the root of the controversy is the red cross itself and its much-debated connotations. Although it was long argued that the emblem merely represented an inverted Swiss federal flag, it appears that the real story is somewhat more complicated. As François Bugnion points out, the conceptual starting point for the emblem was the white background, as white had been used since time immemorial to symbolize peace. In 1857, Lucien Baudens, a French military doctor, proposed the universal use of white to identify medical personnel on the battlefield. Until that point, armies had simply assigned whatever colour they wished to identify their medical personnel.

The red cross was introduced later to make the emblem more recognizable and to draw attention to the ground-breaking Geneva-based relief organization that would become the ICRC. The minutes of the meeting of the International Committee for Relief to the Wounded – the precursor of the ICRC – held in February 1863, stated that:

“Finally, a badge, uniform or armlet might usefully be adopted, so that the bearers of such distinctive and universally adopted insignia would be given due recognition”[2].

By October of the same year, the idea of a plain white armlet still dominated the debate and there was – as yet – no mention of adding a red cross. The emblem as we know it today first appeared in Article 8 of the Resolutions of the 1863 Geneva International Conference. The question remains: why a cross and not some other emblem?

Unfortunately, contemporary documents shed no definitive light on the reasons for that choice. No records survive of the debates that took place on the adoption of that particular distinctive emblem. However, François Bugnion maintains that the most likely advantage of the cross was that it was simple, easy to reproduce and was imbued with centuries of symbolism.

The previously-mentioned origin theory – namely that the emblem merely represented an inverted Swiss flag – fails to fully account for the fact that the original concept for the emblem revolved around the colour white or refute the religious connotations of the emblem, since the Swiss federal cross itself is a reference to Christianity [3].

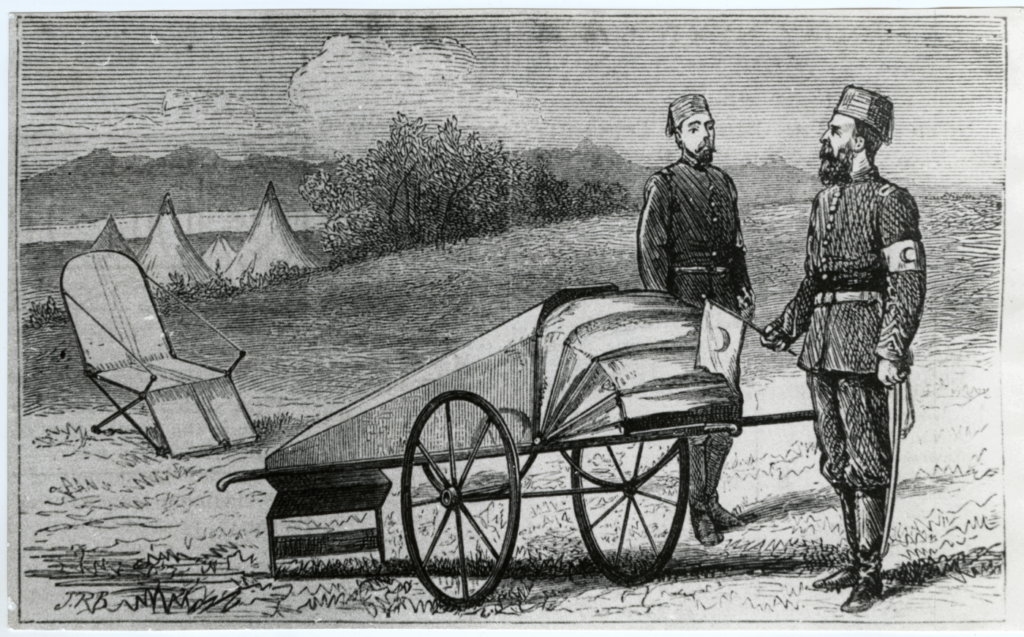

Nevertheless, during the first few years of the ICRC’s existence, the cross created no particular stumbling blocks for an essentially European institution. Things became more complicated when the ICRC, in its desire to achieve universality, reached out non-Christian nations, or rather when war broke out among them. The Ottoman Empire, a signatory to the 1864 Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field, announced during the conflict leading to the Russo-Turkish War (1875-1878) that it would use a red crescent instead of a red cross.

Emblem or logo?

The emblem essentially functions as:

- A protective device, the visible sign of the special protection afforded under international humanitarian law to certain categories of persons, equipment and vehicles. In order to fulfil this function, the emblem must be large enough to be clearly visible and must not have any additions, either on the emblem itself or the white background. This is what we call the emblem in its “pure” form.

- An indicative device, to indicate that a person or property has a connection with the Movement. It may feature additional information, such as the initials of the National Society, and should be relatively small in relation to the person or object it indicates.

These two different functions help to distinguish between the use of the red cross as an emblem and as a logo, with the former fulfilling a protective function and the latter used as a guide. It should be noted that the emblem per se does not confer protection. It is simply the visible sign of the protection afforded by the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols. For further information, please see the ICRC study on the use of the emblems.

Early challenges

In circular No. 36, which took note of this decision, the ICRC pointed out that this substitution “placed the Ottoman Society in an irregular position so far as its relations with the other Societies for relief to the wounded are concerned”. Moreover, it proposed a solution:

“It is up to the States signatory to the Geneva Convention to resolve the legal issue; we merely draw attention to the fact that that, in the note recently sent by the Swiss Federal Council to the Sublime Porte (the authorities of the Ottoman Empire) and in the opinion of most governments, the plan to replace the cross with a crescent on Ottoman ambulances would entail amending Article 7 of the Geneva Convention; in order for such a provision to become legally binding, States that have acceded to this Convention must express their consent in the form of a solemn international legislative act concluded and signed by representatives of those States”.

Although this solution could not be implemented in the short term as it required convening another diplomatic conference, the ICRC nevertheless endorsed, in the light of the ongoing conflict at that time, the founding of the Ottoman relief society and its use of an alternative emblem. During the war, Gustave Moynier also received a complaint from the Serbian side accusing Ottoman soldiers of having cut off the arm of a Red Cross worker because he had been wearing a white armlet bearing a red cross [4]. The use of the red crescent was therefore authorized, at least for the duration of the conflict. The emblem continued to be the subject of heated debate in subsequent decades, with the Persian relief society, in turn, adopting the red lion and sun as an alternative to the red cross. The 1906 Diplomatic Conference for the revision of the Geneva Convention of 1864 provided a universally acceptable provisional solution by reaffirming the use of a single distinctive emblem while tolerating the use of the red crescent and the red lion and sun.

This uncertain state of affairs lasted until 1929, when the diplomatic conference held that year finally recognized the red crescent and the red lion and sun as emblems of the Movement. During the conference, the delegations of Egypt, Turkey and Persia requested the addition of a subparagraph to Article 18 of the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field of 6 July 1906, authorizing the use of their respective emblems. During those discussions, the issue of what would later be referred to as the “risk of proliferation” was first raised by the representative of the United Kingdom:

“I would point out that if several different emblems are admitted there is likely to be a danger of confusion. If religious significance is attached to this sign it might happen that countries which have so far adopted the red cross will say: “It is not our religious emblem, we intend to change that by substituting another in its place”. I therefore believe that, from a practical point of view, there will be serious inconvenience”[5].

As a result, Article 19 of the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field, as amended in 1929, authorizes the use of a distinctive sign other than the red cross only for relief societies already using such signs. However, as Bugnion points out, this fundamentally flawed solution merely recognized the status quo without allowing other National Societies to opt for the crescent or the red lion and sun.

National Societies have not hesitated to blend the red cross with their own national symbols. Illustrations from the library’s collection of these organizations

Unresolved issues

These unresolved issues came to a head during preparations for the 1949 Diplomatic Conference for the establishment of international conventions for the protection of war victims, and at the event itself. Below are some of the key details relating to what were, at times, quite animated debates on the subject [6].

The flaws in the solution proposed in 1929 were already evident by 1935, when Afghanistan requested the recognition of a further exception and fourth emblem: the red arch. A few years later, the ICRC convened a conference of experts to consider the revision of the Geneva Convention. The conference, held in October 1937, proposed a return to a single distinctive emblem by deleting the paragraph of Article 19 of the 1929 Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field relating to the use of the red crescent and the red lion and sun.

“It would be extremely desirable to re-establish unity with regard to the emblem. (…) The red cross on a white background has no religious significance, as it represents the inverted heraldic colours of the Swiss federal flag, adopted as a tribute to Switzerland; given that the distinctive sign must in essence be international, there is no reason to substitute either religious symbols or national emblems for the red cross emblem”[7].

Nevertheless, given that the delegations of Turkey, Persia and Egypt did not attend the meeting, the conference of experts was unable to move forward and – in the end – the draft revised Convention retained the exceptions adopted by the diplomatic conference held in 1929.

As a result, the 17th International Conference of the Red Cross held in Stockholm in 1948, tasked with examining the draft revisions, decided not to delete the subparagraph in question for the time being. Nevertheless it expressed “the wish that the governments and National Societies concerned should endeavour to return as soon as possible to the unity of the Red Cross emblem”[8]. This was also the position of the ICRC: in a document addressed to the governments invited to the 1949 diplomatic conference, the ICRC recalled that at the preliminary conference of National Red Cross Societies held in 1946, several delegations had recommended that “suitable propaganda should be made in Near East countries, to explain the exact meaning of the Red Cross emblem”.

Noting that it was impractical to end the use of the red crescent in the short term, the above-mentioned document put forward several possible solutions, two of which would later be echoed in the provisions of Protocol III, adopted more than half a century later:

- The emblem of the red cross on a white ground might be employed in all countries. In certain exceptional cases, countries would have authority to add, in one corner of the flag, a particular symbol of small dimensions.

- The Geneva Convention might recognize, besides the red cross, one single exceptional and entirely new emblem, which would be employed by all the countries unable to adopt the red cross. Potential symbols included a red flame, red chevron or red square on a white background.

In the end, the diplomatic conference produced little in the way of tangible results, as Article 38 of the First Geneva Convention of 1949 repeated, word for word, Article 19 of the 1929 Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. An alternative solution put forward by the delegation from Burma (now Myanmar) was that each National Society should be free to use the emblem that suited it best, provided that it was always red on a white background. The delegation from the Netherlands, meanwhile, proposed that a completely new emblem should be designed to replace the symbols in use to date. Although each of the proposed solutions had its flaws, at least they had the merit of placing countries on an equal footing, which Article 38 had failed to do. In the end, the use of emblems other than the red cross continued to be reserved for countries that had already adopted such emblems and the diplomatic conference refused, for example, to authorize the use of the red shield of David (a hexagram, also known as the star of David) requested by the Israeli delegation.

Misuse of the red cross emblem

In addition to being the subject of controversy over its meaning, the emblem has also been misused. Illicit use of the emblem commonly covers:

- Perfidy: use of the emblem in conflict to protect combatants carrying out hostile acts.

- Usurpation: use of the emblem by unauthorized entities or persons, typically pharmacies or non-governmental organizations.

- Imitation: use of any sign that could potentially be confused with the emblem.

Because of the protective value of the emblem, the Movement has long focused on the problem of its improper use. In 2001, the Movement commissioned a study on the use of the emblems, the final version of which was published in 2009.

The path towards Protocol III

The issue of the shield of David would crop up repeatedly in subsequent decades. The diplomatic conference held in 1949 did not recognize the Magen David Adom relief society, established in 1930, because it used the red shield of David as an emblem. Almost a quarter of a century later, at the Diplomatic Conference on the reaffirmation and development of international humanitarian law applicable in armed conflicts (1974-1977), the Israeli delegation submitted an amendment to recognize the red shield of David as an official emblem; however, it subsequently withdrew the proposal as there was little prospect of a majority vote in its favour.

In the early 1990s, a further complication arose in connection with Article 38, namely the use of a dual emblem. Kazakhstan, which had recently gained independence, requested the use of both the red cross and the red crescent on a white background. However, all legal provisions adopted to date provided for the use of the red crescent instead of, rather than alongside, the red cross. In the end, rather than risk the ICRC refusing to recognize the National Society because of its emblem, the Kazakh Red Crescent Society opted to use the red crescent and joined the Movement in 2003. Similar problems arose for Eritrea. This was in spite of the fact that the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies had been using both emblems since 1983, to reflect its title.

Although the Islamic Republic of Iran had, in the meantime, abandoned the red lion and sun in favour of the red crescent, the Movement found itself on the threshold of the twenty-first century facing virtually the same obstacles as those over which it had stumbled almost half a century earlier. The fact that the red cross and red crescent remained the only recognized emblems of the Movement was sometimes perceived as bias in favour of Christians and Muslims. Although various alternative emblems were discussed, including the red palm (Syria), the red wheel (India), the red lamb (Zaire) and the red swastika (Sri Lanka), they were all ultimately rejected.

Geneva, Rath Museum. Inauguration of the exhibition “Humanizing war ? ICRC – 150 Years of Humanitarian Action.” (ICRC / Thierry Gassmann)

Worse still, perhaps, the main purpose of the emblem was called into question, as the neutrality that the symbols used by the Movement were designed to embody was being undermined by their association with the two dominant monotheistic religions. Intended to symbolize unity, the emblem appeared to have created rifts. Given the scale of the impasse, a thorough review of the use of the emblem, within the Movement and in international humanitarian law, was needed. The talks that began in the 1990s, following an appeal by ICRC president Cornelio Sommaruga, ultimately led to the signing in 2005 of Protocol III.

The provisions contained in Protocol III enshrine the use of the red crystal as the third emblem of the Movement, alongside the red cross and the red crescent. The crystal was chosen because of its generally positive associations (including with water) and simple design. The ICRC, with the help of the Swiss armed forces, even carried out visibility tests to ensure that the new emblem had the same protective capabilities as the cross and crescent.

Finally, Protocol III also stipulates that National Societies using the crystal may incorporate within it another emblem, provided that this decision has been communicated to the other High Contracting Parties. These National Societies may, therefore, use the designation of that emblem and display it within their national territory.

To our research guide on the 2005 Additional Protocol

Further reading

ICRC, Study on the use of the emblems : operational and commercial and non-operational issues, ICRC, Geneva, 2011.

François Bugnion, The emblem of the Red Cross: a brief history, ICRC, Geneva, 1977.

François Bugnion, “The red cross and red crescent emblems”, International Review of the Red Cross, Issue 272, September-October 1989, pp. 408-419.

Derya Üregen, Le Croissant-Rouge, outil de modernisation ou reflet d’un empire à la dérive? : des débuts difficiles aux guerres balkaniques 1868-1913,Master’s thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Fribourg, 2010.

Gerrit Jan Pulles, Crystallising an emblem : on the adoption of the third Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, Yearbook of international humanitarian law, Vol. 8, 2005, p. 296-319.

Issue 272 (October 1989) of the International Review of the Red Cross is devoted to the matter of the emblem.

There are also documents in our catalogue that address the question of the emblem.

Moreover, the ICRC’s audiovisual archives archives have several films on the issue. These include:

- The Emblem archive pack, illustrating the different uses of the emblem in different countries during different periods.

- The three emblems of humanity, an interview with François Bugnion, historian and member of the ICRC Assembly since May 2010.

- A short film, featuring archival footage, mainly not from the ICRC, on the theme of respect for the emblem.

[1] Yves Sandoz,“The red cross and red crescent emblems : what is at stake”, International Review of the Red Cross, Issue 272, September-October 1989, pp. 405-407.

[2] Procès-verbaux des séances du Comité international de la Croix -Rouge : 17 février 1863 – 28 août 1914

[3] Article (available only in French) on the « federal cross » in the Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (Historical Dictionary of Switzerland).

[4] Derya Üregen Le Croissant-Rouge, outil de modernisation ou reflet d’un empire à la dérive ? : des débuts difficiles aux guerres balkaniques 1868-1913, MA thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Fribourg, 2010, p. 53.

[5] ICRC, Actes de la conférence diplomatique convoquée par le Conseil fédéral suisse pour la révision de la Convention du 6 juillet 1906 pour l’amélioration du sort des blessés et malades dans les armées en campagne et pour l’élaboration d’une convention relative au traitement des prisonniers de guerre et réunie à Genève du 1er au 27 juillet 1929 , ICRC, Imprimerie H. Jarry, Geneva, 1906, p. 250.

[6] François Bugnion’s short book L’emblème de la Croix-Rouge : aperçu historique provides a comprehensive overview of the history of the emblem. See the “further reading” section at the end of this article.

[7] ICRC, Projet de revision de la Convention de Genève du 27 juillet 1929, ICRC, Geneva, 1937, p. 13.

[8] ICRC, Révision de la Convention de Genève du 27 Juillet 1929 pour l’amélioration du sort des blessés et des malades dans les armées en campagne, ICRC, Geneva, 1948, in a footnote to Article 31.

Comments