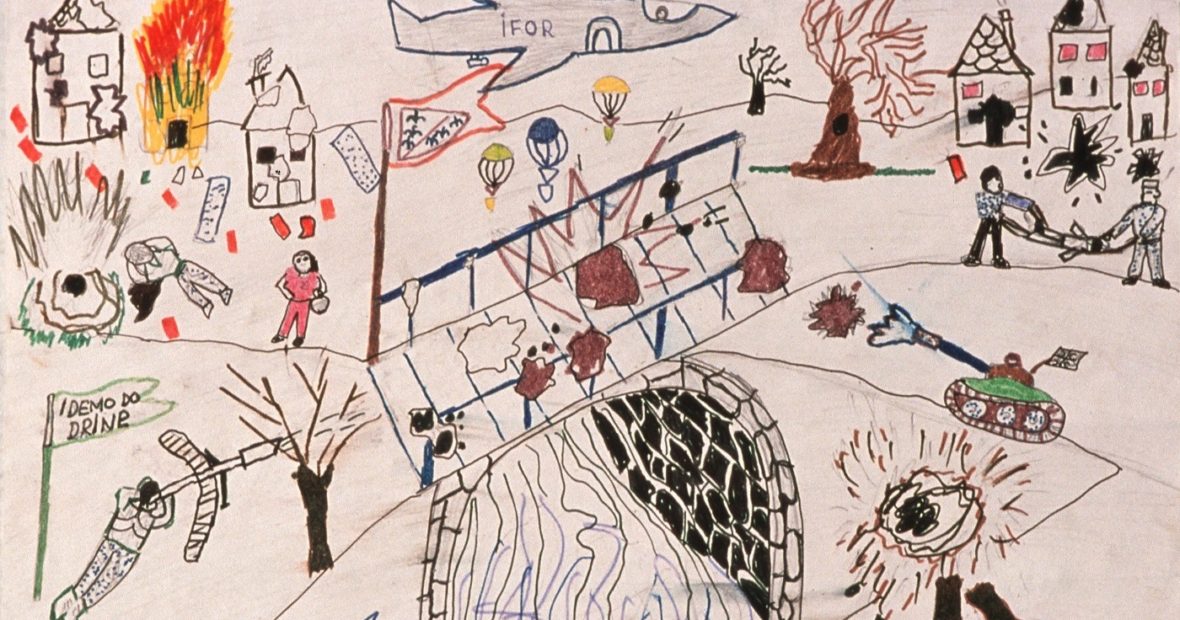

Save the Children reports that 420 million children live in conflict-affected areas, including those where a formal peace accord has been signed but tensions continue. Children in these ‘post-accord generations’ are raised and educated against the backdrop of protracted conflict, yet also during the transition to peace. In Northern Ireland, Kosovo, and the Republic of North Macedonia (RNM), the primary conflict-related groups have remained largely segregated even after the signing of peace agreements. All three sites have divided education systems in which children attend school based on their group background: in Northern Ireland, Protestant or Catholic; in Kosovo, Albanian or Serbian; and in RNM, Macedonian or Albanian. These children, while born after the respective peace accords, are nonetheless raised in the shadow of conflict.

These are the societies divided by protracted conflict in which the Helping Kids! lab works, studying how majority and minority children in separate education systems develop an understanding about conflict-related groups, and the implications of that awareness on intergroup prosocial behaviour. We argue that sharing across group lines can be a powerful antecedent of later peacebuilding in children.

Prejudice: a learned behaviour

To frame our research, we used the Social Identity Development Theory (SIDT) , which outlines children’s identity development with four (potential) phases: undifferentiated, awareness, preferences, and prejudice. The shift between these phases is shaped and informed by social contexts, such as school, family, and neighbourhood. This phase of our research focused on the development of awareness of conflict-related groups and its potential effect on children’s resource distribution in post-accord societies.

Our trained experimenters played child-friendly games on a laptop or tablet in primary schools in each setting, with participants evenly split by gender and background. These games asked children about their awareness of and preference for images, symbols, and names connected to the primary conflict-related groups in each site. Children were asked to drag and drop images into boxes randomly labelled with the conflict-related group backgrounds, i.e. in Northern Ireland, either Protestant/British or Catholic/Irish; in Kosovo, Albanian or Serbian; in RNM, Macedonian or Albanian. These images were paired, one in each hypothesized to be from each background, and represented a variety of contexts, including religious, political, cultural, and geographic symbols. The games also assessed children’s contact with, attitudes about, and sharing with ‘outgroup’ children, those who, in sociological terms, do not seem to belong to a specific ‘ingroup’.

Across all three settings, children were aware of the symbols associated with the respective conflict-related groups. For example, in Northern Ireland, children identified poppies as British and shamrocks as Irish; in Kosovo, children consistently categorized which murals and pop artists were Albanian or Serbian; and in the RNM, children distinguished celebratory foods as either Macedonian or Albanian.

Children’s ability to sort both ingroup and outgroup symbols increased with age. For example, in Kosovo, children could categorize a church, a street sign for Gracanica, and the Serbian national football jersey as Serbian, rather than Albanian, as early as six years old. Out of 26 images, children could associate 20 with their respective ethnic group by age seven and all images by age ten. In the RNM, children were asked to sort 32 images; children sorted eight symbols correctly at age six, two-thirds at age eight, and all by age ten.

Children with higher awareness of conflict-related group markers also expressed greater preference for ingroup symbols. These findings support the link between ethnic awareness and ethnic preference outlined by SIDT. Furthermore, children who preferred ingroup symbols shared fewer resources (i.e. stickers) with outgroup children. This finding suggests that the SIDT link between preference and prejudice may also be seen. Yet, positive experiences with and attitudes about outgroup children related to sharing more resources with outgroup children. Therefore, the study identifies factors which can both depress and enhance children’s intergroup giving.

Teaching peace: the sooner, the better

While there are similarities across all sites, we also found patterns unique to each context. In Northern Ireland, for example, national labels such as ‘British’ or ‘Irish’ tend to emerge earlier (ages 5-8) than ethno-political labels such as ‘Protestant’ or ‘Catholic’ (ages 9-11). For example, while younger children sorted curb paintings and bunting only with national labels, older children sorted these images with both types of labels above chance.

In Kosovo, single versus dual identities were explored. For example, children were asked if they preferred their own ethnic flag (Albanian or Serbian) or the Kosovo flag. Children from both groups showed a higher preference for their own ethnic flag (68%) over the Kosovo flag (32%). Preference of an ingroup flag over the Kosovo flag was linked with greater desired social distance between the two ethnic groups. The divided education system may play a role in these preferences, as divided schools with minimal or no opportunities for intergroup contact feed ethnic polarizations among children from a young age. Separation of schools and classes by ethnicity in Kosovo became the norm in the 1990s, but children are less able to develop a sense of tolerance if they lack the ability to engage with other kids from different backgrounds.

Yet, when shown a picture that included an Albanian or Serbian flag flying alongside the Kosovo flag, 48% of children preferred the integrated flags as opposed to their ingroup flag alone. This finding suggests that children prefer symbols conveying dual identities (ethnic and national together), compared to those where they have to choose either ethnic or national identity.

In the RNM, patterns across majority (Macedonian) and minority (Albanian) ethnic groups were explored. For example, politicians recently constructed a statue associated with Macedonian identity in the main square in Skopje. Macedonian children categorized the square as ‘Macedonian,’ but Albanian children did not, suggesting that Macedonian children have heard that the statue, and thus the square, represent their identity, whereas Albanian children still consider the square a public gathering space. Overall, Albanian children recognized Macedonian symbols related to tradition and everyday life (i.e. sports and culture) better than Macedonian children recognized the equivalent Albanian symbols. This result could be a consequence of Albanians’ position as a national minority and possibly needing to attend to the characteristics of the majority. Thus, while both Macedonian and Albanian children recognized outgroup symbols, national majority/minority status affected children’s awareness of outgroup symbols in everyday life.

***

Overall, our findings from Northern Ireland, Kosovo, and the RNM show the effects of conflict on children in a post-accord generation. Long-term peacebuilding must, therefore, start early. Fostering more positive outgroup attitudes and opportunities for outgroup contact may have promising implications for more constructive intergroup relations. Through conversations with families, school teachers and administrators, non-governmental organizations, and government officials, we hope our findings can inform public policies that help children living in conflict-affected areas around the world. Working on these antecedents of children’s peacebuilding, particularly through peacebuilding interventions in schools, can help lead, eventually, to more cohesive societies.

See also

- Filipa Schmitz Guinote, Three reasons why education needs the support of humanitarian actors in conflict zones, December 12, 2019

- Ellen Policinski, Children and war: upcoming Review edition, November 19, 2019

- Ezequiel Heffes & Carolin Nehmé, Ten armed groups share their views on education in armed conflict, May 2, 2018

In the past, the ICRC developed a very interesting tool supporting humanitarian education for children, base d on empathy. It was called “Exploring Humanitarian Law (EHL)” and a shorter version allowed teachers facilitating this programme in 5 modules of 1-2 hours each: https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/4100-mini-ehl-essence-humanitarian-law While this programme has been halted for a few years, I wish the ICRC considers reopening it, especially in view of recent worrying findings on acceptance for illegal practices, such as torture, amongst millenials: https://www.icrc.org/en/millennials-on-war

Excellent points, thanks for connecting the dots, Etienne!