Five States Parties to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention have recently submitted instruments of withdrawal, citing national security and military necessity, while at least one other has taken steps to “suspend” the Convention. These developments raise important questions about whether anti-personnel mines retain any meaningful military utility in contemporary conflict.

In this post, Erik Tollefsen, Head of the ICRC Weapon Contamination Unit and Pete Evans, Head of the ICRC Unit for Arms Carriers and Prevention examine this question from an operational perspective. They argue that advances in technology and the realities of modern warfare have significantly reduced the military relevance of anti-personnel mines, while their humanitarian consequences remain severe. They outline why some of the most frequently cited justifications – border security, the supposed benefits of “smart” mines, or perceived low cost – no longer withstand scrutiny, and why renewed interest in these weapons risks reversing decades of progress. The authors call on states to base decisions on rigorous, transparent assessments of current military relevance weighed against humanitarian and legal obligations. In a security environment defined by rapid innovation, they conclude that, now as at the Convention’s adoption 30 years ago, anti-personnel mines have no place on the modern battlefield – and that reaffirming the norm against their use is more urgent than ever.

The recent decision by several states to reconsider their commitments to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (APMBC) has reignited debate over the role of anti-personnel mines in modern warfare. It is a reckoning that dates back thirty years, when states negotiated the Convention and ultimately chose to prohibit these horrific weapons with the APMBC – with more than 80 percent of the world’s nations joining the treaty.

Yet the discussion resurfaces again today, against a stark humanitarian backdrop: casualties from mines and explosive remnants of war rose by 22 per cent between 2022 and 2023, with civilians accounting for 84 per cent of recorded casualties where the status was known – and more than a third of them children.[1] Even leaving these grave consequences aside, the question demanding urgent scrutiny is whether these weapons still serve any meaningful military purpose.

Anti-personnel mines once played a tactical role in shaping battlefields, but the nature of conflict has changed. New operational realities, advances in technology, and the growing precision of modern warfare have left little space for static weapons whose indiscriminate effects endure long after fighting ends.

The origins of anti-personnel mines

Efforts to restrict the movement of opposing forces are as old as warfare itself. Armies have long used obstacles to channel attackers and strengthen defences. With the introduction of explosives, these measures evolved from ditches and stakes into explosive devices capable of injuring or killing combatants.

By the early twentieth century, three main categories of mines had emerged: naval mines to attack shipping; anti-vehicle mines for tanks and armoured vehicles; and anti-personnel mines – small explosive charges with sensitive fuses activated by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person. Unlike anti-vehicle mines, which target material, anti-personnel mines are designed to injure or kill individuals, with effects that often last long after the hostilities end. Some improvised explosive devices and certain anti-vehicle mines with highly sensitive, victim-activated mechanisms can function in the same way as anti-personnel mines when they can be triggered by a person.

By the late twentieth century, the humanitarian toll of anti-personnel mines had become impossible to ignore. A broad coalition of states responded by negotiating and adopting the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention,[2] driven by recognition of the inhumanity of these weapons, the advocacy of humanitarian actors who had witnessed their effects first hand, and the assessment that, already then, these weapons had very limited military utility. The Convention prohibits the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of anti-personnel mines and requires the destruction of existing stockpiles. Anti-vehicle mines were not included in this prohibition and remain regulated under Amended Protocol II to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) and the broader framework of international humanitarian law (IHL) – a distinction that matters, as debates often conflate these two categories.

Amid renewed discussions about the Convention, recent moves by some states to withdraw or “suspend” obligations highlight a tension between humanitarian considerations and claims of military utility. Given their well-documented humanitarian consequences, it is timely to examine whether these weapons retain any credible military relevance on the twenty-first century battlefield.

Historical military roles of anti-personnel mines

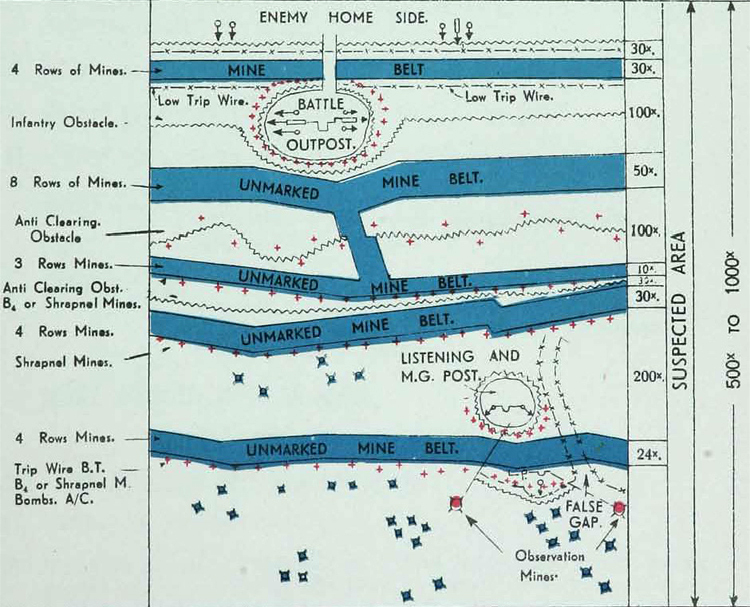

Historically, minefields were used to create or reinforce obstacles and influence the movement of opposing forces on the battlefield. Within that concept, anti-personnel mines were valued in several roles:

- Channelling and denying movement. In combination with anti-vehicle mines, anti-personnel mines were used to channel opposing forces into areas where they could be engaged by artillery or other weapons and to block access to key terrain. Minefields thus served as supporting measures that shaped, rather than decided, the outcome of engagements.

- Impeding breaching. Anti-personnel mines hindered the clearance of anti-vehicle minefields, preserving their effect and delaying breaching operations – a function that became increasingly relevant with mechanized warfare, as epitomized by both World Wars.

- Force protection. Anti-personnel mines secured vulnerable sectors or defensive perimeters, particularly around critical sites or where surveillance is difficult, allowing forces to redeploy elsewhere. They also protected infrastructure and detention facilities, deterring incursions or escapes.

However, deployment was resource-intensive and carried considerable risk of fratricide. Safe laying demanded specialist personnel, accurate mapping, and reliable marking and fencing. Between May 1967 and November 1971, 55 Australian soldiers were killed and some 250 wounded or maimed by M16 anti-personnel mines in the 11-km “barrier minefield” in Phuoc Tuy Province, southern Vietnam – a minefield laid and later lifted by Australian forces themselves. This single minefield accounted for around 10 per cent of all Australian casualties in the Vietnam War.

Contemporary relevance of anti-personnel mines

More than two decades since the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention entered into force, battlefield dynamics have rapidly evolved. Modern warfare – characterized by multi-domain operations, air-land manoeuvre, speed and precision – has transformed the conditions in which anti-personnel mines were once employed. Several developments now call into question whether these weapons retain any operational relevance:

- Alternative capabilities. Modern precision guided weapon systems, once limited to a few states, are now widely used to influence movement and restrict access to terrain. These systems can be repositioned or redirected as conditions change, achieving area-denial effects with flexibility that victim-activated devices cannot provide. In some contexts, natural or man-made obstacles are combined with remotely delivered supressing fires or uncrewed systems to achieve comparable area-denial effects, without the fixed nature and indiscriminate effects of anti-personnel mines.

- Persistent surveillance. Advances in sensors and networked systems, including airborne surveillance, ground-based radar, and drone technologies, have greatly reduced battlefield blind spots. These capabilities have diminished the tactical value of static area-denial weapons such as anti-personnel mines. When combined with precision strike systems, persistent surveillance allows forces to monitor and influence terrain dynamically, achieving area-control objectives without the lasting contamination risks inherent to minefields.

- Rapid breaching technologies. Modern clearance tools, such as explosive line charges, and remote mechanical clearance systems have reduced the time and risk of breaching. These capabilities weaken the traditional tactical value of anti-personnel mines in delaying an advance. Emerging technologies, including AI-enabled platforms capable of identifying and neutralizing mines using directional formed explosives or donor charges, are being tested in some contexts. While their deployment remains limited, and raises its own humanitarian and legal questions, these developments illustrate a shift in breaching tactics that further erodes any residual operational advantage offered by anti-personnel mines.

- Stagnant development. Anti-personnel mine design, including non-persistent types, has seen minimal innovation since the 1980s. By contrast, other military technologies have advanced rapidly in range, precision, and network integration. Even anti-vehicle mine systems have evolved. For instance, the PARM NextGen (DM 22) off-route anti-vehicle mine is designed for mobility and does not require to be protected by anti-personnel mine “keepers” due to the way it is deployed. This contrast underscores the redundancy of anti-personnel mines even in anti-vehicle mine operations.

Operational lessons from Ukraine

Recent analyses by the Russian Ministry of Defence and the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) covering the first 1,000 days of the international armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine provide no significant evidence that anti-personnel mines have delivered measurable military advantage. Instead, attention has focused on the rapid adaptation and integration of new weapons systems, some developed and fielded within weeks.

Where mine use is mentioned, reports rarely distinguish between anti-vehicle and anti-personnel mines. Anti-vehicle mines differ from anti-personnel mines in both design and activation. They are triggered by the movement or proximity of a vehicle, rather than by the presence, proximity or contact of a person. They remain regulated under IHL, including Amended Protocol II to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, and are not subject to the same categorical prohibition as anti-personnel mines.

A defining feature of this and other recent conflicts has been the widespread use of drones, which has reshaped battlefield planning and execution. Drones are now commonly employed for surveillance, target acquisition, and fire correction, and to deliver munitions against high-value or time-sensitive targets. They also operate as loitering munitions or one-way attack systems, and disrupt manoeuvre through their density, persistence and adaptability. Analyses of the conflict suggest that drones now account for a large proportion of vehicle losses and troop casualties in Ukraine.[3]

Beyond their tactical roles, the constant presence of drones has introduced new psychological pressures on those living or fighting under them.[4] As with anti-personnel mines in the past, when fear itself was considered a tactical effect, drones – often in combination with indirect fire – are reported to create a comparable sense of exposure and uncertainty on a broader and more continuous scale. This demonstrates that technological advances do not necessarily reduce human suffering but may simply alter its form. Understanding these evolving harms is essential to ensuring that new and emerging weapons and methods of warfare remain consistent with IHL.

The effectiveness of modern air-defence systems has reduced the utility of air manoeuvre and air delivery of fire support, leading combatants to rely more heavily on traditional artillery, as well as drone- and missile-delivered fire which effects are reported to have more impact on the battlefield than the use of landmines. In other contexts, troop mobility by helicopter or other platforms remains a form of manoeuvre against which anti-personnel mines offer no utility, while sensor and precision attack combinations are capable of countering it.

How contemporary warfare has rendered anti-personnel mines obsolete

The operational landscape of warfare has shifted so profoundly that the traditional roles once assigned to anti-personnel mines have little relevance today. As conflicts become faster, more interconnected, and more reliant on precision and sensing technologies, weapons that are static, in effect indiscriminate, and difficult to control no longer offer credible military advantage. Claims that mines remain necessary for border security, that “smart” or non-persistent variants reduce humanitarian harm, or that they provide a low-cost defensive option do not withstand scrutiny when examined against modern operational realities.

The following three sections explore some of the reasons why longstanding justifications for anti-personnel mine use have eroded: the limits of mines in border and terrain defence, the persistent unreliability of so-called “smart” mines, and the widening economic gap between mines and more adaptable contemporary systems.

Border security and terrain considerations

Some states have cited border security as a justification for the continued use of anti-personnel mines. Yet mines of all kinds are inherently inflexible and cannot adapt to changing movement patterns or evolving operational conditions. Their effectiveness is further limited in challenging terrain, such as marshlands, riverbanks, or areas prone to snow and flooding, where environmental conditions can cause drift, failure, or unintended contamination.

Recent experience with sensor-based systems – including in snowbound regions above the 60th parallel north – show that certain border-monitoring technologies can operate year-round and adapt to changing circumstances. Unlike anti-personnel mines, these approaches can serve broader purposes, such as detecting and responding to unauthorized border crossings or incursions, and may prompt a law enforcement response where appropriate.

In many contexts, the natural environment in border regions already provides significant defensive advantages. Marshlands and wetlands hinder offensive operations for both infantry and vehicles. Soft, waterlogged ground limits mobility for much of the year, while flat terrain offers little natural cover. Under fire, digging defensive positions in such terrain is rarely feasible. Throughout history, the natural environment has been used to reinforce defensive positions, and in some contexts this approach appears to have regained relevance.

Non-persistent anti-personnel mines

Some states and defence analysts have argued that non-persistent or “smart” anti-personnel mines could reduce humanitarian harm compared with traditional types. Available evidence does not support this claim.

These mines are designed to self-destruct or self-deactivate after a set period, yet their mechanisms are unreliable. From a humanitarian perspective, so-called non-persistent mines are neither “safe” nor “smart”: when they fail, the mines remain active and cannot distinguish between civilians and combatants; their effects are therefore indiscriminate.

The PFM-1S is one of the most documented examples of a self-destructing mine. Technical studies show that its self-destruct mechanisms are not reliable and may leave mines in a sensitive condition.[5] In general, failure rates in battle are likely to exceed those observed in testing, as confirmed by past official reviews,[6] and reliability can decline further with age, battery degradation or environmental exposure.

The ADAM (Area Denial Artillery Munition) anti-personnel mine, a 155mm artillery-delivered scatterable system developed in the 1980s, uses a battery-powered fuze to trigger self-destruction after a set period.[7] While there is limited open-source data on its reliability, even a small proportion of failures can result in long-term contamination. For clearance purposes, all anti-personnel mines, regardless of their intended lifespan, must be treated as hazardous and removed.

From an operational perspective, this unreliability creates uncertainty for commanders. If they cannot determine which mines have self-destructed or self-neutralized, they cannot predict where danger remains. Such unpredictability complicates command and control, slows post-operation clearance, and exposes both military personnel and civilians to increased risk.

Non-persistent mines are not new. They were debated extensively during the 1997 negotiations of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention and were deliberately encompassed in its comprehensive prohibition on all “victim-activated” anti-personnel mines.

Cost implications

The notion that anti-personnel mines remain an economical means of achieving military objectives is equally misplaced.

Anti-personnel mines were once regarded as low-cost defensive tools. That assumption no longer holds. Few production lines remain, and procurement, transport, and storage are subject to strict regulation. When full life-cycle costs, including post-conflict clearance, are taken into account, the overall costs far exceed initial production expenses.

Though not directly comparable, the perception of anti-personnel mines as inexpensive contrasts with the cost of other widely available systems. A US government report[8] from 1985 shows that the 155 mm artillery delivered ADAM M69 and M72, which each contain anti-personnel mines, at the time was priced to USD 4,490 each. Corrected for inflation and updated to 2025 values gives a cost of USD 13,500 per unit. The same report from the 1980s also mentions problems related to “dud” and stockpile reliability. By comparison, commercial surveillance systems are available for around USD 2,000. In weighing effectiveness, adaptability and cost, potential users are unlikely to regard anti-personnel mines as economical.

Claims that mines provide a cost-effective means of securing territory ignore the wider costs and the limited tactical value of static weapons in modern operations. The perception of low cost also breaks down when so-called “smart” mines are considered. Incorporating self-destruct or self-deactivation mechanisms substantially increases production and maintenance expenses, yet available evidence provides little indication that these features improve reliability or reduce humanitarian risk.

Why anti-personnel mines have no place on the battlefield

Warfare has changed dramatically since anti-personnel mines first appeared. Today’s battlespace depends on precision, mobility and domain integration – qualities fundamentally at odds with static, inflexible devices that contaminate terrain long after military advantage has passed. Even when assessed solely on operational or economic grounds, anti-personnel mines have been overtaken by technologies that deliver greater effect with fewer long-term costs. Their continued use is increasingly difficult to justify.

Future battlefields are likely to be even more complex, interconnected and automated, shaped by advanced sensors, robotic systems and precision guided weapons operating across land, sea and air. In such an environment, the few scenarios in which some states still claim anti-personnel mines retain tactical utility are rapidly disappearing. Research and development are accelerating in areas such as sensing, precision strike and networked surveillance, while almost no innovation is directed toward anti-personnel mines – a reflection of their diminishing military value compared with systems that are more flexible, scalable and responsive. Modern Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities – ranging from extended-range, precision-guided artillery to drone-enabled ISTAR surveillance – offer more adaptable and effective alternatives to static, victim-activated devices.

Against this technological shift stands the enduring humanitarian legacy of anti-personnel mines. Contamination from mines and explosive remnants of war continues to obstruct safe return, recovery and development decades after conflicts end; nearly thirty years after the war in Bosnia, significant areas remain affected. Reintroducing these weapons would mark a troubling step backward. Their indiscriminate effects are well documented, and many legal experts consider them inherently incapable of distinction – a cornerstone requirement of IHL upon which the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention rests. As the ICRC President has noted, international humanitarian law is made for war’s darkest moments, when people are most at risk; preserving the norm against anti-personnel mines is essential to that purpose.

At a time when some states are questioning their commitments under the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, it is vital to reaffirm the norms that protect civilians and guide responsible military decision-making. Evidence-based analysis – grounded in operational reality, technological progress and humanitarian law – must replace assumptions about the continued utility of these outdated systems.

The ICRC encourages states to draw on their own defence research and development expertise to conduct rigorous, transparent assessments of whether anti-personnel mines hold any remaining military relevance when weighed against their humanitarian impact and legal obligations. Such analysis will help ensure that decisions taken in the name of national security remain anchored in evidence, uphold the spirit and purpose of the Convention and reject the false promise of security through exceptionalism in war.

[1] Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor 2024, casualty data (2022–2023).

[2] The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction (commonly known as the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention or Ottawa Treaty) was adopted on 18 September 1997 and opened for signature in Ottawa on 3–4 December 1997. It entered into force on 1 March 1999.

[3] Foreign Affairs reports that drones account for up to 90% of armour destroyed in modern conflict is the result of attacks by drones and 80% of troop casualties. Schmidt, E and Grant, G, The Dawn of Automated Warfare, Foreign Affairs, 12 Aug 2025. The Dawn of Automated Warfare: Artificial Intelligence Will Be the Key to Victory in Ukraine—and Elsewhere

[4] See “Remote Warfare with Intimate Consequences: Psychological Stress in Service Member and Veteran Remotely-Piloted Aircraft (RPA) Personnel,” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 31, no. 2 (2025), https://www.mentalhealthjournal.org/articles/remote-warfare-with-intimate-consequences-psychological-stress-in-service-member-and-veteran-remotely-piloted-aircraft-rpa-personnel.html ; and Human Rights Watch, Hunted From Above: Russia’s Use of Drones to Attack Civilians in Kherson, Ukraine (3 June 2025), https://www.hrw.org/report/2025/06/03/hunted-from-above/russias-use-of-drones-to-attack-civilians-in-kherson-ukraine

[5] GICHD, Explosive Ordnance Guide for Ukraine (3rd edition, 2025).

[6] U.S. Government Accountability Office, Military Operations: information on U.S. Use of Land Mines in the Persian Gulf War (2002), noting that field failure rates for self-destructing mines were significantly higher than anticipated in testing. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-02-1003

[7] GICHD, Explosive Ordnance Guide for Ukraine (3rd edition, 2025).

[8] NSIAD-85-12 Results of GAO’s Review of DOD’s Fiscal Year 1985 Ammunition Procurement and Production Base Programs (page 14)

See also

- Cordula Droege & Maya Brehm, Anti-personnel mines: the false promise of security through exceptionalism in war, March 13, 2025

- Josephine Dresner, From the Middle East to West Africa: responding to the humanitarian impacts of improvised anti-personnel mines, February 8, 2024

- Ambassador Hans Brattskar, 50 steps to a mine-free world by 2025, December 19, 2019