Men and war

Militaristic attire and toys for boys are so ubiquitous they are difficult to perceive. We hardly question the messages we send to our children when we praise boys for overt exhibitions of toughness and readiness for violence. This blindness is on grotesque display in the popularity of Halloween costumes for boys that pad their little bodies to give the appearance of bulging, highly sexualized, musculature.

While it may be invisible to most, scholars in gender and masculinities studies such as Jean Bethke Elshtain, Joshua Goldstein, and Tom Digby and have shown that this merely illustrates a central way gender operates across cultures. Manhood and war are intimately connected. To be specific, self-sacrificial violence for the protection of one’s community and family is a direct way to affirm manhood and render one deserving of the entitlements afforded to men in patriarchal societies. Failure to perform this activity or to exhibit the character traits associated with it is one of the worst things a man can do. He will be subject to severe homophobic and misogynistic abuse. He will be treated as a failure as a man.

It is a myth that this warrior role and character is natural to the male sex. The fact is that men are not naturally prone to violence, toughness, or domination. They are not naturally war fighters. They must be conditioned to such things and our cultures spend enormous energy doing so. Encouraging boys to wear the costumes of warriors is a small part of this process.

The direct effects of this construction of masculinity are wide ranging. For instance, it cuts everyone other than cisgender men out of the distribution of many goods in patriarchal societies and makes everyone, including men, vulnerable to domination and violence by men. It also causes men unique harms. First and foremost, it is a source of psychological oppression for men and boys. Men learn from an early age to be ashamed of and to dissociate from important aspects of their psyches. The demand to be tough causes men enormous damage.

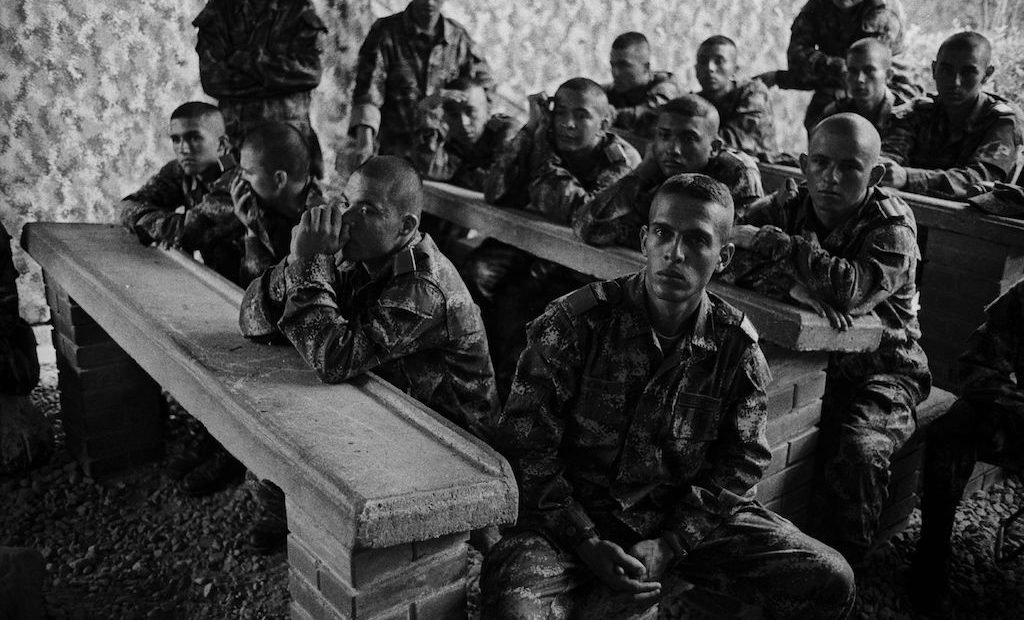

Expendable soldiers

In addition to all this, my research has found that the practice of war has been profoundly shaped by this warrior masculinity. The law and ethics of war have important features that presuppose warrior masculinity. In multiple respects soldiers are treated as expendable instruments of their communities and this is based on the assumption of the masculine nature of soldiers.

Consider how permissively the law of armed conflict regards attacks on combatants in war. While there are severe constraints on the treatment of wounded or captured combatants and some limits on the sorts of weapons than can be used against them, combatants are otherwise treated as fair game. It is legally permissible to attack combatants without regard to the justifiability of their cause or the conduciveness of the attacks to peace. The requirements of proportionality and necessity are also less stringent with respect to attacks on combatants compared to noncombatants. As Gabriella Blum concludes, ‘the striking feature of the mainstream literature is its general acceptance … of the near-absolute license to kill all combatants’ (for similar readings of the law see Larry May and Adil Haque).

Moreover, this treatment of combatants begins at home. We not only treat our opponent’s combatants as if they are expendable; we treat our soldiers as expendable as well. This is evident in the radical legal distinction between the civilian and the military realms. While civilians enjoy equal protection of their basic civil liberties, military service members are rendered instruments of the State. Service members are not protected from violations of their civil rights. For instance, a service member is legally obligated to engage in life-threatening activity when ordered to.

What justifies this treatment of soldiers and combatants?

Philosophers have struggled with this question. Foundational figures in just war theory have appealed to a presumed set of virtues that soldiers are thought to have by nature. Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf, and Emer de Vattel appeal to bravery, courage, and fortitude to justify the subordination of soldiers. These are the basic virtues of warrior masculinity. Indeed, these thinkers sometimes appeal directly to masculinity. Grotius, for instance, quotes approvingly from the poet Tyrtaeus: ‘It is a glorious and manly thing,/To risk one’s life in battle with the foe,/Protecting loved ones, wife, and native land’. And when you consider what these thinkers have to say about women—how they leave women out of civil society to labor under the control of their husbands and fathers in the household and how they claim women lack the character traits necessary for combat—it is clearer still that the natural virtues these theorists attribute to soldiers are the supposedly natural virtues of men.

This should be troubling to us all. If true, it would mean war has been theorized and practiced as a kind of gender-based violence. We have used our militaries as instruments of national security and killed our enemies with little restraint because they are presumed to be men who ought to be willing instruments of war.

Facing up to this opens new space for rethinking our attitudes toward war and the military. Once we consciously purge the presumption of gender from our theories and laws we will likely conclude that there ought to be far more constraints on violence in war and that service members are worthy of greater civil protections as home.

Men and atrocities

While legitimate legal institutions and the conventions of war rely on the presumption of gender, warrior masculinity also drives illegitimate forms of violence as well. Masculinity is an important factor explaining why noncombatants killed or detained in war are mostly men. It also explains why most mass shootings and terrorist atrocities are committed by men, especially young men.

Women are often targeted in war as women. War rape, for instance, can be understood as a gender-based atrocity. But men too are often killed, tortured, or detained simply because they are men. To name a recent example, under the Obama administration the standards for drone strikes, at least for a time, explicitly treated congregations of men as legitimate targets. It seems the association of men and war often leads participants in war to think they are engaged in a conflict with the male members of their opponent’s communities.

In addition to explaining who they target, gender also explains who groups that advocate atrocities recruit. For his new book, Healing from Hate, Michael Kimmel interviewed dozens of former members of groups that advocate extreme violence including neo-nazis and jihadists. He concludes that a central factor driving these men into (and out of) these groups is masculinity, or perhaps more accurately, threatened masculinity.

When men feel their entitlements as men are not being recognized they experience the need to have their masculinity affirmed. This can make male-dominated groups that preach violence toward loathed out-groups and treat their members as foot soldiers in an epochal conflict quite attractive. The men Kimmel talked to consistently explain that these groups filled a void in their lives: they made them feel like real men. Prior to joining these men felt vulnerable and powerless. Afterward, they felt powerful and manly.

Perhaps we should think of what movements that advocate extreme violence offer their members as manhood-on-the-cheap. The groups preaching ethnic, racial, or religious war offer the role of self-sacrificial protector of their community through violence. The content of the group’s ideology is largely irrelevant to the members. It is the masculine role that is appealing, not the ideology. Most young men that join these movements do not do so based on a rational embrace of the group’s doctrines. Rather, they join merely to be manly warriors. This frees violent movements from the expectation that their agenda be driven by reasonable evidence or accurate historical understanding or sensible moral values. As long as they provide manhood to their members, they can largely stand for whatever they want.

What this means is that combating the appeal of extreme violence will require confronting the nature of masculinity. We need to collectively reassess how we raise boys. We need to provide more space for boys to find their identities affirmed in ways other than through self-sacrificial military labor. And for those men already enculturated into warrior masculinity, we need to find opportunities for them to have their masculinity affirmed in constructive ways.

For these reasons, a humanitarian agenda must include a program to address the meaning of manhood. Doing so will contribute to greater restraints on war and more effective ways of reducing atrocities.

Graham Parsons is Associate Professor in the Department of English and Philosophy at the United States Military Academy and a Fellow of the Individualisation of War Project at the European University Institute.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not reflect the views of the United States Military Academy, the United States Army, or the Department of Defense.

See also

- Masculinity and war–let’s talk about it, Hugo Slim,

- Continuing the conversation: Which masculinities, which wars? David Duriesmith,

- The masculine condition in contemporary warfare, Gilbert Holleufer,

DISCLAIMER: Posts and discussion on the Humanitarian Law & Policy blog may not be interpreted as positioning the ICRC in any way, nor does the blog’s content amount to formal policy or doctrine, unless specifically indicated.

Comments