I came to the area of international humanitarian law (IHL) as a professional committed to seeking clarity around issues of sexual violence as a war crime. This search may at first glance appear superfluous when one knows that the prohibition of rape is one of the oldest and most basic rules of war. It was indeed explicitly prohibited (and punished by death) in the first modern code of war, the Lieber Code of 1863. The 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols of 1977 also prohibit rape and other forms of sexual violence. They do so both explicitly as well as implicitly through prohibitions of cruel treatment and torture, outrages upon personal dignity, indecent assault and enforced prostitution.

Accountability for sexual violence in war: Achievements at the International Tribunals

This law was not, however, matched with accountability until much more recently. Trials that took place in the aftermath of the Second World War, such as such as those held in Nuremburg and Tokyo, developed very little international case law on the prosecution of rape as a war crime. Decades followed, new wars began and ended, and sexual violence too often remained a hidden violation. But in the early 1990s, the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda changed this. These conflicts brought to the courtroom the suffering experienced by women, men, boys and girls, as well as their families and communities, as a result of sexual violence. The international community reckoned with the need to counter impunity and raised pointed questions as to how these breaches of law could be heard in court—under what charges, with what evidence and against whom.

The historic creation of the two ad hoc International Criminal Tribunals for the Former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda (ICTY and ICTR) saw the international community insist that crimes of sexual violence be punished and demand that individuals—including at command—level bear criminal responsibility for their commission. Successful prosecutions ensued. At the ICTY, the Furundzija case represented a landmark case concentrating entirely on charges of sexual violence.[1]

Today, there is no question that rape is a war crime in both international and non-international armed conflicts. In the Kunarac case, the ICTY also found that rape can constitute a crime against humanity in certain circumstances.[2] In the Akayesu case, the ICTR found that rape and other forms of sexual violence can ‘constitute genocide in the same way as any other act as long as they are committed with the specific intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a particular group, targeted as such’.[3] And, in cases such as Celebici and Kunarac the ICTY ruled that rape constitutes torture.[4]

Building on this jurisprudence, the development of the Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) was seen by many as a long-awaited opportunity for clarity. Delivering this, Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the ICC includes ‘rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy … enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence’ as war crimes in both international and non-international armed conflicts. And more recently, in a 2017 ruling in Ntaganda, the ICC Appeals Chamber affirmed the Court’s jurisdiction over the war crimes of rape and sexual slavery when committed against members of the perpetrator’s own armed forces,[5] reflecting the interpretation of the ICRC’s Commentary on Common Article 3.

The importance of domestic systems in prosecuting and punishing sexual violence

Through this series of cases, the ICC and ad hoc Tribunals have documented grave episodes of human suffering and successfully held individuals responsible. Yet despite this progress, sexual violence continues to mar conflicts today. It remains uniquely concealed and distinctively difficult to prosecute. Stigma, fear of retribution and misconceptions are pervasive and too often prevent victims and witnesses from coming forward or from receiving the care they need.

So whilst the impact of the jurisprudence of international courts and tribunals on this issue has been significant, domestic systems are critical to any discussion of accountability, and States must ensure that it is possible to investigate, prosecute and punish wartime sexual violence under their domestic law.[6] In some cases, better domestic implementation of existing international legal obligations is needed. Often, more measures should be taken to ease (to the extent possible) the burden of judicial procedures for victims. Appropriate sensitization and training of legal personnel, specific technical arrangements regarding time, place and mode of hearings, as well as adequate legal assistance, can help.

Responding to sexual violence: Elements of the ICRC’s approach

With this in mind, the ICRC remains committed to preventing and responding to sexual violence committed during armed conflict. We stand ready to assist States with the national implementation of these international standards.[7] In our own operations, the ICRC’s Sexual Violence Strategy 2018-2022 articulates key principles guiding our approach. It includes the principle of ‘do no harm’, a reversed burden of proof whereby we presume the occurrence of sexual violence in contexts of armed conflict unless proven otherwise, a commitment to providing a multidisciplinary and holistic response and an intersectional approach to sexual violence. In particular, such an intersectional approach seeks to take account of the complex ways in which different factors—including gender, race, class, ethnicity, disability, nationality, religion, migrant status, sexual orientation and others—can intersect and combine to shape vulnerabilities, needs, capacities and experience of sexual violence. Such an assessment is necessary to ensure that services for victims of sexual violence—as well as activities to mitigate risks—are designed and implemented in a way that makes them accessible to all victims.

***

I will never forget my experience, during a field mission with the ICRC, of explaining some of the above legal developments to women who had been survivors of sexual violence. Their sense of relief (‘what happened to me is unacceptable and a court has spoken on this!!’) and their dignity in hope that this will make a difference to other women, was immensely moving.

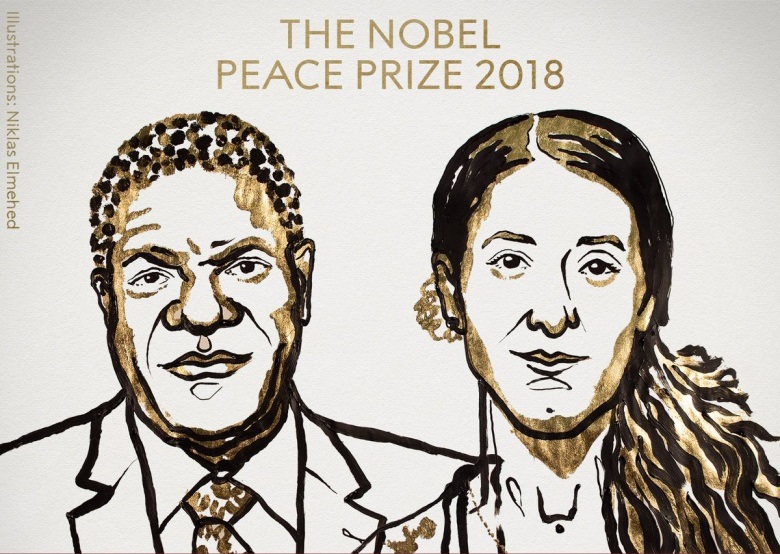

We have come a long way. And while much remains to be done, the bravery and commitment of Mukwege and Murad remind us just how much can be overcome. Their efforts, and those of many others across the world working to prevent sexual violence are as urgently needed as ever. We must continue to demonstrate our dedication to humanity in war.

***

Helen Durham has been Director of International Law and Policy at the ICRC since 2014. She has over 20 years experience in the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Helen has been a Legal Adviser to the ICRC Delegation of the Pacific; Head of Office for ICRC Australia and in various roles with Australian Red Cross including Director of International Law and Strategy and National Manager of IHL.

Helen has a PhD in IHL and international criminal law, is a Senior Fellow at Melbourne Law School and worked as the Director of Research at the Asia Pacific Centre for Military Law. She has done missions in the field with ICRC including Myanmar, Aceh, the Philippines and has been involved in international legal negotiations in New York, Rome and Geneva.

***

Footnotes

[1] ICTY, Furundzija (Trial Chamber), Case no. IT-95-17/1, Judgment, 10 December 1998.

[2] ICTY, Kunarac (Trial Chamber), Case no. IT-96-23 & 23/1, Judgment, 22 February 2001, para. 782.

[3] ICTR, Akayesu (Trial Chamber) Case no. ICTR-94-4-T, Judgment, 2 September 1998, para. 731.

[4] ICTY, Kunarac (Appeals Chamber), Case no. IT-96-23 & 23/1, Judgment, 12 June 2002, para.150; ICTY,Delalić (Trial Chamber) (Celebici Case), Case No. IT-96-21, Judgment, 16 November 1998, para. 495.

[5] ICC, Ntaganda (Appeal Chamber), Case no. ICC-01/04-02/06, Decision on the Jurisdiction of the Court in Respect of Counts 6 and 9, 15 June 2017.

[6] Rule 158 of CIHL: ‘States must investigate war crimes allegedly committed by their nationals or armed forces, or on their territory, and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects. They must also investigate other war crimes over which they have jurisdiction and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects.’

[7] The ICRC’s Advisory Service provides technical advice to States on national implementation measures.

Magnificent achievements on behalf of all women by the IRC (International Red Cross).

It is clear this knowledge must be implemented internationally in order for continued success for all women effected by these hedious acts by many in trusted for their safety.

Regards/James

Domestic systems are not only critical, they are also fundamental to ensuring lasting accountability. In this regard, Doctor Mukwege recently praised the strides made by the domestic Congolese military justice system. See, “Lutte contre les violences sexuelles: Dr Mukwege félicite la justice militaire”, Radio Okapi, 5 September 2018 (https://www.radiookapi.net/2018/09/05/actualite/justice/lutte-contre-les-violences-sexuelles-dr-mukwege-felicite-la-justice?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+radiookapi%2Factu+%28Radiookapi.net+-+Actualit%C3%A9%29).

Only in February 2016, nearly 14 years after its ratification by the DR Congo in April 2002, was the Rome Statute domesticated by amendments to the Congolese Penal Code. However, domestic prosecution of these most grievous of crimes was not delayed, thanks to the bold initiative of Congolese military magistrates to apply the Rome Statute directly in courts-martial via the DR Congo constitution’s supremacy clause. By prosecuting and obtaining convictions in Congolese courts on charges brought directly under the Rome Statute’s substantive provisions, Congolese military magistrates actuated the principle of ICC complementarity to domestic systems, and have spawned a body of domestic Congolese jurisprudence.

The development of this law is thematically chronicled by Professor Jacques B. Mbokani, of the University of Goma, in his study “Congolese Jurisprudence under International Criminal Law: An Analysis of Congolese Military Court Decisions Applying the Rome Statute” (Johannesburg: Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, and African Minds, 2016 (French original) and 2017 (English translation)), and his recent follow-on “La Jurisprudence congolaise relative aux Crimes de Droit international 2016-2018” (Kinshasa: Club des amis du droit du Congo, 2018, discussing cases brought since domestication of the Rome Statute).

A testament to Congolese military justice’s international leadership in domestically implementing International Criminal Law, including the repression of sexual violence in armed conflict, is the fact that one of its senior magistrates was selected as the inaugural Chief Prosecutor for the Special Criminal Court for the Central African Republic.

In the mixed post- and on-going conflict environment of the DRC, military justice remains critical to the overall Congolese justice sector. Only since 2013 has legislation been adopted to begin shifting jurisdiction over Rome Statute-defined crimes from military to civilian courts, and the civilian criminal justice sector looks to the military for guidance, training and precedent in exercising its newly acquired concurrent jurisdiction. However, though the gains realized by Congolese military justice these past 10+ years have been great, continued support from the international community remains critical as the Congolese continue to build a foundation for their criminal justice system throughout the vast territory of the DRC, in order to ensure enduring accountability for the most grievous of crimes, including wartime sexual violence.

David A. Buzard, Esq.

Kinshasa DR Congo | Norfolk Virginia

http://www.linkedin.com/in/davidbuzard