In your work, you have highlighted how public attitudes and discourses about violence have shifted since 9/11, with violence being increasingly accepted as a legitimate means to pursue national security goals. The ICRC has also recently highlighted people’s general increased acceptance of torture. How, in your view, should humanitarian organizations respond to this?

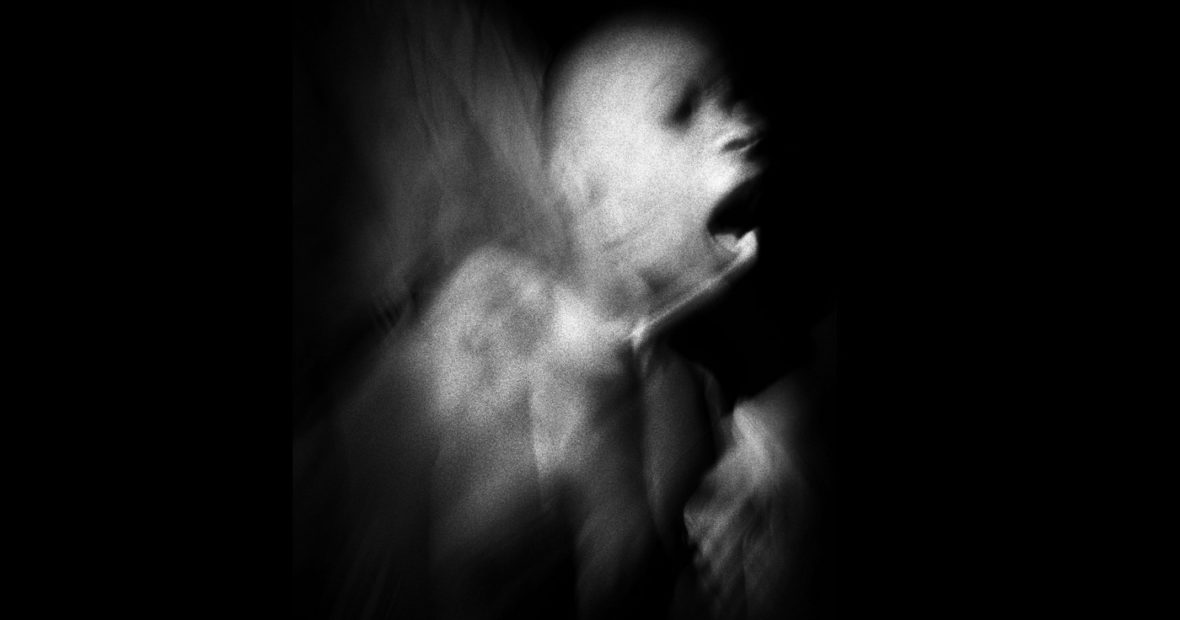

Violence is not some abstract concept. It is an attack upon a person’s dignity, their sense of selfhood, and their future. Violence is both a crime, as it seeks to destroy the image we give to ourselves as valued individuals, and a form of political destruction, which stabs at the heart of human togetherness.

What defines the human condition is not simply that we live with this capacity to be wounded. We also have the capacity to think and imagine better worlds. So this is what is really at stake here. To accept violence is to normalize the wounds that tear apart the bodies of the living. That is why violence and especially torture is so pernicious, particularly as it becomes justified and more socially accepted.

Not only does violence generate violence, continuously, endlessly. The memory of violence can also have such a hold over us that the ways we come to read the past are filtered through the most brutal lens.

The concept “Humanity” is subject to this historical analysis. Whilst the term has a complex history, it really became significant after the horrors of World War II. Especially when confronting the reality of the Holocaust. Humanity in this regard emerges as an ethical and juridical problem out of the realization of the very worst that humans were capable of doing to one another. Organizations such as ICRC thus respond to this reality – by being confronted with violations of human dignity and the horrors of war.

You also stress that in contemporary society many phenomena – from popular culture to the representation of terrorist groups and the ongoing terror wars in mass media – can desensitize people to violence. The spectacle of violence and torture has become banal. Are people becoming immune to the horrors of this world?

Some forms of violence or what we prefer to call force or collateral damages can be fully reasoned, whilst other clearly go beyond the tolerance threshold. Let’s connect this directly to the problem of torture.

What we have witnessed since 9/11 has been a notable public shift in the modalities of violence, from spectacular attacks towards violence that is more intimate and individualizing. Such violence seems to actually be more intolerable for us. There is something about the raw realities of intimate suffering which affects us all on a human level.

Such intimacy has also fed into and been driven by the pornographic violence of popular culture. Movies and video games in particular excel in showing the intimate realities of violence for entertainment value alone. Our societies are so overwhelmed by images of suffering that it is as if we are continuously walking through an interactive version of what the author J.G. Ballard called the Atrocity Exhibition.

And yet I think it would be far too reductive to say that people are simply immune to such violence. The fact that people may turn away from the violence is arguably an all too natural reaction to its forced witnessing.

What I think is more a problem is how to find meaningful solutions to the raw realities of violence that don’t end up creating more anger, hatred and division. People are certainly frustrated that the daily exposure to violence doesn’t become a catalyst to steer history in a more peaceful direction.

Conflicts around the world are changing and evolving. There is an undeniable global component, which we can see clearly in recent attacks claimed by ISIS. Conflict is no longer contained in the war zones where the ICRC is working but spilling over in cities. What does this mean for the laws of war and how can the ICRC respond to this spilling over of violence?

You’re correct to point out that everywhere has now become a battlefield. We can no longer distinguish between friends and enemies. The inside as a safe haven and the outside as a place of lawlessness. We can no longer identify times of war from times of peace. It seems that we are engaged in a global civil war, which has become so normalized that the term “war” is no longer declared.

Are we still actually in a war on terror, for example? Politicians no longer feel the need to say it, yet nobody has actually declared it to be over. This situation demands new global ethical thinking of which organizations such as the ICRC must have a considered voice, beyond the juridical scope.

“People are frustrated that the daily exposure to violence doesn’t become a catalyst to steer history in a more peaceful direction.”

What are the new trends in violence today? How can an international humanitarian organization like the ICRC respond to this in your view?

What is troubling is the notable liberation of prejudice on all sides. I have already spoken of the advent of the catastrophic individual, who is now capable of being the author of widespread devastation and slaughter. We cannot simply deal with this violence by responding to its consequences.

What is required, and where the ICRC might make a truly positive intervention, concerns the yet to be answered question about how we begin to educate about violence today with proper ethical care and political consideration for the subject. This requires a sustained global conversation between many actors who know first-hand the realities of violence and the way it truly destroys any humanitarian claims.

Given the new trends in violence, do you think that humanitarian organizations still have a role to play? What should that be in your opinion?

Education. I am not denying the need for on the ground responses to deal with the legacies of war and the individual and social traumas they produce. This requires sustained engagement by multiple organizations. But unless we start to develop the necessary educational tools, which bring together international organizations, advocates, community leaders, academics, artists and cultural producers, and everyday citizens, then we will continue to see violence justified for the furtherance of political goals.

A recorded version of the panel discussion will be made available.

***

Dr. Brad Evans is a political philosopher, critical theorist and writer, whose work specialises on the problem of violence. The author of some ten books and edited volumes, along with over fifty academic and media articles, he serves as a Reader in Political Violence at the School of Sociology, Politics & International Studies, the University of Bristol, UK.

Achille Després works in internal communications at the ICRC. He holds a dual Master’s degree in Management of International and Public Affairs from Sciences Po and Bocconi University (Milan).

Read more about the historical, legal, social, psychological and political questions relating to torture in this issue of the International Review of the Red Cross. The article “Humanitarian care and small things in dehumanised places” by Paul Bouvier discusses the issues of vulnerability, trauma and resilience of victims of violence.

Comments