Translated by Heather Thompson.

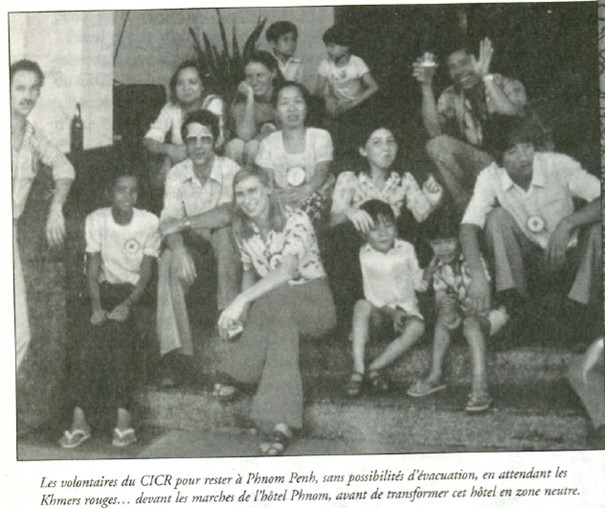

On 17 April 1975, Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, was seized by the Khmer Rouge, a self-proclaimed nationalist-communist group. The fall of Phnom Penh left a lasting mark on the history of Cambodia and that of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Cambodia had already been weakened by years of civil war and political instability, and the ICRC’s work in the country during this period was distinctive in two main respects. The first was that the ICRC was one of the few humanitarian organizations active in the country before the fall of Phnom Penh; the second was that it was the only organization of which a handful of delegates (fourteen, to be precise[1]) voluntarily stayed in the country to continue their humanitarian work. All foreigners, including ICRC staff, had been ordered to leave. But the delegates were determined to carry out their work to the very end and decided to stay. Eventually, they would be forced to take refuge in the French embassy

What is the place of humanitarianism under such circumstances? The ICRC’s presence in Phnom Penh in 1975 shows that humanitarian work is a high-wire act, especially when the authorities are distrustful and dialogue is impossible.

Numerous documents in the ICRC’s audiovisual archives speak to the difficulty of the organization’s work in Cambodia. The diversity of the organization’s humanitarian activities in the country in the early 1970s is evident in photographs of camps for displaced people, images of a neutral zone being set up in Phnom Penh and pictures of ICRC staff and Cambodian Red Cross Society volunteers working together in Cambodian hospitals. Video recordings, mostly documentary in nature, provide insight into the humanitarian situation in the country over the years, including Crisis Cambodia and The Border People: Aspects of ICRC Action on the Thai–Cambodian Border in 1984. There is also a video of André Pasquier, who was head of the ICRC delegation in Cambodia in 1975, recounting his experiences, as well as his written recollections, which set out in detail what happened in Phnom Penh in 1975.[2] Recordings of radio transmissions give insight into key moments for delegates on the ground: physician Pascal Grellety, head of delegation François Perez (André Pasquier’s predecessor) and Suzanne Jolivet, a member of the mobile medical team. Peter Kunz, who was a radio operator in Phnom Penh in 1975, also contributed his recollections to this article.

This article sets out events in chronological order, with a special emphasis on their climax in April 1975. It then focuses on the ICRC’s activities, rather than giving an exhaustive account of historical events (including the Cambodian genocide). Finally, it takes a critical look back at the ICRC’s work in Cambodia during this period, in particular how the mission and the ICRC delegates’ decision to stay in the country were received in the press. The recollections of Sylvie Léget, a photographer and press attaché for the ICRC in 1989, provide insight into the work the ICRC carried out in refugee camps once it was able to return to Cambodia.

I. The ICRC in Cambodia during the civil war (1967–1975)

Historical context

The eruption of violence in 1967 began with an uprising in the Cambodian countryside, the result of years of political tension in the country. The revolt transformed the country’s political landscape, fuelled by a deteriorating economy and the rise of the communist Khmer Rouge movement. The head of state, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who was regularly criticized for his passivity, temporarily entrusted power to the openly anti-communist prime minister and general Lon Nol in 1969, who was supported by the United States.

In 1970, a coup took place, marking a new era: the monarchy was abolished and, led by General Lon Nol, the Khmer Republic was established by parliamentary vote. Norodom Sihanouk went into exile in Beijing, where he allied himself with the Khmer Rouge. From China, he formed the Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea and urged Cambodians to take up arms against Lon Nol. His low popularity meant that few listened. Further headwinds came in the form of the military aid provided by the United States to Lon Nol’s government to aid the fight against communist forces.

Meanwhile, the Khmer Rouge, bolstered by other communist factions, continued to advance. The group closed in relentlessly on Phnom Penh, ultimately seizing control of the capital in 1975.

The ICRC delegation in Cambodia

With Cambodia in the grip of political upheaval and economic uncertainty, people were desperately in need of help: huge numbers of civilians were displaced, and with that displacement came hunger, disease and the harsh living conditions of camps. Not only did the ICRC have to contend with the enormous challenge posed by those humanitarian needs, but the political transition from a monarchy to a military government necessitated a number of organizational changes. After Sihanouk was deposed, the Cambodian Red Cross Society dismissed his wife, Princess Monique, from her position as president.[3] The ICRC had been present in Cambodia since 1967 and already worked with the National Society regularly to distribute food to displaced people.

Battambang Province, Beng Khtum. Princess Monique, president of the Cambodian Red Cross Society, distributes aid to displaced people. Photographer unknown, 23 December 1968, ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-E-00066.

Despite the political instability and other changes in the country, the Cambodian Red Cross Society continued to play a central humanitarian role, and it was very active in tracing people who had lost touch with loved ones, requests for which mounted as a result of the growing number of displaced people.

Phnom Penh. Tracing service of the Cambodian Red Cross Society. M. Vaterlaus, March 1973. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00001-21.

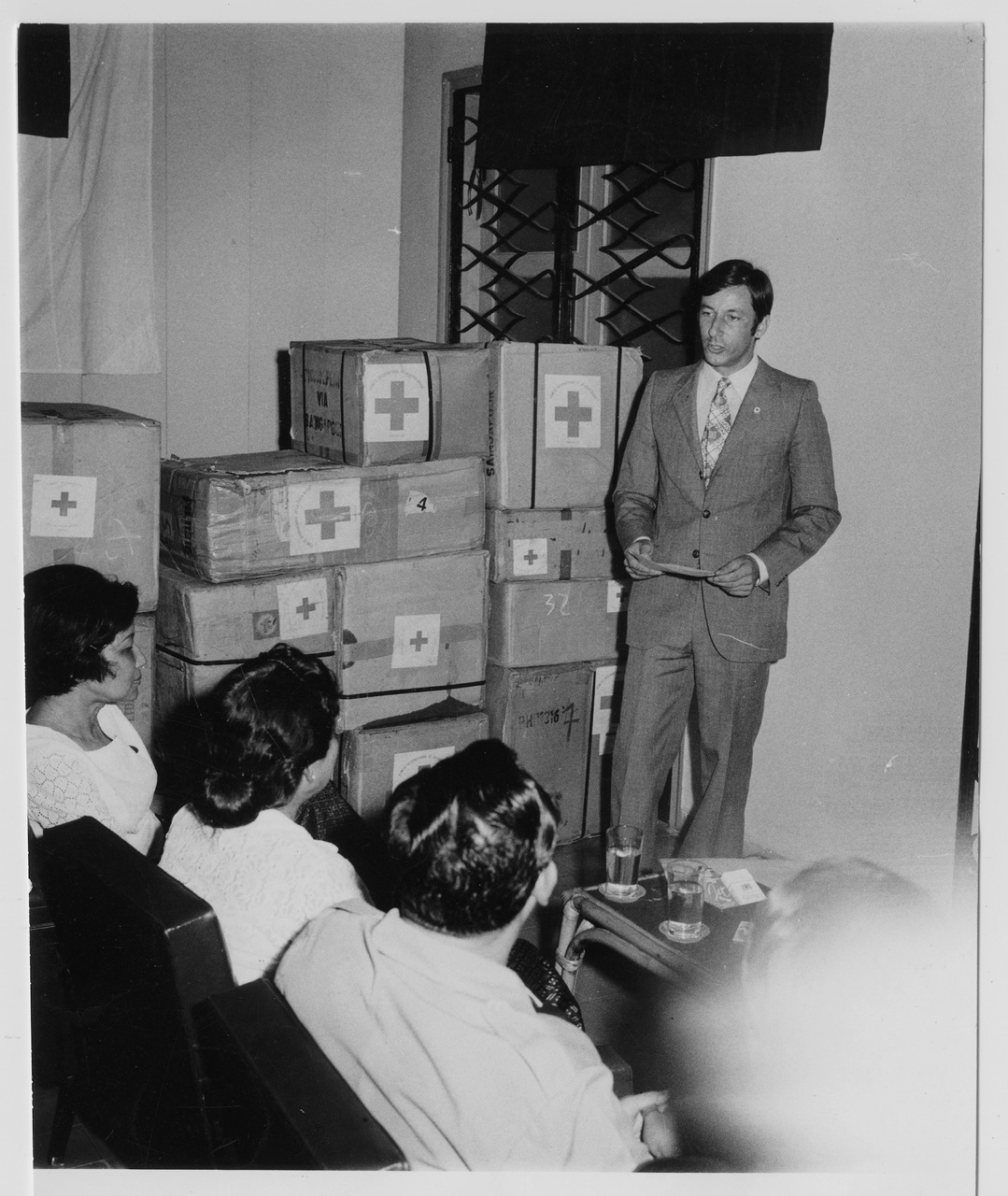

The ICRC, meanwhile, brought aid primarily to orphans and war victims in camps, distributing enriched milk to children, providing medical care and delivering medications.

Phnom Penh, headquarters of the ICRC delegation. An ICRC delegate delivers a speech as ICRC donations are handed over to the Cambodian Red Cross Society – 99 boxes of medications and 593 cartons of milk. Unknown photographer, 5 April 1973. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-E-00192.

II. The ICRC in Cambodia in 1975

Unpredictability reigns

Upon examination of the archival evidence of the ICRC’s activities in Phnom Penh, something surprising surfaces: against all odds, despite the local population’s immense needs – in particular around food shortages and raging disease such as the measles, dysentery and malaria – their morale was good. This was reported with surprise by Dr Pascal Grellety, a doctor in the field for the ICRC and the cofounder of Doctors without Borders, in an interview on 11 February 1974.[4] While the medical team had expected deserted streets, Grellety was astonished to find “full terraces,” “smiling faces” and “children at play.” It seemed that Cambodians had learned to live with war. Peter Kunz said much the same: the ICRC delegates, and Westerners more generally, were the only ones “counting the rockets” that fell at random in the streets. And on a radio transmission on the situation in Phnom Penh on 31 January 1975, François Perez says on behalf of his colleague on the medical team that the local morale was good and that provisions had been secured.[5]

In a transmission on 16 February, though, Pérez was more nuanced.[6]

He expressed concern about the rockets that continued to bombard every neighbourhood and noted the increasing isolation of the capital, which was highly dependent on agricultural provinces. The war, along with poor weather conditions, had drastically reduced the quantity of food being transported into the city, and Phnom Penh was now entirely dependent on external aid. Some NGOs were still running soup kitchens, and the ICRC continued to distribute milk and develop a medical-nutritional programme.

André Pasquier, who arrived in Phnom Penh on 29 January 1975 to relieve Pérez as head of delegation, also testified to the contradiction visible in life in Phnom Penh. He wrote:

When I arrived in Phnom Penh, I expected to see a capital bruised and battered by five years of war. To my astonishment, the city stretched out before me with its wide, shady avenues, colonial villas surrounded by flowering gardens, pagodas and palaces with roofs curved like horns and decked with glazed tiles, floating restaurants moored along the banks of the Mekong and its streets teeming with life. How could I not give in to the seduction of this deliciously provincial city, wrapped as it was in a tropical damp in which all worries vanished? Life seemed to play out happily. There was only one checkpoint between the airport and the city centre, with few soldiers visible on the streets. Yet behind this peaceful, illusionary scenery, war was lurking some 15 kilometres away, and each evening it raised its voice when the curtain of night abruptly fell and when the bustle of the streets gave way to muffled silence. In a hum of distant thunder, the artillery barrages of Phnom Penh’s defenders filled the night with the dull rolling of a bass drum, followed in bursts by the shrill whistles and clamour of the Khmer Rouge’s Chinese rockets, falling randomly on the city. [7]

In 1975, the already-acute needs of the Cambodian people were exacerbated by the continuing war, instability and political uncertainty. The Khmer Rouge’s advance on and seizure of the capital changed the playing field and opportunities for the ICRC to respond to those needs, which had reached their apex.

Increasing isolation

Far from resolving, tensions in the country mounted from all sides. On March 14, Sihanouk sent a telegram from exile in China urging the ICRC and all diplomatic representations to evacuate foreign personnel, whose security was no longer guaranteed.

From the end of March, one embassy after the next closed its doors and organized its citizens’ departure. Some National Societies’ medical personnel abruptly ended their assignment.

4 April

The Swiss Red Cross team of Dr Richner left this morning for Bangkok.

5 April

The Swedish Red Cross’s surgical team also evacuated Phnom Penh.[8]

In response to Sihanouk’s warning, Roger Gallopin, president of the ICRC’s Executive Board,[9] expressed reservations, in particular about evacuating medical personnel who could not “abandon the sick without having handed them over to competent hands”. On 8 April, Sihanouk provided an explanation: “… we want to avoid at all costs unnecessary complications with foreign countries and international organizations that have collaborated with the so-called Khmer republic. … With respect to humanitarian matters, we claim the right to handle them alone, without any foreign interference. In this regard, I would remind you that we not members of the International Red Cross, nor of the UN or UNESCO.”[10]

Rumours of escalating hostilities swirled around diplomatic circles. Only four embassies kept their doors open – those of the United States, West Germany, Czechoslovakia and France.

On 11 April, André Pasquier convened an emergency meeting with delegation staff after speaking with the American ambassador, John Gunther Dean. The Khmer Rouge would seize the capital in just a few days, and ICRC personnel had been given a final deadline to leave the country.

Pasquier had decided to stay anyway. It was a controversial choice, but he deemed it “the only decision I will never be ashamed of”.[11] He laid out his reasons for staying to his colleagues and told them to choose on their own what seemed right to them. Of the 24 present, 14 followed his lead. When asked in an interview why he stayed, Peter Kunz said, “I was still a key person because of the radio post. I couldn’t abandon my team, just as the medical teams couldn’t all leave.”[12]

The decision, which the Americans called irresponsible, did not get the green light from Geneva for two days and only after several requests. Once it did, the ICRC truly became the only humanitarian organization active in Cambodia.

A ceasefire proposal with consequences

In April 1975, there came another disruption to the ICRC’s work. Amid the political upheaval, the ICRC received a request to send a message to the opposing party with a ceasefire proposal. Pasquier reported: “During the day of 16 April, I met with Prime Minister of the Republic Long Boret, who requested that I send an appeal from his government to the other party.”[13] Owing to its intrinsically neutral and non-partisan nature, the ICRC became a preferred intermediary between Sihanouk’s government in exile in Beijing, which was allied with the approaching Khmer Rouge, and the military government, which was still in power but weakened and headed toward an imminent fall.

Unfortunately, the initiative was not well received. The response from Beijing, after some delay, was virulent. Not only was the ICRC not recognized as neutral, but it was accused of sympathy with Lon Nol for not having officially recognized the Khmer Rouge. The Guardian would later state the ICRC believed that the reaction to the ceasefire offer had been deliberate, part of a wider plan to expel all foreigners, regardless of their role.[14]

How will the Khmer Rouge behave with us who have chosen to stay despite Sihanouk’s warnings and exacerbated our situation by establishing a neutralised zone and acting as neutral intermediaries? Have I been naïve? All of my illusions of a possible dialogue with the victors are evaporating.

– André Pasquier[15]

The neutralized zone at Le Phnom hotel

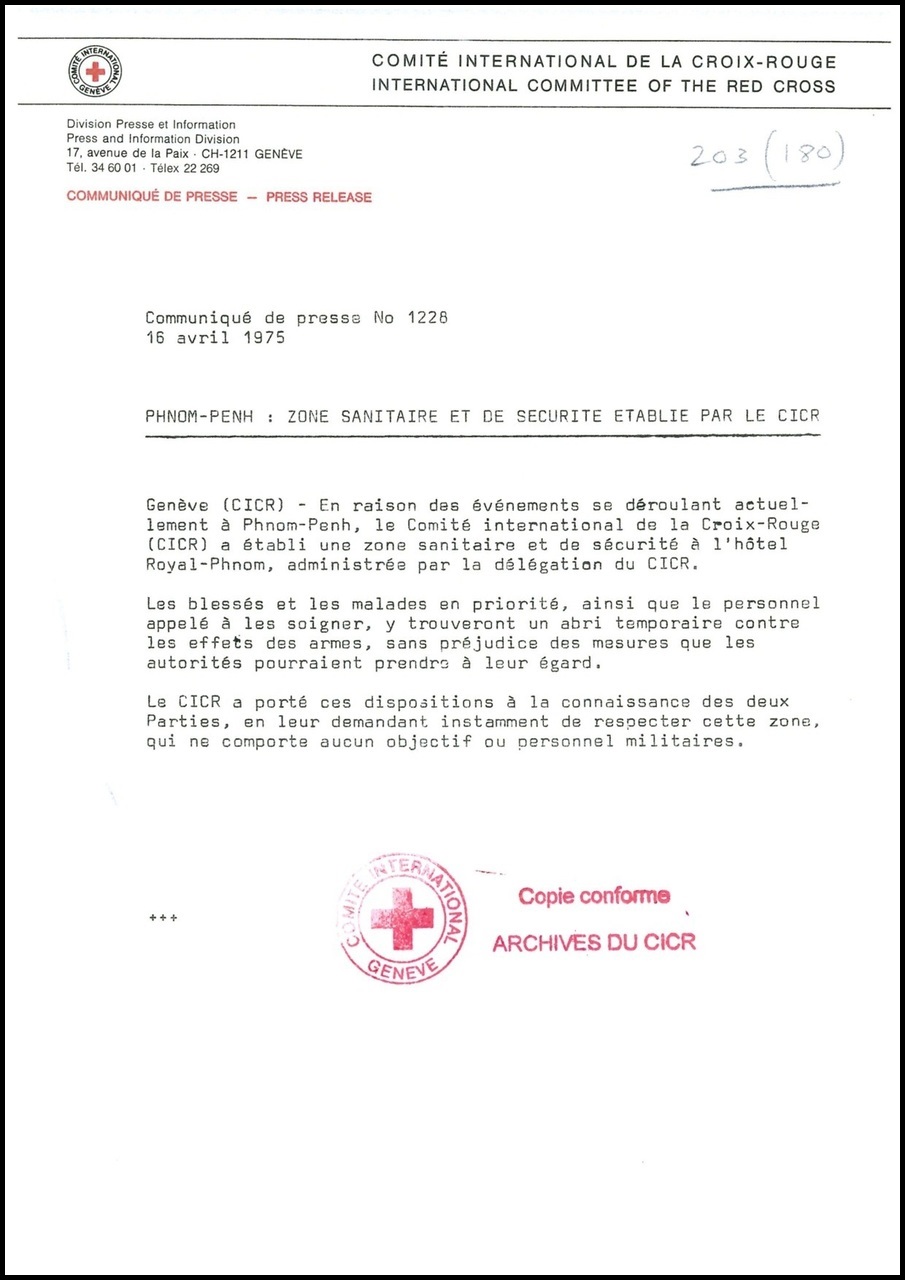

To protect civilians from bombardments and get basic aid to them, the ICRC delegation decided to turn the Le Phnom hotel, in the centre of the capital, into a neutralized zone. Temporarily creating a makeshift shelter enabled ICRC medical teams to treat the wounded in spite of limited resources and personnel. Pasquier made the request to establish the neutralized zone to Prime Minister Long Boret (of Lon Nol’s government) when he delivered the ceasefire message early in the morning on 16 April.

On 16 April at 5pm, the hotel was established as a neutralized zone, marked by large red cross flags on the building’s facades. While the move was well received by most of the foreigners present, it was controversial with some others, including Christoph Maria Fröhder, a German journalist who considered it to make no sense in a city of two million people, especially without a guarantee that the Khmer Rouge would respect it.[16] ICRC delegates were tasked with standing watch at the entrance to ensure no one entered the building with a weapon. Many locals flocked to the hotel, hoping to take refuge for a few days until peace was restored.

Phnom Penh. Street scene. M. Mercier, 1975. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00003-01.

The morning of 17 April brought a brief glimmer of hope. While the delegates who had stayed in the capital were busy bringing aid and medical attention to those who had taken refuge in the hotel, the city grew unusually quiet. The government army surrendered, and the Khmer Rouge burst into the city. Marching decisively, faces stern, the Khmer Rouge ordered the opposing soldiers to lay down their arms.[17] The crowd’s silence turned to joyful cheers at the thought of the war ending and the monarchy, headed by Norodom Sihanouk, returning.

“At that time of year, Cambodians were celebrating the Khmer New Year. Many said to themselves, ‘Sihanouk is coming back – it will be a celebration!’ But that morning, their hopes would be crushed,” recalls Peter Kunz.[18].

Indeed, the joy was short-lived. Shortly after arriving and seizing control, having just walked among the jubilant crowd a few minutes before, the Khmer Rouge ordered everyone to evacuate the city.

At the hotel, the ICRC delegates bore the brunt of the unexpected shift in circumstances. The ceasefire matter had riled the authorities and undermined the ICRC’s legitimacy. Nevertheless, they made one final attempt at negotiation. Shortly after the Khmer Rouge entered the city, one of the army’s representatives went to the hotel. Pasquier met with him and tried as best he could to explain the reasons for the neutralized zone, the ICRC’s activities and mandate, and how the organization functioned under the Fourth Geneva Convention, on the protection of civilians during wartime.[19] The meeting ended in failure. Pasquier recounts:

“I explained to the representative why the [neutralized] zone was there, what the objectives were and what we intended to do with it. I also laid out for him the personnel I had, what we were capable of and that we could bring them aid to the extent they wanted it. He took note and told me that the Red Cross should not be involved in politics. It was perhaps a somewhat surprising response, but an understandable one given that we had transmitted the last surrender offer from the government, which had been very poorly received and had provoked a rather sharp response from the government-in-exile’s representatives. Just that morning, Radio Beijing had launched into a diatribe against the people who had dared to extend a final lifeline to the Republic’s puppet government when our role, under the Geneva Conventions, was limited to that of a neutral intermediary.”[20]

On 17 April at 11:30am, the combatants evacuated the hospitals by force and, at 4pm, under the threat of arms, so was the hotel. Gradually, the capital became deserted and the delegates, like other foreigners, were forced to abandon their work and take refuge in the French embassy.

Phnom Penh. Le Phnom hotel after being turned into a neutralized zone by the ICRC. M. Mercier, February 1975. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00008-02.

Two metres away, a young Khmer Rouge soldier with a crazed look, shouting, pointed his revolver point-blank in the face of Streijfert, a Swedish delegate, who made a shield with his body and refused to let the soldier advance while screaming, “Go out! This is a Red Cross zone! You have no right to enter it.” My blood ran cold. I yelled at Streijfert to get out of the way. He yielded. The soldier lowered his weapon and entered the hotel. I realized, my face ashen, that we had just escaped what could have been the beginning of a massacre.[21]

ICRC press release announcing the establishment of a “medical and security zone” in Phnom Penh. ACICR B AG 203 042.001–02.

The International Red Cross delegation had decided to set up a refuge in Le Phnom hotel to save civilian lives. After long opposing it, the Phnom Penh government gave its consent on the afternoon of 16 April. From Beijing, Prince Sihanouk flatly rejected the proposal. In spite of this, the Red Cross had tried to do something, aware of the fragility of the shelter it was offering.

– François Ponchaud, Cambodge, Année Zéro

Phnom Penh. Crowd in front of the neutralized zone at Le Phnom hotel. M. Mercier, February 1975. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00008-03.

Phnom Penh. Crowd in front of the neutralized zone at Le Phnom hotel. M. Mercier, February 1975. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00008-03.

Phnom Penh, Le Phnom hotel. Meeting between two ICRC delegates and a member of the government-in-exile’s armed forces after the fall of Phnom Penh. F. Zen Ruffinen, 17 April 1975. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00008-04.

Upon seeing the photograph above, taken during the meeting led by Pasquier (bottom left), Peter Kunz identified the Khmer Rouge representative, with a red and white krama wrapped around his neck. “He didn’t speak a word,” said Kunz, “even though he spoke French and understood everything that was said to him.”

The French embassy and forced displacement of civilians

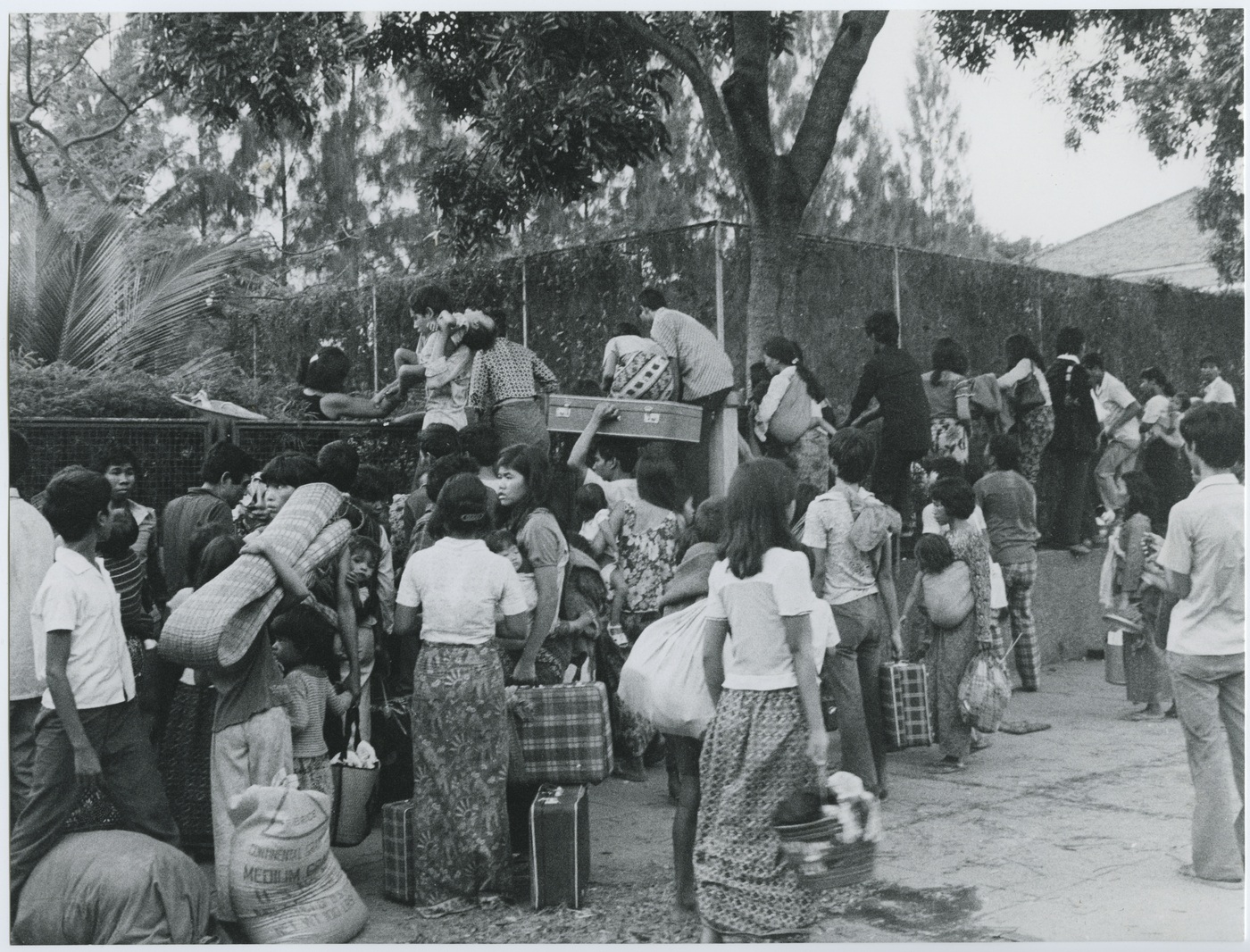

Around 4pm, a car drove down Monivong Boulevard blaring out an evacuation order. “Anyone who has taken refuge in Le Phnom hotel and all foreign personnel must leave the premises before 5pm.” For the thousand-odd refugees and Red Cross staff there, this meant panic – where could they go? The foreigners wanted to head for the French embassy, but the Cambodians begged them: “Don’t abandon us!” They left in an unimaginable chaos, abandoning equipment and medicines.

– François Ponchaud, Cambodge, Année Zéro[22]

Upon entering the French embassy, ICRC personnel were forced to give up all humanitarian activities. All of them, delegates included, were regarded as merely foreign nationals taking shelter. Red cross emblems were removed and hidden, and the organization’s vehicles were not allowed onto the premises.[23] Moving about was impossible: the journalists, diplomats, delegates and other foreigners had to stay within the shelter of the embassy walls, suffering through the uncertainties and forced idleness of each new day.

Phnom Penh. Refugees at the French embassy. Photographer unknown, April 1975. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-E-00085.

17 April 1975 – I remember it as if it were yesterday. We followed instructions and went to the French embassy. I remember this photo, the one of the suitcases everyone was throwing over the fence – I did the same. I also remember that the ambassador had told us, “You worked with the old government, but we’ve recognized the new government.” I had come in an old Peugeot 404, but we couldn’t enter with our cars. A Khmer Rouge soldier had pointed his pistol in my direction and shouted, “Get out!” before taking the car and leaving, the red cross still on it.

– Peter Kunz

Three thousand people took shelter at the embassy, including many Cambodians, who were forced out by the Khmer Rouge shortly after. Some representatives of the old government, including Lon Nol and Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak, also took refuge there briefly before being arrested by the new authorities, who had already drawn up a list of traitors condemned to death. By 22 April, Phnom Penh was emptied of its two million inhabitants. The embassy, with its impromptu residents, was the only island of human presence in the deserted capital city.

The ICRC delegation would stay in the embassy until 30 April, when an organized convoy left for Thailand. Until then, the delegates were themselves refugees of a sort within the embassy. “We didn’t know how long we were going to stay like that,” said Kunz.[24] He said that the foreigners trapped in the embassy were forced to drink the condensate water from the air conditioners. They also drank the yellowish water from the Mekong River, delivered by Khmer Rouge soldiers, which they filtered with a little chlorine and the embassy’s bedsheets. The authorities shut off the water to force out the last of the Cambodians who had taken shelter on the premises. Once they were gone, a few thousand foreigners remained.

Pasquier and his team were plunged into complete uncertainty for several days.

“[André] was constantly preoccupied,” said Kunz. “I would always see him wandering around the embassy garden, thinking. He never stopped asking himself whether he had made the right decision.”[25]

On 27 April, the Khmer Rouge confiscated all of the transistor radios they found, limiting communication with ICRC headquarters in Geneva. Only one radio, which Kunz had taken from the hotel and hidden, enabled the delegates to continue monitoring the situation discreetly. They also intercepted messages from the ICRC delegation in Bangkok and learned that it had sent a vehicle to get them in Phnom Penh, which was confirmed the next day by Jean Dyrac, the consul in charge of the embassy.

On 30 April around 5am, a convoy pulled up in front of the embassy to evacuate all of the foreigners who had been held captive in the embassy, including the entire ICRC delegation. The evacuation route was deliberately winding, passing through a deserted town, then a forest, then the border city of Poipet, which sat on a river across from Thailand, with a bridge in between. The towns and cities that the foreigners glimpsed on the way were empty. Phnom Penh itself, full of jubilant crowds on 17 April, was deserted.

The convoy arrived safe and sound in Thailand, an enormous relief for André Pasquier. He returned home to Geneva on 10 May.

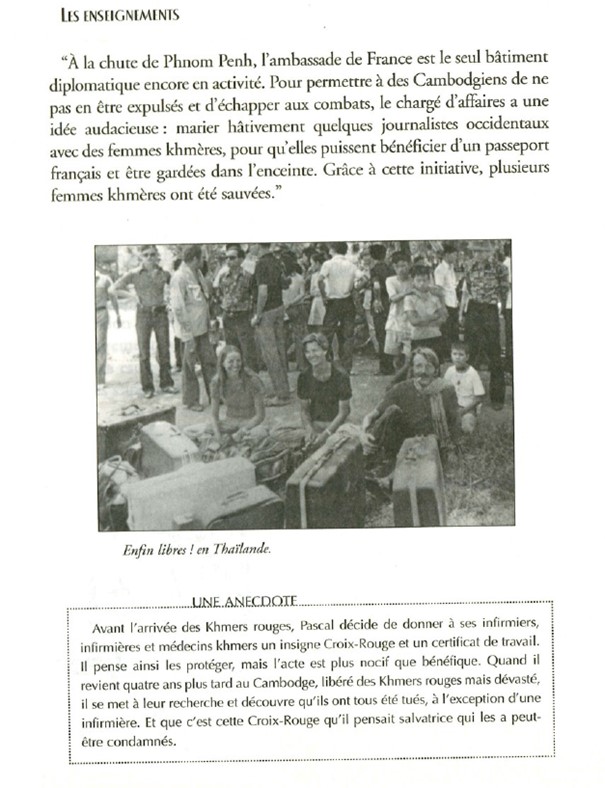

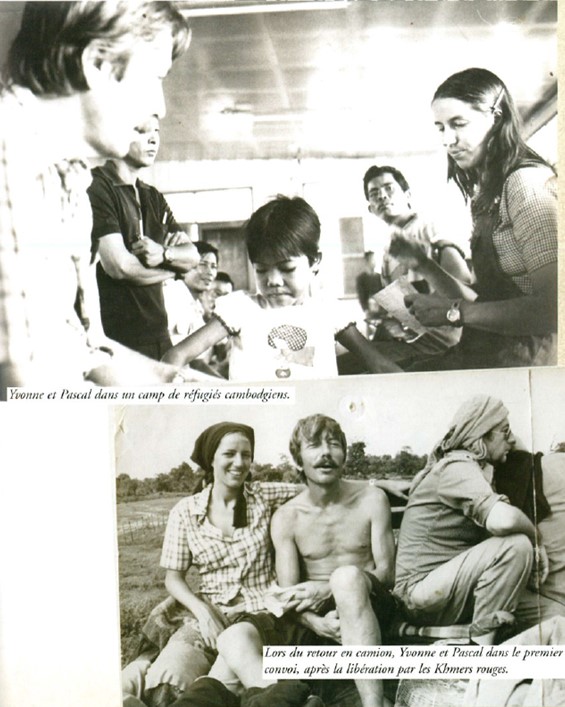

Excerpts from Toute une Vie d’Humanitaire: 50 Ans de Terrain d’un Médecin-Carnettiste, by Pascal Grellety and Sophie Bocquillon (Elytis edition).

Grellety is pictured in the first image, seated at right.

III. After-effects: media criticism and legacy

Criticism in the press

In Geneva, the end of the mission had provoked concerns. When André Pasquier returned home, he learned that the German journalist Christoph Maria Fröhder, who had been so sceptical of the establishment of the neutralized zone, had publicly attacked the delegates. He accused them, among other things, of having “fled in panic” from the neutralized zone to the French embassy, “abandoning three wounded people”, and called it an “international scandal”.[26] This blistering critique appeared before public opinion on the drama in Phnom Penh could take shape, and Pasquier and Pascal Grellety were quick to refute it. It was a delicate situation for the ICRC, but it ended shortly thereafter with an official communiqué stating that, after discussion, the two parties remained convinced of their positions and considered the matter closed, if unsatisfactory.[27]

Article in the Tribune de Genève, 14 May 1975. ACICR B AG 063-424. Of the media criticism, Peter Kunz said, “For my part, I think André kept his composure. There were some journalists who were more or less on the ICRC’s side in the controversy, but it wasn’t a sure thing.”

Fourteen years later

The ICRC was only allowed back in Cambodia in 1979, after the Vietnamese overthrew the Khmer Rouge and proclaimed the People’s Republic of Kampuchea. In 1977, internal struggles had caused a rupture in diplomatic relations between Vietnam and Cambodia. Amid the turmoil, foreigners were expelled and Cambodians sought refuge in camps in Thailand. In 1979, Pascal Grellety returned to Cambodia to rebuild a medical centre and coordinate health aid.

Ten years later, in 1989, Sylvie Léget also went to Cambodia with the ICRC. Her assignment lasted five weeks, including two spent on the Thai border, and left a lasting mark on her. “When I arrived, it seemed like we were almost the only humanitarian organization there. There was UNICEF, probably MSF, maybe some others, but only a few,” she said. According to Léget, there was significant need for humanitarian aid and the ICRC, far from having left Cambodians to fend for themselves, remained active in the country.

Ampil, Site 2. ICRC Tracing Agency office. S. Léget, 1989. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-TH-D-00114-09.

She recalled, “That period followed the Khmer Rouge and the intervention of the Vietnamese. Several hundred Cambodians had gone to camps on the Thai side. Hostilities hadn’t really stopped, and there was a huge influx of people who had been displaced returning. We knew the ICRC was receiving media requests, and the ICRC wanted first-hand information. At the time, information didn’t travel as quickly as it does today.

“I had the chance to go to Cambodia, and then to the Thai border from Bangkok to visit camps. It was rather unusual – normally you can’t visit them. I had the opportunity to work for the Central Tracing Agency. I accompanied someone from the Cambodian Red Cross Society who was doing tracing work in Phnom Penh and the provinces. We tried to find people’s family members who had fled when people were displaced. It was my first field mission. We were able to find two families, and I was responsible for delivering the news in the camp. I got to tell people that their loved ones were still alive.”

Chhouk, Kampot province. A woman looks at photos her sister sent from the Site 2 refugee camp. S. Léget, 1989. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00036-05.

ICRC staff continued their work and did not stray from the rules that all inhabitants in the country had to follow. “There was a very early curfew, and you needed permission from the authorities to move about the provinces,” said Léget. “One thing I remember striking me was that the ICRC would send a courier to request permission to change locations. Freedom of movement was restricted, even for Cambodians.”

Site 8 refugee camp. Rice is distributed to Cambodian refugees. S. Léget, 1989. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-TH-D-00115-08.

She continued, “It was my first assignment, but I feel that the experience lives on in me. I keep looking for archival sources and trying to understand what really happened at the time. It’s important to talk about it. There are the families of all the people who died under a reign of terror. We can’t forget – we have to learn from history. I feel as though this chapter isn’t entirely closed. It’s a tragedy that has left its mark, and we have to go beyond the superficial and find those traces, to commemorate and really understand what humanity is capable of.”

Kampot. A young man who had his foot amputated after a mine injury. S. Léget, 1989. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00037-09.

The ICRC’s audiovisual archives are full of photographs from the period. Léget also discussed her role as a photographer for the ICRC; she was deeply affected by what she witnessed and photographed during her time in Cambodia:

“The goal was to show the ICRC’s humanitarian work. Now, would we do it differently? Perhaps we ask ourselves more questions, particularly about the photographer’s position in relation to the victim.

“To me, nowadays, there are too many images – it’s less interesting. All you have to do is look at your phone for a photo to be in your face. At the time, the process of looking at an image was more deliberate. We don’t take the time anymore.

“There’s a difference between a photographer with a professional approach that’s thoughtful and constructed and someone who takes their phone out to take a snapshot. There’s a whole element of staging. At the time, we didn’t really think about that. There weren’t even ICRC delegates in charge of communications. If I recall, that only really started with Rwanda. Before that, there were no delegates whose role was to spend time with the people being photographed.”[28]

Conclusion

Phnom Penh, ICRC delegation. Central Tracing Agency office and files. M. Mercier, February 1975. ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00000-03.

The tragic events in Cambodia have left their mark. For the ICRC, the impossibility of engaging in dialogue with the Khmer Rouge, the unpredictability of the decision-making and the general uncertainty made the organization’s work extremely difficult.

Today, the ICRC continues to carry out a wide range of humanitarian work in the country, in particular to help displaced people and, since the 1990s, to help victims of landmines. According to a report by Greenberg Research, local communities see the ICRC favourably, in particular thanks to the work of the Central Tracing Agency, which opened in March 1976 and has been a precious resource for many Cambodians whose loved ones have gone missing.[29]

Could the ICRC have done things differently during the fall of Phnom Penh in April 1975? Peter Kunz said no: “We didn’t know what we were getting into. François Perez had left the delegation amid a relatively peaceful atmosphere. We had no idea what was going to happen to us. André [Pasquier] had to learn a lot on the job and improvise as he went.

Sylvie Léget added, “The ICRC played a central role [in events]. I also listened to the interview with Pasquier, which I found very moving. … In April 1975, the French embassy was the only Western diplomatic presence still there. To me, they were heroes. I have immense admiration for those who chose to stay until the very end. I’ve also been trying to understand what went on inside the embassy, but there’s nothing – it’s nearly impossible to find answers. The more you dig, the more you realize how complex the situation was – evidence was erased or hidden or altered. It’s incredibly difficult to piece together what really happened.”

Bibliography

Bizot, F., Le Portail, Versilio, Paris, 2014.

Grellety-Bosviel, P., and Bocquillon, S., Toute une Vie d’Humanitaire: 50 Ans de Terrain d’un Médecin-Carnettiste, Elytis, Bordeaux, 2013.

Pasquier, A., Chronique Commémorative de ma Mission au Cambodge: Janvier–Mai 1975, April 2015.

Ponchaud, F., Cambodge, Année Zéro, Kailash, Paris, 1998.

ICRC Archives

ACICR B AG 063 – 424.02, “Polémique avec un journaliste – ‘L’incident est clos’”, Journal de Genève, 15 May 1975.

ACICR B AG 063 – 424.03, 424.03, excerpt from a press conference by Pasquier and Grellety on the ICRC’s activities at the time of the capture of Phnom Penh.

ACICR B AG 063-424, Bruggmann, A., “Encore un faux débat”, La Tribune de Genève, 14 May 1975.

ACICR B AG 063 – 424.02, “Red Cross refutes Cambodia criticism from Vany Walker-Leigh”, The Guardian, 13 May 1975.

ACICR B AG 203 042.001-02, press release No. 1226, “Phnom Penh: Zone sanitaire et de sécurité établie par le CICR”, 16 April 1975.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Léget, S., “Chhouk, Kampot Province. A woman looking after the photos sent by her sister from the refugee camp of Site 2”, 1989, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00036-05: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/63772.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Léget, S., “Kampot. A young amputated man wounded by a mine”, 1989, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00037-09: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/63780.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Mercier, M., “Phnom Penh, délégation du CICR. Bureau de l’Agence centrale de recherches et vues des fichiers”, February 1975, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00000-03: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46394.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Zen Ruffinen, F., “Phnom Penh, Le Phnom Hotel. Meeting between two ICRC delegates and a member of GRUNK armed Forces after the fall of the capital”, 17 April 1975, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00008-04: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46495.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Mercier, M., “Phnom Penh. Crown [sic] in front of Le Phnom Hotel neutralized by ICRC”, February 1975, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00008-03: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46494.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Mercier, M., “Phnom Penh. Le Phnom Hotel neutralised by ICRC”, February 1975, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00008-02: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46493.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Mercier, M., “Phnom Penh. Street scene”, 1975, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00003-01: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46433.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Vaterlaus, M., “Phnom Penh. Khmer Red Cross tracing service”, March 1973, reference No. V-P-KH-D-00001-21: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46416.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, “Phnom-Penh, ICRC delegation headquarters. An ICRC delegate speaking during delivery of ICRC donations: 99 boxes with medicines and 593 boxes with milk to Khmer Red Cross”, 5 April 1973, reference No. V-P-KH-E-00192: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/118158.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, “Phonm-Penh. Refugees at the French Embassy”, April 1975, reference No. V-P-KH-E-00085: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/73329.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, “Battambang province, Beng-Khtum. Princesse Neak Moneang Monique Sihanouk, Cambodian Red Cross President, distributing relief assistance to internally displaced persons”, 23 December 1968, reference No. V-P-KH-E-00066: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46646.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Léget, S., “Site 8, refugee camp. Distribution of rice for Khmer refugees”, 1989, reference No. V-P-TH-D-00115-08: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/88065.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, “Interviews au Cambodge”, 16 February 1975, reference No. V-S-10265-A-13: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Sound/7818.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, “ Mission au Cambodge”, 11 February 1974, reference No. V-S-10053-A-03: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Sound/6787.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Léget, S., “Site 2, Ampil. ICRC Central Tracing Agency office”, 1989, reference No. V-P-TH-D-00114-09: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/88063.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Vaterlaus, M., “Ta Khmao, Vat Prèk Reussey. Distribution by Khmer Red Crosas [sic] of basic relief items to displaced persons”, March 1973, reference No. V-P-KH-E-00047: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Picture/46628.

ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Vers des jours meilleurs, 1973, reference No. V-F-CR-H-00142: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Film/5568.

Interviews

Interview with Sylvie Léget, 19 February 2025.

Interview with Peter Kunz, 6 March 2025.

Footnotes

[1] “Of the twenty-eight foreigners who remained at the delegation after the Swiss and Swedish medical teams left, fourteen decided to stay.” A. Pasquier, Chronique Commémorative de ma Mission au Cambodge: Janvier–Mai 1975, 2015, p. 37, translated. Freely available from the ICRC Library website: https://library.icrc.org/library/search/notice?noticeNr=42842

[2] Idem.

[3] Idem, p. 4.

[4] Pasquier, p. 14.

[5] ICRC Audiovisual Archives, Interviews au Cambodge, 16 February 1975, reference No. V-S-10265-A-13: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Sound/7818.

[6] Idem.

[7] PASQUIER, André. Chronique commémorative de ma mission au Cambodge: janvier-mai 1975, avril 2015, p. 14.

[8] Idem, p. 31.

[9] Between 1973 and 1998, the Executive Board was a “collegial body… responsible for the general conduct of affairs … [exercising] direct supervision over the administration of the ICRC”. Definition from the New Statutes of the International Committee of the Red Cross, published in: International Review of the Red Cross, No. 149, August 1973, p. 427: https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/new-statutes-international-committee-red-cross.

[10] Pasquier. p. 33.

[11] Pasquier, p. 36.

[12] Interview with Peter Kunz, 6 March 2025.

[13] ICRC Archives (ACICR) B AG 063 – 424.03, excerpt from a press conference by Pasquier and Grellety on the ICRC’s activities at the time of the capture of Phnom Penh.

[14] “The Red Cross did not think that the fact that it had agreed to transmit the Long Boret Government’s offer of surrender to the Khmer rouge had affected its position, claiming that the policy of the new authorities was to expel all foreigners, including United Nations employees.”

ACICR B AG 063-424.02, “Red Cross refutes Cambodia criticism from Vany Walker-Leigh”, The Guardian, 13 May 1975.

[15] Pasquier, p. 53.

[16] Pasquier writes: “On the whole, our initiative was well received, except for two journalists, Tolgraven and Fröhder. ‘Creating this zone, with its limited capacity,’ they said, ‘makes no sense in a city with two million inhabitants, all the more so given that you have no guarantee that the Khmer Rouge will respect it.’ ‘You tell us,’ said Fröhder wryly, ‘that it’s a demilitarized area. Very well, go ahead and tell the armed and uniformed captain and soldier sitting at the bar next to the pool to leave the premises immediately!’” Idem, p. 51.

[17] Pasquier writes: “Their expressions were closed-off and hard. The mood shifted in an instant. Their weathered, tired faces betrayed no joy, no smiles, no hint of triumph.” Pasquier, p. 57.

[18] Interview with Peter Kunz, 6 March 2025.

[19] Article 15, on neutralized zones, states: “Any Party to the conflict may, either direct or through a neutral State or some humanitarian organization, propose to the adverse Party to establish, in the regions where fighting is taking place, neutralized zones intended to shelter from the effects of war the following persons, without distinction: a) wounded and sick combatants or non-combatants; b) civilian persons who take no part in hostilities, and who, while they reside in the zones, perform no work of a military character.”

Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Geneva, August 12, 1949.

[20] ACICR B AG 063 – 424.03, p. 7.

[21] Pasquier, p. 63.

[22] F. Ponchaud, Cambodge, Année Zéro, Kailash, Paris, 1998, p. 18, translated.

[23] Pasquier writes: “None of our cars were permitted on the embassy premises, and we were forbidden from displaying the red cross emblem and doing any humanitarian work there. In short, we were tolerated only so long as we left the Red Cross at the door.” Pasquier, p. 65.

[24] Interview with Peter Kunz, 6 March 2025.

[25] Idem.

[26] Pasquier, p. 84.

[27] An article in the Journal de Genève states, “The ICRC and Mr. Froehder each maintain their position on how events unfolded in Phnom Penh and consider the discussion closed.” ACICR B AG 063 – 424.02, “Polémique avec un journaliste – ‘L’incident est clos’“, Journal de Genève, 15 May 1975.

[28] For more on the same topic, see Focal Point – A Discussion on Field Photography by Lucie Parrinello: https://avarchives.icrc.org/Film/29673.

[29] The research agency noted: “The role of the ICRC/Red Cross. The ICRC/Red Cross is both well-known and well respected in Cambodia. Furthermore, the organization’s continuing role in helping families trace missing relatives has given it a special standing.” Greenberg Research, People on War: Country Report Cambodia, ICRC, Geneva, 1999: https://library.icrc.org/library/search/notice?noticeNr=16431.

Comments