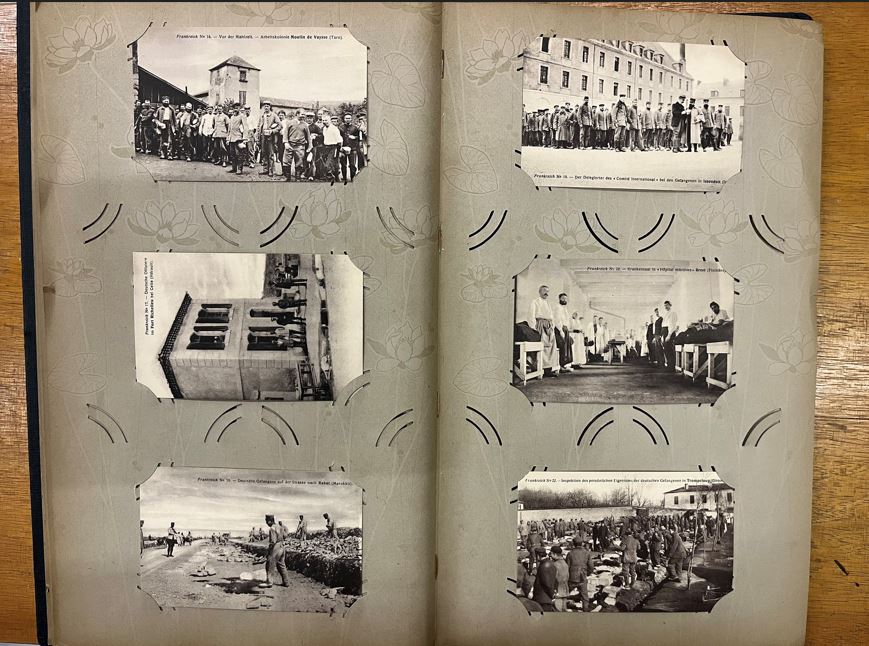

During the First World War, the International Prisoner-of-War Agency (IPWA)[1] of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) published a collection of postcards that depicted what kind of places and what kind of conditions prisoners of war (POWs) and civilian internees were living in.

This clothbound book, preserved in the ICRC’s archives,[2] bears a cover illustration of a young Dutchman smoking a pipe – an image much in fashion at the start of the 20th century. Demonstrating what a singular and ambitious undertaking this initiative was in wartime, the book contained 283 pictures of POW camps in Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Russia and the Ottoman Empire. Most of the postcards, 218 of them, were “official” pictures that had been obtained by 1 September 1916. The remainder was a representative sample of postcards from various English, French and German publishers.[3]

Tens of thousands of copies of these postcards had been produced and sent by the IPWA, between September 1915 and the start of 1917, with the aim of providing the detainees’ families with information. The postcards have recently been digitized, tagged and made available in high definition on the ICRC’s audiovisual archives portal.

Below are some of the key moments and the issues surrounding the publication of the postcards, as well as some thoughts regarding the scenes they depicted, the context in which they were produced, and the ways they were circulated.

Cover and front endpaper of the album containing postcards from the First World War, ACICR V CI 08-046.

First steps

The initiative’s beginnings were somewhat complex. At first, the aim was simply to alleviate some of the suffering of the families of detainees, families who had often heard nothing from their loved ones since they had been captured.[4] Although the impetus for the initiative lay with the IPWA, the talks that were needed to get the go-ahead from the civilian and military authorities of the countries involved quickly got bogged down. It is highly likely that for the parties to the conflict this was an opportunity for a diplomatic coup by showing that the POWs in their power were being treated absolutely in accordance with the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the Geneva Convention of 1906.

From the outset, there were two opposing approaches: for the French minister of war, enough photographs had already been taken by the ICRC delegate Carle de Marval when he visited German POWs in January and February 1915;[5] for his German counterpart, several new series were needed.[6] In an attempt to settle the matter, the ICRC showed the French the photographs taken by the Germans at Döberitz so that the amateurism of Marval’s work would become clear.[7] While it is no longer possible to say which photographs were taken by Marval, there is no doubt that the ICRC at the time wanted to make sure, in advance, that it could not be accused of playing into the hands of German propaganda.

In November 1915, the IPWA sent its first postcards from the German camps to the French Red Cross, giving the scenes shot in Darmstadt and Stuttgart as examples and requesting similar photographs of the French camps.[8] National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies therefore served as intermediaries for their own governments. In France, the ICRC also managed to get postcards of the German camps sent to the Association des Dames françaises[9] – and made sure it was widely publicized, a sign of its desire to cast its net wide to broaden its collection.[10]

Even General Lyautey, France’s resident-general in Morocco, was requested to obtain authentic photographs of the camps (and not reproductions from newspapers).[11] The fact that France’s representative in its Moroccan protectorate was asked shows that the IPWA’s initiative was being taken seriously at the highest levels. To keep the momentum going, Gustave Ador, the ICRC’s president, used his influence to support the initiative while on a trip to Paris, which was well received by the Ministry of War.[12]

At the end of the year, the Ottoman Red Crescent responded positively to the first batch of postcards it received and agreed to take photographs of camps recently set up.[13]

Tiptoeing through a (figurative) minefield

However, the use of postcards at that time could also arouse mistrust. As photography became more and more accessible at the end of the 19th century, the postcard became a means of mass communication that could be used to stoke up patriotism and demonize the enemy in support of the war effort. As a result, the IPWA faced a major difficulty: it needed to persuade, via the National Societies, that the initiative’s success depended on all the parties to the conflict giving permission for photographs of their camps to be taken and sent abroad.

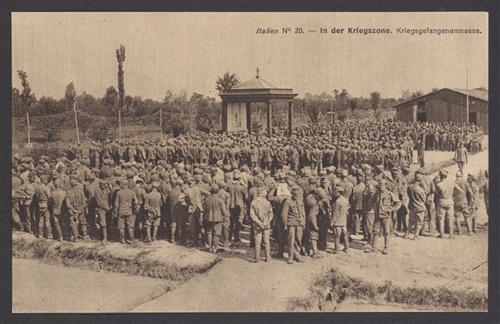

First World War, 1914–1918. Prisoner-of-war camp in Italy, where most of the prisoners are photographed from the back, © ICRC, V-P-HIST-04290.

When the Italian Red Cross received a batch of postcards from the IPWA, it said at first that the Italian government did not want photographs to be taken of the POWs in camps under their authority out of “respect for the prisoners”.[14] Adolphe d’Espine, the ICRC’s vice-president, explained that the goal was not to be able to distinguish between the prisoners individually but rather to know what their living conditions were like in the camps. He put the problem in stark terms: the Italians should reciprocate and provide photographs of their camps or the Austrians would not likely continue to allow the families of Italian POWs to have photographs of the Austrian camps.[15] Although it is hard to know whether a kind of opportunism or this argument weighed more, in the end, in March 1916, the Italian Red Cross informed the IPWA that the Italian government had reversed its decision and now agreed to have camps on its territory photographed, provided that the prisoners, if they so wished, did not appear in them.[16]

After receiving a batch of postcards, probably depicting the German and French camps, the Russian Red Cross Society informed the ICRC in May 1916 that the Russian army’s general staff were refusing to contribute to the IPWA’s initiative.[17] Russia seemed reluctant to promote exchanges of this kind with Germany, which had, with the help of Austria-Hungary, inflicted severe defeats on the tsar’s forces in Galicia, Poland, Lithuania and Courland, forcing the imperial army to retreat in drastically reduced numbers. Japan, however, an ally of circumstance until the end of the tsarist regime, received photographs of the camps that were under Russian authority via the Japanese Red Cross Society.[18]

During the terrible fighting to capture Mort-Homme (“Dead Man’s Hill”) during the Battle of Verdun, the tensions between France and Germany were palpable. The IPWA feared the effect of a preface Dr Backhaus had written in a book[19] in which he insulted the French, calling them “scoundrels”. The book contained many photographs of German camps.[20] Shortly afterwards, General Brochin, commander of France’s seventh military region, banned the public exhibition and sale of these postcards on the ground that they could “mislead public opinion” as to the genuine living conditions of POWs in Germany.[21]

French customs officers reportedly also seized several batches of postcards, hindering their circulation, which triggered a complaint by the ICRC to the French embassy in Bern in early 1917. There was no doubt any longer about the importance attached to this type of communication in wartime.

A real success

The postcards also gave rise to a form of enthusiasm for what the IPWA was doing. The press began to speak about it; Le Gaulois, for instance, as early as December 1915 wrote that it was a matter of “responding to the often expressed wishes of the families of soldiers taken prisoner in the belligerent countries.”[22]

The following year, the art historian Pierre-Marcel Lévi, director of the photographic section of the French Ministry of War, suggested reproducing photographs of the IPWA’s activities in Geneva to supplement photographs taken in French camps for a forthcoming book. To achieve this, the ICRC commissioned two well-known Swiss photographers, Frédéric Boissonnas and Rodolphe Gilli, who had already taken many photographs of the IPWA’s work in the Rath Museum.[23] Through these new photographs, they succeeded in creating – perhaps for the first time – a visual connection between the POW camps and the painstaking work of the IPWA.

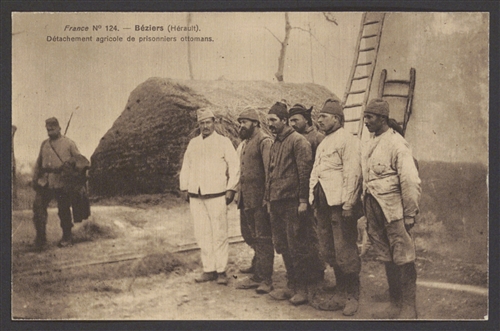

The postcards also seem to have been used as bargaining chips for information. This was the case with the Ottoman Red Crescent, which was asked to provide images of the graves of English and French soldiers killed at Gallipoli in exchange for photographs of the camp at Béziers.[24] In one sense, this was an early sign of a desire to use photography for the purpose of identifying the dead, whose rules were codified internationally for the first time in 1929.[25]

First World War, 1914–1918. Hérault, Béziers, prisoner-of-war camp. Agricultural detachment of Ottoman prisoners, © ICRC, V-P-HIST-04262.

In 1917, la Croix jaune (“the Yellow Cross”), an association that looked for people who had gone missing in the war, suggested an exhibition of the photographs should be held in Paris. Among other arguments put forward was the fact that the photographs of German camps provided by the ICRC, in particular during visits by the organization’s delegates, could not be suspected of betraying reality, unlike those published by Germany. The chair of this modest association, who himself had heard nothing from his son since 1914, highlighted another, cruelly realistic, motivation: displaying the photographs would dispel the false hope harboured by some families who mistakenly believed they could recognize their loved ones.[26]

Surprising compositions

Beyond the intentions behind the distribution of the postcards and the methods for publishing them, it is hard not to be struck by some of the scenes of civilian and military detention that they depict, which were staged most of the time. Here are some of the most striking features:

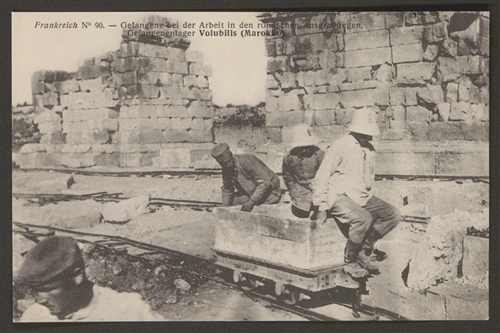

- The kind of work the detainees were assigned to – roofing, gardening, archaeological digs, hairdressing, building railways and even working in a bakery. This, often forced, labour met practical needs, but was also a reflection of the functional organization of the camps.

- The many recreational, intellectual and spiritual activities. POWs were able to take part in sports and musical or artistic activities like painting and drama, as well as religious services, which demonstrated a certain effort to maintain a social and cultural life in captivity.

- The types of places of detention. Some camps were set up in châteaux, citadels or even educational facilities that had been requisitioned, such as schools. The choice of location reflected both logistical constraints and the need to segregate POWs on the basis of their rank or status.

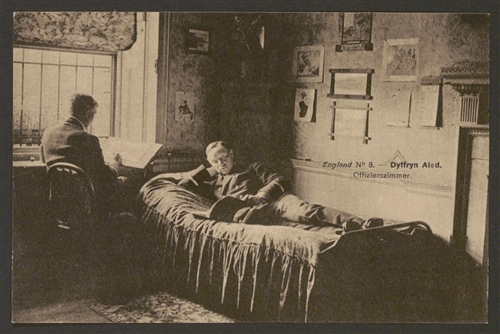

- The striking degree of comfort enjoyed by officers compared to the rank and file. Officers often had their own bedrooms and the furniture was rudimentary but tailored to their needs, whereas non-commissioned soldiers were often kept together in cramped huts.

- The presence of journalists from neutral countries during official visits, in particular visits by delegates from the Triple Alliance and the ICRC, highlight the desire to ensure – or at least give the impression of – a certain transparency with regard to detainees’ living conditions.

- The relative absence of photos from camps reserved for civilian internees among the postcards. The explanation for this lack of balance may be the legal uncertainty surrounding the status of civilian internees in international treaty law, the sheer lack of visits carried out in civilian places of detention or the fact that publishing images of civilians was much less interesting from a propaganda point of view compared with images of POWs.

- Gustave Ador, ICRC president, appeared on at least one of the postcards (the château de Chadrac). It is probably the oldest photograph of an ICRC president visiting a place of detention, giving it documentative and historical value.

It should be underlined that during the First World War, POWs were not explicitly protected by law against public curiosity. With the benefit of hindsight, this can look like a serious shortcoming in terms of protecting POWs’ private lives. This shortcoming would be partially remediated in 1929 with the adoption of the Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, which explicitly states that POWs must be protected against public curiosity.[27] This form of protection would be strengthened in the Geneva Conventions of 1949 in response to the abuses recorded during the Second World War.[28] As a result, the photographs taken in the First World War that enabled POWs to be identified should be understood from the point of view of the legal norms of the time.[29]

Conclusion

Any humanitarian action carried out by the ICRC involves a form of, often arduous, negotiation with parties to a conflict. The publication of these postcards during the First World War was no exception. The IPWA therefore had to deal with long and complex negotiations in order to constitute a collection that, far from being knocked out overnight, was gradually built up during the war, with the help of the National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

The 283 postcards kept in the ICRC’s archives are documents that are likely to be of interest to anyone wishing to have a visual trace of the work carried out by the detainees, the huts they lived in, the officers’ accommodation or the sites and infrastructure used to hold detainees during the Great War. They are also an invaluable resource to see the cultural and religious constructions they made, the natural environments they operated in (seafronts, deserts, mid-range mountains, etc.) and some archaeological remains. In addition, these postcards are the product of their designers’ original intentions, serving as a source of information for detainees’ families, albeit, inevitably, instrumentalized for wartime propaganda.

Alongside the other postcards from the First World War that the ICRC holds originals or reproductions of, this collection of postcards would benefit from a thorough historical and iconographical study in light of its significance for the organization and the families of POWs more than a century ago.

Find out more about the ICRC’s work during the First World War:

The ICRC vs fake news: Setting the record straight in the First World War

World War 1914–1918: Reports on the visits of the prisoners of war camps

[1] Set up by the ICRC in August 1914, the IPWA’s mission was to restore contact between detainees (in particular, prisoners of war and civilian internees) and their families by collecting, centralizing and forwarding information on and to them.

[2] ICRC Archives, V CI 08-46.

[3] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, Catalogues 20 December 1915–10 April 1919.

[4] To provide information that could be of interest to families of combatants, from January 1916 the ICRC published a weekly pamphlet called Nouvelles de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre (“News from the International Prisoner of War Agency”). These pamphlets, which cover the publication of the postcards, can be consulted via the ICRC library catalogue: https://library.icrc.org/library/search/notice?noticeNr=P00198

[5] See report in ICRC Archives (C G1 A 19-01.01), available in French only: https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/en/Camps/Zossen/451/en/

[6] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the French minister of war, dated 28 August 1915, and letter from the ICRC/IPWA, dated 7 October 1915.

[7] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the ICRC/IPWA, dated 7 October 1915.

[8] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the IPWA, dated 26 November 1915.

[9] One of the three branches of the French Red Cross, this association was formed to provide medical assistance to the army and navy in wartime, and to train women nurses and ambulance drivers. See (in French only): https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/S1816968600001456a.pdf

[10] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the ICRC/IPWA, dated 3 February 1916 and letter from the Association des Dames françaises, dated 14 February 1916.

[11] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter dated 2 December 1915 (sender unknown, believed to be related to General Lyautey by blood or by marriage, whom he addresses as “My dear cousin”).

[12] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from French minister of war, dated 6 December 1915.

[13] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from Ottoman Red Crescent, dated 11 December 1915.

[14] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the Italian Red Cross, dated 7 December 1915.

[15] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the ICRC/IPWA (F. Barbey), dated 16 December 1915.

[16] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the Italian Red Cross, dated 25 March 1916.

[17] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the Russian Red Cross Society, dated 2 May 1916.

[18] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the Japanese Red Cross Society, dated 13 April 1916.

[19] Alexander Backhaus, scientist and university lecturer specializing in agronomy, regarded as a polemicist by the French government, wrote the preface to a work on the food given to POWs in the German Empire. To consult the work in question, go to: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10315935d

[20] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, handwritten note in letter from the ICRC/IPWA (F. Barbey), dated 6 March 1916 ; the word canaille (“scoundrel”) appears on p. 23, available here: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10315935d/f39.item

[21] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from General Brochin, dated 24 May 1916.

[22] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, press cutting of 20 December 1915.

[23] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the ICRC/IPWA, dated 11 March 1916.

[24] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the ICRC/IPWA, dated 22 January 1917.

[25] In particular, the Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field of 27 July 1929.

[26] ICRC Archives, C G1 A 06-04, letter from the Croix jaune, dated 23 November 1917.

[27] Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of 27 July 1929, Article 2.

[28] Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of 12 August 1949, Article 13.

[29] For more information about the issue of public curiosity, see Michael A. Meyer and Risius Gordon, “The protection of prisoners of war against insults and public curiosity”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 33, No. 295, August 1993, pp. 288–299.

Comments