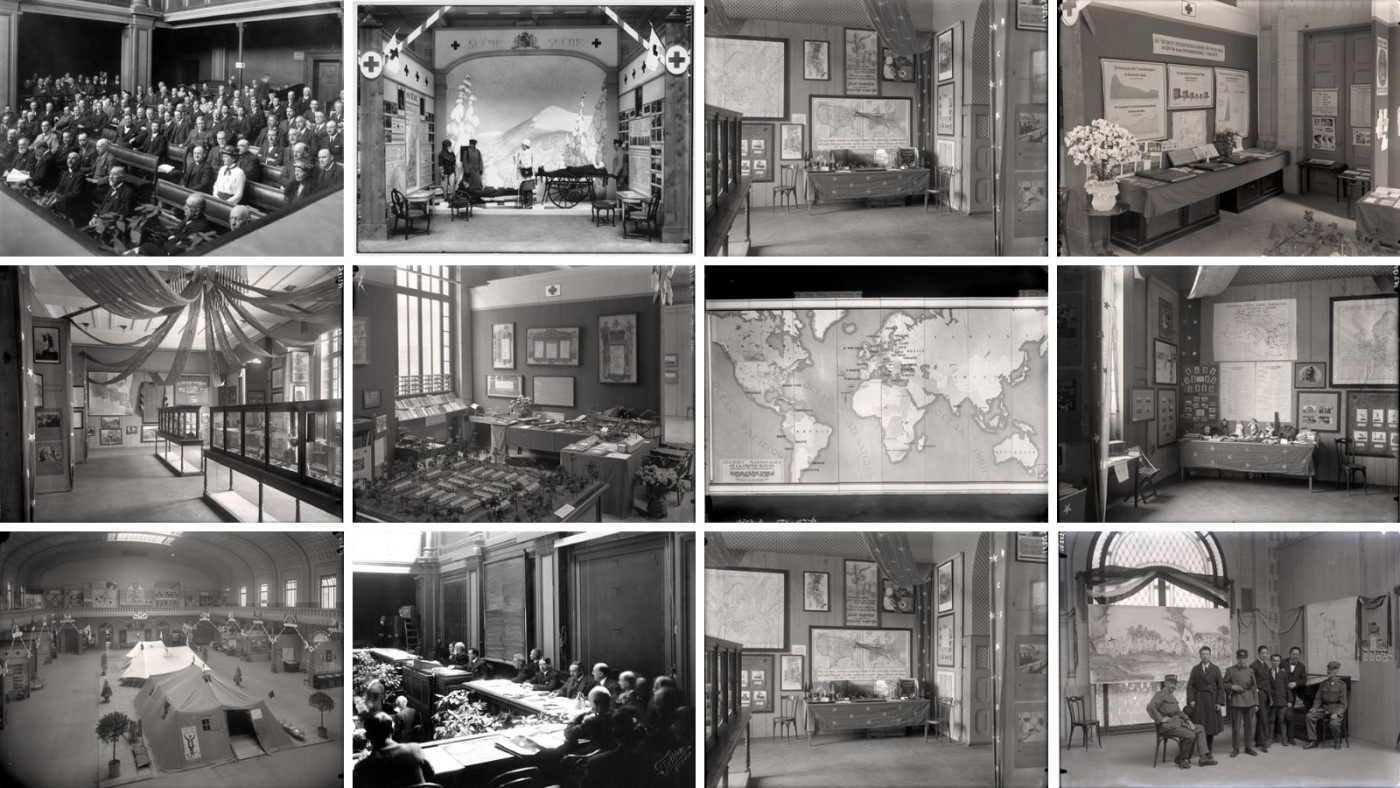

The 10th International Conference of the Red Cross opened in Geneva on March 30th, 1921. Convened by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Conference brought together delegates from the National Societies of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (the Movement) and from States parties to the Geneva Conventions, after a decade-long hiatus. Since the last edition, hosted in 1912 by the American Red Cross in Washington, the experience of WWI had triggered important developments within the Movement – including the recruitment of many new volunteers and the foundation of new National Societies. Through the action of its International Prisoners of War Agency, the ICRC had become a fully operational international relief organization. Now that the war was over, its attention also returned to the development of international humanitarian law: the global conflict had brought to light both the importance and the shortcomings of the Geneva Conventions in force at the time.

The stakes of the Conference were high for the ICRC. Bringing the former warring powers to the table, it aimed to develop the international legal regime protecting war victims and to reaffirm the universality and cohesion of the Movement. It had also become quite urgent to formalize its action in peacetime and the prerogatives of its different actors. The League of Red Cross Societies, a somewhat inconvenient newcomer within the Movement in the ICRC’s eyes, had been founded two years earlier by the National Societies of the victorious countries. And, while the humanitarian field was getting more crowded, the needs were certainly not diminishing, especially in Central and Eastern European countries stricken by famine and epidemics.

This article draws on sources from the ICRC’s various archives and library collections related to the 1921 International Conference – including the first ICRC films – and invites the reader to (re)discover some of the actors and stakes of this turning point in Red Cross history, a century later.

Words and footage

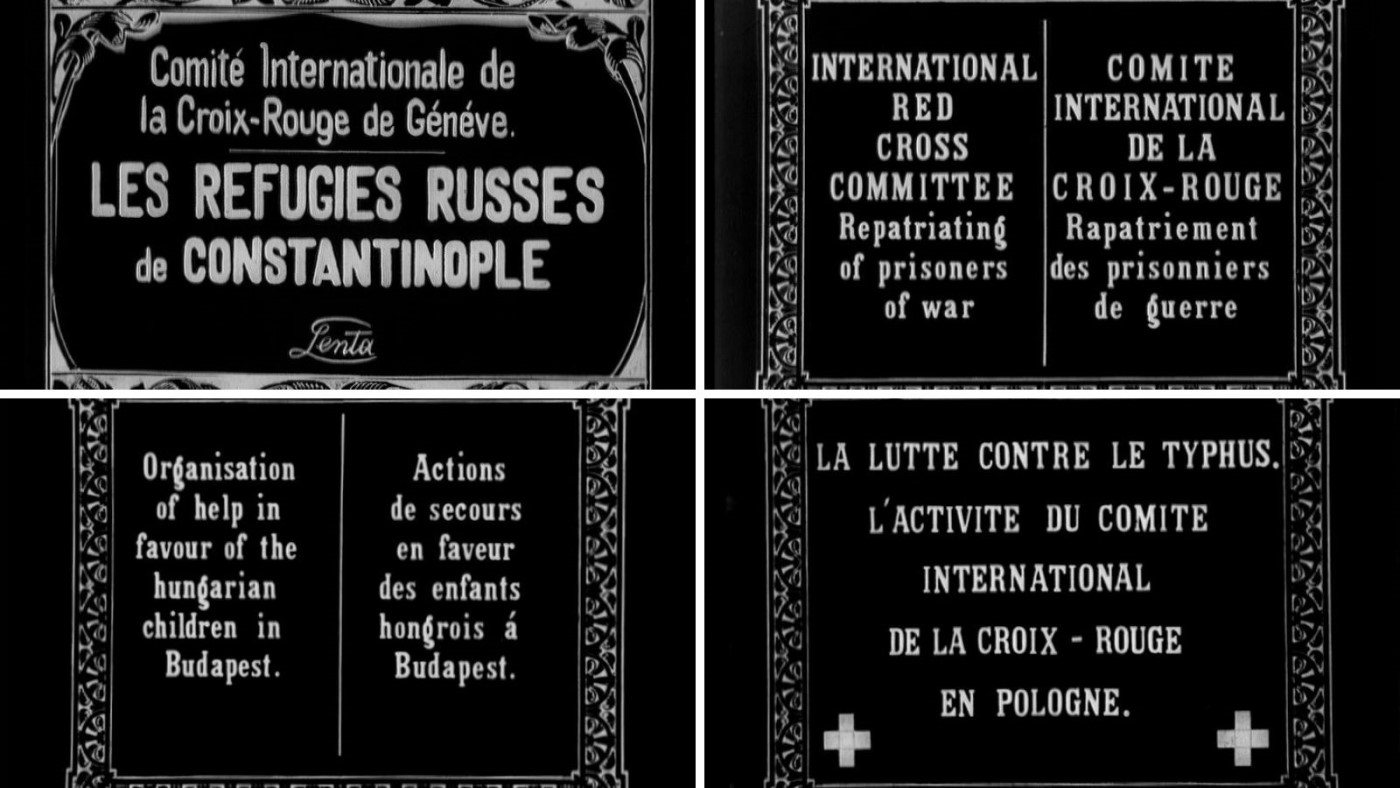

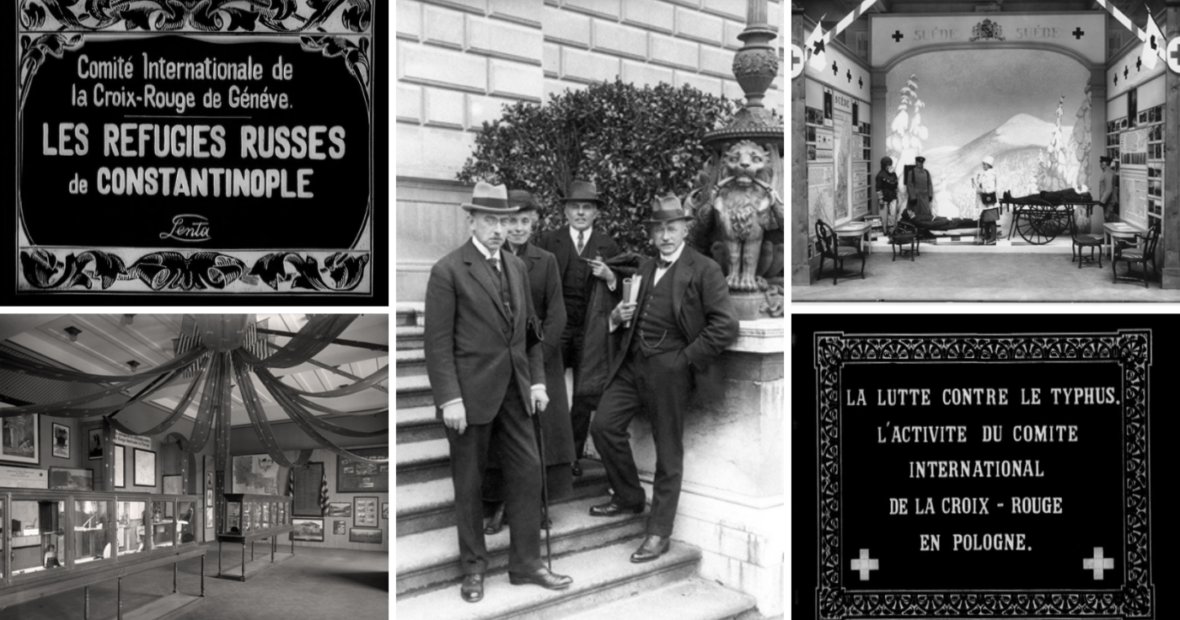

At the beginning of 1921, showing a real innovative spirit – let us remember that cinema was still a new art form, a mere twenty-five-year-old invention – the Committee commissioned four films to be shown at the International Conference to be held in March-April of the same year.

The members of the Committee had clearly understood the potential of cinema as a communication tool. It could be decisive for the success of a campaign aimed at publicizing the ICRC’s activities and reaffirming its central position within the Movement, and more broadly within the post-WWI humanitarian landscape.

Click on the image to see the four films commissioned by the ICRC for the 10th International Conference of the Red Cross

Produced in record time, the four films reflect the ICRC’s activities of the period: the repatriation of prisoners of war across the Baltic Sea, the fight against typhus in Poland, humanitarian aid to Hungarian children in Budapest and Russian refugees in Constantinople. No matter how distant in time, these issues still bear a surprising relevance to our contemporary humanitarian crises.

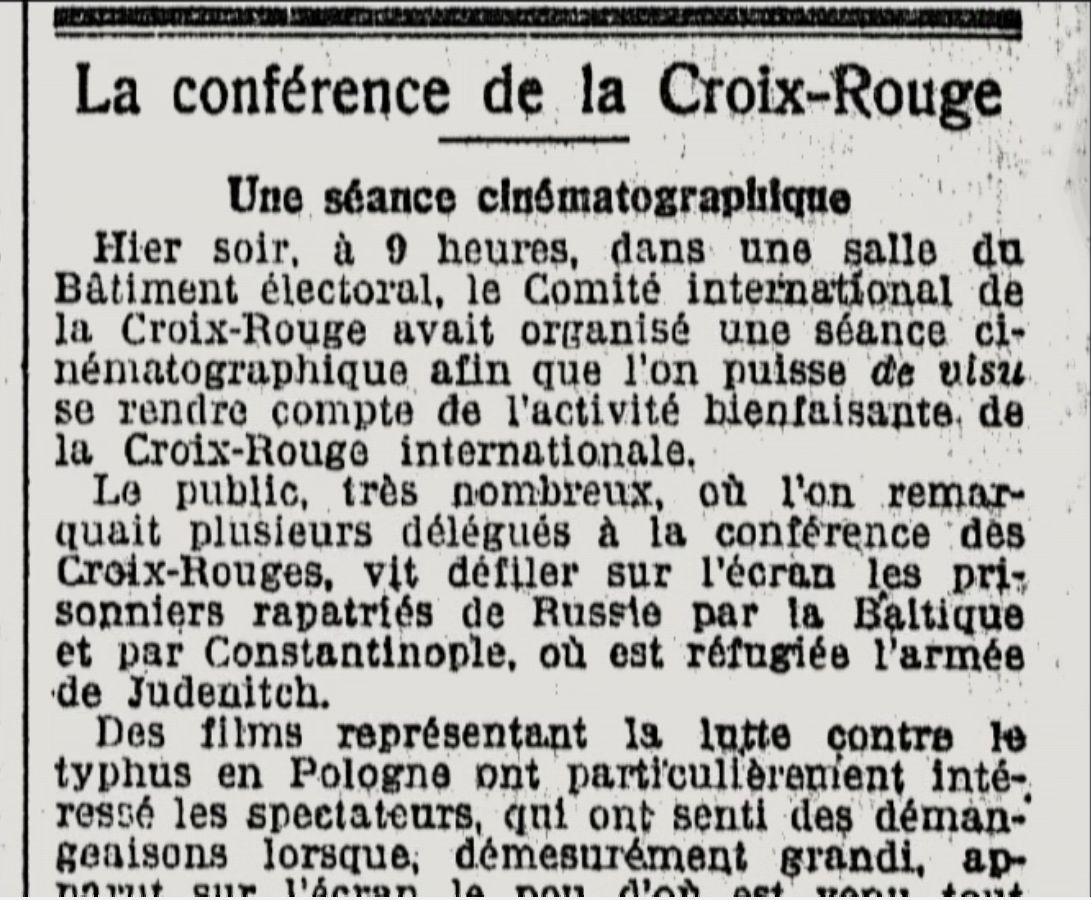

The films’ premiere took place on Saturday, April 2nd, 1921, at 9:00 p.m. in Geneva’s Electoral Building, a stone’s throw from the Place de Neuve. According to reports of the time, the films made a strong impression on the audience, which was largely composed of the participants of the Conference.

This first screening was commented by a delegate, as films were silent at the time, and preceded by a cocktail offered by the ICRC. Though one can only speculate as to the films’ influence on the participants, it is worth already noting that the Conference’s resolutions would prove quite advantageous for the ICRC, as it obtained the recognition of its mandate in peacetime and the confirmation of its prerogatives within the Movement.

For more information: put yourself in the shoes of the 1921 spectators by watching the four first ICRC films, and learn more about their origin with this short documentary (in French).

And in photographs…

« Neither rivalry nor monopoly in the exercise of charity » : relief operations and humanitarian coordination in the post-WWI period

When the date of the long-awaited Conference finally came around, the ICRC – praised for its action during WWI – suffered both from a lack of resources and from competition from the newly founded League of Red Cross Societies. There were talks of ‘internationalizing’ the Swiss organization, including a Swedish project submitted in prevision of the Conference. A wind of change was blowing through the Movement, and members where eagerly waiting to see how responsibilities would be divided between the League and the ICRC. Had the fifty-years-old Geneva-based Committee become obsolete? Not so fast: the ICRC reminded the rest of the Movement of the importance of its neutrality, linked to Swiss neutrality, and how it had enabled its humanitarian action during the war. Behind the scenes, the ICRC and the League negotiated a one-year agreement on their respective mandates. ICRC president Gustave Ador, who also presided over the Conference, shared the good news during the April 1st plenary session: the agreement had been signed. Applause broke out. For the ICRC, the storm had passed. Interventions in its favor, praising its action during the war, followed in rapid succession. Eventually, the Conference’s commission working on the internal organization of the Movement, on which sat the presidents of the most influential National Societies, delivered in its report a vote of confidence in the ICRC. The proposed changes in its composition or prerogatives were rejected, and its mandate in peacetime was re-affirmed. The Conference “expresse[d] the wish that [the ICRC] be sufficiently funded to be able to continue its work“, including by the National Societies. Perhaps the circumstances were right for this outcome: the ICRC, as the host and conductor of the Conference, certainly had the ‘home advantage’.

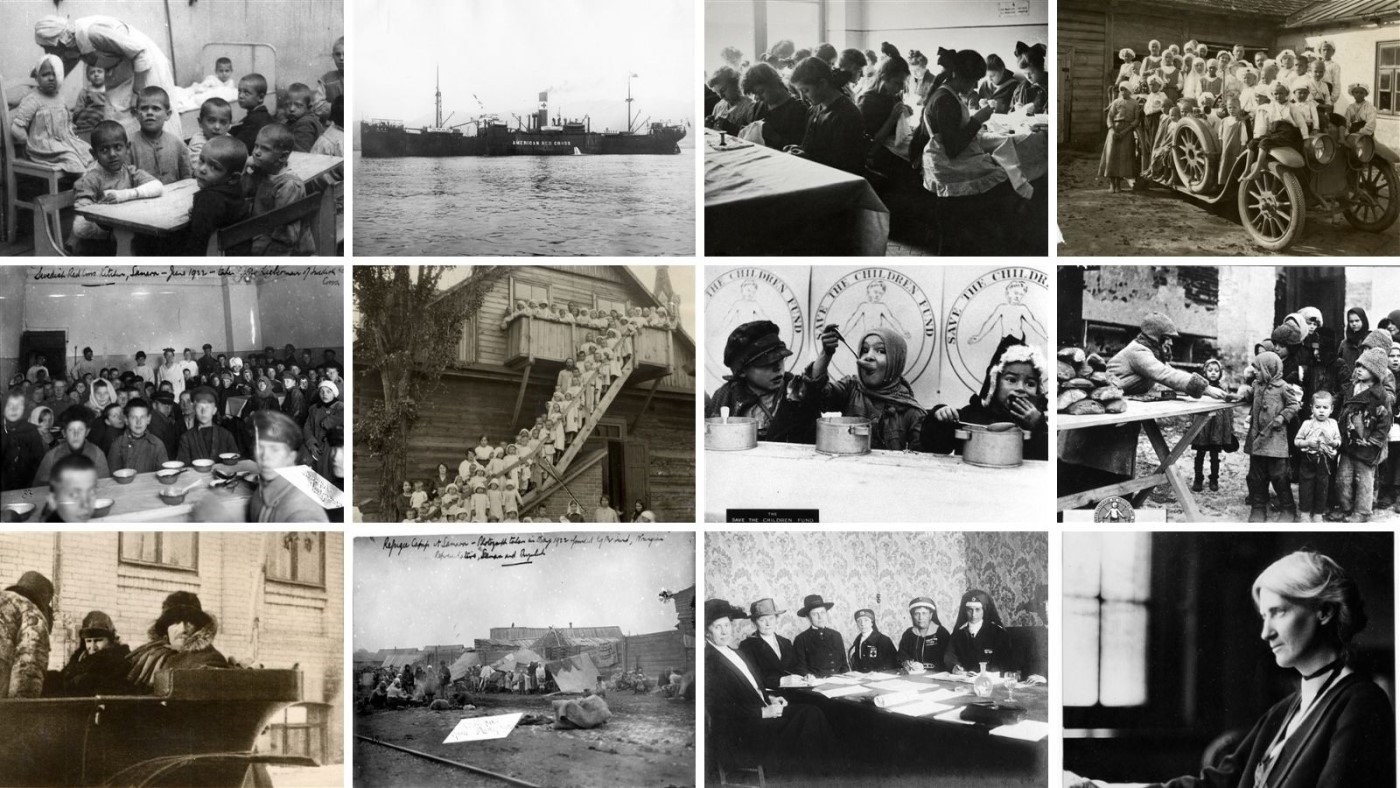

And there was room for the newcomers: the ICRC was rarely represented acting alone in the films it presented to the participants of the Conference. On the contrary, it chose to highlight joint relief actions in the films, showing how it worked hand in hand with the International Save the Children Union, the League of Nations, the American Red Cross and other National Societies.

There was little division among Conference participants on the issue of coordination with humanitarian and international organizations outside of the Movement. A clear consensus emerged on the need to seek the support of the League of Nations and to work together with other relief societies.

Some were actually invited to the Conference as guests, like Eglantyne Jebb, who had founded the International Save the Children Union a year prior with the ICRC’s blessing. Here, cooperation had already been established; ICRC delegates in Central Europe were distributing the relief supplies collected by the International Save the Children Union.

At the end of the discussions, it was agreed that “the Red Cross, by virtue of its essentially humanitarian character, outside of any political, national, social, religious or other preoccupation, was particularly well placed to serve as a center” for all humanitarian action, with improved coordination, as the ICRC had recommended. This responsibility would fall to the National Societies of the Movement at the national level, and to the ICRC and the League at the international level. In the ICRC’s case, this resolution was notably reflected in its collaboration with Fridtjof Nansen of the League of Nations during the 1920s, for the repatriation of former prisoners of war, assistance to refugees and famine relief operations in Russia.

Regulating the extraterritorial activities of National Societies was a thornier issue. Certain societies, like the American, Italian and Greek Red Cross, had developed a strong presence abroad, which caused some tension.

The relations between a country’s Red Cross society and the sections of foreign Red Cross societies active on its territory could be challenging. Should a National Society’s activities be limited to its own nationals, even on foreign soil, and should it be prevented from fundraising outside of its territory? The report of the Conference’s fourth commission first recommended that a ‘foreign’ Red Cross should only be authorized to act abroad for its own nationals. Mr. Guyot, a representative of the Swiss Red Cross, protested: “What would we think, for example, of a city with a French anti-tuberculosis dispensary for French patients, an Italian dispensary for Italian patients, a German dispensary for German patients, and a Swiss dispensary for Swiss patients?”

Eventually, a less definitive wording appeared in the Conference’s resolution: “No foreign section or delegation (…) should be formed or become active in a foreign country without the authorization of the Central Committee of the National Society and the Central Committee of its country of origin, particularly with regard to the use of the name and sign of the Red Cross. The Central Committees are encouraged to give such approval to the largest extent possible in cases where it is established that the foreign section will work exclusively for its compatriots.”

For more information: find all the digitized documentation of the 1921 International Conference on the organization of the Movement and its action in peacetime.

And in photographs…

The Movement and civil wars: the aftermath of the Russian Revolution

There were three noteworthy absentees at the 1921 International Conference. First, the French and the Belgian Red Cross, who declined the invitation “due to considerations arising from some unclarified political circumstances between their governments and that of Germany,” Gustave Ador told the audience. And then there was the more complex case of the Russian Red Cross. The country’s National Society had been dissolved and re-formed in the aftermath of the 1917 revolution. The former organization was represented at the Conference by Mr. Czamansky and Dr. Lodygensky, invited as guests. As for the new organization, the ‘Red Cross of the Soviets’, Ador announced that it had not followed up on his invitation. A telegram from the Society’s president Dr. Solovieff arrived in the middle of the Conference, bringing the issue back to the table. In his message, Dr. Solovieff complained that he had only been invited in a personal capacity and not as the official representative of the National Society. In response, Ador explained the ICRC’s position to the assembly: normal relations between the International Committee and the Red Cross of the Soviets needed to resume, and its delegates allowed to enter Soviet territory, before it would grant the new Society its official recognition. The Conference’s participants approved, not unsympathetic to the cause of the representatives of the former Russian Red Cross sitting at their side.

Far from being limited to a question of protocol, the situation of the Russian Red Cross impacted the Conference’s debates. Its third commission was indeed tasked with looking into the sensitive question of the role of the Movement in civil wars. The German, Finnish, Polish, Italian, Russian (former organization), Portuguese, and Ukrainian Red Cross and the Ottoman Red Crescent all submitted reports on the issue. In 1912, at the previous International Conference, participants hadn’t been able to reach a consensus on this subject. It remained a thorny problem: states were opposed to any development that might give insurgents on their territory a protection comparable to the one granted to enemy armed forces. The idea of an international legal regime applicable to internal conflicts still had a long way to go. The commission working in parallel on the revision of the Geneva Conventions actually promptly rejected it: “it was recognized that [the extension of the Convention to civil war] was impossible, being a matter of domestic legislation. At most, it could be recommended to states to rule that the Convention was applicable to civil wars on their territories. This recommendation did not even seem advantageous.”

But the commission debating the Movement’s action in civil wars reached a more progressive conclusion, even if it worded its recommendations with extreme caution. “The intervention of a foreign Red Cross Society or of the ICRC in times of civil war is an extremely complex, delicate and perilous problem”, said its rapporteur. The ICRC – certainly no longer seen as dispensable at this stage – was entrusted with a new mandate: it was tasked with assisting the National Society thrown in the throes of a civil war if it became unable to meet all the humanitarian needs on its own, and of taking over completely in the case of its dissolution. In 1936, when the Spanish Civil War broke out, it was on the basis of this resolution that the ICRC was able to intervene.

This step forward is certainly not unrelated to the convincing plea of Mr. Lodygensky of the former Russian Red Cross. He was also at first successful in getting the audience to adopt a resolution stipulating, among other dispositions, that “political prisoners in time of civil war must be considered and treated by the belligerent parties as prisoners of war.” At the request of the German, Finnish, Swedish, Swiss and Latvian delegations, this wording was however revised the next day. The final resolution stated instead that “political prisoners in time of civil war shall be considered and treated in accordance with the principles which inspired the drafters of the Hague Convention of 1907.”

For more information: find all the digitized documentation of the 1921 International Conference on civil wars.

Paving the way to the 1929 Convention relative to the treatment of prisoners of war

When the participants of the 10th International Conference met in Geneva, the hostilities had been over for almost three years. But not all former prisoners of war had been able to return to their home country. Since 1919, the ICRC had ramped up its efforts to repatriate the thousands of prisoners whose return was not provided for in international agreements. With Fridtjof Nansen, appointed ‘High Commissioner for the Repatriation of Prisoners of War’ by the League of Nations, it organized the transportation of former prisoners across the Baltic Sea. Images of the operation, filmed in Stettin (Germany, today in Poland) and Narva (Estonia), were shown to the participants of the Conference in one of the ICRC’s films.

While the images reminded the spectator that this was an acute issue, the accompanying captions put the emphasis on the duration of the men’s captivity and their delayed return. As WWI dragged on, the ICRC had grown more and more concerned about the dramatic consequences of prolonged captivity on the physical and mental health of prisoners. Limiting the duration of captivity to three years for all prisoners, prohibiting reprisals, preventing ill-treatments: when the war ended, the ICRC started to draft a “code for prisoners of war”, as the first step towards the adoption of a dedicated Convention of international law.

In anticipation of the Conference, this code was published in the International Review of the Red Cross, which then functioned as an information channel for the Movement. The ICRC noted in its preamble that: “Had the war not been prolonged beyond all expectations, (…) [the] insufficiency and fragility of international Conventions would have passed almost unnoticed, and that the urgency of revising their texts – particularly with regard to the treatment of prisoners – would not have been demonstrated as it is today.” In response, the Swedish, German, French, Spanish and Italian National Societies also submitted to the Conference their conclusions on the fate of prisoners of war and their legal protection. The Conference tasked its second commission with examining these texts.

Although it did not prepare the text of the proposed Convention, a task later entrusted to a group of specialists, the second commission endorsed a series of principles for the treatment and protection of prisoners of war. These principles revolved around the respect of the prisoner’s integrity and civil rights, equal treatment and non-discrimination, the prohibition of reprisals and the limitation of the duration of captivity. In this respect, the commission followed closely the ICRC’s proposals. Its report gave the ICRC a key role in the centralization of information and relief for prisoners of war. It also recommended that it serve as a neutral monitoring body to ensure compliance with the future Convention. A Diplomatic Conference would eventually be convened eight years later, turning these principles into law on July 27th, 1929. The Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was the first text of international law in which the name of the ICRC appeared. The Convention gave the ICRC the possibility to oversee the central agency of information regarding prisoners of war to be set up in a neutral country in wartime. It also provided for the ICRC’s ‘good offices’ as a neutral intermediary between belligerents.

For more information: watch this short documentary on the repatriation of prisoners of war and browse the digitized documentation of the 1921 International Conference on the legal protection of prisoners of war.

And in photographs…

And also: easing blockades for food and medicine for children, sick and elderly people, investigating the violations of the Geneva Conventions during WWI, the training of Red Cross nurses… Explore the other themes of the 1921 International Conference through our collection of digitized documents.

A historian’s perspective, by Daniel Palmieri

The 10th International Conference of the Red Cross was a significant event in many respects. To start, it was the first non-political international meeting where the victors and the vanquished of WWI would sit together. Only Belgium and France declined to participate. Then, the Conference was held in Geneva – the birthplace of the Red Cross and of its initiator the ICRC – which had become the “capital of the world” by welcoming the headquarters of the newly founded League of Nations. The Red Cross Conference would thus be mediatized. Finally, it was the first Conference where the ICRC would have to share its privileged position as an actor-observer with a newcomer – and a competitor – in the Red Cross universe: The League of Red Cross Societies.

Cinematic projections also distinguished the Conference from previous editions. And the ICRC presented its very first films to the public on this occasion.

Filming humanitarian operations

Since the end of WWI, the ICRC had been involved in a vast operation to repatriate prisoners of war from the Eastern Font (Russian, Austrian, Hungarian, and German former prisoners of war). To this end, it had for the first time in its history set up delegations in various Eastern European cities and in Constantinople. This permanent presence on the ground would allow the ICRC to document precisely both the situation and its humanitarian response. Seizing this opportunity, it sent its delegates in Narva (Estonia), Budapest, Warsaw and Constantinople a request to have the institution’s activities in the different contexts captured on film. The resulting production was screened at the International Conference.

From the outset it should be noted that these documentaries would certainly have been produced even in the absence of the Conference. They were part of a more general effort by the ICRC to get known by the general public, especially in Switzerland. A ‘commission in charge of propaganda’ (aka communication) had been created within the institution at the end of WWI for that purpose. It planned on using press and cinema extensively to garner public sympathy and funds. The public was in fact then largely unaware of the ICRC’s action in the troubled post-war Europe. It also tended to confuse the more than fifty-year-old institution with the very young League of Red Cross Societies, founded in 1919, believing that the latter has replaced the venerable organization created by Henry Dunant and Gustave Moynier. Showing that the ICRC still existed, and most importantly continued to act, was therefore a matter of survival.

Looking back to understand the present

Watching these four documentaries, one can only be surprised by the topicality of their content. The fight against typhus obviously reminds us of the current COVID-19 sanitary crisis, while images of Russian refugees confined in the Istanbul agglomeration in the 1920s echo the current migrant crisis. As for children, they remain not only a major concern of humanitarian organizations, but also, since WWI, the iconic figure of suffering, particularly suffering caused by armed violence. The limited presence of international war in these short films is equally surprising, as such conflicts were at the heart of the ICRC’s mandate at the time and the consequences of the past global war – like the necessity to repatriate prisoners – had motivated their production. This relative absence already seems to foreshadow the evolution of war itself, with a rarefaction of international armed conflicts and the multiplication of civil wars, internal troubles and other types of conflicts in the latter half of the century.

Better yet, we can see that the ICRC’s first films already had in their DNA the characteristics of what would later be called “humanitarian cinema”, i.e. cinema as a way of documenting man-made or natural disasters to get financial backing and gain a competitive advantage. With its first film productions in 1921, the ICRC was already doing all of this at once. Additionally, the organization was innovating. It showed that it too knew how to use the modern technology of cinema and was thus not a backward-looking organization, ready for the museum, as the League of Red Cross Societies seemed to believe. In that sense, the four 1921 films prove a widespread assumption wrong: humanitarian innovation indeed far predates the digital age.

Comments