Table of Contents

Introduction – General Overview – The International Prisoners of War Agency – ICRC Delegations and Visits to POW’s Camps – The Repatriation of Captives – The ICRC and the Aftermath of the War – Depictions of Wartime Captivity

Introduction

World War I represents a major turn in the history of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Though it had been founded over fifty years earlier, the humanitarian organization still had limited field work experience when the war broke out in the summer of 1914. The ICRC was then first and foremost a local philanthropic society, with less than a dozen members and restricted financial means. The outbreak of the war, its unparalleled expansion and growing number of casualties put the Committee in an unprecedented situation. The explosion of humanitarian needs on the ground triggered a rapid and substantial transformation of the organization, in line with its unwavering commitment to alleviate the sufferings of war victims.

While volunteers of the National Societies of the Red Cross worked to bring relief and aid to the wounded close to the battlefield, the Committee based in Geneva dedicated its humanitarian efforts to another major category of war victims: those who had fallen in enemy hands. It founded a tracing agency – the Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre (AIPG), hereafter the International Prisoners of War Agency – that collected all the information it could gather on the fate of prisoners of war and civilian internees and relayed it to their home countries and their relatives. [1] Delegates from the ICRC visited detention camps, negotiated to improve POWs’ conditions of detention and published their observations. The ICRC’s efforts to restore contact between captives and their families were an essential source of hope and well-being for both sides. Acting as the custodian of international humanitarian law, the ICRC pressed the states parties to the conflict to respect the conventions of international law they had ratified. The organisation spoke out to clarify the interpretation of certain of these conventions’ dispositions and recorded complaints about their violation. The most notable reported offenses included the bombing of sanitary installations or ambulances, the torpedoing of hospital ships and the abusive use of the protected Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems. Behind the scenes, the Committee negotiated with states to allow for the repatriation of sanitary personnel and wounded prisoners of war. It also tried to put an end to the vicious circle of retaliation between belligerents, which had terrible consequences for their captives.

For the aforementioned activities, the Committee could rely on the framework for its action provided by the Geneva Convention and the resolutions of the International Conferences of the Red Cross. But it also innovated to adapt to the reality of the conflict and best serve the victims of the war, extending for example the work scope of its tracing agency to document the whereabouts of civilian internees. It also fought against the use of poison gas, a new weapon that did not discriminate between soldiers and civilians. As the relations between the different National Societies of the Red Cross and Red Crescent became impaired by growing tensions, the ICRC strove to maintain the unity of the “International Red Cross”, acting as a mediator and collecting complaints from all sides.

For its work in favour of the victims of the war, the ICRC was awarded in 1917 the Nobel Peace Prize, received with minimal celebration. Finally, as the hostilities came to an end, the Committee organised the repatriation of former prisoners of war and brought relief to the populations of the defeated states. Collaborating closely with the newly founded League of Nations, it contributed to making humanitarian aid a central preoccupation on the international community’s agenda.

Conceived as an entry point into the ICRC’s Library and Archives rich collections, this research guide aims to provide an overview as comprehensive as possible of the main documentary resources available on the activities of the ICRC during the war. Each of the following sections is dedicated to a specific field of action of the organization, listing both primary sources and related works of secondary literature. Additional reading suggestions are provided, as well as a series of relevant online resources (including complementary research guides, online platforms, and digitized archival collections from academic, cultural or heritage organizations). All the publications presented here are available for consultation in the ICRC Library. Some have also been digitized and are available online in full text (see the links provided for more details).

The guide also includes a first – non-exhaustive – selection of fonds from the ICRC archives. Unpublished sources from these public archives can be consulted upon appointment at the institution’s headquarters in Geneva; see the service’s page on icrc.org for more information. The guide provides links to the photos and films available online on the ICRC audiovisual archives portal. The publication of this guide follows the digitization of a series of source materials related to the activity of the ICRC during WWI and for which direct links are included below. Questions and suggestions to improve the guide can be sent at library@icrc.org.

General Overview

Primary Sources

Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge (1914 – 1918)

Ancestor of the International Review of the Red Cross, the Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge became in 1869 the central means of communication of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. Its publication was not interrupted by the outbreak of the war; a new and augmented issue of the Bulletin was distributed every three months during the conflict. These issues included the circulars and statements produced by the Committee, as well as articles documenting its current activities and internal organization, its funding and finances, and its contacts with other relief societies and state officials. In a few lines for each country, the Bulletin reported on the work of the National Societies of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in favour of the victims of the conflict. The Committee would also write down the protests against violations of the Geneva Convention it received in the journal’s pages.

Signed by Paul Des Gouttes, the Committee’s secretary, this little book summarized the organization’s action from October 1914 to October 1916. It is divided into two parts, matching “the two branches of activities of the International Committee: the old branch and, so to speak, the traditional one, relative to wounded or sick soldiers; and the new branch, relative to prisoners of war, ” as the author explained.

Actes du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre 1914 – 1918 (1918)

In this volume published at the end of the war were reprinted all the circulars, letters and appeals issued by the ICRC from 1914 to 1918. It is thus a testimony to the organization’s persistent efforts to strengthen compliance with international humanitarian law and clarify the interpretation of certain legal dispositions, such as the treatment of military sanitary personnel (see for example the circular dated December 7 1914).

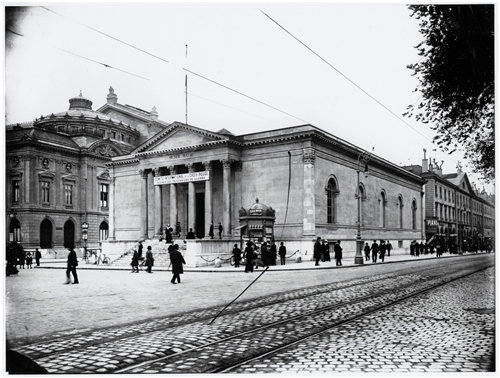

Geneva, 1921. Plenary session of the 10th International Conference of the Red Cross (Ville de Genève/ICRC/F. Boissonnas)

Rapport général du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge sur son activité de 1912 à 1920 (1921)

Submitted to the 10th International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, this report was meant to give the Movement’s National Societies a general account of the Committee’s last eight years of activity. Succinct but comprehensive, it presents its humanitarian activities and describes its relations with a series of humanitarian actors, both inside and outside the Movement. Since the report also covers the years immediately preceding and following the conflict, it illustrates how the experience of the war transformed the Committee and shaped its future action.

Related ICRC archival fonds

- A CICR, sous-fonds A CS (1912-1923), International Committee of the Red Cross, Secretariat of the Committee.

- A CICR, sous-fonds C G1 (1914-1922), First World War: International Prisoners of War Agency.

- A CICR, sous-fonds A PV (1914-1923), Plenary sessions of the Committee and its Commissions.

- A CICR, série B CR 00 (1916 – 1951) National Societies of the Red Cross and Red Crescent.

Secondary Literature

François Bugnion, Confronting the hell of the trenches : the International Committee of the Red Cross and the First World War (2018)

« In terms of the number of nations involved, the duration of the conflict and the resources deployed, the First World War constituted a fundamental break with the past. […] In the first few months of the conflict, the International Committee of the Red Cross set up a system of operations that remains the cornerstone of its action today: tracing missing persons, restoring contact between prisoners and their families, visiting prison camps, delivering aid and repatriating ex-detainees. »

In addition to providing a synthetic but thorough overview of the activities of the ICRC during the Great War, this publication describes how the extraordinary circumstances of this unprecedented conflict led to a profound transformation of the institution, one which would define its direction for the years to come.

From the same author, see also the reference work The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Protection of the War Victims, which, combining a historical and a legal approach, traces the evolution of the ICRC’s mandate and presents its role as promoter and custodian of international humanitarian law from 1864 to the turn of the 21st century.

Cédric Cotter, (S’)aider pour survivre : action humanitaire et neutralité suisse pendant la Première Guerre mondiale (2017)

Examining the ICRC’s action during the Great War, this PhD thesis brings to light the role the organization played in the construction of Switzerland’s humanitarian tradition. The author presents the challenges faced by the ICRC during the war and discusses how the Committee implemented its own principles of impartiality and neutrality. He analyses how these core principles of the ICRC’s approach were connected to Switzerland’s own neutrality in the conflict. His analysis of the ICRC’s work has the merit of replacing it within the broader panorama of humanitarian action in Switzerland and the cohabitation of multiple relief societies during the Great War.

From the same author, see also the article Les élites genevoises au service de la Croix-Rouge (2016) and two collaborations with historian Irène Herrmann, Quand secourir sert à se protéger : la Suisse et les œuvres humanitaires (2014) and Nobel de la paix en pleine guerre : la Croix-Rouge et la Suisse en 1914-1918 (2017). With a similar approach, two recent publications focusing on the role of Switzerland during the First World War also include an account of the ICRC’s action : La Suisse et la guerre de 1914-1918 / Christophe Vuilleumier (2015) et 14/18 : la Suisse et la Grande Guerre / Roman Rossfeld (2014).

André Durand, History of the ICRC : From Sarajevo to Hiroshima (1984)

Second volume in a series of five dedicated to the history of the ICRC, this book covers the period from the Tripolitan War (1911-1912) to the end of the Second World War. The chapter focusing on the Great War addresses the following topics : the foundation and management of the International Prisoners of War Agency, encouraging belligerents’ compliance with the Geneva and Hague Conventions – particularly of dispositions regarding the repatriation of medical personnel and wounded soldiers – , and relief actions for the benefit of prisoners of war and civilians. It thus offers a good overview of the ICRC’s activities during the war, recontextualized in line with the organization’s development through the years.

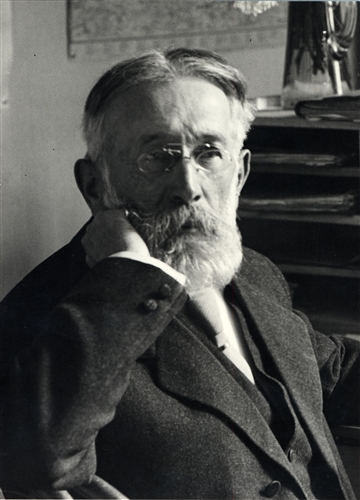

Gustave Ador (1845 – 1928), ICRC President, Founder of the International Prisoners of War Agency and Federal Councillor

Gustave Ador (1845-1928) joined the Committee in 1870 and officially took over the presidency in 1910, but had relieved his predecessor Gustave Moynier of many of his presidential duties in 1903 already. He worked to develop the Committee’s activities to help prisoners of war, at a time when the organization’s official mandate – as stipulated in the 1864 Geneva Convention – was still limited to the protection and assistance of sick and wounded soldiers and sanitary personnel. In 1912, during the 9th International Conference of the Red Cross, he secured the adoption of a resolution giving the Committee the responsibility of two major missions in favour of prisoners of war for future conflicts : managing a tracing agency to document the fate of prisoners and inform their relatives, and sending relief packages to the camps.

Acting on this resolution, Gustave Ador called for the foundation of the International Prisoners of War Agency in 1914 and assumed its directorship. During the conflict, he also conducted humanitarian diplomatic efforts on behalf of the ICRC. He notably personally negotiated with belligerents the repatriation or exchange of prisoners of war. In 1917, he was called to join the Swiss Federal Council and became the head of the country’s Department of Foreign Affairs. For more information, see these selected publications which retrace Ador’s life and career : Un homme d’Etat suisse : Gustave Ador, 1845-1928 / Frédéric Barbey, Gustave Ador’s stepson (1945) ; Gustave Ador : 58 ans d’engagement politique et humanitaire / Roger Durand et al. (1996) / Gustave Ador : fondateur et patron de l’Agence des prisonniers de guerre 1914-1918 / Roger Durand (2015).

Véronique Harouel, Genève – Paris : 1863-1918 : le droit humanitaire en construction, 2003.

This thesis retraces the genesis of international humanitarian law through the study of the relations between the ICRC and France. It first relates the history of the adoption of the first Geneva and Hague Conventions, before analysing their application during the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and the First World War. Titled ‘l’épreuve du jamais-vu : la tourmente de la Grande Guerre’ (‘The unprecedented test : the Great War’s turmoil’), the chapter focusing on WW1 not only looks at the ICRC’s action in favour of the military fallen in enemy hands, but also at its efforts to implement a right to intervene to rescue civilians. The author thus brings to light the first steps taken by the institution in the long process leading to the adoption of the Geneva Convention relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war (1949) thirty years – and another world conflict with most horrifying humanitarian consequences – later.

Lindsey Cameron, The ICRC in the First World War : Unwavering belief in the power of law, 2015

In this article, Lindsey Cameron reviews the ICRC’s efforts during the First World War to ensure the belligerents’ compliance with the 1906 Convention on the Wounded and Sick and the 1907 Hague Convention. The author examines the ICRC’s point of view on the implementation of these two conventions and looks at the way it handled allegations of violations of international humanitarian law. Finally, she shows how the ICRC engaged in a legal dialogue with States on the interpretation of various dispositions of IHL treaties, thus affirming its position as expert, guardian and promoter of this body of law.

Further readings from the ICRC Library Back to the table of contents

The International Prisoners of War Agency

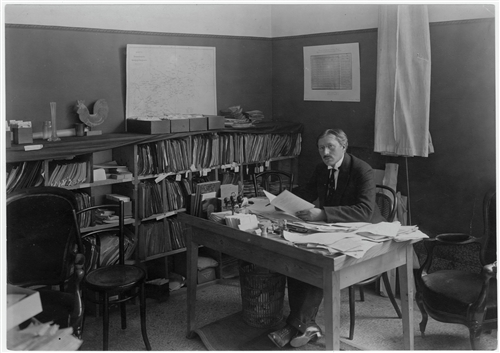

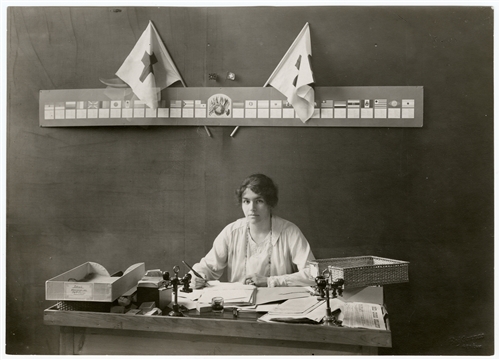

In accordance with the aforementioned resolution passed at the International Conference held in Washington in 1912, the ICRC announced on August 27 1914 that it was opening an international relief and intelligence agency for prisoners of war. In the course of the conflict, its collaborators collected, centralized and processed all the information they could obtain on the fate of prisoners of war and civilian internees, including the lists of captured men handed over by the belligerents. They would then pass on this information to the authorities of the captives’ country of origin. They also handled the countless requests coming from relatives of captured and missing individuals, desperate to have news from their family members. It was a titanic task; the Committee soon realized that the human and financial resources originally planned would not suffice. Austrian author Stefan Zweig described the efforts of these early days of the Agency, as “trying to empty with a thimble the sea of horrors to come”. [2]

Adapting to the needs and quickly expanding its activities, the Agency moved to the Rath Museum in Geneva and undertook to systemize and rationalize the way it processed and exploited information. It recruited many people to help with this task, only volunteers at first, then actual employees. Their number reached 1’200 at the end of the year 1914, before stabilizing around a few hundred, as the Agency was able to share the workload with other national prisoners of war agency and research offices.

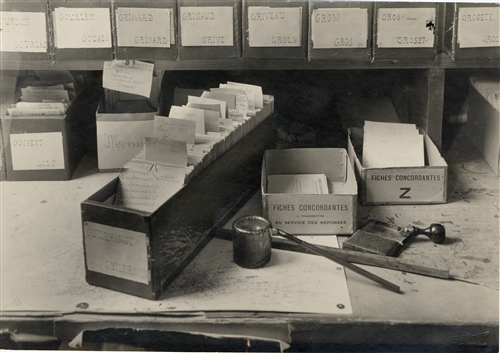

During the conflict, the Agency’s collaborators processed up to 30’000 nominal information received in letters and lists every day. One of its services also allowed families to send letters, money and parcels to prisoners of war. Today, we can follow the itineraries of over two million prisoners of war through the five million cards established by the Agency between 1914 and 1918 and their original sources, all accessible online via the ICRC’s Grande Guerre portal.

Primary sources

Nouvelles de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre (1916-1918)

As seen above, the Agency would pass information concerning a particular captive or internee directly to his home country and relatives. Additionally, it inaugurated in early 1916 the publication of a weekly journal, the Nouvelles de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre – the Agency’s News – to distribute the general information on POWs he received to the population. Those Nouvelles were organized by country and supplemented with various articles and communications prepared by the Committee, such as the list of injuries that would warrant repatriation (no 2, January 29 1916).

The minutes of the International Prisoners of War Agency’s meetings written between August 21 1914 and September 30 1919 have been edited and annotated by ICRC historian Daniel Palmieri and published online in 2015. For each date, a couple lines recap the content of the meetings held by the Agency. The reader can follow through the years the evolution of its workforce and activities, as they intensify and become more systematic.

The Agency communicated publicly on its activities during the conflict. One of its collaborators, Frédéric Barbey, recounted the early days of the organization in a 1915 article. That same year, the ICRC published the Organisation et fonctionnement de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève : 1914 et 1915. This short book described each of the Agency’s services, from its directorate to the postal service, and the preparation and filing of the prisoners’ cards. It also included portraits of the ICRC’s founders and a picture of its 1’200 volunteers. The following year, this information was updated in a new publication focusing in particular on the French investigation service of the Agency : Renseignements complémentaires sur l’activité de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève en 1915 et 1916. Etienne Clouzot, head of the Agency’s service concerning the Allied forces, also described its activities in the booklet Disparus et prisonniers : l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève.

The well-known novelist and playwright Stefan Zweig, after visiting the Agency, described it as the ‘heart of Europe’ in his short book Le cœur de l’Europe : une visite à la Croix-Rouge internationale de Genève. Copies of the book were sold for 50 cents during the war for the Agency’s benefit. A selection of copies has been kept in the ICRC Library’s heritage collection. To finance its humanitarian work, the Agency proved to be quite resourceful. It sold photographs of POW’s camps, recuperated the stamps it received from around the globe and sold them to philatelists, and organized drama performances – casting its own collaborators onstage.

Finally, in 1919, as the International Prisoners of War Agency was about to leave the Rath Museum, the ICRC paid tribute to those who had helped the organization for the past four years. It published a book of photographs presenting the Agency’s various services and giving the reader an overview of the countless lists of prisoners, cards, letters and parcels that passed through the hands of its collaborators. The volume ends with the list of the close to 3,000 persons who took part in this effort; the attentive reader will notably recognize the name of famous French writer Romain Rolland.

The Documentation of the Agency’s Collaborators in the ICRC Library

From the early days of activity of the humanitarian organization to the present day, the ICRC Library has been collecting the literature used by the Committee’s members to document their work and keep abreast of the legal, medical or scientific advances of the time. The Library’s heritage collection reflects the development of the Committee and provides crucial information on its core preoccupations, its constant concern for the plight of conflict victims and determination to find humanitarian uses for the latest technological findings. The Library’s historical ‘Prisoners of War’ collection includes more than 300 documents on captivity during the First World War. Many of them belonged to the Agency between 1914 and 1918, as evidenced by the stamp on their cover.

These documents include testimonies from former captives, reports from relief societies assisting prisoners, military regulations on the treatment of captives and prisoners’ journals, as well as some maps of POWs’ camps or of front lines. Some of these documents seem to have been used by the Agency’s collaborators to inform their work during the conflict. A copy of the 1918 diplomatic agreement between the United States and Germany on the treatment of POWs belonged to ICRC vice-president Alfred Gautier (1858-1920). A collection of the provisions of international humanitarian law in force relating to the treatment of prisoners of war bears the signature of another key collaborator of the ICRC’s history, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, and many annotations from her hand.

The International Prisoners of War Agency’s Archives

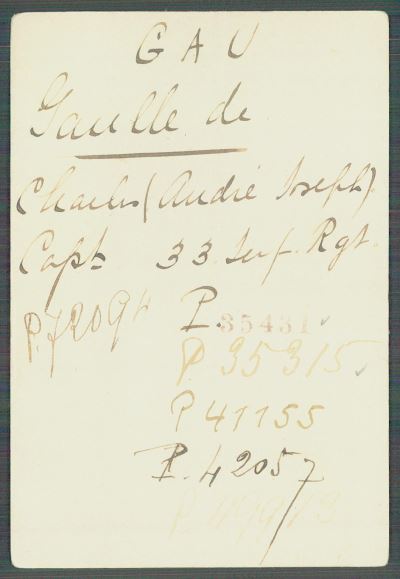

Card of the Army officer and future French president Charles de Gaulle (ICRC Tracing Archives, www.grandeguerre.icrc.org)

The five million prisoner cards created and filed by the staff of the International Prisoners of War Agency are now part of the ICRC’s Tracing Archives, which comprise all the individual data collected by the ICRC in past conflicts since 1870 up to today. Digitized in 2014, the cards can be explored on the ICRC’s Grande Guerre portal. For more information on this unique archival fonds, see the introduction available on the website, the contribution of Philippe Mathey – a former curator of the International Museum of the Red Cross, where part of the files are now displayed – in the volume Les prisonniers de guerre dans l’histoire : contacts entre peuples et cultures (2003), as well as the chapter ‘L’action du CICR pendant la Première Guerre mondiale : les archives de l’Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre’ in the volume La Suisse et la guerre de 1914-1918 (2015).

The ICRC’s Grande Guerre portal also gives access to a series of prisoner testimonies, postcards published by the ICRC illustrating its own activities as well as the daily life of the camps and hospitals and the list of WWI POWs’ camps.

Related ICRC archival fonds

- A CICR, sous-fonds C G1 (1914-1922), First World War : International Prisoners of War Agency.

- A CICR, A VS PROT LO AIPG (1914-1918), Guestbook of the International Prisoners of War Agency : signatures of collaborators and visitors.

- A CICR, P FF (1866 – 1923), Brochures and articles collected by F. Ferrière.

Audiovisual documents from the ICRC archives related to the Agency

Secondary Literature

Gradimir Djurovic wrote a thesis on the history of the ICRC’s Agency, published in 1981, which comprises a chapter on its action during the First World War. He explains the mechanisms of each of its services and presents the successive forms it took to respond to the 20th century’s conflicts. For a short on time reader, a brochure on the Agency published in English and French by the ICRC in 2007 is available online.

The Agency’s action for civilians has been studied by Jessica Pillonel in her Master’s Thesis in 2012 and by Matthew Stibbe in the article The internment of civilians by belligerent states during the First World War and the response of the International Committee of the Red Cross (2006). For a more general reflection on the protection of civilians, see also Annette Becker’s article The dilemmas of protecting civilians in occupied territory: the precursory example of World War I, featured in 2012 in the International Review of the Red Cross.

The presence of the great pacifist writer Romain Rolland among the Agency’s volunteers has interested several historians ; see Claire Basquin’s thesis, Romain Rolland et l’Agence des prisonniers de Genève (1914-1916) (1999), Martine Ruchat’s article ‘On a beaucoup à dire et peu à raconter’ : correspondance entre Romain Rolland et Frédéric Ferrière : 1914-1924 (2006) and Cynthia Schneider’s study, Romain Rolland et l’Agence internationale de prisonniers de guerre (2006). Ismaël Raboud (ICRC Library) and Marie Allemann (ICRC Agency Archives) co-authored a portrait of the most illustrious of the Agency’s volunteers on the blog CROSS-files.

Amidst the rich secondary literature studying captivity during the First World War, the following references can be found in the ICRC Library : Oubliés de la Grande Guerre : humanitaire et culture de guerre 1914-1918 : populations occupées, déportés civils, prisonniers de guerre / Annette Becker (1998), Les prisonniers en 1914-1918 : acteurs méconnus de la grande guerre / Frédéric Médard (2010), Soldats sans armes : la captivité de guerre : une approche culturelle / François Cochet (1998), La captivité de guerre au XXe siècle : des archives, des histoires, des mémoires / Anne-Marie Pathé (2012) et Fabien Théofilakis, Prisonniers de la Grande Guerre : victimes ou instruments au service des Etats belligérants / Olivier Lahaie et al., in Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains : revue d’histoire, No 253, janvier-mars 2014, p. 3-88.

In English, see The prisoners : 1914-1918 by Robert Jackson (1989), Violence against prisoners of war in the First World War : Britain, France and Germany, 1914-1920 by Heather Jones (2011), and the collective volume edited by Matthew Stibbe Captivity, forced labour and forced migration in Europe during the First World War (2013).

Dr. Frédéric Ferrière and the International Prisoners of War Agency’s Service for Civilians

Geneva doctor and ICRC member Frédéric Ferrière (1848-1924) is the man behind the creation of the civilian section of the International Prisoners of War Agency. The ICRC could draw on the resolution of the 1912 9th International Conference to support its action in favour of prisoners in 1914. But no similar disposition existed at that time for civilians who had fallen in enemy hands. Their internment, in conditions often more alarming than those of prisoners of war, was nevertheless a common practice of the belligerents. Requests for information reaching the Agency thus did not only concern missing soldiers, but interned civilians as well. The organization however decided at first not to extend its research activities to cover those cases. Dr. Ferrière opposed this decision and took the initiative to answer those requests himself. He was soon overwhelmed by the sheer volume of inquiries and succeeded in getting the Agency to reconsider its decision, having proved that the absence of a legal basis for this aspect of the work was not an insurmountable obstacle. The Agency opened a service for civilians and put Dr. Ferrière in charge. For more information, consult the biography authored by Adolphe Ferrière, Le docteur Frédéric Ferrière : son action à la Croix-Rouge internationale en faveur des civils victimes de la guerre (1948).

Further readings from the ICRC Library Back to the table of contents

ICRC Delegations and Visits to POWs’ Camps

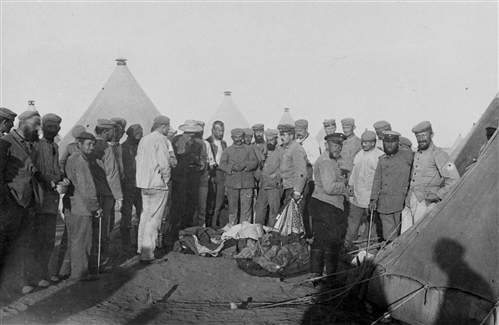

During the war, the ICRC consistently defended prisoners of war’s right to decent conditions of detention and negotiated with the belligerents to be allowed to visit the camps. In 1915, its delegates made a first series of visits to camps in Germany, Great Britain and France. Ultimately, it obtained permission from all the main belligerents to conduct visits of a similar nature on their territories.

In total, ICRC delegates visited 534 prisoners of war camps, mainly in Europe, but also in North Africa (Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt) and Asia (Siberia, Burma, Japan, British Indies). The ICRC delegates’ reports of visits were sent to the governments concerned. They were published and commercialized, as part of the series “Documents published on the occasion of the war of 1914-1918”.

Following the digitization of the ICRC delegates’ reports of visits to WWI POW’s camps, the Library has published a research guide on CROSS-files to facilitate their online consultation.

World War 1914-1918 : Reports on the visits of the prisoners of war camps

As the war raged on, the publication of these reports served first of all to inform civil society on the fate of those who had fallen in enemy hands. But they also allowed the Committee to counteract belligerents’ attempts to use the reports for propaganda, for example by publishing edited versions. The ICRC delegates’ accounts provided a neutral and detailed source of information on prisoner camps, a welcome alternative to rumours circulating in the press. They often painted a reassuring picture of the conditions of detention of POWs, which the analyses of historians nowadays tend to nuance.

Nonetheless, the publication of these often favourable reports had the effect of combatting belligerent reprisals. A country’s ill-treatment of prisoners became much more difficult to justify when reports of visits in the other side’s POWs camps described good conditions of detention. The ICRC delegates’ visits thus did have a positive effect on the conditions of detention, according to historians’ accounts. [3] For detainees, they also represented a rare and precious occasion for contacts with the outside world and the opportunity to air grievances. The publication of these reports in the middle of the conflict lead to a series of protests from belligerent states. The ICRC pointed out that it was targeted by accusations of complacency and partiality from both sides, which it pragmatically interpreted as a proof of its neutrality.

The historical ‘Prisoners of War’ collection of the ICRC Library, which comprises more than 300 documents on captivity during the First World War, includes a great find : two examples of forms used by the delegates to prepare and document their visits, with lists of questions to ask and elements to include in their reports. For example, a form prepared for the visit of camps of French prisoners of war in Germany listed questions on the camp’s infrastructures, the prisoners’ diet, their medical care, the disciplinary sanctions, their work and their correspondence, among others.

For more information on these visits, see the literature on prisoners of war introduced above, as well as Richard Ronan’s article, Succès et limites des puissances protectrices : le cas des prisonniers civils et militaires dans l’ouest de la France pendant la Première Guerre mondiale (2010). The visits of doctor and ICRC delegate Fritz Paravicini (1874-1944) to the POWs’ camps in Japan were the subject of a study in Japanese by Shiro Ohkawa. An English summary of the publication is available in the ICRC Library.

Audiovisual documents from the ICRC archives related to Prisoners of War

Further readings from the ICRC Library Back to the table of contents

The Repatriation of Captives

“All nations have an equal interest to see their own come back in sound health in both body and mind. Our conscience rises strongly against the extension of a detention that could deprive Europe of millions of human beings. (…) The war has been the cause of too many ruins and mournings, and too much blood has been shed for us not to listen to the voice of the heart and mercy and return to their homeland all those who can still be saved.” [4]

The International Committee of the Red Cross to the belligerents, Appeal for the repatriation of prisoners of war. Geneva, April 26 1917.

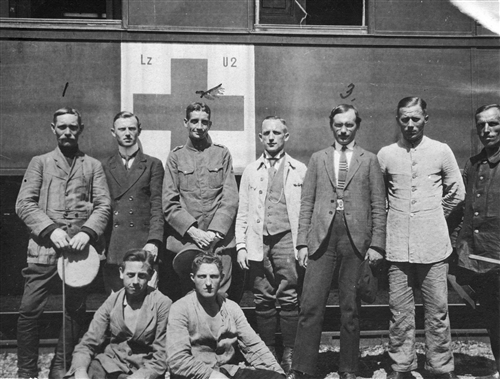

Already at the end of 1914, the ICRC opened negotiations with belligerents to convince them to repatriate part of their prisoners of war and civilian internees. Its priority was first to get the severely wounded sent back home. In March 1915, the Committee successfully negotiated the repatriation of convoys of injured French and German prisoners via Switzerland. These prisoners’ journey is narrated by the Swiss novelist Noëlle Roger in Le train des grands blessés (1916). In the Library, a series of lists of the French soldiers who were repatriated in 1915 can also be consulted.

The 1906 Geneva Convention stipulated that military medical personnel had to be repatriated without delay as soon as their presence was no longer absolutely required to care for wounded captives. During WWI, the belligerents accused each other of extending the captivity of such personnel without reason. Behind the scenes, the ICRC worked to ensure their repatriation. Its proceedings for the period include a communication to the belligerents dated December 7 1914 in which he reminded them of their obligations in that domain, as following their ratification of the Convention (‘Renvoi du personnel sanitaire : interprétation des articles 9 et 12 de la Convention de Genève du 6 juillet 1906’).

In spring 1916, as the war kept raging on, the ICRC expanded its efforts to encourage and facilitate the repatriation of prisoners of war in good health. On April 16, it issued an appeal calling for the release of those who had been imprisoned for a long time, or whose mental state might be a source of concern. It then facilitated the conclusion of agreements between belligerents allowing exchanges or repatriation of prisoners, like the one reached between the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire in January 1917, or the one between France and Germany signed in April 1918. A copy of the latter, perhaps received by the Committee at the time of its conclusion, is included in the historical ‘Prisoner of War’ collection of the ICRC Library.

When the hostilities finally came to an end, the ICRC worked to allow the repatriation of all the remaining prisoners of war. It is in particular the fate of the captives whose return had not been planned in international agreements which worried him, like the citizens of central Europe trapped in Siberia.

Several articles published in the International Review of the Red Cross – which replaced the Bulletin in 1919 – recount these efforts : Rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre centraux en Russie et en Sibérie et des prisonniers de guerre russes en Allemagne / Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer (May 1920) ; Rapport lu à l’Assemblée de la Société des Nations le 18 novembre 1920, sur l’œuvre du rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre / Fridtjof Nansen (December 1920) ; L’achèvement du rapatriement général des prisonniers de guerre par le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge / Lucien Cramer (May 1922). Finally, in September 1944, as the ICRC started to encourage the repatriation of the prisoners of the ongoing World War, Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer remembered the ICRC’s action after WWI : Le rapatriement des prisonniers du front oriental, après la guerre de 1914 – 1918 (1919 – 1922) (September 1944).

The ICRC’s efforts to encourage and execute the repatriation of prisoners of war have been studied by the historian Hazuki Tate. His thesis Rapatrier les prisonniers de guerre : la politique des alliés et l’action humanitaire du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (1918-1929) (2015), and the article he published the previous year in the journal Relations internationales Hospitaliser, interner et rapatrier : la Suisse et les prisonniers de guerre, are available in the ICRC Library. Two Master’s Theses focus on the same subject matter : Bolchévisme, droit humanitaire, dollar et Paix des vainqueurs : l’organisation du rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre centraux détenus en Sibérie après la Première Guerre mondiale, par la Mission Montandon du CICR (1919-1921), les Croix-Rouges nationales et la Société des Nations / Blaise Hofmann (2001) and Repatriierung 1920-1922 : zur Rückführung der Kriegsgefangenen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg / Sebastian Balzter (2005).

Related ICRC archival fonds

- A CICR, sous-fonds C G1 (1914-1922), First World War : International Prisoners of War Agency.

- A CICR, sous-fonds A CS (1912-1923), International Committee of the Red Cross, Secretariat of the Committee.

- A CICR, A PV, sous-fonds A PV (1914-1923), Plenary sessions of the Committee and its Commissions.

- A CICR, série B CR 001 (1918-1919), International Committee of the Red Cross, General Secretariat : ICRC missions after the 1914-1918 War.

Audiovisual documents from the ICRC archives related to the repatriation of captives

Further readings from the ICRC Library Back to the table of contents

The ICRC and the Aftermath of World War I

The humanitarian consequences of a conflict do not disappear at the immediate end of the hostilities. For the ICRC, the after-war years were characterized by its involvement in a series of international relief campaigns on an unprecedented scale. To respond to the humanitarian crises triggered by the conflict, the International Committee worked hand in hand with the newly created League of Nations, with National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and a range of other independent humanitarian actors.

They inaugurated new forms of international collaboration to handle the humanitarian fallout of the period’s political and social upheavals. The small book titled ‘Le Comité international de la Croix-Rouge : ses missions, 1918-1923‘ (1923) tells how the Committee helped to repatriate former POWs, fought against epidemics, cared for refugees from Russia and the Near East, supported the foundation of the International Union for Child Welfare and brought food relief to the starving Russian population, all in the five years following the end of the conflict. These same activities are presented in more detail in the General report of the ICRC on its activity from 1921 to 1923 (1923).

For more information related to the Committee’s work at the end of the war and its collaboration with the League of Nations, see the ICRC Library’s portrait of Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930), LoN delegate and first High Commissioner for Refugees. His humanitarian action in the 1920s was characterized by a very close collaboration with ICRC delegates. Kimberly A. Lowe’s thesis, The Red Cross and the New World Order : 1918-1924 (2014), identifies the stakes of this crucial period for the development of the humanitarian organization.

Further readings from the ICRC Library Back to the table of contents

The Road to the 1929 Geneva Convention : The ICRC and The Protection of Prisoners of War after World War I

The experience of the war brought to light the shortcomings of international law when it came to protecting prisoners of war. To fill gaps in the provisions of the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions, the belligerents concluded several special agreements in 1917 and 1918.

At the end of the conflict, it appeared therefore indispensable to draw the necessary lessons from the challenges of the last four years and to adapt international law to the reality of international conflicts. In 1921, the participants of the International Conference of the Red Cross agreed on the need to adopt a special convention concerning the treatment of prisoners of war, a “prisoner of war code”.

The draft Convention prepared by the ICRC in reply was submitted to the Geneva Diplomatic Conference of 1929. Though it did not replace the provisions of the Hague Conventions, the Convention relating to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of July 27 1929, supplemented them. It introduced new, important legal dispositions, such as the prohibition of reprisals and of the collective punishment of prisoners of war. For an analysis of the repercussions of the First World War on the development of the legal protection of POWs, see the article by Neville Wylie and Lindsey Cameron, The impact of World War I on the law governing the treatment of prisoners of war and the making of a humanitarian subject.

Further readings from the ICRC Library Back to the table of contents

Related ICRC archival fonds

- A CICR, sous-fonds C G1 (1914-1922), First World War : International Prisoners of War Agency.

- A CICR, sous-fonds A CS (1912-1923), International Committee of the Red Cross, Secretariat of the Committee.

- A CICR, série B Mis San (1919-1920), International Committee of the Red Cross : sanitary missions in Central and Eastern Europe and Russia.

- A CICR, série B CR 001 (1918-1919), International Committee of the Red Cross, General Secretariat : ICRC missions after the 1914-1918 War.

Films from the ICRC Archives on the ICRC’s activities after the War

Depictions of WW1 Captivity : POWs’ Journals and Testimonies in the ICRC Library

‘BIM : British interned magazine’, ‘l’intermède’, ‘le canard’, ‘l’interné’ or ‘The wooden city’ : during the First World War, journals gave a voice to prisoners of war and documented their life in detention, their sufferings and distractions. As historical sources, POWs’ journals represent today invaluable firsthand accounts of wartime captivity. The interested reader will find here the list of journals received by the ICRC or the Agency during the conflict, which are now part of the Library’s historical ‘Prisoners of war’ collection.

Many former prisoners of war published stories of their capture and detention in the years following their release, sometimes heavily drawing on novelistic conventions. The ICRC Library comprises about fifty of these stories for the First World War, most of which were written by former French or German POWs. This collection is representative of an actual literary genre of the period. It reflects both the diversity of the prisoners of war’s individual trajectories and the similarities of their misfortunes and the ingenuous ways they devised to survive (or manage) captivity.

The ideological orientation and context of publication of these stories encourage us to be slightly critical of the historical accuracy of the information included. Even if they do not always have an indisputable historical or literary value, these stories clearly remain valuable sources; they reflect the experience of individual POWs as well as the mentality of an era on wartime captivity. During the hostilities, the International Prisoners of War Agency seems to have collected a couple of copies of these stories, perhaps as a source of information on the fate of prisoners of war. Its stamp can be found for example on the first page of Israel Cohen’s book The Ruhleben prison camp : a record of nineteen months’ internment (1917) as well as in Georges Desson’s Souvenirs d’un otage (1916). Find here all the stories of captivity during the First World War kept in the ICRC Library.

For Further Research : an Overview of Digitized Records and POWs’ Stories Available Online

- 1914-1918 online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War

- British Library World War One portal

- The National Archives (UK), Records of the First World War

- Imperial War Museum : Voices of the First World War : Prisoners of War

- Research guide on World War I from the Library of Congress

- Site Europeana 1914-1918 : official and undisclosed stories of the First World War

- Portail Première Guerre mondiale de la Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Portail 14-18.ch : Switzerland during the Great War, explored through the National Library’s collection of postcards

[1] The ICRC’s commitment to help relieve the mental sufferings of the war and keep families informed about the whereabouts of prisoners of war actually dates back to the Franco-Prussian War (1870), where it set up a first tracing agency for POWs – the Bureau de renseignements de l’Agence internationale de secours aux militaires blessés et malades à Bâle. For more information about this ancestor of the AIPG, see the dedicated chapter in Gradimir Dujurovic’s thesis The Central Tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The reports of this Agency – in German and French – are part of the ICRC Library’s heritage collection (AF 3010 / AF 3015 / AF 3016).

[2] Stefan Zweig, Le cœur de l’Europe : une visite à la Croix-Rouge internationale de Genève, Genève : Ed. du Carmel, 1918.

[3] See for example Cédric Cotter’s argumentation in S’aider pour survivre : action humanitaire et neutralité suisse pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, Chêne Bourg : Georg, 2017, 75.

[4] Our translation of an extract from Le Comité International de la Croix-Rouge aux Belligérants, Appel en faveur du rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre. Genève, le 26 avril 1917. The original text in French reads : « Toutes les nations ont un égal intérêt à voir revenir leurs enfants sains de corps et d’esprit. La conscience s’élève avec force contre la prolongation d’une détention qui priverait peut-être l’Europe de millions de créatures humaines. (…) La guerre a accumulé trop de ruines, trop de deuils, a fait couler trop de sang pour ne pas écouter la voix du cœur, de la pitié, en restituant à leurs patries tous ceux qu’on peut encore sauver ».

Comments