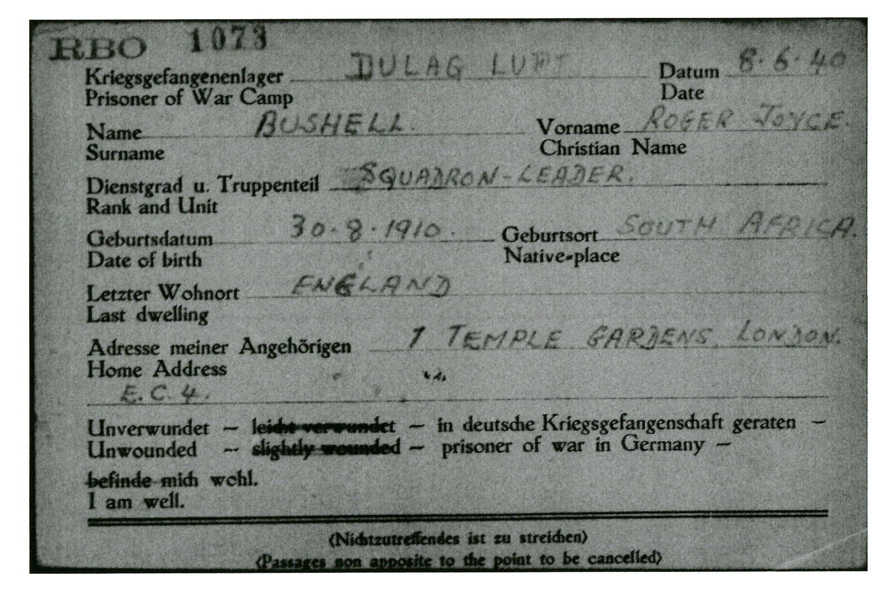

Photo of Roger Bushell, CC-BY-SA-4.0

Looking for a way out is surely on the mind of every prisoner-of-war. The reasons are varied: to regain freedom, to take back control of their lives, to choose their own fate, to strike back for the humiliations endured, or to return to the fight. For a mass escape, there is also the idea of waging a battle from within: diverting troops from the front by forcing the enemy to hunt down escapees across the country.

Thinking of prisoner-of-war escapes during World War II, images of the famous movie The Great Escape with Steve McQueen immediately come to mind. The film is based on the true story of Allied pilots who broke out of Stalag Luft III during the night of 24-25 March 1944.

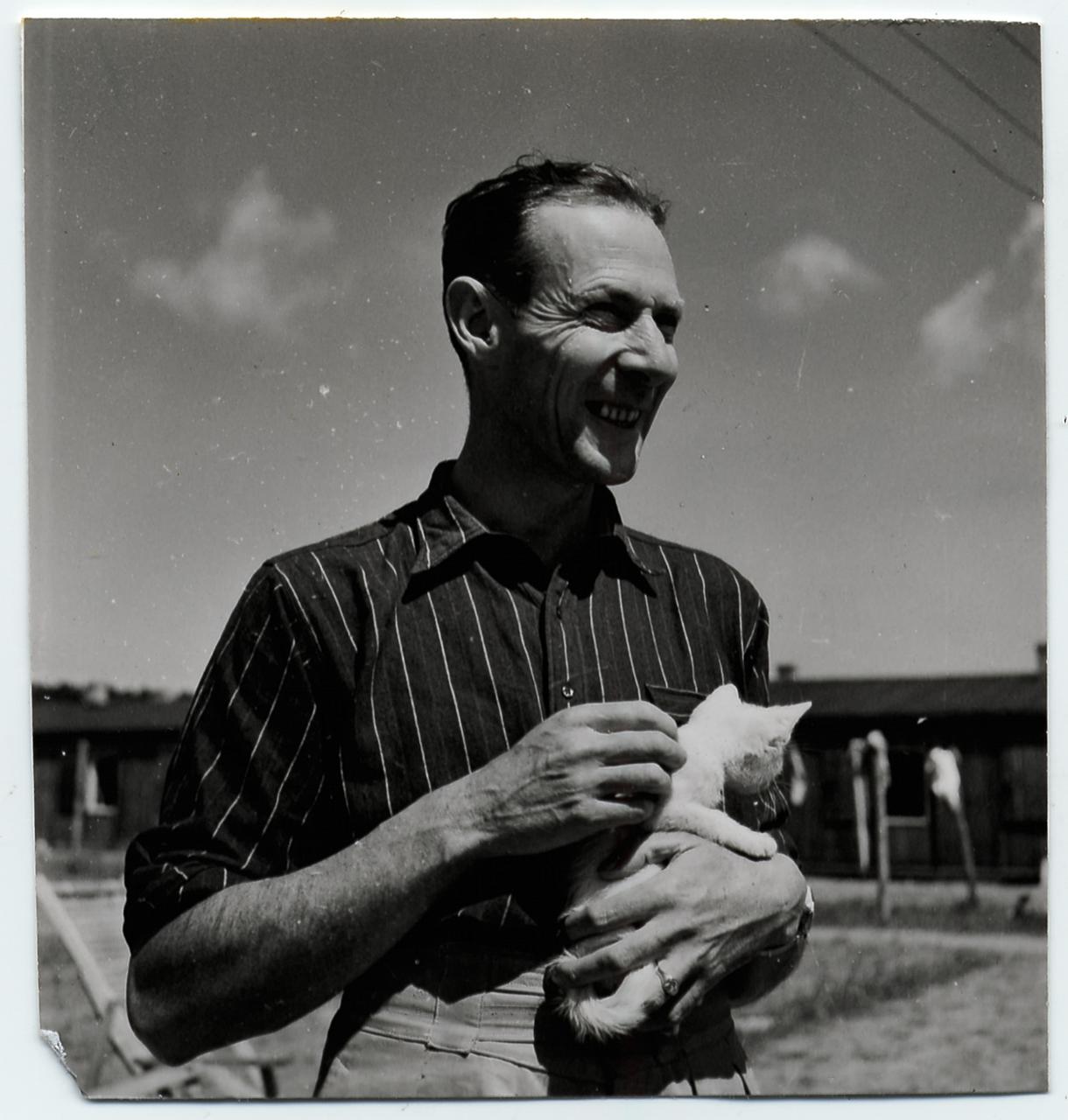

Among them was the “mastermind” of the escape, Roger Bushell, a South African pilot in the Royal Air Force. When it came to escaping captivity, Bushell could almost be called a professional. A former squadron commander shot down during the Battle of Dunkirk in May 1940, he believed that every captured officer had a moral duty to attempt to escape. His captivity first began at Dulag Luft, a transit camp for airmen.

Capture card of Roger Bushell, ACICR C G2 FR GB, alphabetical file

From the start, he formed a close friendship with the camp’s designated prisoners’ representative, Harry Day, and fellow pilot Jimmy Buckley.

Photo of Harry Day, V-P-HIST-01636-01, ICRC

The three men set up an “Escape Committee” to plan breakouts. In June 1941, 17 prisoners made their first attempt to escape through a tunnel. Bushell didn’t use the tunnel; instead, he slipped away at night, hiding in the camp’s sheep barn. Just a few kilometers from the Swiss border, he was recaptured by German troops before being transferred to Stalag Luft I along with Day, Buckley, and the other recaptured prisoners.

Detained at Stalag Luft I, Bushell sent the following message to the visiting ICRC delegate on 2 July 1941[1] :

« Messages also to Mrs. Paravacini (of Bern) from Pilot Squadron Leader Bushell, who almost paid Mrs. Paravacini a visit some time ago. He was held, entirely against his will, just a few meters from the border, with the Säntis in sight, and had to return to his camp, from where he was transferred to Barth Vogelsang, where he currently resides. He has, however, not given up on his travel plans. »

He was, of course, referring to his attempt to escape via Switzerland. Behind the deliberately playful and casual tone, the determination to plan a new attempt is loud and clear.

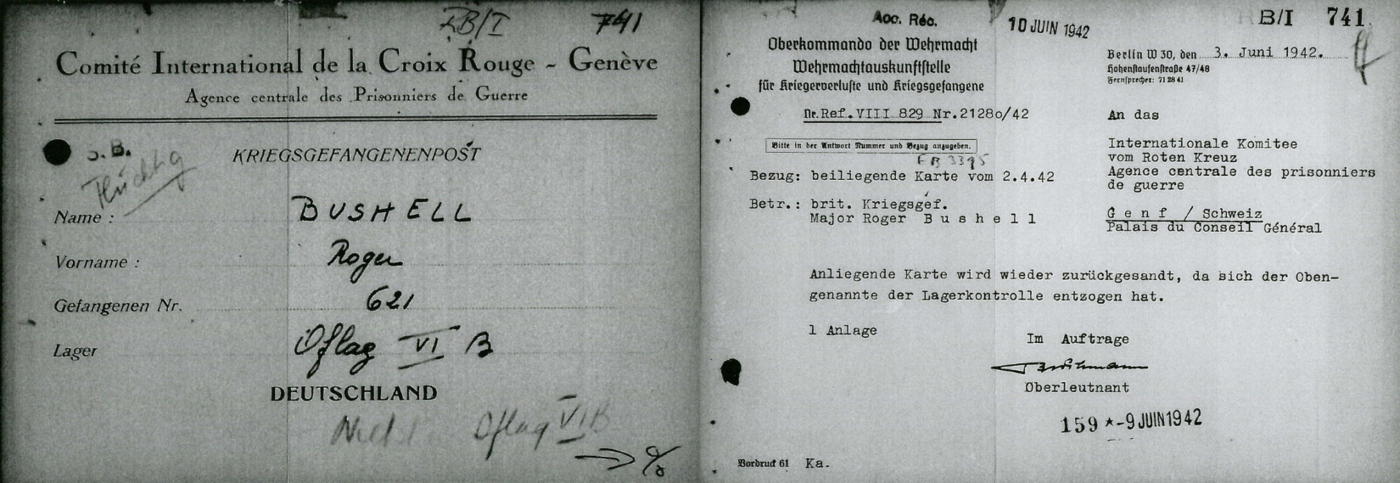

During another transfer from Oflag X C to Oflag VI B on 8 October 1941, Bushell managed to jump from the train and make his way to Prague with a Czechoslovak fellow prisoner.

Card notifying of Roger Bushell’s escape, ACICR C G2 GB, RB/I 741

They stayed in hiding in Prague for eight months, thanks to the help of the local resistance. Eventually betrayed, they were arrested by the Gestapo. The family that had sheltered them was executed. Bushell endured relentless interrogations, as the Gestapo suspected he might have been involved in the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the Nazi Deputy Governor of Bohemia-Moravia, in May–June 1942. This only deepened Bushell’s hatred of the Nazis. He knew that if he fell into the hands of the Gestapo again, he would be executed.

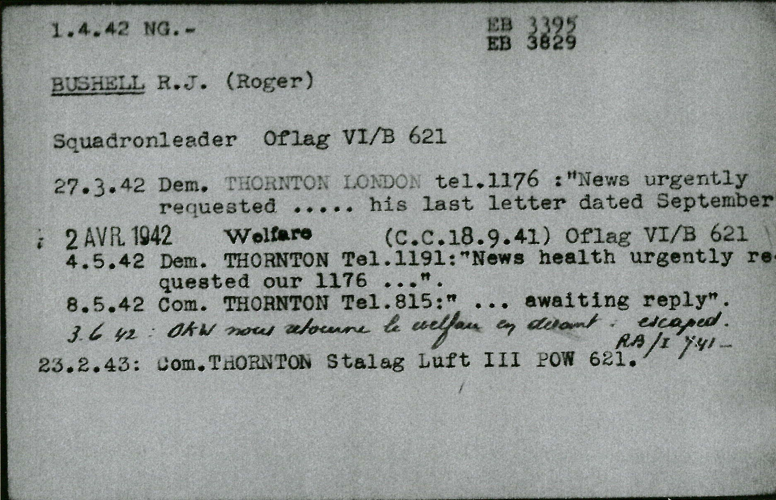

During this period of silence, the ICRC received multiple requests from his worried family, desperate for news of his fate.

Investigation form relative to Roger Bushell, ACICR C G2 GB, alphabetical file

Roger Bushell was eventually transferred to Stalag Luft III, a POW camp for Allied air force officers located near the town of Zagan in Lower Silesia.

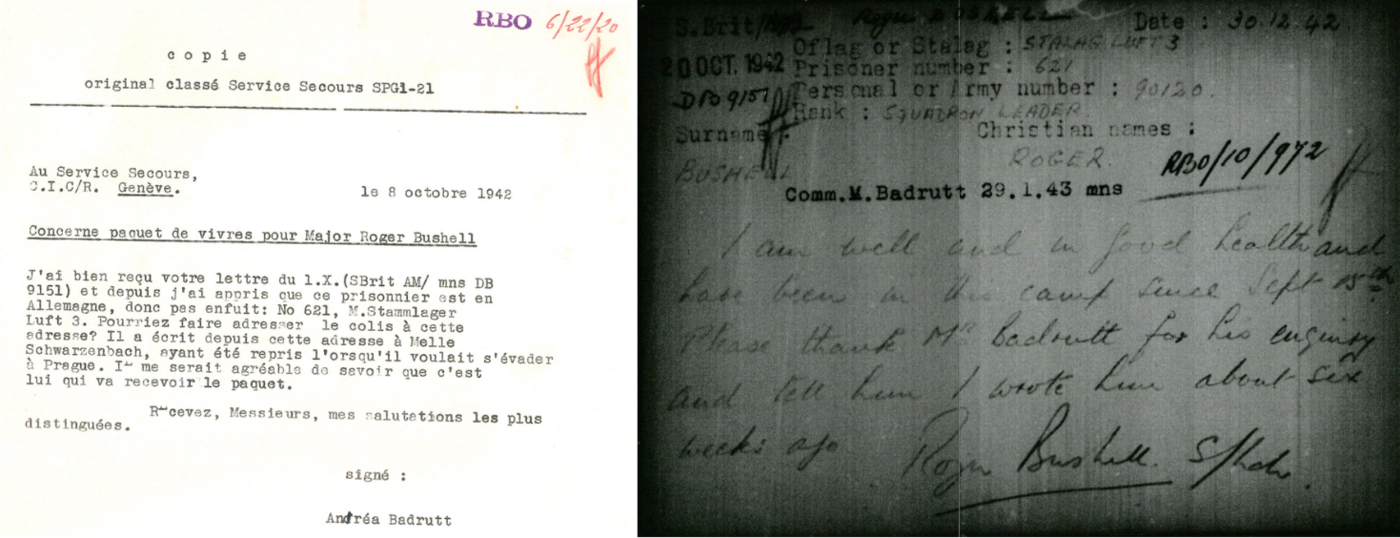

Left : Letter regarding a relief parcel for Roger Bushell, ACICR C G2 GB, RBO 6/22/20. Right : Card written in Roger Bushell’s own hand, ACICR C G2 GB, RBO/10/972.

Download here the July 1st 1942 list of new prisoners of war arrived at Stalag Luft III (ACICR C G2 GB, RBO 5/4/263).

Stalag Luft III was designed to prevent escapes. The Germans grouped there imprisoned airmen who had already attempted to break out. In their visit report of 13 September 1942, ICRC delegates noted: « The security measures are obviously very strict given the extremely numerous escape attempts. Rooms and prisoners are searched frequently, and the Kommandantur has a very diverse and extensive escape museum.» [2]

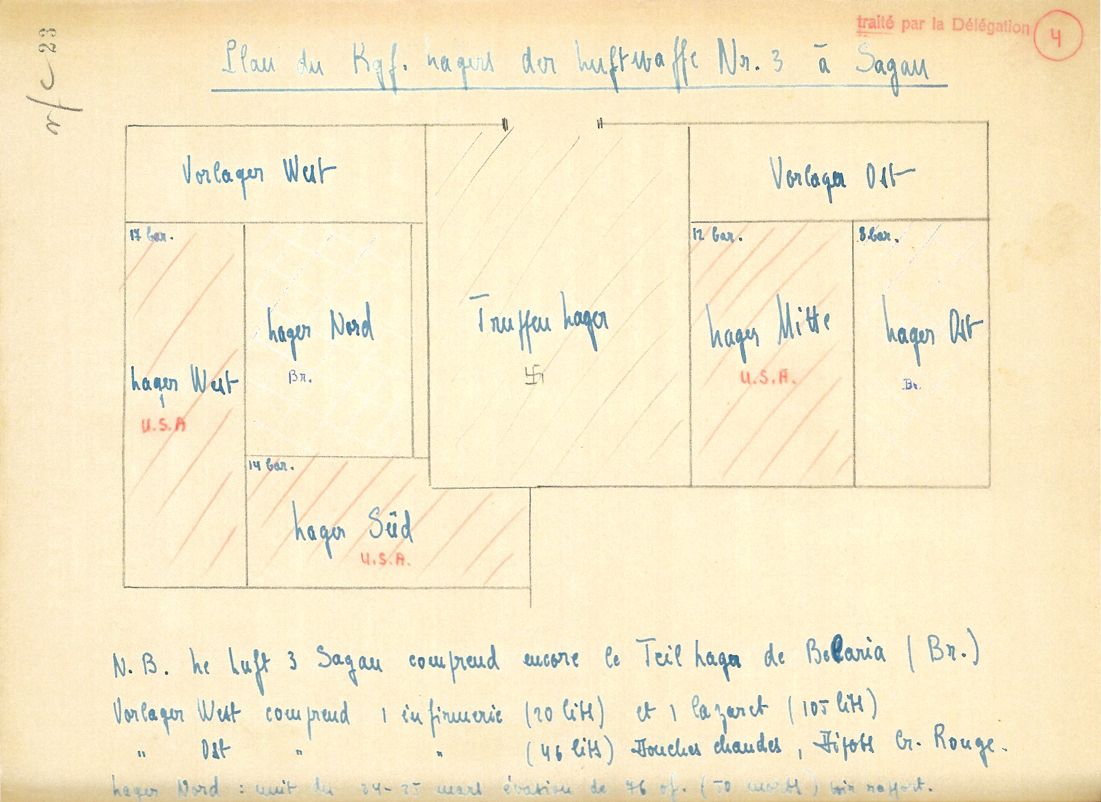

The camp was divided into several compounds, each separated from the others to limit contact between prisoners. British and Commonwealth prisoners lived in the northern compound.

Plan of Stalag Luft III, annex to the Visit Report of ICRC delegates to Stalag Luft III on 22 May 1944, ACICR C SC, RR 808

The German authorities had tightened security measures in the camp. Seismic microphones were installed to detect any tunnel digging, and the barracks were built on stilts.[3] This didn’t stop Bushell’s plans. His escape committee, known as “Committee X”, began planning a large-scale escape and started digging three tunnels, named Tom, Dick, and Harry, in the spring of 1943.

Each tunnel had to be dug more than 10 meters deep, over 100 meters long, and had to go under the German guards’ barracks. If over 600 prisoners took part in the effort, few knew the full plan and only a handful worked on digging the tunnels directly. Roger Bushell, who directed this massive escape project, earned the nickname “Big X”. To increase chances of success, he recruited the best specialists among the prisoners. Wallace Floody, for example, a Canadian pilot who had worked in mines, made good use of his prior expertise to design the tunnels.

For construction, the prisoners diverted materials supplied by the Germans. To shore up the tunnels, they needed a large amount of wood, which they took from furniture in the barracks. In total, roughly 4,000 bed panels, 1,370 bed slats, 635 mattresses, 35 chairs, 52 tables, and 90 bed frames were used.

A clue to all this missing material? The ICRC visit report of 26 July 1943 noted [4] :

« …it is very difficult to find certain accessory items needed to equip the camp. The Commandant assures us that he is doing everything possible to make the camp more comfortable by providing all necessities; yet he observes that a huge amount of material is being used in this camp, five times as much as in camps for German troops. »

During a visit by the representatives of the Swiss Protecting Power on 22 February 1944[5], prisoners requested wood to build air-raid trenches. The Germans refused, knowing the wood would actually be used for tunnels.

The prisoners also needed to light the tunnels. Early-day lanterns, with wicks made of the cloth from pyjamas and fueled with sheep fat, would not suffice. Electrical wires were stolen from German workers and an actual electrical network connected to the camp’s power supply was installed.

During the same 1944 visit [6], the Swiss representatives noted that prisoners requested new lightbulbs, but the Commandant refused, complaining that far too many were broken. Even the Swiss delegate admitted: “a great amount of bulbs and other material is doubtlessly broken when being used for digging tunnels”.

Ventilation was also required underground, for the escapees to have fresh air. Ventilation pipes were fashioned from empty powdered-milk cans, and a compressor was built from a fabric bag mounted on pieces of wood. One man operated the compressor like a rowing machine to pump air.

Another key challenge was removing the dirt from the tunnels. Prisoners sewed bags inside their pants to carry the dirt, then discreetly dispersed it during walks. They also built a wooden railway to move men and materials on carts pulled by ropes.

The prisoners had to plan their escape beyond the camp. Johnny Travis, a pilot from Rhodesia, prepared escape kits, including compasses made from Bakelite fragments taken from gramophones and magnetized parts of razor blades. Desmond Plunkett and his team created maps. Real identity papers were stolen or obtained from corrupt guards and copied by forgers. Uniforms were altered to pass as civilian clothes.

To mask the sounds of digging and other Committee X activities, the prisoners organized theatrical and musical performances. In their visit report of 13 September 1942, the ICRC delegates commented: « Intellectual activity is highly developed (theater, cinema, orchestra, various courses). This activity is encouraged by camp authorities ». [7]

All this preparation happened despite constant guard supervision. The Germans knew tunnels were being dug, but despite relentless searches, did not find them. Other unrelated escape attempts occurred from time to time. In July 1943, 30 to 40 officers made yet another attempt. « Discipline was tightened », says the original ICRC report [8] dated 26 July providing strictly confidential information on the increased surveillance that followed. [9]

Donwload here an excerpt from the visit report of ICRC delegates to Stalag Luft III on 26 July 1943 (ACICR, C SC, RR 643)

The first major setback for Committee X came in September 1943 : German guards discovered the tunnel called ‘Tom’ as it reached the woods. It was the 98th tunnel uncovered at the camp ! Work on the other two tunnels was halted for two months to avoid arousing suspicion.

In October 1943, three prisoners escaped from the eastern compound, getting out through a tunnel dug under a hollow wooden pommel horse used for gymnastics. This motivated Bushell to move to Plan B: work was resumed on the ‘Harry’ tunnel, while ‘Dick’ was abandoned and repurposed for storage. The entrance to the ‘Harry’ tunnel was hidden beneath a stove in barrack 104. The stove remained always lit to prevent guard scrutiny.

In March 1944, a group of twenty prisoners, including Wallace Floody, were caught removing tunnel dirt from their clothing. They were immediately transferred to another camp. Floody, who had engineered the tunnels, would not be able to take part in the escape.

Finally, everything was set for the night of March 24–25, 1944.

Out of the 600 prisoners who had helped prepare the escape, only 200 would actually take part. Priority went to those with the best language skills or a track record of previous escape attempts. The remaining spots were assigned by lottery to those who had worked hardest to make the plan possible.

The tunnel was 101 meters long, 10 meters deep, and just 60 cm wide. The first escapee exited at 10:30 pm. Ten men would follow every hour.

Unfortunately, the tunnel turned out to be about 10 meters too short and did not reach directly into the woods, away from the guards’ view. The prisoners had to wait for the watchtower guard to look the other way before emerging, which slowed down the entire operation.

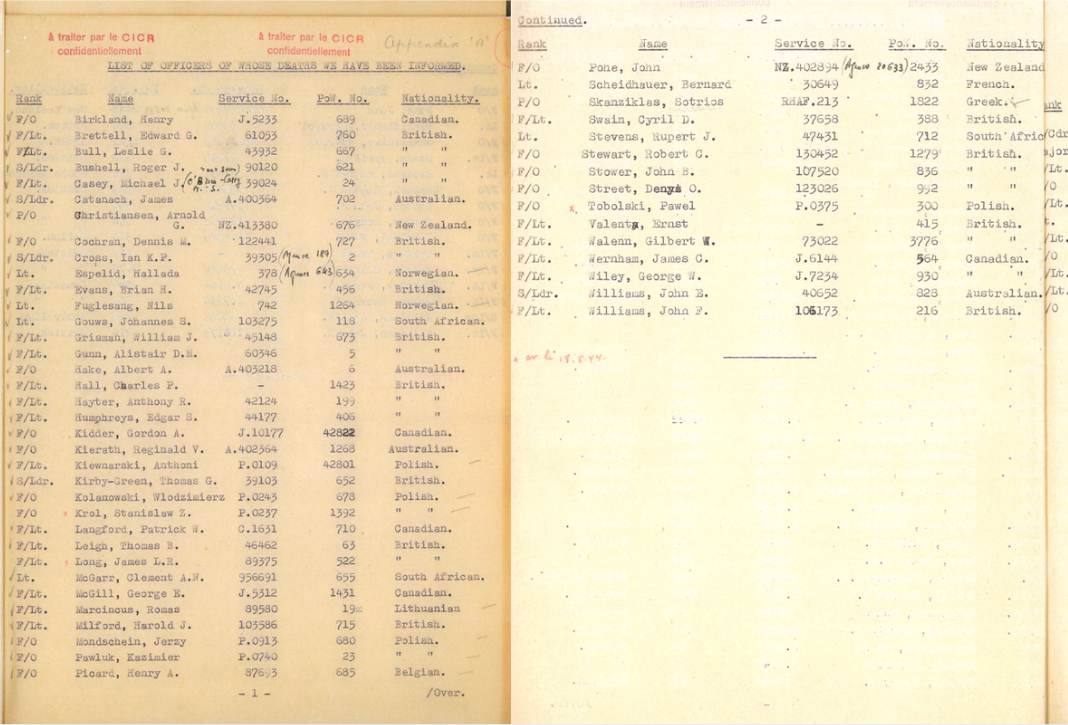

At 4:55 am, as the 77th man was getting out, a guard spotted the tunnel’s exit and sounded the alarm. Pursued by camp guards and the Gestapo, the fugitives who had made it out ran for the Zagan railway station, to escape by train. Borders were closed and a massive manhunt swept the region. Most of the 76 escapees were soon caught. The news sent Hitler into a fury, and he ordered that every recaptured man be shot. Only after Göring warned of Allied retaliation was the number reduced. Even so, 50 names were marked for death[10]. Among them was Roger Bushell.

List of executed prisoners, annex to the visit report of ICRC delegates to Stalag Luft III on 22 May 1944 (ACICR C SC, RR 808)

The prisoners were executed with a shot to the back of the neck during a transfer. The Germans later tried to justify the killings by claiming the men had attempted another escape, but no one was convinced. It was a blatant violation of the Geneva Convention. News of the massacre reached England only in May 1944, after a Protecting Power visit of Stalag Luft III.

Only three men managed to reach freedom: Dutch pilot Bram van der Stok, and the Norwegians Peter Bergsland (alias Rockland) and Jens Müller. Bram van der Stok’s journey through Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France took four months. He crossed the Pyrenees into Spain, reached Gibraltar, before finally arriving in England. Peter Bergsland and Jens Müller were free after just four days, traveling by train to Stettin and then by boat to Sweden.

The camp commander, Oberst von Lindeiner-Wildau, had a heart attack when the escape was discovered [11]. Removed from command, he was sentenced to two years’ fortress imprisonment. His successor, Oberst Braune, was reported to be extremely harsh by Protecting Power delegates after their 17 April 1944 visit. Discipline became particularly strict, and prisoner morale sank to its lowest point.

Download here an excerpt from the visit report of the Swiss Protecting Power to Stalag Luft III on 17 April 1944 (ACICR C SC, RR 864)

What the Law Says

The article 50 of the 1929 Geneva Convention relative to the treatment of prisoners of war strictly forbade the punishment of recaptured prisoners of war other than by disciplinary measures. Today the Third Geneva Convention relative to the treatment of prisoners of war, which replaced the 1929 Convention in 1949, contains similar provisions in its article 92.

The killing of the 50 recaptured airmen was a clear violation of the Geneva Convention, and it was denounced as a war crime by the British authorities as soon as the facts became known. In a statement in the House of Commons in June 1944, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden declared :

« His Majesty’s Government must (…) record their solemn protest against these cold-blooded acts of butchery. They will never cease in their efforts to collect the evidence to identify all those responsible. They are firmly resolved that these foul criminals shall be tracked down to the last man wherever they may take refuge. When the war is over they will be brought to exemplary justice. »

Since the order to kill the recaptured airmen came from the highest level of the German government, the Stalag Luft III case was included in the war crime charges before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg.

In addition to this high-profile trial, the Special Investigation Branch of the Royal Air Force devoted significant resources to finding those responsible for carrying out the killings. A painstaking effort to investigate the case led to the identification and indictment of 72 members of the Gestapo and Kripo. By then, some of the perpetrators were dead or presumed dead and some were never traced. 18 members of the Gestapo and Kripo were eventually tried in Hamburg in 1947. A secondary trial took place in 1948. While British policy towards Nazi war criminals evolved over time [12], and despite pressure to expedite trials as time went on, bringing to justice the Stalag Luft III case remained a priority, and one that the British public cared about deeply.

« The [Royal Air Force] appointed its Special Investigation Branch as an arm of that law—international law—which has suffered from a surfeit of advocacy and a damning dearth of enforcement. Enforcement was in this case so complete that its success virtually created an advanced point of principle through the qualitative change: international law can be effectively implemented—do not be diffident in drafting more where it is called for, and assigning effort to back it up » [13]

The Tale and Its Legacy: Hollywood Takes Over

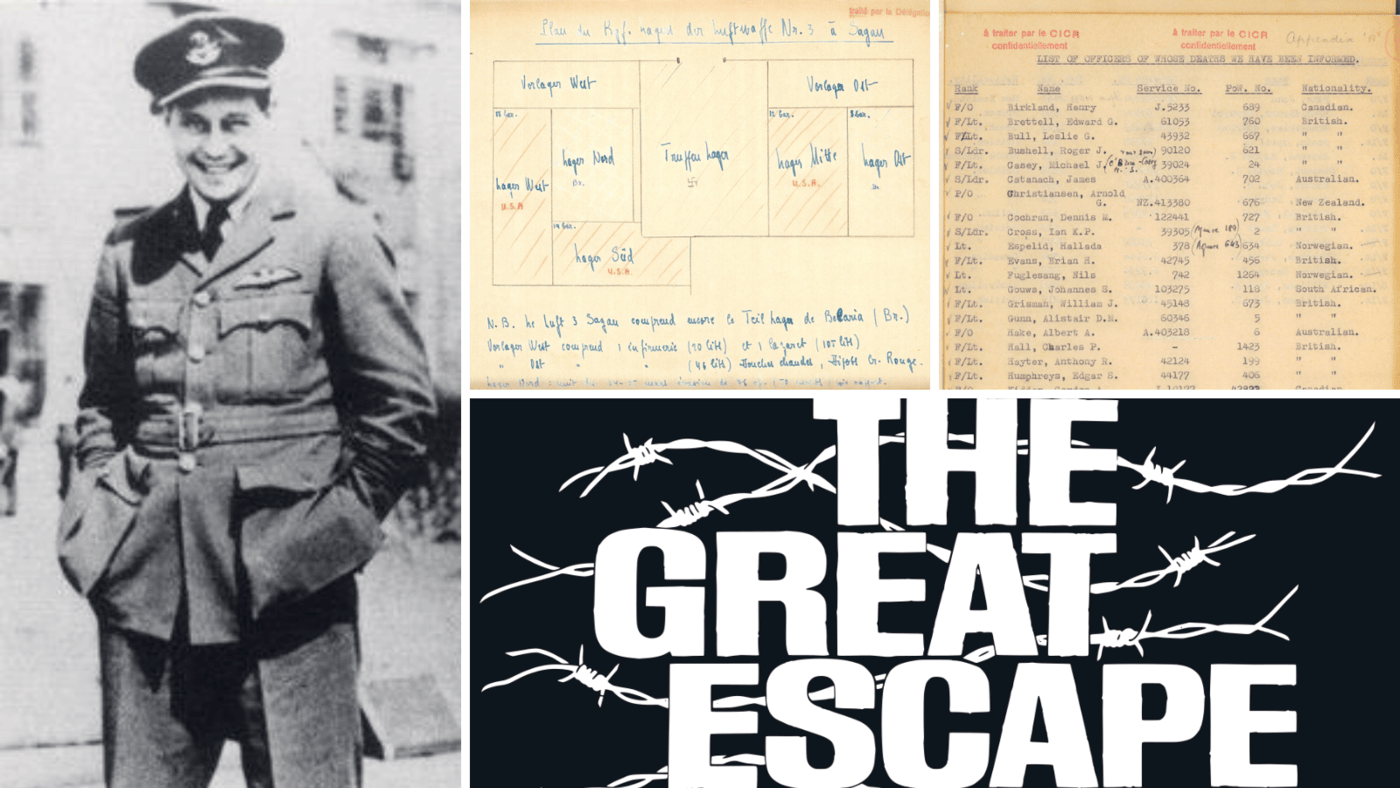

Official logo of the film “The Great Escape” (Wikimedia commons)

In 1963, the wider public discovered the story of the Stalag Luft III escape through John Sturges’s now-classic film The Great Escape. The cleverness and scale of the preparations were bound to catch Hollywood’s attention. With a touch of script polish, the prisoners’ courage, defiance, and hunger for freedom turned them into perfect heroes for the big screen.

The film was inspired by Paul Brickhill’s book of the same name, published in 1950. An Australian former prisoner of war, Brickhill had taken part in some of the preparations, though not in the escape itself (his claustrophobia prevented him from crawling through the tunnel). His book already took a few liberties with the historical record for mass appeal.

Once Hollywood took over, the story grew even more dramatic. Both the iconic motorcycle chase and the character behind the handlebars (Steve McQueen as Virgil Hilts) were pure invention. Including Americans among the escapees was also a Hollywood touch. In reality, only Commonwealth airmen and other foreign nationals serving with the RAF took part in the operation. With the exception of John Dodge, an American naturalized as British, the other American prisoners had been transferred before the escape.

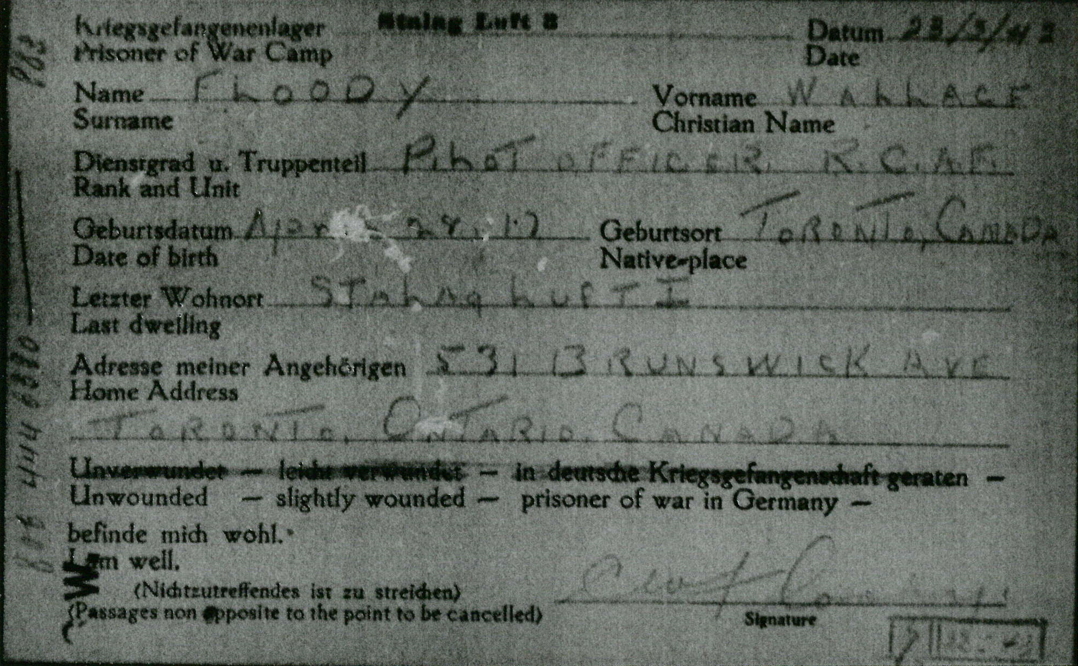

Capture card of Wallace Floody, ACICR C G2 GB, alphabetical file

The character of Roger Bartlett, however, played by Richard Attenborough, was directly inspired by Roger Bushell. Canadian fighter pilot Wallace Floody, who had used his experience in Ontario gold-mines to design the tunnels, was hired as a technical advisor for the film. Transferred before the escape, he was spared what befell Bushell and the others.

The Great Escape doesn’t rewrite the tragic fate of the majority of escapees. But, made for entertainment, the film chooses to end with the fictional Virgil Hilts recaptured but unharmed, leaving viewers hopeful for his next attempt. The film focuses on courage and heroism, not on the suffering of the prisoners or their execution. Its adventurous tone might feel at odds with the terribly grim reality. And yet, reading the words of Roger Bushell, who never gave up on his “travel plans”, it is tempting to believe he would not have minded such a legacy.

Further reading

Archives

- Sources on Roger Bushell in the Arolsen Archives

- Sources on the Great Escape in the Imperial War Museum collections

See also our research guide The ICRC during World War II

Scholarship

- Dana Polan, Dreams of Flight: “The Great Escape” in American Film and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2021.

- Allen Andrews, Exemplary justice, London : Harrap, 1976.

[1] ACICR C G2 GB 1994.045.00046, Correspondence between families and prisoners of war.

[2] ACICR C SC, RR 462, Report of the ICRC delegates’ visit to Stalag Luft III on 13 September 1942.

[3] The prisoners will have to dig deeper to avoid detection.

[4] ACICR C SC, RR 643, Report of the ICRC delegates’ visit to Stalag Luft III on 26 July 1943.

[5] ACICR C SC, RR 771, Report of the Swiss Protecting Power’s visit to Stalag Luft III on 22 February 1944.

[6] Ibid.

[7] ACICR C SC, RR 462, Report of the ICRC delegates’ visit to Stalag Luft III on 13 September 1942.

[8] ICRC delegates’ visit reports exist in two versions: the original, unedited version, which includes annexes and confidential information, and the edited version, sent to the warring Powers, which was corrected and stripped of annexes and confidential details.

[9] ACICR C SC, RR 643, Report of the ICRC delegates’ visit to Stalag Luft III on 26 July 1943.

[10] ACICR C SC, RR 808, Report of the ICRC delegates’ visit to Stalag Luft III on 22 May 1944.

[11] ACICR C SC, RR 864, Report of the Swiss Protecting Power’s visit to Stalag Luft III on 17 April 1944.

[12] See Priscilla Dale Jones, “Nazi Atrocities against Allied Airmen: Stalag Luft III and the End of British War Crimes Trials”, in The Historical Journal, vol. 41, no. 2, June 1998, p. 543-565, Donald Bloxham, “British War Crimes Trial Policy in Germany, 1945–1957: Implementation and Collapse”, in The Journal of British Studies, vol. 42, issue 1, January 2003, p. 91-118.

[13] Allen Andrews, Exemplary justice, London: Harrap, 1976

Comments