The COVID-19 pandemic, in the first half-year of its existence, has impacted the lives of most people on Earth in one way or another. It is the first truly global pandemic in modern times and each of us has been forced to grapple with its effects, both individually and collectively. The negative societal effects COVID-19 has wrought all over the world have, in many cases, been even more profound when viewed through the lens of persons with disabilities and these impacts have been aggravated even further in countries dealing with armed conflict.

Persons with disabilities living in conflict zones already deal with increased health challenges, exacerbated threats to their security, and societal marginalization that negatively impacts nearly every facet of their lives. In some cases, that marginalization comes from misconceptions that disability is somehow contagious and should be shunned; more frequently, though, it is the result of the broad assumption that persons with disabilities must be cared for and kept in restrictive environments for their “protection” — robbing them of basic dignity and the fundamental opportunity to explore and realize their personal potential. Though disability inclusion efforts have started to gain global momentum in recent years in several countries in which the ICRC’s Physical Rehabilitation Programme (PRP) operates, now — with the onset of the pandemic and its attendant social restrictions — persons with disabilities in these fragile contexts are at risk of being pushed even further to the periphery of their communities, potentially negating any progress that had been made.

While there are certainly very legitimate COVID-related health concerns specific to persons with disabilities – particularly those with physical disabilities that affect the immune system, lung function or other related factors that can put them at higher risk for serious complications – perhaps the bigger, less personally-controllable risks they face are related to the very seclusion from which they have spent so many years trying to break free. Just as they have begun to find the first tiny openings in their ability to access education or gain regular employment or even play sports, the isolation necessitated by the pandemic threatens to slam those doors closed once again. The real danger, though, is that the doors will remain closed even after the pandemic is under control because its imminent threat will have caused societies already reeling from the instability of war and conflict to forget about prioritizing the inclusion of persons with disabilities and building into their culture.

While there are certainly very legitimate COVID-related health concerns specific to persons with disabilities – particularly those with physical disabilities that affect the immune system, lung function or other related factors that can put them at higher risk for serious complications – perhaps the bigger, less personally-controllable risks they face are related to the very seclusion from which they have spent so many years trying to break free. Just as they have begun to find the first tiny openings in their ability to access education or gain regular employment or even play sports, the isolation necessitated by the pandemic threatens to slam those doors closed once again. The real danger, though, is that the doors will remain closed even after the pandemic is under control because its imminent threat will have caused societies already reeling from the instability of war and conflict to forget about prioritizing the inclusion of persons with disabilities and building into their culture.

For persons with physical disabilities, the ability to achieve economic security and independence has very often been a goal kept out of reach by a variety of societal assumptions about their ability – or inability – to reliably fulfill professional requirements, their perceived increased rate of health-related absences or a host of other preconceptions. Now, just as these misconceptions are starting to be proven wrong by persons with disabilities more often entering the work forces of their countries, the economic impact of the pandemic on the global and local economies could be devastating for their collective progress.

(File photo) A tournament co-organised by the ICRC and the South Sudan Wheelchair Basketball Association in Juba featuring the city’s first-ever women’s wheelchair basketball team. ©ICRC

What is necessary to stop this temporary barrier from becoming a long-term regression is the commitment from all sections of society – governments, employers, educational institutions, healthcare providers, among others – in countries all over the world to continue prioritizing disability inclusion efforts. This is not only essential to create opportunities for persons with disabilities, but it will also benefit societies, economies, business, etc., by bringing the vast potential of a population estimated at over 1 billion people into the fold. Many studies have shown that companies and organizations that prioritize hiring persons with disabilities have a positive impact on profits and better corporate culture. For example, U.S. companies that excel at disability employment and inclusion are four times more likely to deliver higher shareholder returns than their competitors, according to a 2018 study by Accenture.

In June 2019, the ICRC – in partnership with the Adecco Group Foundation – launched its new Career Development Programme (CDP) in an effort to push forward the economic inclusion of persons with disabilities. The CDP builds upon the success of the ICRC’s Disability Sport and Inclusion initiative, delivered as part of the PRP, which has already seen thousands of positive personal transformations, and seeks to create meaningful, lasting change in the way persons with physical disabilities are included in the labor market, specifically in countries dealing with persistent conflict and other forms of violence. Global CDP leaders train ICRC disability inclusion advisors in each country to become trainers themselves, focusing on teaching persons with physical disabilities how to identify potential careers that suit their background and experience, write resumés, build professional networks, develop interview skills, and build other competencies necessary to acquire employment.

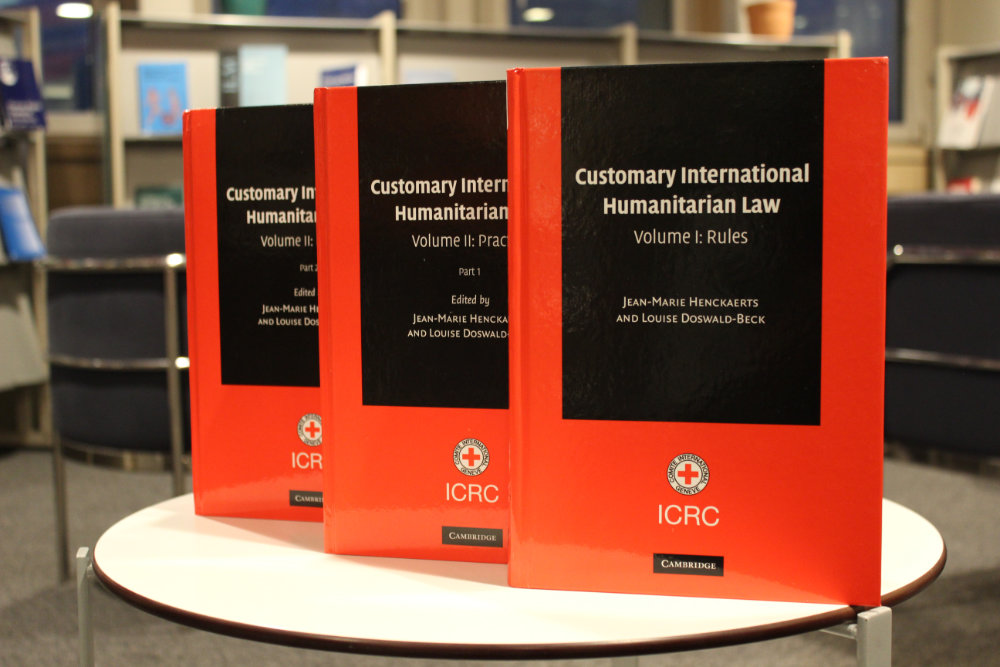

The CDP will evolve to further build the knowledge and acumen of these inclusion advisors over the coming years by including topics such as self-employment/entrepreneurialism, working with government representatives to develop and implement legislation specific to disability inclusion in the workforce, and partnering with educational institutions to create more accessible learning opportunities. But no matter how much knowledge the inclusion advisors bring to the table, the only way real change will happen is if they are supported by the commitment of the broader societies in which they work.

Disability inclusion will survive the coronavirus pandemic only if everyone believes it is a necessary social evolution and acts accordingly to support its growth. If this can happen, not only will people with disabilities transcend the societal impacts of COVID-19, but the communities, businesses, universities and organizations that push for their inclusion will grow and improve as well.

Editor’s note: This post was originally released on the ICRC New Delhi blog and is available at: https://blogs.icrc.org/new-delhi/2020/08/26/covid-19-and-its-impact-on-persons-with-disabilities/.

See also

- Rachel Coghlan, Palliative care, COVID-19 and humanitarian action: it’s time to talk., July 2, 2020

- Call by global leaders: work together now to stop cyberattacks on the healthcare sector, May 26, 2020

- Alexander Breitegger, Persons with disabilities in armed conflict, December 13, 2017

In these dark times it is a wonderful thing to read a blog post like this and to learn about the good work of people like Jess Markt and the organizations which support them – in this case the ICRC and the Adecco Group Foundation. The only people who can truly understand the hardships of disability are the disabled, and those who love and care for them. At the same time we can all easily see that any societal burden, whether armed conflict, or a global pandemic, or both, will be most painfully felt by those who are already struggling with the challenges of physical and mental disabilities. Bravo to the ICRC for reaching out to these people, the most vulnerable members of all human societies. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reminds us that the commitments of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, “to leave no one behind and to reach first those who are furthest behind”, require us to prioritize the vulnerable and marginalized of society. Thank you to the ICRC for taking these commitments seriously.

Thanks very much for your comment Philippe, and for your support!

This is why people are so scared on this virus. If you survive this virus, your lungs will not be the same as before.