From traditional media to social media, coordinated information campaigns or operations, the ways in which harmful information can enable or aggravate risks of harm for civilians during armed conflict are constantly evolving. However, evidence of risk factors remains incomplete, and solutions elusive.

In this post, Chris Brew, a former Protection Associate with the ICRC, looks to previous examples of harmful information (often referred to as misinformation, disinformation and hate speech or “MDH”) resulting in civilian harm to identify patterns in underlying risk factors to inform when and in what circumstances civilian harm may result from such information.

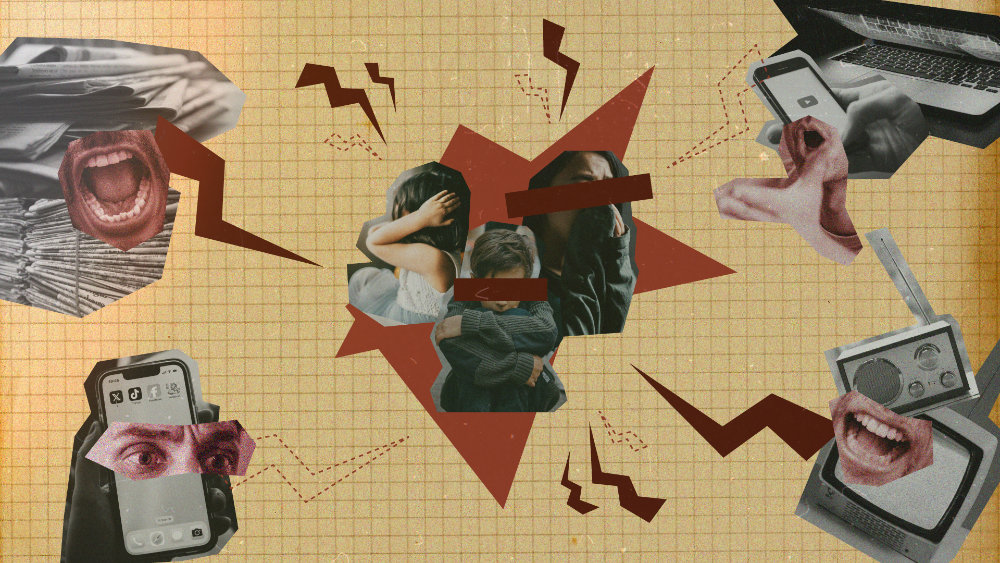

Harmful information has been an ever-present and evolving aspect of conflict and humanitarian action. As new technologies shape and reshape the ways humanity communicates, new channels emerge for harmful information to spread and overwhelm our ability to make sense of our environment and make timely and informed decisions. Whether through print, radio, television, or social media, harmful information can lead to serious harm to civilians and their ability to protect their safety and dignity. So, how do we move from identifying potentially harmful content to preventing and mitigating its negative consequences on people?

While it may be elusive to identify with certainty the causal links between the presence of harmful information and civilian harm, it is important to understand how the two interact. This piece seeks to identify a few entry points to engage the humanitarian, civil society, and policy communities in a broader discussion on relationships between content and harm to better inform risk assessments, prevention, and potential responses.

To do so, this piece utilises a desk review of events in six contexts composed of publicly available examples of harmful information. The analysis is based on observed patterns in underlying temporal and contextual elements that exacerbated the linkages between information and civilian harm. The reviews used are examples from Afghanistan, Armenia/Azerbaijan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Myanmar, and Syria.

Even in drastically different contexts, the broadening presence of telecommunications, rapidly increasing internet and social media penetration, political and social polarization, and a lack of trust in traditional media sources are major factors for information to potentially contribute to physical, psychological or other harms to people.

Through this review, six broad categories of risk factors have been identified: history of and/or ongoing armed conflict; history of and/or onset of polarization; restricted information space; propaganda and information operations; and limited content moderation.

History of and/or ongoing conflict

Human suffering during war is serious. Harmful information threatens to make it even worse. During a conflict, reliable and timely information can be the difference between life and death and the consequences of receiving inaccurate information or being overwhelmed by too much information can be immense. Unreliable information may prevent people from accessing safe places, cause them to evacuate using dangerous passages, or hinder their ability to access essential services or humanitarian assistance.

Each of the contexts reviewed have been affected by armed conflict within the last decade. Across those different situations, the presence of conflict can be understood as an overarching risk factor conducive to the emergence and spread of harmful information resulting in civilian harm, because of the polarization, distrust, surveillance practices, communal violence, hateful rhethoric and coordinated information campaigns that tend to be present in those contexts.

When a conflict becomes protracted, or an old conflict is used for a bulwark to create narratives to win political or social victories, truth can become impenetrable, societies can become more polarized, and harmful information permanent. In some contexts observed, harmful narratives are often evoked to stoke intercommunal violence for political gain.

History of and/or onset of polarization

Another overarching risk factor not only for harmful information resulting in civilian harm, but for armed conflict more broadly, is a history of or onset of societal divisions. Whether it be political, social, religious, ethnic or otherwise, polarization was visible in each of the six contexts observed for this review. Such polarization can result from a variety of factors including a history of conflict, displacement, competition over livelihoods, socio-economic inequalities, mass atrocities, historical grievances, communal violence, and/or political instability.

Polarized environments are both cause and effect of harmful information. In such an environment, where mistrust between different groups and communities is usually high, harmful information can easily move from rumors to violence. In multiple cases in the contexts observed for this review, false rumors fueled by severe grievances and divisions were the catalyst for the sharing of personal data of individuals based on ethnicity, and could result in lynching, the targeting and attacking of small businesses, incitement for the expulsion and killing of certain groups, mob violence, and hateful rhetoric directed at or by influential figures.

Restricted information space

Each of the cases analyzed is characterized by a restricted space for dissenting opinions and discourse resulting in an unhealthy information ecosystem marked by controlling narratives or restricted access to information. As we have seen on a devastating scale, one-sided public narratives that dehumanize individuals or groups can be a potent force for the incitement to violence.

Such restriction took place through a variety of means, including surveillance of protestors and opposition through social media, control of media and social media spaces triggering self-censoring, and repeated telecommunications blackouts and social media restrictions limiting the ability for people to receive access to life-saving information. These factors hinder people’s ability to contact loved ones and enable the spread of narratives affecting the safety or dignity of others. Such blackouts can also create a scenario where diaspora groups come to influence local and global narratives that can extend harm beyond the original context.

Propaganda and information operations

In five out of the six contexts analyzed, conflict dynamics and the resort to information operations by state and non-state actors for strategic purposes is another factor fueling the risks of harm for civilians. Such operations have long been part and parcel of armed conflict and are not illegal per se but can violate international humanitarian law. One of the ways they can increase the risk of civilian harm is through narratives which promote the dehumanization of an opposing group through hateful rhetoric, inflammatory language, and discrimination. In polarized and digitally connected contexts, such narratives can quickly spread and lead to violence by civilians against civilians. In other instances, narratives of victimization can be used to entrench and heighten pre-existing ethnic divisions, facilitate recruitment for armed actors, and justify later direct military action. In addition, harmful information in parallel to overt conflict can fuel distress, insecurity and anxiety, contributing to spreading fear among civilian populations.

Beyond information operations, coordinated online campaigns targeting the image or reputation of humanitarian organizations or medical workers can negatively impact their access and security, putting their activities and the much needed assistance they provide in jeopardy. Furthermore, the abundance of overwhelming and contradictory narratives can confuse, exhaust and silence civilians. Such silence combined with the ongoing presence of coordinated campaigns can further erode the truth, trust in institutional sources of information and limits the possibilities of victims to access the assistance they need to address traumas and other sources of suffering.

Limited content moderation

Finally, limited moderation of the social media space was found in three of the observed cases. In these contexts, online communities (particularly on social media platforms) were continuously used to circulate and spread harmful information and inadequate or insufficient moderation was available or provided. Such limited moderation made it easier for malicious actors to use platforms to incite fear and hatred and encourage violence against their opponents.

In most cases, limited moderation was combined with the rapid proliferation of social media adoption alongside the lack of digital media literacy skills to help discern fact from fiction. At the same time, actors often skillfully and cheaply used platforms and exploited the distribution methods on social media to spread content and advance their own agendas.

It is important to note that even in contexts where internet connectivity and social media use are limited, people are not insulated from harmful information and its effects, which often also grows organically from traditional media and information ecosystems. We should however note the potential increased risk to civilian harm when platforms become widely used with limited and sometimes slow safeguards to address harmful information.

Conclusion

As seen in every one of the cases reviewed, serious social, religious and/or political polarization, the presence of armed conflict, a charged information ecosystem, and a history of harmful information can severely heighten the risk of civilian harm resulting from the information space.

In some contexts, the rapid and inexpensive proliferation of telecommunications, internet, and social media can be coupled with limited digital media literacy and limited content moderation capacity and can increase the risk of harm. Though it is important to restate that digital access is by no means a pre-requisite for harmful information resulting in civilian harm.

Throughout these contexts, the most common channel through which harm seems to occur is the triggering of violence perpetrated by civilians towards other civilians. Contextual foundations combined with hateful rhetoric and fabricated or inaccurate information can quickly lead individuals and groups to take violent action against others. Sometimes this occurs through coordinated efforts by state and non-state actors, while other times it may emerge from more organic rumors, grievances and misinformation.

So as humanitarians, how should we proceed? Outlining risk factors is just one step of a much more encompassing response to stifling the ability of harmful information to cause civilian harm. A wider, more substantive and structured analytical prism of risk factors is needed to compliment an expanding evidence base for different examples or types of harm. Coordination response mechanisms are also needed to support coherent and complimentary actions across humanitarian, civil society, and international organization actors.

Patterns in risk factors where harmful information is most virulent can inform us of the likelihood of such information resulting in harms to civilians in future contexts. By being able to identify such patterns, humanitarian organizations, civil society, and policy makers will be better prepared to assess the potential for civilian harm resulting from information as we continue to adapt to technological advancements influencing modern warfare and communication environments.

See also:

- Joelle Rizk, Sean Cordey, What we don’t understand about digital risks in armed conflict and what to do about it, July 27, 2023

- Sandrine Tiller, Pierrick Devidal, Delphine van Solinge, The ‘fog of war’… and information, March 30, 2021

- Rachel Xu, You can’t handle the truth: misinformation and humanitarian action, January 15, 2021

Comments