The care pathway and the emotional window

For me, the best paediatric care is about continuity and co-ordination. This means following the care pathway from point of injury—where first response is vital in creating survivors—to resuscitation and surgery, through to post-operative care, to rehabilitation and beyond. Back in the UK National Health Service (NHS), I work in a paediatric major trauma centre and those are the principles that I apply today.

Equally important is the understanding of just how challenging the care of injured children can be to those entrusted with their treatment. Treating children can be overwhelming. Paediatricians talk about ‘the emotional window’: when you are treating a child who, for whatever reason, directly connects you at a deep, instinctive level with your own child. This sudden connection between being a medic and a parent accentuates the emotional impact and heightens your perception of the patient and their injuries. This can challenge the confidence of even the most experienced paediatrician. So, recognising it and moving forward to the next stage of the care pathway is an important part of anyone’s approach to this work.

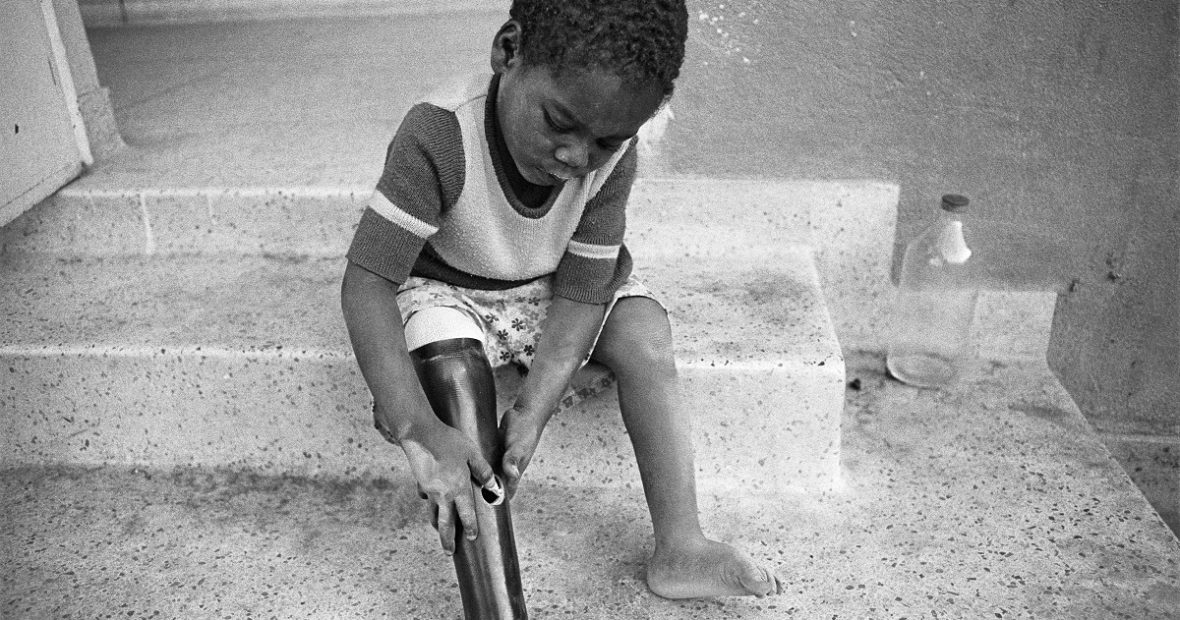

For me, one memory of this happening comes back particularly strongly. I’d been back in Camp Bastion on my third operational tour of Afghanistan and had just taken over the Emergency Department. We were pre-alerted to a severely injured child and were standing by for my first trauma call of that tour. The child arrived, and it was soon clear that she had suffered devastating injuries—she’d lost three limbs. As we examined her, I could suddenly see she was the same size as my (then) nine-year old daughter. She even had the same hair colour. Memories from home came flooding over me, suddenly mixed up with the now familiar sounds, smells, sights and the emotions of blast injury. I could have been overwhelmed. But then I remembered that had this child presented during my first tour some years previously, she wouldn’t have survived. We might not even have attempted to treat her. Thanks to the expertise we developed in our trauma systems since that time, this child did survive and was able to return to her own family. I often think about that child and how her life is now. Instinctively, you would assume that Afghanistan is not a good place to be an amputee, let alone a triple amputee, but there is no shortage of experience of amputees in the country and I’m hopeful that she has made progress in her life.

What does the future hold for the care of children injured in conflict?

This is a complicated question. While serving in the military, I did my best to champion the child, at times with mixed success. Paediatrics isn’t supported as a specialty by the UK Ministry of Defence. That said, there’s a growing chorus of people in both medical and defence circles who acknowledge the need for better preparedness to treat children in conflict. This is based not only on a deep desire to help these bystanders of war, but also on the experience and lessons that we gained from all our brave child patients.

Most importantly, we learned that existing trauma and care systems can be readily adapted to successfully treat children, even in quite tough circumstances. You don’t need paediatricians to treat children. You do, however, need to give specific, practical guidance to the non-paediatricians who find themselves with child patients. In these cases, a little can mean a lot, sometimes the difference between life and death.

A new Paediatric Blast Injury Partnership

Because I believe that we can give the best possible care to the child victims of conflict, I now co-lead Paediatric Blast Injury Partnership (PBI) initiative between Save the Children and the Centre for Blast Injury Studies at Imperial College London. The initiative is partnership of experts and institutions dedicated to improving the response to children critically injured by explosive weapons wherever they may be. We want to fill in the gaps in practice and in research. And, as I learned back in Afghanistan, their care requires continuity and co-operation by everyone dealing with their injury, sometimes lasting for the rest of their life. So, a key aim is to help increase awareness of the complexity and long-term effects of blast injury on children. This is the first organisation in the world to specifically focus on the challengesof paediatricblast trauma. Our Partnership will be vital if we are to improve outcomes and make sure that what we’ve already learned doesn’t go to waste.

‘A little book’—The PBI Field Manual

When the Partnership was formed we agreed that we wanted to get on and make a difference quickly. So in addition to drawing together strategic thinking about the problem, we decided that our first priority would be to do something practical. During our inaugural workshop in December 2017 Malik Nedam Al Deen of Syria Relief spoke movingly, but also pragmatically, about what he needed to make it easier for medics like himself in Northern Syria to treat children with blast injuries. At one point he said, ‘I just need a little book to give to our clinicians, so they can see how to adapt what they know for adults to children—just a little book’.

So that’s what we decided to do in our first project as a partnership. We are creating ‘a little book’—a field manual—for Malik and everyone else in conflict and post-conflict zones to help them treat blast-injured children. Our PBI field manual will be a pragmatic framework to enable paediatricians without trauma experience or trauma clinicians without paediatric experience to structure their care of blast injured children. It will turn guesswork into transferable skills at the moment where they are needed most. It will follow the care pathway from point of injury to rehabilitation and beyond. It will enable clinicians to look after severely injured children with some direction and confidence that they are doing the best they can. It will enable continuity and cooperation. It will address the physical and psychological needs of the child, encouraging the caregiver to consider the whole child and not just the injury.

Because we don’t want it to be a reference book that gets put on the shelf and forgotten, we’ve taken care to make sure it will be really clear to read, portable, robust and usable in field conditions. Our printer recently summed it up—‘it’s going to be tough and handy’. We also remember the emotional demands being made on the people using the manual. So, we intend for it to give confidence to health care workers, to help them overcome the heightened anxiety that can paralyse decision-making when they are confronted with the reality of injured children.

None of this is easy, but it is another memory from Afghanistan that gives me hope. A young boy arrived at our emergency department in traumatic cardiac arrest as a result of chest trauma and blood loss. Some clinicians may still hold the perception that this was un-survivable. But five days later he was kicking a ball around the ward. Managing traumatic cardiac arrest is the pinnacle of performance for a trauma team. The impact of that kind of success floods the unit and buoys it for days despite all the negative experiences of war. We owe it to him and all the other amazing children who are fighting to survive today and tomorrow.

***

Dr Paul Reavley is currently a full-time NHS consultant at Bristol Royal Infirmary and Bristol Royal Hospital for Children. He is President, Emergency Medicine Section, Royal Society of Medicine and Consultant Paediatric Emergency Medicine. He was a medical officer in the British Army for 18 years. Paul is one of the leads in the Paediatric Blast Injury Partnership and director of the Paediatric Blast Injury Field Manual project. When he isn’t working, he is obsessed with baking bread, in particular sour dough—another lesson he learned in Afghanistan—that pulling fresh bread from the oven and sharing with colleagues was a unifying and fortifying experience. As with trauma care, the satisfaction of achievement with a good loaf never fades.

DISCLAIMER: Posts and discussion on the Humanitarian Law & Policy blog may not be interpreted as positioning the ICRC in any way, nor does the blog’s content amount to formal policy or doctrine, unless specifically indicated.

Comments