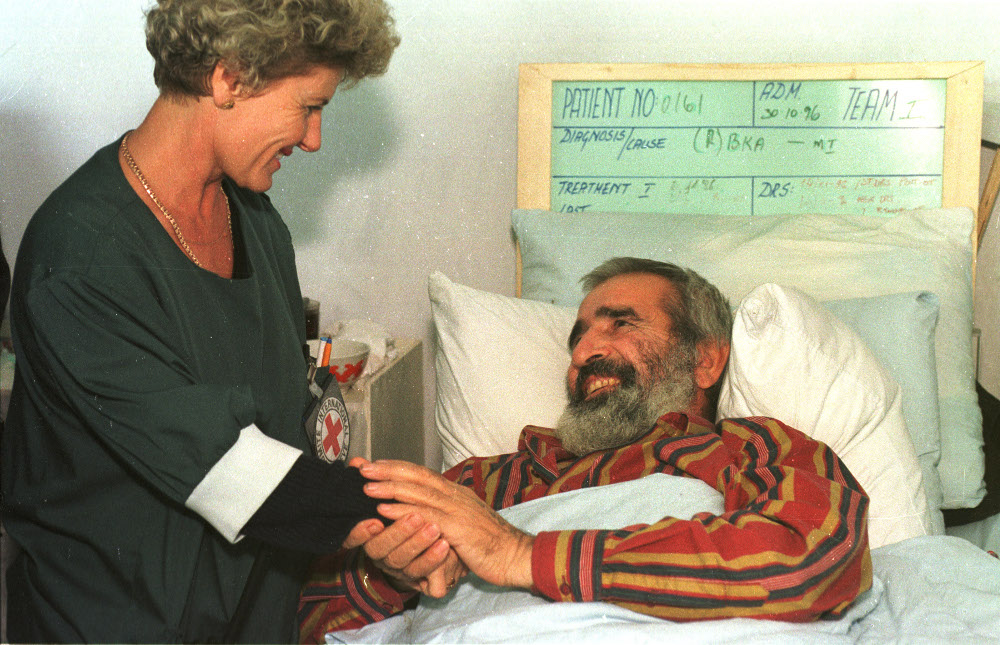

In this personal story told by a former head of office at the ICRC surgical hospital of Novye Atagi, Chechnya, a short, violent encounter leads to a long journey of recovery.

These are selected excerpts of an opinion note written by Christoph Hensch published by the International Review of the Red Cross for the 20 year-commemoration of the attack on an ICRC surgical hospital in Novye Atagi on 17 December 1996.

***

In October 1996, I was appointed Head of Office at the ICRC war surgical hospital in Novye Atagi, a small Chechen village south of Grozny in the very south of the Russian Federation. The ICRC had opened the hospital here on 2 September 1996 in order to care for the war-wounded in the Chechen conflict. For security reasons, we were almost exclusively confined to the delegation compound, and a humming social life developed among those who worked and lived there.

In the early hours of 17 December 1996, two and a half months into this mission, everything changed.

When I woke up that morning, I could see a few strips of light reflecting on the wall, the streetlight from the courtyard shining through the blinds. There were also the sounds of voices and what seemed to be banging noises.

I felt a sense of dread. Not knowing what I should do, I sat up in bed and started pulling on a pair of trousers. Before I could finish putting them on, the door opened and a dark figure walked into the room. In the dim light I perceived a person with a military-style jacket and a black balaclava on his head. I lifted up my hands to about shoulder height and said something like, “OK, OK…”

Looking at the person, the next thing I saw was him pulling his right hand out of the pocket of his jacket, and pointing a gun at me – then and a red-and-yellow flash of light erupted. Almost instantaneously I felt a piercing pain in my shoulders, seemingly hot and cold at the same time. Instinctively I moved my hands to where the pain was, letting myself fall back onto the bed, turning to the wall. When nothing happened immediately, and I couldn’t think of any successful course of action, I remembered to calm my mind, and I started a simple meditation routine, repeating a short mantra and simply resigning myself to go with the flow of whatever might happen.

Slowly my intense awareness of my surroundings started to weave together, as the radio sprung to life with voices calling out, at random at first, but soon connecting in exchanges and conversations. Gradually the horrific proportions of the massacre of international medical personnel at the Novye Atagi hospital, who were murdered intentionally and in cold blood, became apparent. It was only then that I realized the assailant had intended to murder me too but had left me for dead, and that I had miraculously survived the ordeal.

***

That day, six ICRC delegates were shot dead in cold blood by unidentified gunmen in their quarters at the hospital in Novye Atagi. Their mission had been peaceful and humanitarian. They were:

Fernanda Calado, an ICRC nurse of Spanish nationality,

Fernanda Calado, an ICRC nurse of Spanish nationality,

Hans Elkerbout, a construction technician seconded from the Netherlands Red Cross;

Hans Elkerbout, a construction technician seconded from the Netherlands Red Cross;

Ingeborg Foss, a nurse seconded from the Norwegian Red Cross;

Ingeborg Foss, a nurse seconded from the Norwegian Red Cross;

Nancy Malloy, a medical administrator seconded from the Canadian Red Cross;

Nancy Malloy, a medical administrator seconded from the Canadian Red Cross;

Gunnhild Myklebust, a nurse seconded from the Norwegian Red Cross;

Gunnhild Myklebust, a nurse seconded from the Norwegian Red Cross;

Sheryl Thayer, a nurse seconded from the New Zealand Red Cross.

Sheryl Thayer, a nurse seconded from the New Zealand Red Cross.

This is the story I usually tell when someone asks about what happened. Many other people will have a story from that day. Some have an up-close experience of the event, while many more were touched from afar. Each of these stories is unique and worth listening to.

***

I have another story to tell, one that is closely linked to the one above, and which is just as important. It is a much less sensational story. It is drawn out, long, difficult and seemingly without end. It is the story that began the moment the first story finished, the story of recovery and healing. It is a journey during which I travelled in the dark for a long time, left entirely to myself to make sense of what I had experienced; one where I certainly learned a lot, yet whose purpose long escaped me. When I think and talk about this story, I feel vulnerable and it seems to be very self-centred. It was difficult to find a helpful community that would support me.

Today I feel strong enough to share this story. This story is important because many humanitarians experience trauma and while I cannot speak for others, connection (or lack thereof) with my group and community has been the recurrent and defining theme of my journey of healing and recovery.

Looking back, I realize how helpful a collaborative approach to healing from trauma could have been for me. On 17 December 1996, I was part of a group and community that felt like a big family: the ICRC. That community, as a collective, suffered a trauma as well on that day. It was an unprecedented and unprovoked act of violence against the organization and its workers.

Whenever I speak up I sense a resistance, like an invisible barrier going up… Maybe this is because it does touch a nerve in so many humanitarians. How do we reconcile our personal feelings with the imperatives of the humanitarian and organizational mission and principles?

While I progressed in getting back my physical health, the effects of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) seemed to arise more often. At unexpected moments my body reacted to triggers, although seemingly without cause: breaking into a sweat, blocking my ability to talk without becoming emotional, feeling an unexpected loss of energy, shaking, and so on. The most difficult time of the day was going to bed, falling asleep and letting go of control, because it was during the night that the trauma had happened. How could I sleep without locking the door, or without listening to the sounds in the corridor, or elsewhere in the building? However, once I did fall asleep, I seldom dreamed about the event. The effects of PTSD can be extensive, are individually different, and have been well documented. Without help, this is a difficult part of the journey to navigate. It was only much later that I decided to seek professional help, and it was even further down the path that I started to perceive it as a learning and healing journey.

My journey and that of the organization seemed to move on parallel lines, and as in a true parallel, the lines did not touch except at certain specific events. There was very little time invested in helping each other to understand what was happening and making sense of that horrific event. Very little time was spent walking next to each other, supporting each other. Individuals have to live their journey by themselves – and the collective deals in its own way with traumatic events that impact it, although the collective is ultimately made up of individuals with their own personal feelings and experiences. I know very little of how the collective (meaning the ICRC as an organization) dealt with the shock, the pain and the trauma of Novye Atagi, for example.

I do not make any claim to special treatment because I was a “victim” or “survivor”. I suspect that there are many Red Cross delegates who have had horrific and traumatizing experiences during their career. And I suspect as well that they also need a sense of belonging to the wider community on their journey of recovery. How is the ICRC living up to its responsibility to be the community that helps the individual regain his or her health and humanity?

I do experience a great reluctance by the organization to engage in any activity that looks at the deeper emotional and spiritual hurt that is caused by the violence witnessed and experienced in the field. Whenever I speak up I sense a resistance, like an invisible barrier going up, as if there is a great reluctance to hear my voice and as if people do not want to look at this side of the humanitarian action coin. Maybe this is because it does touch a nerve in so many humanitarians. How do we reconcile our personal feelings with the imperatives of the humanitarian and organizational mission and principles?

***

Humanitarian work is inherently stressful. People working in the sector are sometimes exposed directly to traumatic events, but more often indirectly. Indirect exposure is also known as vicarious traumatization. According to studies, humanitarian aid workers have a much higher occurrence of PTSD than the average population. Up to 30% of aid workers suffer from PTSD in different ways. The effects of PTSD can arise weeks, months or sometimes even years after the initial experience.

There are many different possible ways in which the impact of violence on aid workers can be addressed, and in my opinion we have come a long way over the last twenty years in terms of the awareness of that impact as well as the variety of methods available. However, there is no one solution that fits all. We all tend to solve challenges from particular points of view corresponding to our own standpoints, and can overlook alternatives which can add to the effectiveness of already existing measures. While these methods are all different and sometimes seem contradictory, they are all necessary and could provide a rich set of responses, complementing each other. Similar support mechanisms are also advised for people working in natural disaster response, as suggested in a study by Jolie Wills from New Zealand Red Cross.

In the opinion note that I wrote for the International Review of the Red Cross, I propose an approach to psychosocial support provided to aid workers that could best be described as integral or holistic. It has the following components, which are described in more details in the note:

- objective support through professional services;

- adaptation of the systemic environment;

- an aware and caring organizational culture; and

- enabling the subjective experience.

An integral approach to dealing with stress, burnout and trauma should become a standard operating principle in the humanitarian sector for employers in dealing with their workers. Employers in the humanitarian sector should create and implement collaborative processes and become conscious and proactive partners in the healing journeys of their staff who have been impacted by injury and trauma while working for the institution and on behalf of humanity as a whole.

Related

- Christophe Hensch, “Twenty years after Novye Atagi: A call to care for the carers“, International Review of the Red Cross (upcoming edition), December 2016.

- Profiles of the six ICRC staff killed in Chechnya, December 1996.

- Speeches by Cornelio Sommaruga at the repatriation of the mortal remains at Geneva Cointrin airport, and at the funeral ceremony in Cathédrale St-Pierre, 18-20 December 1996.

I was there. I knew them all. I packed their belongings after the killing and sent them to their families.

I saw their autopsy Pictures. I said good by to them.

But every year when Christmas approaches, the week before on 17. December , I do think of them. I remember the day it happended and even more the weeks before when we did our Job there… Caring for People, Setting up a hospital, working and living together. Laughing together.

I do hope that mankind is able to learn. And that we forget the words of guilt, hatred, jealousy, greed and many others. I do hope that we learn to live in societies where, if not love, but at least respect is ruling the interaction between cultures and individuals alike. There is plenty of space for hope…

Andrea

Thanks very much for these reflections in such an important area. I think it is a vital show of health to seek support rather than pretend we don’t ourselves need help when we are traumatised.

Dear Christoph, Thank you for your article……..I still miss Hans Elkerbout…….he was my friend……..I knew him for years……….it is good that in some loyal heart his memory together with the memory of the other 5 nurses who died in this massacre, remain enshrined forever…….God bless us all………Thank you

Dear Christoph, I thank you for your courage to memory this bloody masacre. I myself I do carry

Fernanda Calado deap in my heart. She was and is my beloved friend.

The rules of International Red Cross in Geneva dictated that I am not allowed to connect anybody than medical stuff to talk about this big loss – as a translator and interpreter of ICRC I met Fernanda in Pakistan in 1991/1992. My social life I am bound to carry out in Germany. But here in this developed country authorities and even medical doctors even as experts refused – and still refuse – to pay regard to my pains of loss.

I thank you that you still remember . . . So I am not alone.

Best regards Martin

RIP

IT was a horrible time . At that time (1996,before Rwanda invade Congo.) I was warking with the international red cross in Congo in kajembo refuge camp,not far from cibitoki .

More details about that horrible situation red UN mapping report on YouTube or Google or on UNHCR .thank you