If the international community clearly sees the importance of “Putting people at the centre”, it seems less ready to do so. Here’s a brief guide for humanitarians who feel it’s time to use digital communication technologies to help communities build resilience. In the end, this is about shifting our mindset from saviours to enablers.

In 2008, the IFRC stated “people need information as much as water, food, medicine or shelter. Information can save lives, livelihoods and resources. Information bestows power.” Fast forward to 2012, the BBC reports “it may now be the humanitarian agencies themselves – rather than the survivors of a disaster – who risk being left in the dark.” Looking at the conversations scheduled at the World Humanitarian Summit (such as the special session on “Putting people at the centre”), the international community seems to grasp the importance of placing communities at the heart of humanitarian operations. Recognizing affected populations as primary agents of response is seen as a means to facilitate emergency response and develop longer term community resilience.

Yet, at a recent workshop at the Tech4Dev conference, we posed the question “Are we ready to shift the power to communities” to a room full of humanitarians. The result? A room full of enthusiasm to make the change, but hesitation about being ready to.

The challenge of understanding how communities respond to crisis is a complex one, with no “one size fits all” solution. And as technology evolves and integrates into daily life, we are witnessing a whole new subset of behaviours, expectations, risks and opportunities. From the use of drones to help communities prepare for crisis, crowdsourcing digital mapping techniques to respond to crisis, tapping into mobile phone subscriptions to track displaced populations, the digital revolution has exposed a variety of tools creating new opportunities for humanitarian responders.

INTRODUCTION TO CITIZEN DRIVEN RESPONSE NETWORKS

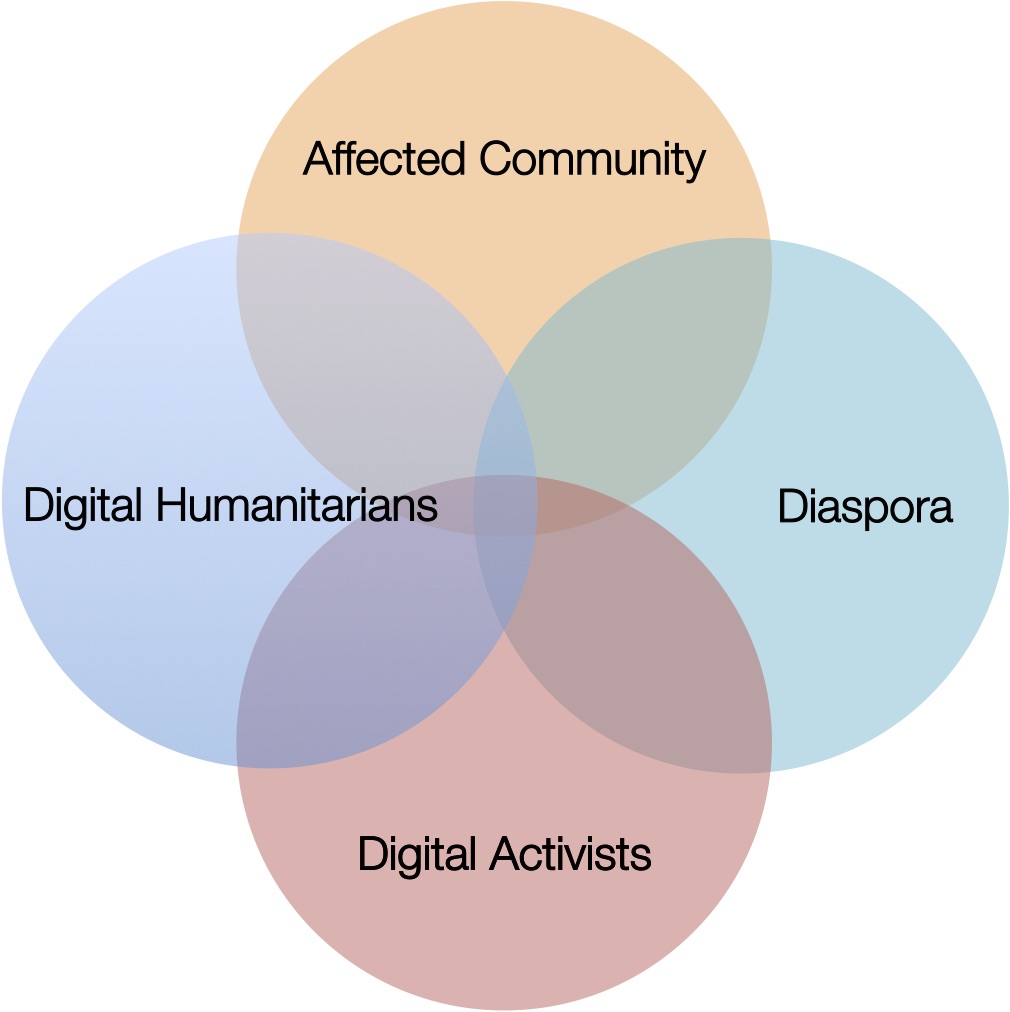

In a crisis situation, citizens leverage technology to react through four main types of online networks: affected communities, diaspora, digital humanitarians and digital activists (Figure 1). These networks exist for the purpose of seeking help, providing help, or a hybrid of both. They consist of individuals, organizations, local community groups, ad-hoc virtual communities, networks of networks, and the list goes on. Some activate during crisis, some transform, and others emerge, ad-hoc, temporarily for a specific purpose and separate soon following.

Figure 1. Citizen Driven Response Networks from Phillips (2015)

Networks in need

There are two primary networks that seek help during a crisis.

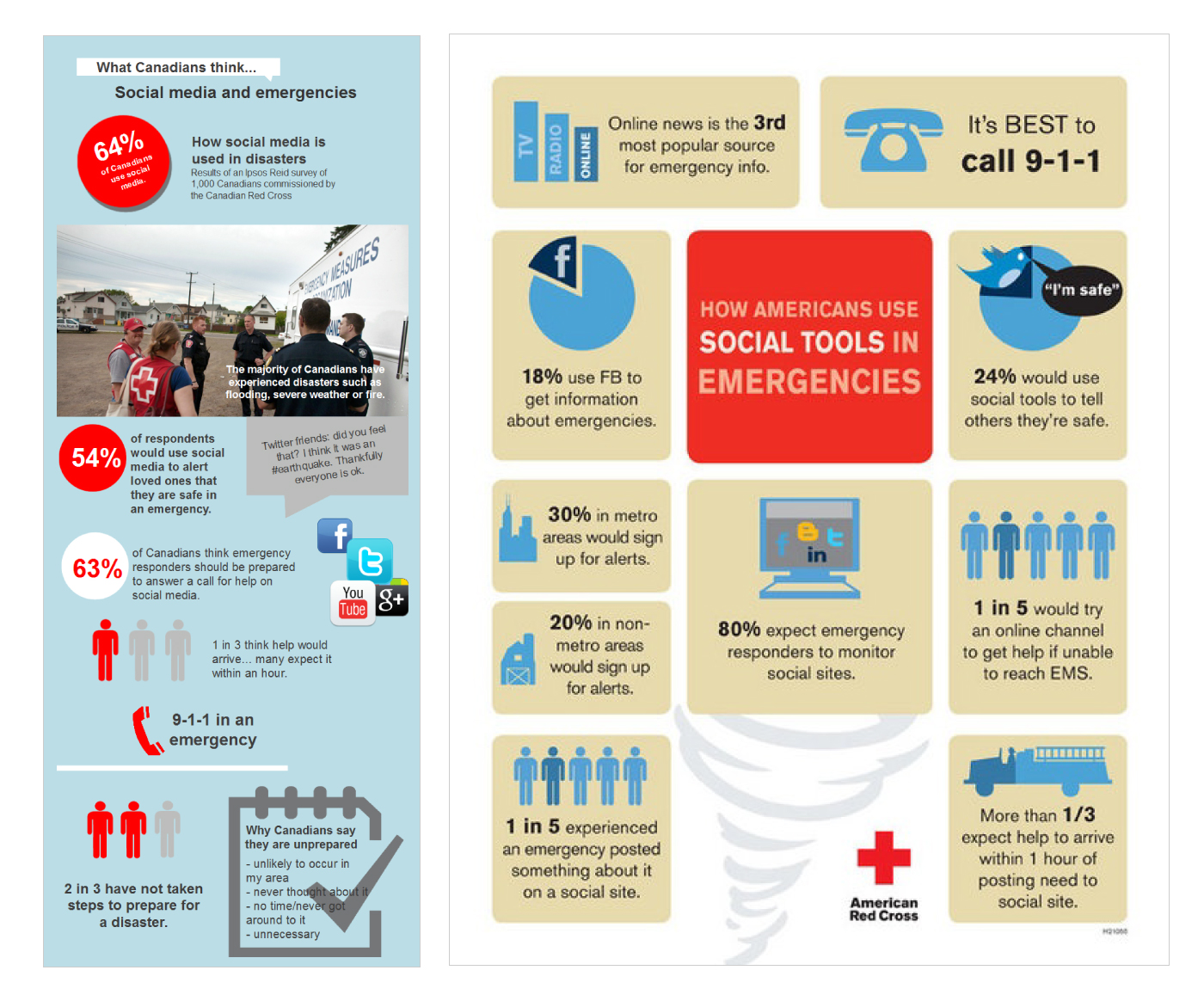

Affected communities consist of actors physically located in the area impacted by crisis that leverage technology as a means to solicit help. Whether assistance is needed locating a missing relative, extracting someone trapped from an earthquake, identifying evacuation points or shelters, or acquiring food or water, citizens post calls for help or requests for information to social media channels. As depicted in Figure 2, the American Red Cross and the Canadian Red Cross reported up to 80% of social media users expect emergency responders to monitor social media sites, and that 1 in 3 expect help to arrive within one hour of posting. In the US, 1 in 5 who have experienced an emergency have posted about it. In Canada, 2 in 3 have not taken steps to prepare for emergencies.

Diaspora communities consist of actors closely tied to the affected community, but situated outside the zone of impact i.e. friends and family living abroad also resorting to social media for their requests. In instances where help is needed, they may also generate online calls for assistance locating lost loved ones, or post on behalf of contacts on the ground whom they may have been communicating privately.

Networks for support

In terms of support, there are many ways people mobilize to provide help online prior to, during and after crisis situations.

Both affected and diaspora networks also serve as support networks. Primarily, they act as a tremendous resource for information about the local context, e.g. by providing contextual information that is missing or insufficient, and insights into local cultural, political, religious practices; by identifying local risks, highlighting areas more affected than others, and report activities of other response groups (e.g. another NGO that set up a food distribution point). They are the local eyes and ears that supplement this remote and freshly deployed response, and their capability is unprecedented. As a few examples: in 2007 during the Virginia Tech school shootings, people worked together online to identify the list of disaster victims (generating a 100% accurate list of names within less time than official release of names); in the 2010 wildfires in Russia, citizens organized to create a “self-help map” to coordinate resource requests with offers.

Diaspora communities are a more particular and available resource as they are remote from the crisis and more willing to help. Haitian diaspora networks, for example, where very involved in the translation of materials and information during the Haiti Earthquake in 2010. They can also serve as a source of financial support during the acute phases of a crisis.

Digital Activists Networks (DAN)

From documenting human rights violations, innovating new technologies, and, in more extreme cases, taking digitally punitive measures against questionable actors, Digital Activist Networks (DANs) focus on the advocacy component of crisis. From citizen journalists to slacktivists, information activists to hacktivists, their activities manifest through different personas. Although outside the scope of this discussion, it’s worth noting that in many cases humanitarian operations are inherently political. DANs and DHNs (described below) often times are not mutually exclusive, but overlap. Occupy Sandy for example, which coordinated supplies for disaster victims during Hurricane Sandy, was a network of Digital Activists from the Occupy Movement who transformed for a humanitarian purpose. As we proceed, it’s important we consider these overlaps in collaboration and also risk planning.

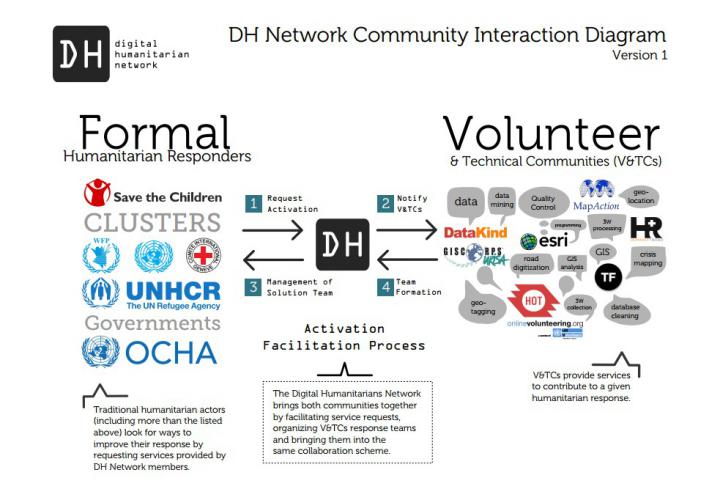

Digital Humanitarian Networks (DHN)

As I described, Digital humanitarians use technology to provide “…aid and action designed to save lives, alleviate suffering and maintain and protect human dignity during and in the aftermath of emergencies.” They respond to, manage and analyse the surge of big data, or big (crisis) data – a termed coined by Patrick Meier in his book Digital humanitarians – during a crisis.

With more data on this planet than grains of sand, big data poses a challenge to organizations on a normal day. During a crisis, the amount of information generated sky rockets. During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, for example,16 000 tweets were being generated per minute, social media usage increased up to 25% during the Thailand floods, and 300 000 tweets were being generated per minute during the Japan earthquake and tsunami in 2011. In addition, similar to some digital activist ventures, DHNs also innovate through: technology developing emergency response platforms, e.g. Ushahidi crisis mapping platform or Sahana information management software; developing apps for translation or crisis reporting; generating and providing funding; aggregating supplies, among other things.

Bridging local and global

In a crisis, humanitarian responders are challenged with gathering situational awareness, identifying needs are of the local population, identifying key focal points in a community, responding to digital requests for help and information, mapping areas, acquiring donations, risk planning risk and adopting digital security measures, etc. Supplementing humanitarian efforts with citizen driven response networks can facilitate addressing and overcoming some of these challenges.

How does that work? One way is to develop and/or support the development of local Digital Response Networks (DRN). As Andrej Verity and I suggest, local DRNs can build the overall resilience in communities by enhancing collaboration, coordination and situational awareness. DRNs are network hubs that bridge the physical response community (e.g. local first responders, government, community leaders) with local and global digital responders. DRNs serve the potential to build capacity and shift the power from the global to the local, while simultaneously providing a focal point for local and international humanitarian responders to coordinate, collaborate, and enhance operations to achieve greater impact.

Through initiatives like developing larger DRNs, and taking the time to learn about and forge relationships with the networks that exist, emerge and transform during crisis, a window of opportunity opens for enhancing crisis response and building broader resilience in our own operations and in the communities we serve.

As humanitarians, we should work towards understanding and empowering the existing capabilities enacted by citizens during crisis. Cooperation and collaboration is already happening offline and online, and our goal should be to leverage this change. Consider innovation not just about creating, but also facilitating.

We must, in the end, shift our mindset from saviours to enablers.

Jennie Phillips is a Doctoral Fellow with the Citizen Lab, University of Toronto.

Comments