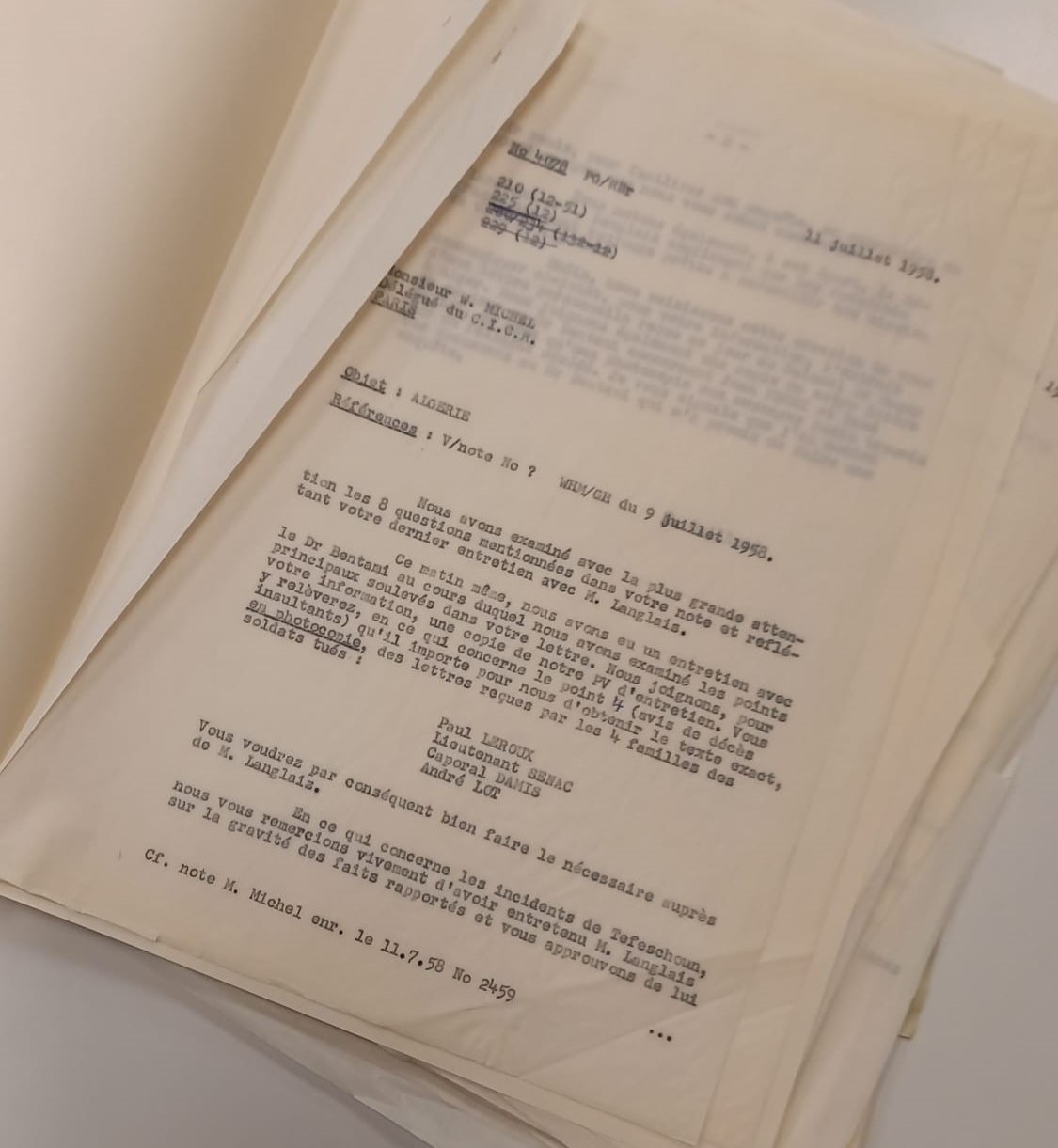

In the absence of digitised copies, researchers must work with original documents. Consulting original archive documents provides privileged access to historical sources. It makes us aware of the history of the document’s transmission, and can sometimes be very moving. However, consulting original documents requires special precautions. Archives are unique and often irreplaceable. Any alteration to the documents therefore constitutes permanent damage to the archive collection being studied.

Since they were made available to the public, certain archive references have been ordered very frequently in the reading room: during these consultations, these archives have suffered numerous micro-alterations at the hands of readers.

This article is a necessary addendum to the reading room rules. It is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather aims to provide some additional information about the physical condition of the collections. First, we will address issues related to the conservation and preservation of documents. Next, we will discuss best practices for consulting documents in the reading room. Finally, we will examine the extent of alteration in the archives.

Preservation and packaging of archives

A matter of chemistry …

An older model of archive box without an alkaline buffer, the yellow discolouration on the label shows the acidification of the paper over time. ACICR

Preserving archives is primarily a question of material chemistry. Indeed, preserving archives over time requires consideration of the chemical characteristics of the written media being preserved. At the ICRC archives, we mainly preserve paper, cards and cardboard, photographic paper and film, as well as some leather artefacts and textiles. Our collections are not very old and we have no materials dating from before the 18th century. The ICRC archives therefore contain no parchment or papyrus! Even though the ICRC’s collections are fairly recent, some items remain particularly fragile: newspaper, for example, ages very badly.

Paper is made from plant fibres and is mainly composed of cellulose. However, it often contains another molecule, lignin, which contributes to the acidification of the paper. The acidification of collections is one of the main dangers facing archives: it makes the paper less flexible and much more brittle, which increases the risk of tearing. As it oxidises, lignin also tends to yellow the paper, which can alter drawings and other pictorial works. The acidification of paper is a phenomenon that is difficult to control: in reality, we can only slow down the process, but we cannot really stop or reverse it.

… and mechanics!

Example of carbon paper that has been particularly badly damaged. Damage of this kind requires the documents to be sent for restoration. ACICR

Preserving archives is also a matter of mechanical constraints: collections must be stored in such a way as to limit creasing, rubbing, tearing and deformation. A true ‘star’ of 20th-century archives, carbon paper, nicknamed onion paper, is particularly sensitive to mechanical damage. Carbon paper, which is particularly light and thin, was used in bundles of several sheets placed behind a document in typewriters. It enabled the production of multiple copies that were distributed to the various recipients of a letter or report. Carbon paper is quite temperamental: it is light, sensitive to static electricity and creases very easily.

When folded or creased, the only way to restore it to its original shape is to iron it lightly with specialised conservation equipment.

Preservation equipment

These chemical and mechanical constraints require archives to equip themselves with conservation and preservation equipment. This equipment ranges from large-scale infrastructure to ‘small items’ used for conservation. The ICRC archives have several compactus systems – mobile shelving on rails – in rooms that are monitored to maintain a temperature of around 20°C and a humidity level of around 50%. These rooms are monitored and ensure that the materials are well preserved. The archives are placed in boxes with specific chemical characteristics: these cardboard boxes have an alkaline reserve and slow down the acidification of the paper. Inside these boxes, the bundles and files are stored in envelopes, covers and pockets that also have an alkaline reserve. This ‘small equipment’ is designed to protect the documents from excessive acidification. In the most traditional box models, the files are kept upright, sometimes using wedges to prevent the documents from becoming distorted over time.

This work of preparing the archives is called conditioning or reconditioning. It is meticulous and delicate work that requires great attention to detail. Conditioning a series of archives measuring several dozen metres can take an archivist-restorer several months to complete.

Guidelines on the consultation of archives

Nothing that could stain the documents

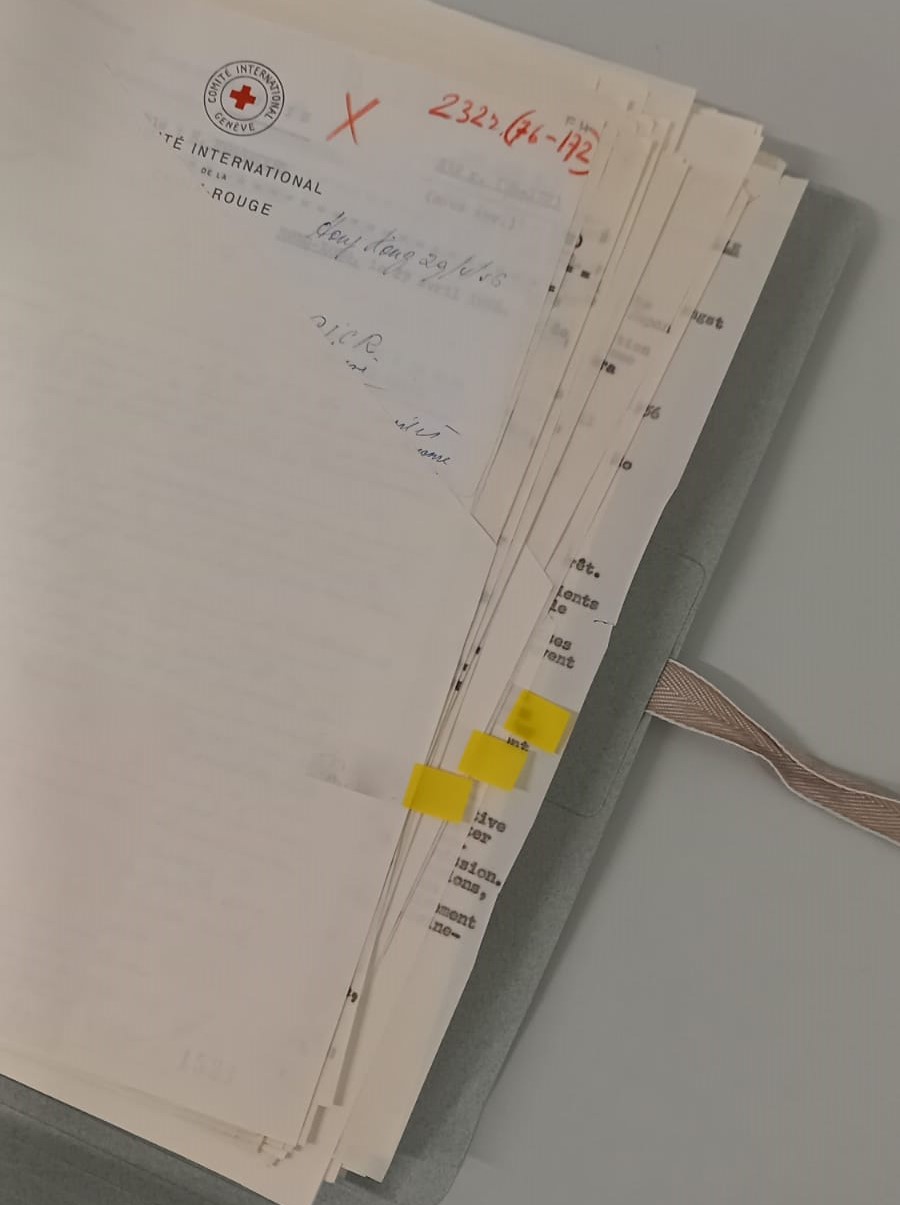

The use of adhesive bookmarks is strictly prohibited in archives: even if they have been stuck onto protective material, they expose the documents to acidic glue and may stain the documents. ACICR

Whether you are in the archives or the heritage library, the rules are the same: food and drink are not allowed in the reading room. Any other items that could stain the documents are also prohibited. This means that felt-tip pens, ink pens, glue sticks and other office supplies are not allowed in the reading room. Readers are asked to have clean, dry hands and to remove any jewellery that could stain or damage the documents they are consulting. Ultimately, only your computer, notebook or pad on which you take notes exclusively with an HB pencil are allowed. Readers are also asked not to lean on or place objects on the documents: for example, your computer cable should be held to the side and not rest on the archives.

Natural light, which is often overlooked, can also cause damage to documents. Ultraviolet radiation contributes to the yellowing of documents: in exhibition halls and museums, lighting is often limited to 50 lux. For old and fragile documents, you may be asked to move to a windowless reading room or to close the blinds to limit the document’s exposure to natural light.

Nothing that could mix up the documents

Readers must also refrain from changing the order in which the documents have been preserved. This is important because many readers sometimes think they are doing the right thing by reorganising sets of documents whose structure they do not understand. However, the order in which a collection is organised is meaningful and allows us to better understand the administrative history of the collection and how it was transferred to the archives. It is therefore important that the order of the documents be preserved for future readers. Changing the order of the documents alters the organisation of the collection and prevents future readers from understanding how the set of documents was used in the past.

This single order may require several days of reading and work in the reading room. The documents have been carefully packaged and prepared by archivists. They must be handled with patience, care and attention to detail.

We therefore recommend that our readers work on each box one at a time, one bundle at a time, one file at a time. As far as possible, avoid starting to “cross-reference your sources” on the spot by opening several files at once, as you risk mixing up the pages in the files and transferring documents to the wrong bundle, thereby losing them.

Meticulousness and patience

Archival documents are fragile and are kept in protective materials: they are made available as is in the reading room. Working with archives therefore requires meticulousness and patience. Reading a document involves removing it from its protective material and returning it to the same material in the exact same place where you found it. The protective packaging must be treated with care and must not be altered or damaged, as this could damage the documents. These small tasks require concentration and cannot be done in a hurry or under pressure. We therefore advise our readers not to overestimate their reading capacity and to avoid requesting too many documents to consult in the time they have allocated themselves. For example, you should avoid ordering several linear metres of documents for a single day in the reading room.

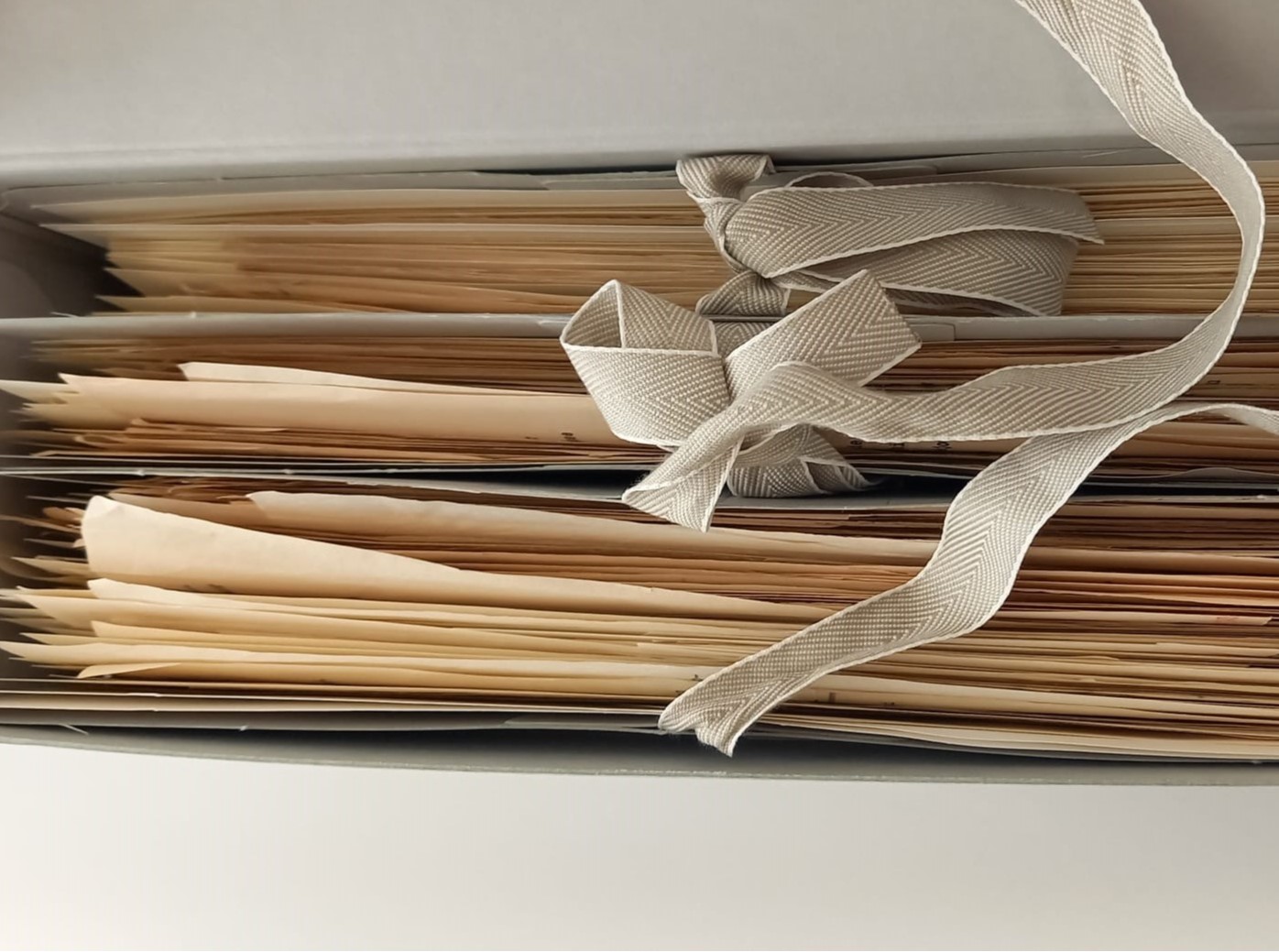

These files have not been put back in a good manner:

Many sheets are sticking out and are at risk of being folded, creased and sometimes even torn.

The ties have not been properly re-tied, which will pose a risk when this file is taken out for the next consultation.

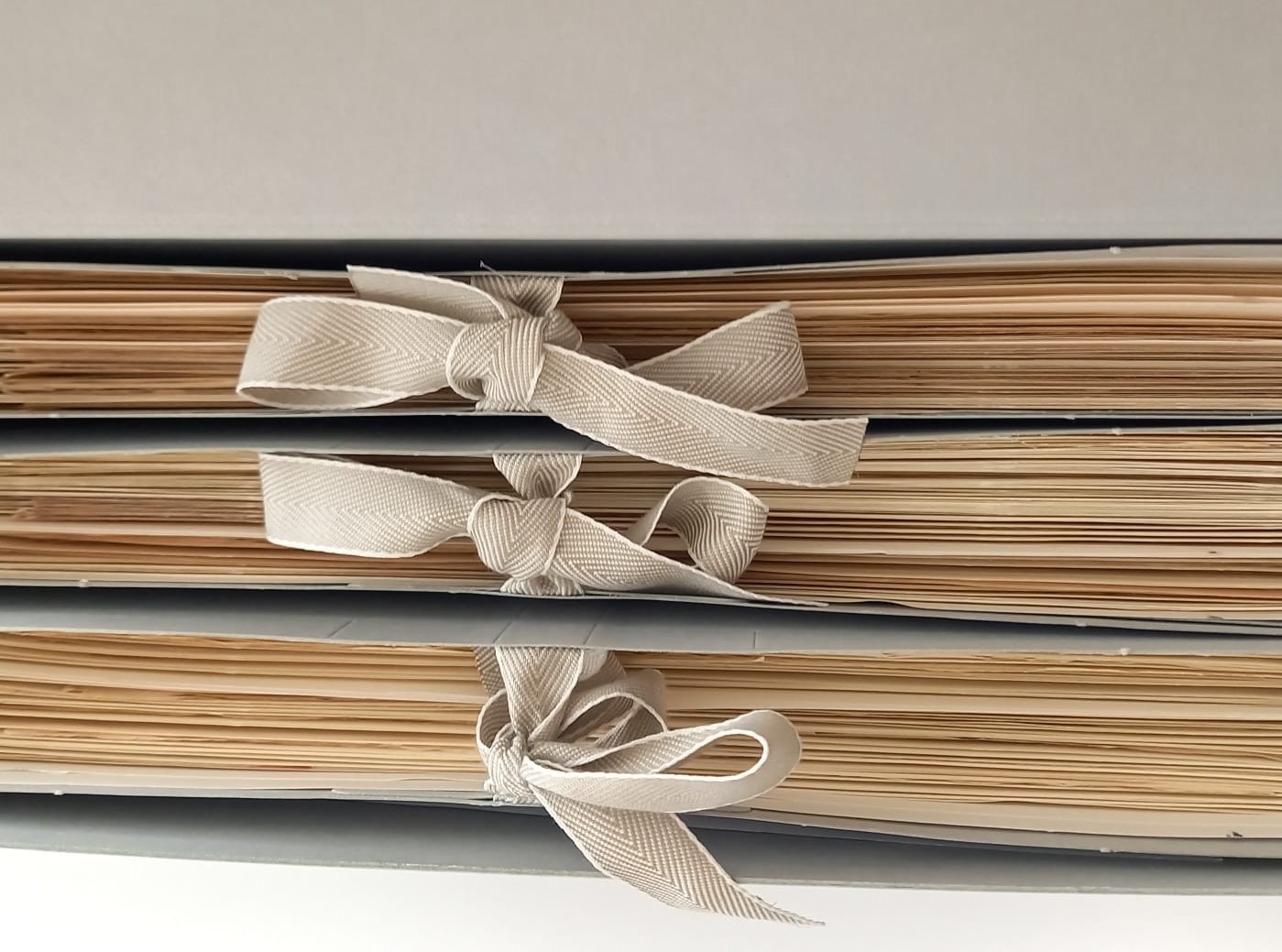

These files are properly stored in their packaging material:

The documents do not protrude from the sleeves.

The three files are thick enough to stand upright.

The file ties are tied loosely so that they can be easily undone.

In general, we ask our readers to keep their work surfaces clean and clear to prevent damage and mixing of documents. When you leave the reading room, documents must be stored in their protective covers and protected from natural light. You can use the bookmarks provided to mark where you left off reading. We also ask that you take care not to inadvertently mix archive documents with your personal notes. You must therefore be prepared to show your notes and notebooks to the archivists on request, so that they can ensure that no documents are taken away inadvertently.

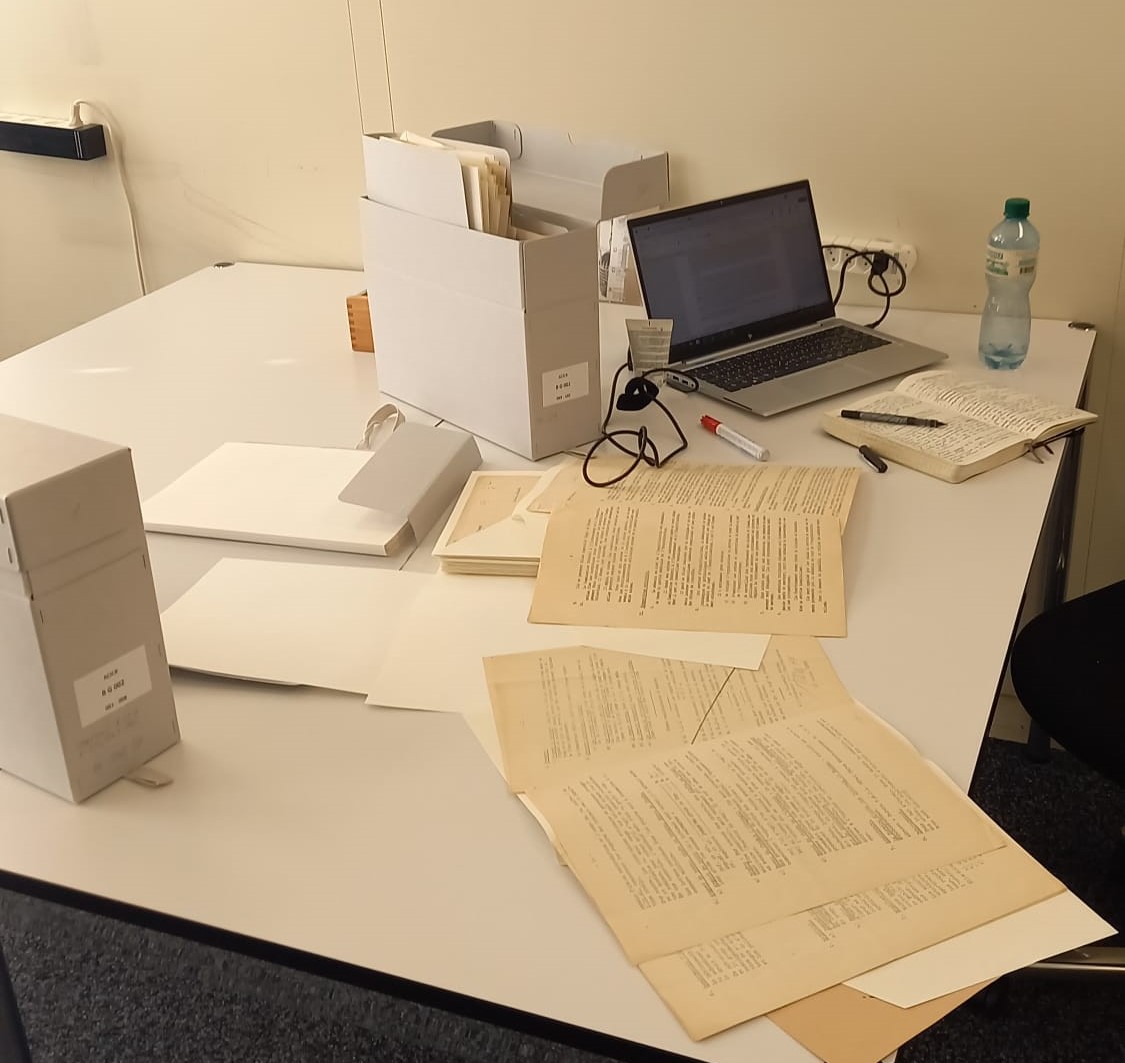

This work plan does not correspond to respectful use of the archives:

The water bottle, felt-tip pens, and tube of hand cream may stain the archives.

The computer cable rubs against the documents and may damage them.

Several different boxes and files are open: there is a significant risk of documents becoming mixed up.

Documents may slip under the covers and flaps of the notebook.

The reader has no space to work and may lean on the documents.

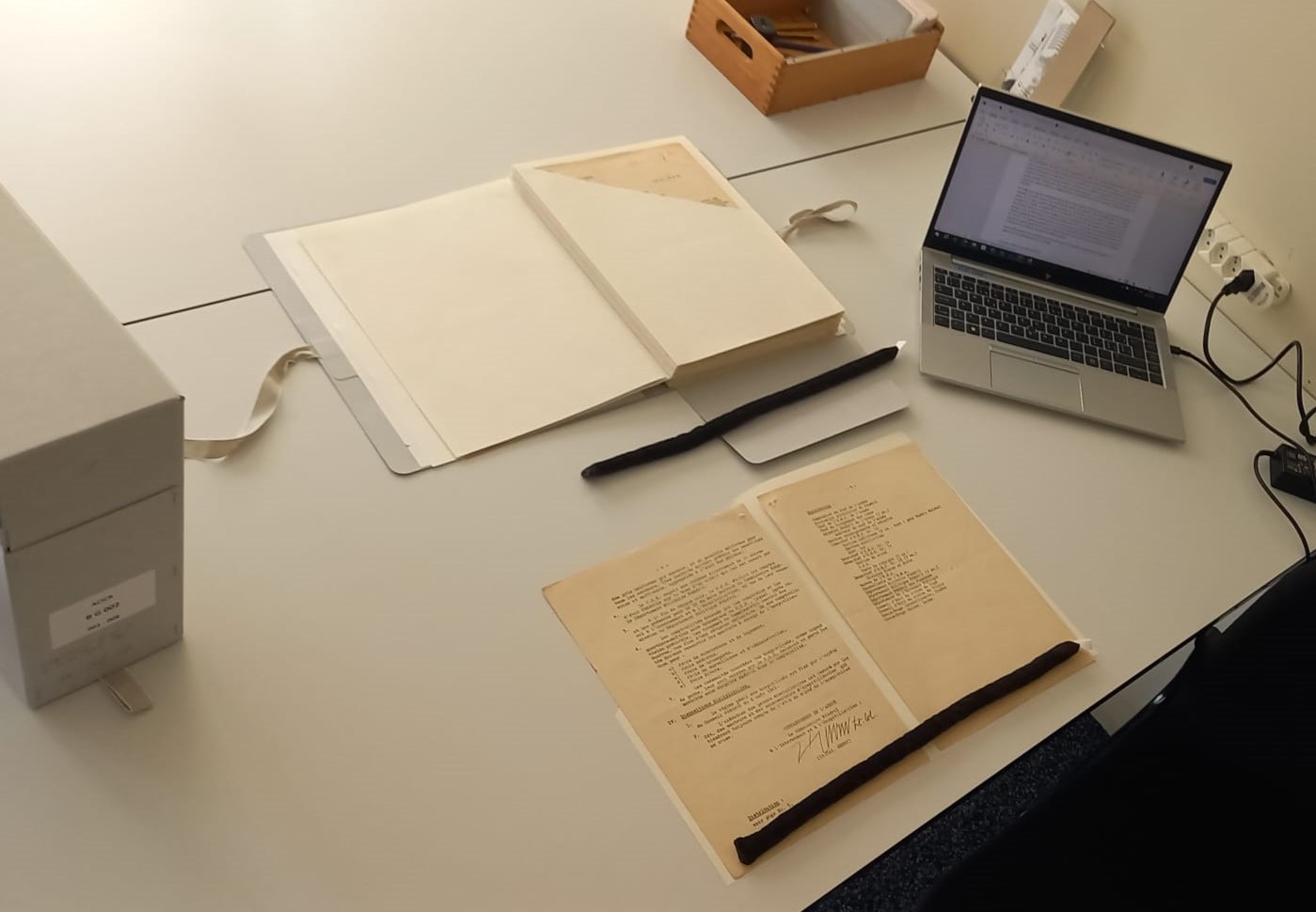

This work plan complies with archive consultation guidelines:

Documents consulted are removed one at a time before being returned to their protective packaging.

Documents not consulted remain in their protective packaging.

The work surface is kept clear and the computer cable does not get in the way.

The reader uses snake weights provided by the archive to keep the documents secure.

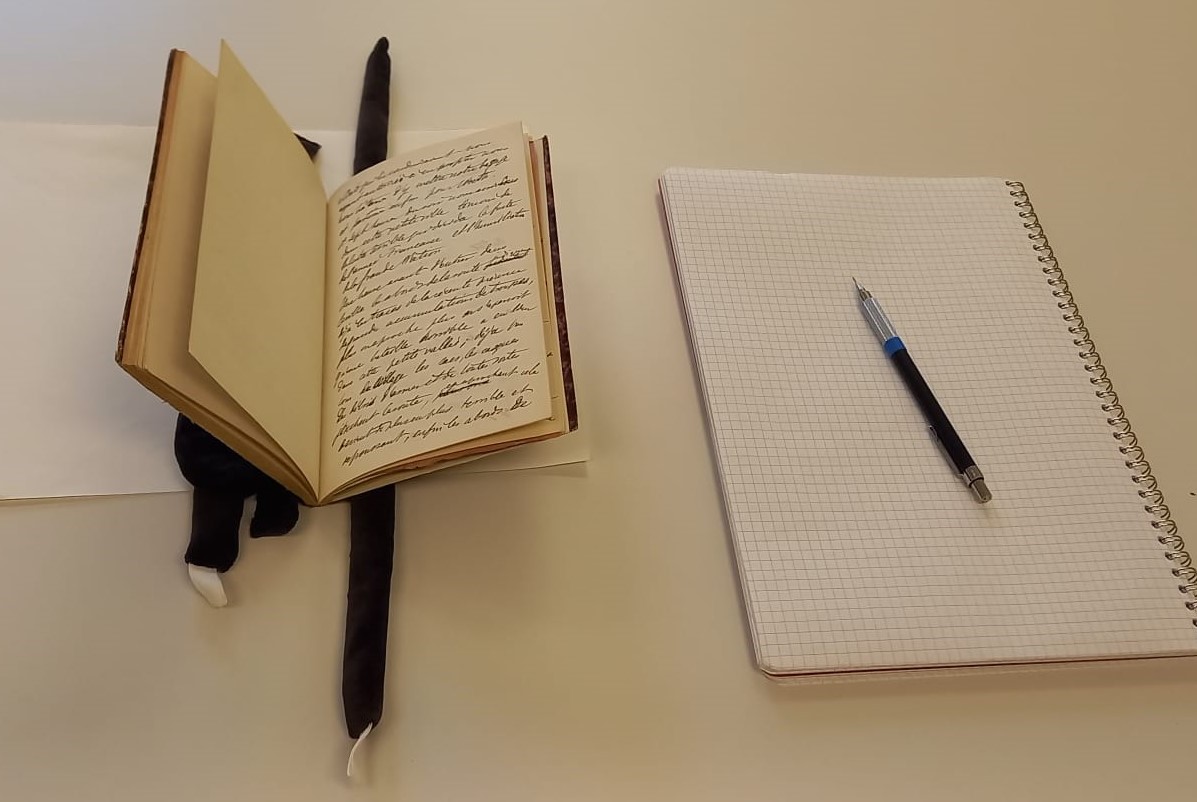

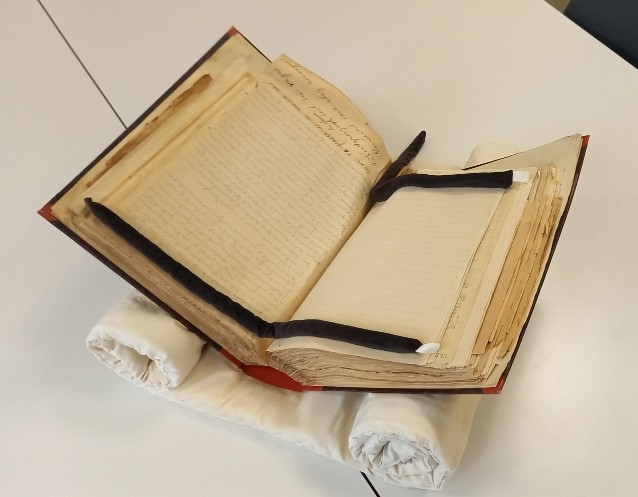

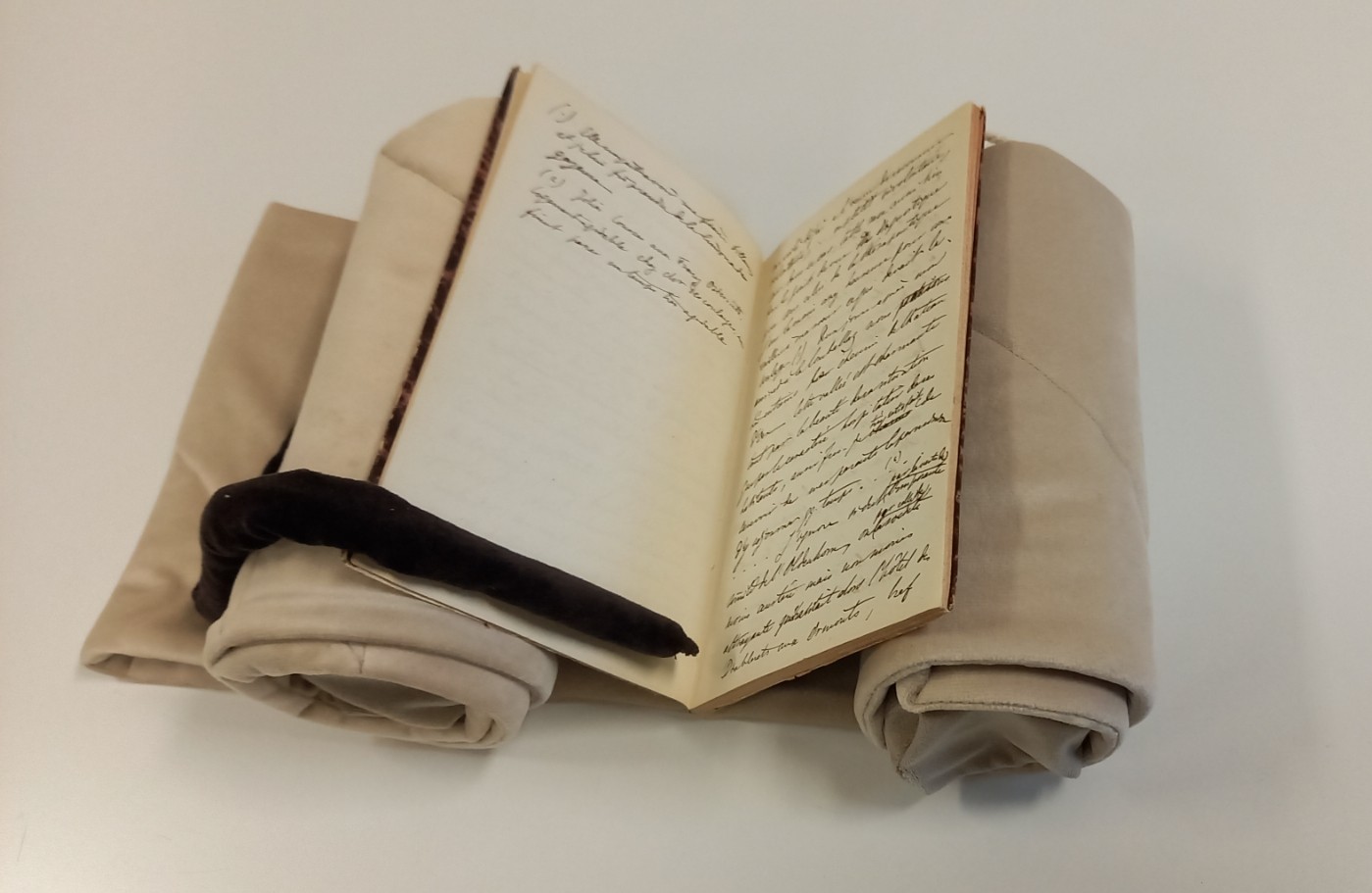

This work plan complies with archival consultation guidelines:

The binding of the volume has not been forced; the reader uses several snakes and a foam support to keep the book open without forcing it.

A sheet of acid-free paper has been placed under the binding to protect it from rubbing against the table.

The window blinds have been closed to protect a 19th-century document from natural light.

Notes are taken with an HB mechanical pencil in a clean notebook.

The reader will present their notes and notebook to the archivist in charge at the end of the consultation to ensure that no pages have been mistakenly slipped into their notes.

Degree of alteration of archival fonds

The ICRC archives keep track of consultations carried out in the reading room. When a reader requests a reference, a loan is recorded in our database. The requested document is temporarily replaced by a “fantôme” (a placeholder) placed on the shelf in the document’s original location. This “fantôme” contains the reader’s first and last names, the date of the loan, and the exact reference of the borrowed document. At the end of the consultation, the documents are returned to their original location and the “fantômes” are retrieved. The archivist in charge can then make a short status report on the documents that have been returned and close the loan. In this way, we keep a history of consultations of loaned documents, which allows us to better document the frequency of consultation of the collections and monitor the condition of frequently requested items.

Some archive centres require their readers to sign registers placed directly at the beginning of each box consulted. These registers take the form of long lists of names where each new reader can see the names of readers who came before them, as well as the number of consultations made before them on the reference requested. This practice is now criticised, particularly in terms of personal data protection. It is not used at the ICRC archives. Nevertheless, this practice highlights an important factor: a frequently consulted collection can pass through several hundred hands. It is therefore very likely that it has undergone alterations. These alterations may sometimes be minimal (for example, if a page has been slightly creased over time), but they may also be more significant (for example, if a letter has been misplaced and is no longer in its original file).

Volume maintained by a futon. ACICR B Mis 67

In archaeology, epigraphy and palaeography, when a text is erased, torn or missing, we say that ‘the document is corrupted’. By analogy, we could therefore reuse this expression to refer to archive collections in which losses and damage have been observed. The number of times a document has been consulted is an important ‘corruption index’ that researchers must keep in mind when carrying out their work and considering their methodology. Working on an archive collection that has been available for consultation for 30 years and is widely cited is quite different from working with an unexplored archive collection.

While not all research topics lend themselves to the discovery of unexplored collections, all readers must nevertheless commit to working with the same care and rigour when in the reading room. We count on your careful and rigorous cooperation to preserve the richness of the ICRC archives!

Comments