Between December 1935 and spring 1936, approximately 20 Red Cross and Red Crescent field hospitals entitled to protection under the Geneva Conventions were attacked by the air force of fascist Italy. The role of the hospitals was to care for sick and wounded personnel of the Ethiopian army. These incidents are relatively unknown today, but the ICRC has preserved valuable photographs that bear witness to these events.

Introduction

The ICRC and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in Ethiopia

On 3 October 1935, after months of political and diplomatic tension, Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship attacked Ethiopia with the aim of absorbing it into the Italian colonial system, triggering the Second Italo–Ethiopian War[1]. In Geneva, the ICRC moved quickly. The following day, the organization contacted the Ethiopian Red Cross Society (hurriedly created a few months previously) [2] and the Italian Red Cross, which was under fascist control [3], suggesting an appeal to the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement asking the National Societies to offer their assistance. The Italian Red Cross declined, as it had sufficient supplies and personnel, but the Ethiopian Red Cross Society (which the Emperor had ordered to provide medical services for his army) accepted immediately, hoping to compensate for its lack of resources. Twenty-three Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies responded to the appeal issued by the newly created Ethiopian Red Cross Society and provided aid in various forms as part of an international humanitarian operation [4].

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Macalle. Italian Red Cross hospital. V‑P‑HIST‑02491‑12A.

The Italo–Ethiopian War was a milestone in the history of the ICRC [5], and marked the beginning of the modern era as regards the organization’s humanitarian operations. This conflict was the first time that the ICRC had engaged in what we now call “humanitarian diplomacy” [6], worked directly with National Societies in the field [7] or deployed delegates right from the outbreak of a conflict [8].

© ICRC, Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935‑1936. Ethiopian Red Cross truck. V‑P‑HIST‑02754‑03A.

On 6 November 1935, one month after the outbreak of hostilities, Sydney Brown (a lawyer) and Marcel Junod (a doctor, who had just joined the ICRC) arrived at Addis Ababa airport as ICRC delegates. Their main task was to act as neutral contacts who would enjoy the confidence of the various National Societies operating in Ethiopia. They were also to support the seven field hospitals deployed by the Ethiopian Red Cross Society and the eight field hospitals sent by six neutral National Societies [9], bringing to 15 the number of mobile hospitals on the Ethiopian side that were displaying the red cross or red crescent emblem. As we will see, those emblems did not protect them against the bombs of Mussolini’s air force.

© ICRC, Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935‑1936. Sydney H. Brown and Marcel Junod with doctors and first-aiders of the Ethiopian Red Cross. V‑P‑HIST‑00977‑27.

Was the Red Cross targeted by fascist aircraft?

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935‑1936. After the destruction of the British field hospital by the Italian Air Force. V‑P‑HIST‑02754‑35A.

“It has become clear that there is scarcely a single Ethiopian or foreign field hospital that the Italians have not destroyed or attempted to destroy.” Sydney Brown [10].

While less well-known and documented than the large-scale use of mustard gas, air strikes on hospitals, field hospitals and medical aircraft displaying the red cross or red crescent were nonetheless among the most important IHL violations of this war, not only on account of their number (between 17 and 23, depending on the historical study or Ethiopian government source one consults [11]) but also in terms of the deaths, trauma and damage they caused. Furthermore, the fact that these attacks were carried out repeatedly and that the majority of Red Cross and Red Crescent field hospitals operating on the Ethiopian side were directly or indirectly damaged by Italian Air Force bombing means that then as now one is forced to ask whether the attacks were deliberate or not.

Both parties to the conflict had ratified three fundamental treaties concerning the law of war. These were the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare (1925), Hague Declaration IV,3 concerning Expanding Bullets (1899) and the Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field (1929) – of which one of the objectives was to protect “fixed establishments of the medical service”, “mobile medical formations”, their means of transport and their medical personnel. When Haile Selassie ratified these three treaties in 1935, it was in expectation of imminent conflict. However, he refused to sign the 1929 Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, which Italy had ratified in 1931.

In attempting to answer this question, it is useful to look briefly at certain aspects of Mussolini’s philosophy, which saw as legitimate the elimination of anything not in the interests of fascist Italy [[12]. So when the question of air-raids on Red Cross facilities was raised in 1935 during discussions between him and Georges Wagner, the Swiss ambassador to Italy, Mussolini described the humanitarian field hospitals as “nuisances”, and went on: We shall give them [the Ethiopians] hospitals … along with roads, schools, doctors and all the advantages of civilization [13]. Quite apart from the concept of the “civilizing mission” advanced by Mussolini to justify these flagrant breaches of IHL, there was also the colonial attitude common in Italy and elsewhere in the West – and at the ICRC – that because of what was claimed to be its lower level of civilization, Ethiopia was not capable of adopting the standards of the Geneva Conventions, nor of understanding the principles that underpinned the work of the Red Cross. Drawing on this colonial mindset, the fascist regime constantly accused Ethiopia of violating the Geneva Conventions, generally without proof, in an effort to justify reprisals that were themselves completely contrary to those Conventions [14]. Italy’s list of accusations was headed by abuse of the red cross emblem for military purposes, either to protect soldiers and weapons or to hide their positions. In a letter to the ICRC, Italian Red Cross president Filippo Cremonesi wrote: Far from understanding the primordial significance and correct usage [of the red cross], the Abyssinian warriors have come to believe that it holds miraculous powers … On many occasions, as our official communiqués have confirmed and as photographic evidence amply demonstrates, they use very large red crosses in the field, clustering about them to protect themselves against the attacks of our aircraft. While one might understand such abuses perpetrated by barbaric, primitive warriors, they become unjustifiable when the Abyssinian authorities themselves regularly resort to such practices in order to conceal ammunition depots and military establishments [15]. These accusations of perfidy, which fascist propaganda published widely and to which the ICRC gave serious credence, without its delegates ever being able to confirm them [16] gave the Italian side a pretext for bombing facilities, personnel and patients protected by the Conventions and identified by means of the distinctive emblem.

Haile Selassie’s government protested repeatedly against these attacks, both to the League of Nations and to the ICRC. However, the ICRC – concerned about preserving its neutrality and afraid of angering the Italian government – refrained from denouncing them. Sydney Brown was quicker than his colleagues in Geneva to see these bombings as clear, inexcusable breaches of the Conventions, and was certain that the Italians are targeting the Red Cross Societies with their bombs wherever they find them [17]. Dr Junod’s interpretation and position were more ambiguous. At the outbreak of hostilities, the famous delegate considered it highly plausible that some of these attacks were malicious. However, during the final months of the conflict and the years that followed (during which he developed anti–Ethiopian views inspired by a certain measure of racism) he took the much more pro-Italian view that the bombings were unintentional. Finally, at the end of the Second World War – when fascism was encountering international condemnation – Junod returned to his original position [18]. This is apparent from his famous work Warrior without Weapons (1947), in which he does not hesitate to emphasize the absence of humanitarian consideration displayed by the fascist army.

What the ICRC audiovisual library tells us about the bombing of the Red Cross in Ethiopia

Having set the scene a little, let us now turn to the evidence in the ICRC audiovisual library. 171 of the library’s photographs cover the Italo–Ethiopian War, and about 30 of those show Red Cross field hospitals immediately after attacks by the Italian Air Force. Those photos show the damage suffered by the Swedish and British Red Cross field hospitals. There is also a photo of Haile Selassie visiting the location of one of the Ethiopian Red Cross field hospitals, which had suffered major damage during the bombing of Dessie. This means that of the 20 or so direct or indirect air strikes on Red Cross or Red Crescent facilities that are known to have occurred, only three are documented in the ICRC audiovisual library. But while the limited nature of this collection makes it impossible to fully comprehend the scale of the phenomenon, or the fact that virtually all Red Cross and Red Crescent field hospitals on the Ethiopian side were affected, the impact of the available photos makes the seriousness and significance of these attacks abundantly clear.

Not until the Second World War did the ICRC really step up its use of photography as documentary evidence [19], but the reports submitted by Junod and Brown are a sign of things to come. On a number of occasions, the two delegates attached photos to the reports and letters they sent to their colleagues in Geneva, some of which supplemented and reinforced those documents or the information they received regarding air attacks. However, with two exceptions, these photos were separated from their associated reports [20] and some have disappeared. Furthermore, as in the case of most photos in the ICRC audiovisual library taken before 1950 [21], most of those covering the Italo–Ethiopian War are anonymous, prompting a number of questions (often unanswerable) regarding the aims and motives of those who took them, and their origins. ICRC delegates were by no means the only photographers providing images for the rich collection that the ICRC holds; many came from National Societies, private individuals, journalists, governments and other sources.

The bombing of Dessie – and the Red Cross

On 6 December 1935, Italian bombs rained down on the town of Dessie and its citizens. The principal aim was to kill the emperor, who was intending to lead the defence of his country from the northern town. During the hour–long attack, five bombs hit Tafari Makonnen Hospital, causing serious damage but miraculously leaving only one person injured. The three Ethiopian Red Cross field hospitals stationed at Dessie when the raid occurred did not escape. Field Hospital No. 2, which had been set up in the park surrounding the buildings of the permanent hospital, lost its operating tent, which was completely destroyed by a sixth bomb. Bombs also exploded ten metres from Field Hospital No. 3, sited on a hill near the town. Several Red Cross doctors stated in a telegram to the ICRC [22] that all these facilities were clearly identified by the distinctive emblem. Dr Junod, who was sent to Dessie on a reconnaissance mission a few days later, confirmed their statements in his report to Geneva dated 17 December. He also mentioned having noted the presence of a large red cross measuring approximately eight metres by eight metres on the roof of Tafari Makonnen Hospital. He adds: I have taken photographs of this, and of two holes made by the incendiary bombs. Junod intended these photos to serve as visual evidence of an incident that he described in his report as a flagrant breach of the Geneva Conventions [23]. But what happened to this photographic evidence? Our research has uncovered neither the photographs nor an answer to this question.

As we mentioned above, there is only one photo linked to this event in the ICRC audiovisual library. This is a picture taken by an unknown photographer, showing Haile Selassie, accompanied by his son (on the right of the photo), doctors and various dignitaries, visiting one of the three Ethiopian Red Cross Society field hospitals following the attack. It is not clear which of the three hospitals appears in the photograph. The image does not show the damage caused by the bombs; it is only the caption that links the photo with the incident.

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Dessie. Haile Selassie, accompanied by his son, visits an Ethiopian Red Cross Society field hospital following the air raid. V P‑HIST‑02751‑28A.

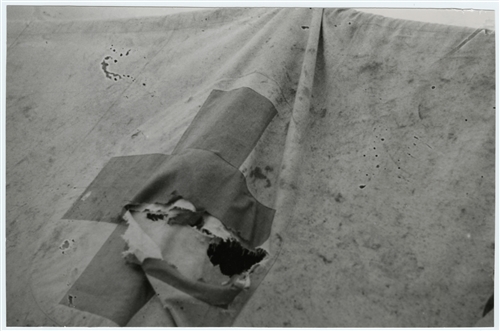

Two months later, on 9 February 1936, an air strike targeted Dessie airport, where the Ethiopian Red Cross Fokker piloted by Carl Gustaf von Rosen was standing. Junod reported that the aircraft had been subjected to merciless bombing by the Italian Air Force, and escaped only by a miracle [24]. There are two photographs of this incident in the ICRC’s “paper” archives (as opposed to its audiovisual library). Unusually, they have not been separated from the document they originally accompanied – in this instance a report from Brown to ICRC HQ dated 21 February 1936. They show multiple shrapnel holes in the tail and one of the wings.

ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 10 by Sydney Brown to ICRC headquarters, 21 February 1936, annexe.

Belaten Gueta Herouy, president of the Ethiopian Red Cross Society, described this as further proof of the determination of the Italian Air Force to attack any object bearing the red cross [25]. Indeed, between the Dessie attack of 6 December 1935 and the attack on 9 February 1936, no fewer than 12 air raids of varying intensities imperilled the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies operating on the Ethiopian side to a greater or lesser degree, leaving little respite for their patients and staff. The most serious of these attacks was that perpetrated on the Swedish Red Cross field hospital, of which the ICRC has more visual evidence.

“Reprisals” against the Swedish Red Cross

© ICRC, Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Melka Dida. The Swedish field ambulance before the air raid of 30 December 1935. V‑P‑HIST‑02751‑22A.

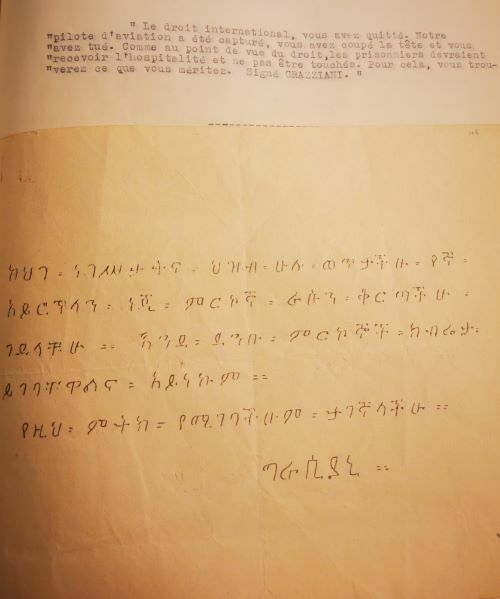

So let us head for the southern front, in the tracks of the Swedish Red Cross field hospital, which was subjected to a particularly heavy air raid on 30 December 1935 at Melka Dida (near Dolo) while it was caring for the sick and wounded soldiers of Ras Desta’s forces. This raid formed part of the reprisals conducted by General Graziani in revenge for the killing of an Italian pilot in the Ogaden. The Egyptian Red Crescent field hospital and Ethiopian Red Cross Field Hospital No. 1 also fell victim to these reprisals, in Bulale on 30 and 31 December 1935 and in Degeh Bur on 4 January 1936 [26]. The only pictures from this grim series to have reached us are those showing the results of the attack on the Swedish field hospital. At 07.30 hrs, a dozen Italian aircraft attacked the field hospital after dropping leaflets in Amharic, of which the content confirmed the intentional nature of the attack. The ICRC archives hold a copy of the leaflet, along with a literal French translation, of which the (equally literal) English translation reads: International humanitarian law, you have left it. Our aeroplane pilot has been captured, you have cut the head and you have killed. As from the point of view of the law, prisoners should receive hospitality and not be touched. For that, you will find what you deserve. Signed GRAZIANI. Over a period of some 20 minutes, no less then 3,134 kg of explosives were dropped on the hospital, including 252 kg of mustard gas [27]. The attack left 42 staff and patients dead and approximately 50 wounded.

One of the leaflets dropped by the Italian Air Force, which Marcel Junod sent to ICRC headquarters. ACICR B CR 210 15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 2 from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 13 January 1936, annexe.

The attacks left the Ethiopians and Red Cross/Red Crescent personnel in the field – including the ICRC delegates – stunned and incredulous. Brown, almost believing the affair had been a bad dream, wrote to his colleagues in Geneva on 3 January 1936: Junod and I found this bombing affair so utterly inexplicable that we decided one of us absolutely had to visit the scene as quickly as possible to draw up an official report [28]. Which is what happened. The following day, Junod boarded the Ethiopian Red Cross Fokker piloted by von Rosen and visited the field hospital, which was patching itself up in Negele where it had taken refuge. He travelled to the scene of the incident the day after and reported: Of all the areas at the front which I have been able to observe with my own eyes, none has been bombed with such intensity as the camp of the Swedish field hospital [29].

Junod brought back photos from Negele and Melka Dida, which he attached to his report to Geneva [30], along with a list of captions that he sent with a letter a few days later [31]. As these photos were later separated from their reports, many of them are now missing. Others, however, appear to be in the ICRC audiovisual library. While the library database now shows the photographer as unknown, it is probable that they were taken by Junod. That is in any case a reasonable hypothesis, based on a comparison between the photographs and the lists of captions. Six photos show personnel of the field hospital treating patients in Negele, just after the attack. Another shows the grave of nurse Gunnar Lundström, the only Swede to die in the attack – and the only person to have been given a burial ceremony and a marked grave, the Ethiopian victims having been hastily buried in bomb craters. One photograph shows a field hospital truck parked under cover of vegetation to hide it from the Italian Air Force.

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Negele. Following the Italian Air Force attack on the Swedish field hospital. V‑P‑HIST‑03504‑02A.

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Negele. Grave of Gunnar Lundström. V‑P‑HIST‑02752‑02A.

The ICRC audiovisual library also holds a film of the damage to the Swedish field ambulance, containing footage shot by US journalist Howard Winner. Winner accompanied Junod on his reconnaissance mission to Negele and Melka Dida. He was one of the few reporters whom the Ethiopian government authorized to visit the front (with a view to convincing public opinion and the international community of the reality and seriousness of the air raid). It is worth mentioning the striking similarity between the photographs mentioned previously and some of the shots in Winner’s footage. It could well be that it was he rather than Junod who took the photographs, but the question remains open.

Two further photographs complete the series taken during the mission to Negele and Melka Dida. These show the bodies of people killed during an air raid that targeted Negele directly and was carried out in parallel with that on Melka Dida. In this instance, we know that the photographer was Carl Gustaf von Rosen.

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Negele. A victim of the Italian air raid. V‑P‑HIST‑02753‑02A.

Given the scale of the incident, and the indignation of the Ethiopian and Swedish governments – who were demanding an independent inquiry – it became essential that the ICRC speak to the Italian authorities. On 7 January 1936, ICRC president Max Huber sent a very cautious letter to Mussolini [32]. Huber’s letter asked for guarantees concerning compliance with the Geneva Conventions and respect for medical facilities identified by the red cross or crescent. The dictator replied, inter alia that his army and his government were prepared to cooperate in order to allow the principles established by the norms and conscience of civilized people to triumph, but that the possibility of such “accidents” could never be totally excluded in time of war [33]. The ICRC’s diplomatic approaches clearly had no effect, as a further 13 similar attacks took place. The most severe of these include the air raid on Ethiopian Red Cross Field Hospital No. 3 at Amba Aradam on 18 January 1936 [34] (of which there are no photographs in the ICRC audiovisual library) and, above all, that on the British Red Cross field hospital in the Korem Plain on 4 March.

A double air raid based on suspicion: the destruction of the British Red Cross field hospital

ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935‑1936. British Red Cross Society field hospital. V‑P‑HIST‑03086‑16.

In March 1936, the Italian victory was near. The fascist army was mopping up the last pockets of resistance offered by such of the Ethiopian forces as were still fighting. These included troops under the command of Ras Moulougueta and Ras Kassa in Tigray, for which the British Red Cross field hospital had been tasked to provide medical services. Despite the attacks that several of its “sister ambulances” had suffered, the staff of the British ambulance had confidence in the two large red cross flags (measuring 10 m x 10 m and 14 m x 14 m) that it laid out on the ground immediately after arriving in the Korem Plain on 2 March 1936. They could not have imagined that the Italian Air Force – which had been observing them since 29 February – suspected them of hiding Ethiopian soldiers and weapons. Those suspicions turned to certainties in the mind of one Italian Air Force pilot, Guido Vedovato. On 4 March 1936, having decided that one of the Red Cross trucks was carrying weapons, and having seen suspicious movements, he opened fire and dropped a first 24 kg of bombs on the hospital. Another 774 kg of explosives followed, bringing death and destruction to the hospital later that day. Five patients died immediately and others were injured. There were no casualties among the staff of the hospital. The damage was extensive. 35 tents were destroyed, along with some of the medical supplies, two trucks and the larger of the two flags, measuring 14 m x 14 m, on which the hospital had relied for visibility and hence protection. Leaving behind the supplies and equipment that had been destroyed, and hurriedly burying four of the victims in bomb craters, the badly-damaged hospital broke camp that same day and went in search of a place to hide. That decision turned out to be their salvation. The following day, as part of the air raid on the town of Korem, the Italian Air Force came back to bomb the hospital (or what was left of it) for a second time, unaware that everyone had left [35].

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Korem Plain. Following the destruction of the British field hospital by the Italian Air Force. V‑P‑HIST‑02754‑02A.

Junod gave the Italians the benefit of the doubt as to whether the bombing of the hospital had been deliberate or accidental [36], but Brown saw this as yet another deliberate breach of the Conventions, and one that required that the ICRC react more strongly, devote more attention to the matter and obtain real guarantees from Mussolini’s government. On 12 March 1936, in his report to his colleagues in Geneva, Brown wrote: We would just have liked the ICRC to obtain information as to whether the Italian government had decided to destroy all neutral field hospitals, even if they were very clearly displaying the emblem of the Red Cross, so that if that were to be the case, we might inform the neutral Red Cross units, for which we have assumed a certain degree of responsibility [37]. Some two weeks later, Brown wrote directly to Étienne Clouzot, the head of the ICRC secretariat, adding 25 photos to his report. However, neither he nor Junod took those photos – they did not conduct enquiries at the scene. The photographer was a journalist by the name of Zeitlin, whom Brown described as a “Russian Bolshevik”. Zeitlin had fallen ill, and was being cared for by the personnel of the field hospital at the time of the incident. This meant that just a few minutes after the attack, he was able to take a number of photographs that he later passed on to Brown, who kept copies of them in case the Italians tried to go through the mail [38]. We have been able to find 21 of the 25 photos that Brown sent to Clouzot. All have been separated from the letter they originally accompanied, but fortunately it is easy to match them up thanks to the information and list of captions that Brown provided.

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Korem Plain. Following the destruction of the British field hospital by the Italian Air Force. V–P–HIST–02754–11A, V–P–HIST–03503–28A, V‑P‑HIST‑02754‑13A, V‑P‑HIST‑02751‑04A.

The violence it portrays makes this series of photos truly striking. It constitutes a permanent record of the incident – the deaths, injuries and damage it caused – and forms a poignant reportage, documenting the loss of life (three photos), injuries to patients – including some caused by mustard gas (three photos), the destruction of supplies and equipment (14 photos) and the means used to destroy the hospital (one photo). Here, photography plays its role of providing documentary evidence that could be used to support denunciation of breaches of the Conventions. That, at least, was Brown’s intention when he sent the pictures to Clouzot, two weeks after having fiercely denounced the air raid – and the fascist army in general – to his colleagues in Geneva. That was no doubt Zeitlin’s intention as well. According to Brown, he had not only taken photos but also made a film (which we have been unable to trace) that was to be shown in Paris, London, etc. as propaganda [39].

Realizing that Mussolini’s “pious hopes” had not ended the bombing of Red Cross and Red Crescent field hospitals, Max Huber and his colleagues of the Committee decided to send a delegation to Rome, to discuss the matter with the Italian government. The delegation arrived in Rome on 24 March 1936, three weeks after the attack on the British field hospital. In between sightseeing trips and high-society dinners, they listened patiently to the explanations of Filippo Cremonesi and the fascist authorities, who continued to propound the theory that the incidents were accidents related to the difficulty of identifying the Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems from the air. However, in the case of the British field hospital (and others) the Italian Air Force had clearly identified the emblem several days before the attack [40]. After reminding the Italian authorities of their duty never to carry out reprisals against the Red Cross or the Red Crescent, under any circumstances, the ICRC delegation returned to Geneva, satisfied with its meeting – and without having examined the inconsistencies between the testimonies of the victims, its own delegates and the Ethiopians on the one hand, and the responses provided by the fascist government on the other [41]. Be that as it may, these approaches came too late, and the Red Cross and Red Crescent units had to protect themselves by means that did not involve going via official or diplomatic channels.

Should we hide the emblem or make it more visible?

As we have seen, the direct attacks on the Swedish and British field hospitals meant they had to conceal themselves in order to continue operating. Both decided to use trees and vegetation to camouflage the hospitals and the emblems, as they felt – rightly or wrongly – that their red crosses would make them targets for the Italian Air Force rather than protect them. The British field hospital moved into a cave suggested by Haile Selassie. A cave also protected Ethiopian Red Cross Field Hospital No. 3 during a heavy air raid on 18 January 1936 [42].

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936. Negele. Red Cross trucks and emblems camouflaged following the air raid. V‑P‑HIST‑03504‑03A.

Disillusion regarding the emblem inevitably spread among the Red Cross and Red Crescent units, despite the words of Max Huber that appeared in the Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix–Rouge following receipt of Mussolini’s reply mentioned above: These assurances [provided by Mussolini in his reply] allow us to conclude that if an Ethiopian or foreign field hospital were to suffer aerial or other attack, this would be purely the result of a conjunction of exceptional circumstances outside the control of the Italian government … The telegrams that the International Committee of the Red Cross has sent to its mission in Ethiopia have been interpreted in this sense. The heads of the Ethiopian and foreign field hospitals, who had been inclined to abandon the use of all distinctive signs, have decided, conscious of the high standing of the assurances we have received, to fly the Red Cross flag with confidence [43]. In practice, however, very few Red Cross or Red Crescent field hospitals decided to fly the Red Cross flag with confidence, any more than they were conscious of the high standing of the assurances provided by Mussolini [44]. Confidence had long since been replaced by doubt. How were they to protect themselves under such circumstances? What was to be done with an emblem that was supposed to protect, when it appeared to attract danger? Was the emblem really not visible from the air, or were these deliberate attacks on the part of the Italian Air Force? These questions continued to be debated throughout the war, leading on occasion to heated discussions as to whether one should make the “flag of humanity” more visible or hide it away altogether. Fearing that if the emblem were to be abandoned in this conflict it would be abandoned everywhere and forever, the ICRC delegates initially insisted that the field hospitals continue to display it, while ensuring that it was even more visible [45]. In this they were only partly successful. In his report of 20 February 1936 regarding Ethiopian Red Cross Field Hospital No. 2 and its chief medical officer Dr Dassios, Junod wrote: As soon as an aircraft is reported … Dassios … takes down his tents and flags and moves his immobile patients to a safe location. All those capable of moving take cover in holes! [46] Later in his report, Junod tells his colleagues in Geneva that he wants to resolve the question of the visibility of Red Cross flags from the air by means of tests using the Ethiopian Red Cross Fokker, which he conducted during the following weeks [47]. In his next report, dated 12 March 1936, Junod announced that tests had been conducted with three different red cross emblems: a 9 m x 9 m flag spread out on the ground, a 60 cm x 60 cm emblem painted on a lorry and a 1 m x 1 m emblem on the wing of an aeroplane. His conclusions were as follows: the 9 m x 9 m flag was clearly visible, even from an altitude of 2200 m. The 60 cm x 60 cm emblem disappeared at 200 m and the 1 m x 1 m emblem at between 400 m and 500 m [48]. Three photos from these tests have been preserved. They were taken by the pilot, von Rosen, at altitudes of 2000 m to 2200 m. As reported, one can clearly see the Red Cross flag on the ground, whereas the emblem on the aeroplane is invisible.

© ICRC Archives (ARR), Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936, Aerial view of a field hospital (taken from 2000 m–2200 m). V‑P‑HIST‑02753‑28A.

Barely five days after submitting the results of these tests, Junod and von Rosen faced the “camouflage/visibility” dilemma themselves, on a trip to deliver medical supplies to field hospitals on the northern front and to take Dr Van Schleven of the Dutch Red Cross back to Addis Ababa, as he had been injured in an attack by bandits. After landing on Korem Plain, they decided to camouflage their aircraft on the morning of 17 March 1936 for the simple reason, according to Junod, that it had been bombed twice in Dessie, despite the emblems [49]. Shortly after leaving the place where they had landed, they saw that the Italian Air Force was attacking Haile Selassie’s aircraft, which was standing next to the Ethiopian Red Cross Fokker. Aware of the danger facing the medical aircraft, they returned as quickly as they could to remove the camouflage, in the hope that the Italians would see the emblems and refrain from attacking it. Their efforts were in vain. The Fokker was attacked three times. One of the attacks was carried out from an altitude of 30 m, from which the emblem was clearly visible, as indicated above. The Fokker was completely destroyed. Mustard gas was dropped all around, turning the plain into an absolute hell. Innumerable civilians and soldiers were killed or wounded, a situation made even worse by the last air raid on the English field hospital [50].

So by March 1936, any remaining illusions had evaporated. One of Junod’s reports illustrates this: Following the air raids on various units and hospitals, the prestige of the red cross emblem has fallen to zero – or less than zero, because people are avoiding it. On the northern front you will not find a single Red Cross flag, except at the Dutch unit in Dessie. Everyone is hiding as best they can. This is indeed perfectly logical, and we should have thought of camouflaging our front-line field hospitals earlier [51]. Brown did not hide his indignation from his colleagues at headquarters, to whom he had sent photos of the Fokker so that the ICRC could send them to the Italian Red Cross, which should then send them to the Italian army and government, so they could recognize the Fokker and identify it as protected by the Geneva Conventions. As far as he was concerned, therefore, the Italian pilots must have known exactly what they were doing when they destroyed it. He went on: I am actually rather annoyed at myself for having sent you all these photos, which may even have made it easier for our Italian friends to find our aircraft [52]. According to Brown, sending the photos – which was supposed to ensure protection – might in fact have had the opposite effect.

Conclusion

It is worth asking whether the images of bombed Red Cross hospitals played any role when the ICRC should have been drawing up an impartial assessment of compliance with the Geneva Conventions as regards the abuse of the Red Cross emblem (reported by Italy) on the one hand and the attacks on Red Cross units, especially in the form of air raids (reported by the Ethiopians) on the other [53]. Two months after the war ended, Max Huber asked Marcel Junod [54] to produce a report based on the documentation that the ICRC has been able to collect regarding the Italo–Ethiopian conflict [55] to clarify these two questions. On the first point, the report concludes that while he had not personally observed any intentional abuse of the Red Cross emblem during his travels on the Ethiopian side (except for a few minor details of minimal importance), Dr Junod stated that as far as ordinary Abyssinians were concerned, it was primarily a matter of ignorance regarding the value of the emblem [56]. Regarding the conclusions concerning the air raids on Red Cross units, we should point out that by allowing Italy to comment on his observations and conclusions prior to publication of his report, Junod did show a degree of indulgence towards them in the final version [57], despite the documentation in the ICRC’s possession, which regularly highlighted violations of the Conventions by the fascist armed forces. The images, written documents (reports, testimonies, telegrams, letters) do not make it possible to clearly establish their responsibility, and the ICRC’s final report of December 1936 gave the Italians the benefit of the doubt in all cases [58].

Finally, we should point out the documentary and historical value today of the photographs that this article has presented and analysed. While the Italo–Ethiopian War attracted widespread media attention in the West [59], most of the photos were taken very much on the fringes of the conflict, by journalists who were in the country but had generally not been authorized to go near the front. This led to the taking (and widespread publication) of “background” and “exotic scenery” pictures [60], which do not even hint at the reality and the violence of the conflict. The Italian propaganda agencies also produced a not insignificant number of photos and postcards, of which the ICRC archives possess approximately 50. Most of the photographs that do bear witness to the fascist violence perpetrated in Ethiopia are in private collections, which makes access to them more difficult. All this means that such visual evidence as does exist of the air raids on Red Cross units is all the more precious, not only for the history of the Second Italo–Ethiopian War, but also as regards the history of security incidents and/or war crimes perpetrated against humanitarian entities and personnel protected by the Geneva Conventions.

More pictures of the Italo–Ethiopian War in the ICRC audiovisual library.

Translation from French to English by Steve Rawcliffe.

Bibliography

Primary sources

ICRC, ACICR B CR 210– 15 Ethiopia, 1935–1936, Delegates’ report.

ICRC, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix–Rouge, Nos 401–404, January–April 1936.

ICRC, Rapport du Comité international de la Croix–Rouge sur le conflit italo–éthiopien et la Croix–Rouge, Geneva, 1936.

Brown, Sydney, Für das Rote Kreuz in Aethiopien, Zurich, 1939.

Junod, Marcel, Le troisième combattant, Paris, 1947.

L.D. (Prof.), “À propos de la visibilité du signe de la Croix–Rouge”, Revue internationale de la Croix–Rouge, No. 207, March, pp. 204–208.

Secondary literature

Albano, Caterina, “Forgotten Images and the Geopolitics of Memory: The Italo–Ethiopian War (1935–6)”, Cultural History, No. 9 (9), 2020, pp. 72– 92.

Baudendistel, Rainer, Between Bombs and Good Intentions. The Red Cross and the Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935– 1936, New York/Oxford, 2006.

Ben–Ghiat, Ruth and Fuller, Mia, (eds), Italian Colonialism, New York, 2005.

Derumeaux, Pierre, “Les représentations de la Guerre d’Ethiopie dans l’Illustration et l’Humanité”, master’s thesis, Pierre Mendès–France University, 2009.

Durand, André, History of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Volume II: from Sarajevo to Hiroshima, Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva, 1984: https://shop.icrc.org/history-of-the-international-committee-of-the-red-cross-volume-ii-from-sarajevo-to-hiroshima-print-en.html.

Gorin, Valérie, “Looking Back over 150 Years of Humanitarian Action: the Photographic Archives of the ICRC”, International Review of the Red Cross, No. 888, December 2012: https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/looking-back-over-150-years-humanitarian-action-photographic-archives-icrc.

Mallet, Robert, Mussolini in Ethiopia, 1919–1935. The Origins of Fascist Italy’s African War, Cambridge, 2015.

Pankhurst, Richard, “Il bombardamento fascista sulla Croce Rossa durante l’invasione dell’Etiopia (1935–1936)”, Studi Piacentini, No. 21, 1997, pp. 129–152.

Pankhurst, Richard, “Italian Fascist War Crimes in Ethiopia: A History of their Discussion, from the League of Nations to the United Nations (1936–1949)”, Northeast African Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1/2, 1999, pp. 83–140.

Perugini, Nicola and Gordon, Neve, “Between Sovereignty and Race: The Bombardment of Hospitals during the Italo–Ethiopian War and the Colonial Imprint of International Law”, State Crime Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2019, pp. 104–125.

Piana, Francesca, “Photography, Cinema and the Quest for Influence. The International Committee of the Red Cross in the Wake of the First World War”, in Fehrenbach, Heide and Rodogno, Davide, (eds), Humanitarian Photography. A History, Cambridge, 2015, pp. 140-164.

Notes

[1]This conflict is referred to as the Second Italo–Ethiopian War on account of the first (1895–1896), which ended in victory for Ethiopia at the battle of Adwa. In 1935, fascist propaganda drew on that event to justify Italy’s attack on Ethiopia to the public, demanding “revenge for Italy’s defeat at Adwa”. See Robert Mallet, Mussolini in Ethiopia, 1919–1935. The Origins of Fascist Italy’s African War, Cambridge, 2015.

[2]The Ethiopian Red Cross Society was founded on 25 July 1935 and recognized by the ICRC the following day.

[3]The Italian Red Cross turned to fascism in 1928 under the presidency of Filippo Cremonesi. See Rainer Baudendistel, Between Bombs and Good Intentions. The Red Cross and the Italo–Ethiopian War, 1935–1936, New York/Oxford, 2006, pp. 31–33.

[4]Ibid., p. 63.

[5]Ibid., p. 1.

[6]Ibid., pp. 176–177.

[7]Ibid., p. 74.

[8]Ibid., p. 67.

[9]The Egyptian Red Crescent Society, plus the British, Dutch, Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish Red Cross Societies.

[10]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 13 by Sydney Brown to ICRC headquarters, 15 March 1936.

[11]The historian Richard Pankhurst gives a figure of 23 (see Richard Pankhurst, “Il bombardamento fascista sulla Croce Rossa durante l’invasione dell’Etiopia (1935–1936)”,Studi Piacentini, No. 21, 1997, pp. 129–152), whereas historian and former ICRC delegate Rainer Baudendistel lists 17. The Ethiopian government also drew up several lists, one of them containing 19 attacks.

[12]Rainer Baudendistel, op. cit., p. 112.

[13]Ibid., p. 64.

[14]Nicola Perugini and Neve Gordon, “Between Sovereignty and Race: The Bombardment of Hospitals during the Italo–Ethiopian War and the Colonial Imprint of International Law”, State Crime Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2019, pp. 104–125 (p. 105).

[15]Letter from Filippo Cremonesi to the ICRC, 11 January 1936, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix–Rouge, No. 401, January 1936, pp. 74–78.

[16]Rainer Baudendistel, op. cit., p. 110.

[17]ACICR B CR 210-15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 13 by Sydney Brown to ICRC headquarters, 15 March 1936.

[18]Rainer Baudendistel, op. cit., pp. 198–199.

[19]Valérie Gorin, “Looking Back over 150 Years of Humanitarian Action: the Photographic Archives of the ICRC”, International Review of the Red Cross, No. 888, December 2012, pp. 1349–1379: https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/looking-back-over-150-years-humanitarian-action-photographic-archives-icrc.

[20]This practice of detaching photographs from the reports that they had originally accompanied began a few years after the creation of the audiovisual department by Jean Pictet in 1946. See Francesca Piana,“Photography, Cinema and the Quest for Influence. The International Committee of the Red Cross in the Wake of the First World War”, in Heide Fehrenbach and Davide Rodogno, (eds), Humanitarian Photography. A History, Cambridge, 2015, pp. 140–164.

[21]Valérie Gorin, “Looking Back over 150 Years of Humanitarian Action: the Photographic Archives of the ICRC”, op. cit.

[22]Telegram from the Ethiopian Red Cross Society to the ICRC, 9 December 1935, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, No. 401, January 1936, p. 66.

[23]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, report from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 17 December 1936.

[24]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 10 from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 20 February 1936.

[25]Telegram from Belaten Gueta Herouy to the ICRC, 13 February 1936, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix–Rouge, No. 402, February 1936, p. 159.

[26]While there were no casualties in the attacks on the Egyptian Red Crescent field hospital and Ethiopian Red Cross Field Hospital No. 1, they did suffer major damage.

[27]Rainer Baudendistel, op. cit., p. 325.

[28]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 5 from Sydney Brown to ICRC headquarters, 3 January 1936.

[29]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 2 from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 13 January 1936.

[30]Idem.

[31]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, letter from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 20 January 1936.

[32]Letter from Max Huber to Benito Mussolini, 7 January 1936, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, No. 401, January 1936, pp. 70-71.

[33]Letter from Benito Mussolini to Max Huber, 16 January 1936, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix–Rouge, No. 401, January 1936, pp. 72–73.

[34]That attack left seven people injured and damaged a quantity of medical supplies and equipment.

[35]Rainer Baudendistel, op. cit., pp. 143–153.

[36]Ibid., p. 152.

[37]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 11 from Sydney Brown to ICRC headquarters, 12 March 1936.

[38]ACICR B CR 210– 15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, letter from Sydney Brown to Étienne Clouzot, 25 March 1936.

[39]Idem.

[40]Rainer Baudendistel, op. cit., p. 144.

[41]Ibid., p. 187.

[42]After setting up camp and raising its Red Cross flags at Amba Aradam on 16 January 1936 for the purpose of providing medical services for the troops of Ras Moulougueta, the field hospital realized that it had been spotted by Italian aircraft. Fearing that his unit would suffer the same fate as the Swedish field hospital, the chief medical officer (Dr Schüppler) decided on 17 January to move the patients, the personnel and some of the equipment and supplies into a cave. As a result, the hospital that the Italian Air Force bombed the following day (18 January) contained neither patients nor staff.

[43]Max Huber, “Correspondances relatives aux bombardements aériens”, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix–Rouge, No. 402, February 1936, p. 151.

[44]See: Letter from Belaten Gueta Herouy to Max Huber in response to ICRC circular 323, Bulletin des Sociétés de la Croix–Rouge, No. 404, April 1936, pp. 308–322.

[45]Ibid., p. 203.

[46]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 10 from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 20 February 1936.

[47]Tests of this type were also conducted in Sweden, in January 1936. See: L. D. (Prof.), “À propos de la visibilité du signe de la Croix–Rouge”, Revue internationale de la Croix–Rouge, No. 207, March, pp. 204–208.

[48]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 10 from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 20 February 1936.

[49]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 13 from Marcel Junod to ICRC headquarters, 24 March 1936.

[50]Idem.

[51]Idem.

[52]ACICR B CR 210–15 Ethiopia, Delegates’ report, Report No. 12 from Sydney Brown to ICRC headquarters, 20 March 1936.

[53]Rapport du Comité international de la Croix–Rouge sur le conflit italo–éthiopien et la Croix–Rouge, Geneva, 1936, p. 8.

[54]Sydney Brown did not participate in the writing of that report, as he was dismissed from the ICRC on his return to Geneva in 1936. This was, in part, the result of tensions between him and his headquarters colleagues. As we have seen, Brown accused the ICRC of passivity. The ICRC accused him (in particular) of having passed on a confidential report to a friend and (in general) of not paying sufficient attention to the need for neutrality.

[55]Rapport du Comité international de la Croix–Rouge sur le conflit italo–éthiopien et la Croix–Rouge, Geneva, 1936, p. 5.

[56]Ibid., p. 12.

[57]Rainer Baudendistel, op. cit., pp. 195–199.

[58]Rapport du Comité international de la Croix–Rouge sur le conflit italo–éthiopien et la Croix–Rouge, Geneva, 1936.

[59]Albano, Caterina, “Forgotten Images and the Geopolitics of Memory: The Italo–Ethiopian War (1935–6)”, Cultural History, No. 9 (9), 2020, pp. 72–92, (p. 73).

[60]Derumeaux, Pierre, “Les représentations de la Guerre d’Ethiopie dans l’Illustration et l’Humanité”, master’s thesis, Pierre Mendès–France University, 2009, p. 111.

Comments