Introduction

Contrary to popular belief, the First World War did not remain in the trenches. The war had a direct impact on civilians, the economy, cities, ideas, science and the very rules that were supposed to govern the war. As the war seeped into every aspect of life, one particular practice – reprisals – had a very devastating humanitarian impact.

Reprisals were a way of both dissuading and punishing the enemy. They sometimes led to cycles of retaliatory violence – often in defiance of the law. In international humanitarian law, “reprisal” is defined as follows:

“A belligerent reprisal consists of an action that would otherwise be unlawful but that in exceptional cases is considered lawful under international law when used as an enforcement measure in reaction to unlawful acts of an adversary. In international humanitarian law there is a trend to outlaw belligerent reprisals altogether.”[1]

However, reprisals may also refer to acts and events that do not fall within the scope of existing laws.

While these reprisals were often presented as being a response to an adversary violating the laws of war, the legality of such actions was questionable [2]. Were reprisals truly effective? Were they legitimate? Or did they simply lead to an endless cycle of brutality?

This article explores different aspects of reprisals during the First World War, with a particular focus on actions that had direct humanitarian consequences, leading to the upheaval of thousands of lives. The article will then look at how the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) addressed the issue. The final section puts forward some general observations on reprisals during the Great War, which are still relevant in today’s armed conflicts.

Chemical weapons: how reprisals were used to justify an escalation in the conflict

In the 19th century, there were already attempts to curb the use of chemical weapons, including the Project of an International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War, also known as the Brussels Declaration of 27 August 1874 [3]. During the First Hague Peace Conference of 1899[4], a declaration was issued to address the use of chemical weapons, but was restricted to projectiles:

“The Contracting Powers agree to abstain from the use of projectiles the sole object of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases. The present Declaration is only binding on the Contracting Powers in the case of a war between two or more of them. It shall cease to be binding from the time when, in a war between the Contracting Powers, one of the belligerents shall be joined by a non-Contracting Power” [5].

The Hague Convention IV of 1907 also specifies that “[i]n addition to the prohibitions provided by special Conventions, it is especially forbidden (a) To employ poison or poisoned weapons” [6].

The use of chemical weapons in the spring of 1915 set off shockwaves on the battlefield and shook up international public opinion [7]. While Germany was the first to use chemical weapons, the other countries involved in the war soon followed suit. Chemical warfare became commonplace, propelled both by new technology and the widespread use of chemical weapons [8].

The chemical weapons that were initially used did not prove to be very effective and the belligerents soon sought to better target the opposing forces and use more lethal substances. In July 1917, near the town of Ypres in Belgium, the Germans used mustard gas for the first time, a substance that subsequently became known as “yperite” in reference to the nearby town[9].

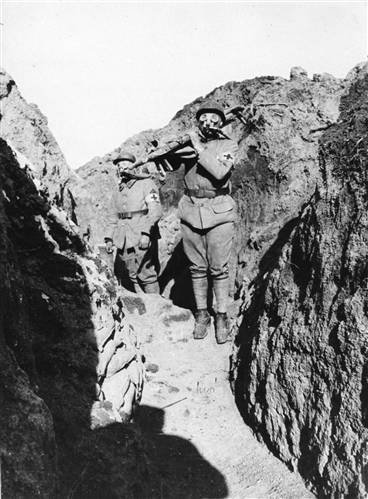

First World War. French stretcher bearers in a trench. ©ICRC Audiovisual Archives, reference No. V-P-HIST-01142-04.

From 1915 onwards, both sides accused the other of having violated international law, claiming to have only resorted to the use of poison gas to retaliate against the opposing side[10].

While chemical weapons can only account for a small fraction of deaths during the war, they had a significant psychological impact, making life for soldiers on the frontlines even more of a living hell. Reprisals became a way of justifying acts that violated the law and humanitarian principles, while also fuelling an escalation in violence.

The experiences during the First World War prompted the international community to develop laws to curb the use of these weapons. The ICRC took an active part in these initiatives, which led to the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, signed in Geneva on 17 June 1925[11].

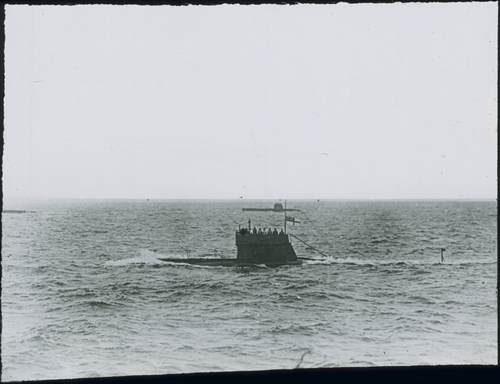

Hospital ships targeted by unrestricted submarine warfare

The commerce raiding that Germany engaged in against British merchant ships led the British to adopt certain countermeasures and strategies that made it more challenging for Germany to operate within the law, including navigating under the flag of a neutral state. To retaliate against the British naval blockade, Germany authorized its forces to attack neutral ships, violating maritime law – notably, it did not issue warnings or respect the provisions of the Hague Conventions of 1907 for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention[12].

The submarine war began on 4 February 1915, when Germany declared that all waters surrounding the British islands were now a war zone and any ships in the area could be sunk. Britain condemned Germany’s campaign as an act of piracy. Neutral states also questioned the legality of this campaign, which put their ships and trading activities in danger[13].

The most famous ship that was targeted during this period was the Lusitania, a British ocean liner that was sunk in May 1915[14]. The attack caused a scandal and the US began putting pressure on Germany to change its practices – many US citizens had been aboard the ship and the Americans even sued the German government for compensation after the war[15]. Germany was compelled to change tactics and avoid targeting passenger ships and hospital ships. Instead, it focused on the Mediterranean, where fewer US ships were present[16].

Hospital ships all over the world were attacked during this time and some ships were sunk. The belligerents often claimed to have made an error or accused their enemy of using medical ships for military purposes[17].

There was a dramatic shift in January 1917 when Germany announced to France and Britain on 29 January that it would begin engaging in unrestricted submarine warfare[18]. Germany issued a clear warning that it intended to attack and sink all ships in the English Channel and the North Sea, including hospital ships. Two days later, it extended this threat to all marine traffic surrounding Great Britain, France and Italy, as well as the eastern Mediterranean Sea.In response, France threatened to place valuable German prisoners of war on hospital ships[19].

Repatriating health-care workers: a humanitarian issue that became political

Reprisals also made it more challenging to repatriate health-care workers who fell into the enemy’s hands. Article 12 of the Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field specifies the following:

“Persons described in Articles 9, 10, and 11 will continue in the exercise of their functions, under the direction of the enemy, after they have fallen into his power.

When their assistance is no longer indispensable they will be sent back to their army or country, within such period and by such route as may accord with military necessity. They will carry with them such effects, instruments, arms, and horses as are their private property.” [20]

Some health-care workers who were captured were kept in detention to look after prisoners of war who needed medical attention. However, many of these health-care workers remained detained for months because both sides refused to comply with their legal obligations, claiming that it was the enemy who had violated the law first.

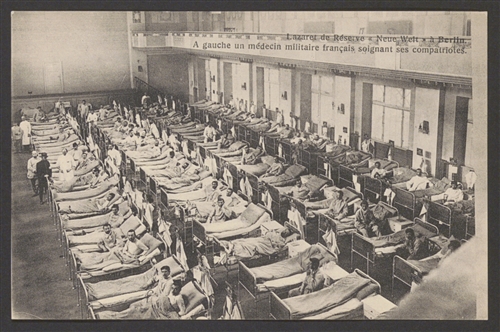

In Autumn 1914, France accused Germany of detaining French health-care workers who had been captured. Germany argued that it had captured many more soldiers than France and did not have enough doctors to address all their medical needs, so the support of French health-care workers was needed. Germany also claimed that it was retaliating against Russian and British authorities for illegally detaining German health-care workers[21]. These incidents described in the ICRC’s archives clearly illustrate how the parties involved in the conflict openly admitted that they were engaging in reprisals, without providing any other justification.

By January 1915, there was a stale mate. Both sides refused to release enemy health-care workers. Germany claimed that none of the countries were respecting international humanitarian law, putting forward an interpretation of the law that diverged from the ICRC’s interpretation[22]. While France fully agreed with the ICRC’s interpretation, it claimed that Germany had violated the law first and that it had to retaliate against Germany’s actions[23].

First World War. The ‘Neue Welt’ concert hall, Berlin, Germany. A French army doctor (far left) caring for his fellow countrymen in a reserve military hospital. ©ACICR, reference No. V-P-HIST-04004.

Some health-care workers were finally repatriated in the spring of 1915, but the situation soon stalled again.

In May 1916, it was agreed that French and German health-care workers would be interned in Switzerland, but authorities on both sides wavered, retaliating against one another by preventing the health-care workers from reaching their destination[24]. In June, Germany declared that it would only release the French, Belgian and British health-care workers it had detained if Russia released the German health-care workers it had captured[25].

By the beginning of 1917, tensions between French and Germany had reached a breaking point. Both sides accused the other of not fulfilling its legal obligations. France spoke openly of reprisals[26]. It was only in the summer of that year that countries finally began repatriating health-care workers again without encountering any major obstacles.

Sending lists of prisoners of war: yes, but only if

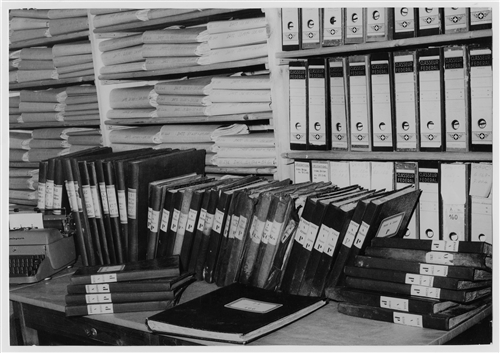

At the beginning of the conflict, the ICRC created the International Prisoners-of-War Agency based on a Resolution from the 9th International Conference of the Red Cross held in Washington in 1912[27]. The agency was in charge of gathering, storing and passing on information on the fate of soldiers.

The ICRC encouraged the parties to the conflict to submit lists of soldiers they had captured so that the authorities could pass on the information to their families.

The Germans were the first to send these lists. They expected the French to reciprocate quickly, threatening to retaliate otherwise[28]. In the early months of the war, the French were not very forthcoming with their prisoner-of-war lists, which prompted the ICRC to complain about it to the French Red Cross[29]. In order to make this exchange of lists more efficient, the ICRC suggested that the camp commanders send their lists directly to the International Prisoners-of-War Agency.

While the Germans were willing to accept this proposal, the French were more reluctant. The ICRC was afraid that there would be reprisals and began putting pressure on the French Minister of War, General Gallieni[30] – thankfully, it succeeded, illustrating the importance of reciprocity.

First World War. Rath Museum. Files from the International Prisoners-of-War Agency. ©ACICR (DR). reference No. V-P-HIST-E-03603

Persuading the belligerents to maintain reciprocity required endless dedication. The Turkish Red Crescent Society and the British government accused each other of not automatically sending the death certificates of prisoners of war who died in detention [31]. In December 1915, Germany stopped sending lists of deceased prisoners of war, just when France was finally coming around to the idea that the lists sent to the International Prisoners-of-War Agency were official death notices for families[32]. It wasn’t until July 1916 that the ICRC finally convinced the Germans and the French to exchange lists of dead detainees[33].

In the end, the ICRC’s efforts paid off. The lists of prisoners of war and deceased prisoners of war provided news to millions of families on the fate of their loved ones. Some could finally begin the grieving process.

Prisoners of war: victims of series of reprisals

The handling of prisoners of war perhaps best illustrates how there was an escalation in reprisals during the First World War. Many sources attest to this fact[34]. Some of the most notable examples will be presented below.

When the conflict began, prisoners of war were only protected by some provisions of the Hague Law[35]. It wasn’t until 1929 that a specific treaty – the Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War – was finally adopted to protect prisoners of war, based on experiences from the First World War[36].

In March 1915, the German government criticized how soldiers captured by France were being treated, threatening to retaliate[37]. A few months later, the ICRC and Switzerland offered to organize a conference between France and Germany to end reprisals involving prisoners of war. France declined[38].

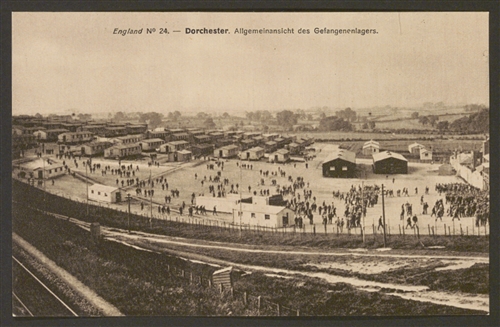

First World War. Prisoner-of-war camp in Dorset, Dorchester. Global view. ©ACICR, reference No. V-P-HIST-04124.

Reprisals also took the form of prisoner-of-war camps where prisoners were subjected to hard labour. In 1916, there was an escalation in the situation between France and Germany. Both parties justified their actions by claiming that the other side had violated the law first. When France sent German prisoners of war to labour camps in North Africa, Germany retaliated by sending French prisoners of war to labour camps in the Baltic region. As a result, France was obliged to backpedal[39].

Germany set up hard labour camps near the front lines[40], claiming that similar camps existed in France and Russia[41].

France dispersed its camps all over the country to limit the ability of neutral countries to assess the conditions of prisoners of war[42]. In May 1916, the French decided to use German prisoners of war to support the war effort and assist their army on the front lines, a clear violation of the Hague law[43]. Reprisals of a similar nature also took place between Germany and Britain[44].

The reprisals did not end until 1917. In the spring of that year, Germany decided that it would send all new French and British prisoners of war to the front lines as retaliation against the use of German prisoners of war on the front lines, including the Verdun front line. The French and the British agreed to pull back German prisoners of war at least 30km behind the front lines[45], bringing an end to the series of retaliations.

All throughout this period, the belligerents on both sides were writing to the ICRC, claiming that it was their enemy’s actions that had forced them to retaliate[46].

The ICRC’s response: neutrality, action and frustration

What can the ICRC do when belligerents engage in reprisals on various levels?

The ICRC cannot force them to respect the law. It acts as a moral authority and ca only rely on its reputation and negotiate with the parties to try to convince them to respect the law[47]. Given its limited role, reciprocity is a key part of the process.

From 19 September 1914, the ICRC began writing to the belligerents to remind them of their obligation to ensure that their armies were trained in Geneva Law[48].

On 6 February 1918, in order to curb the use of chemical weapons, the ICRC launched an appeal against the use of poisonous gases on the battlefield and suggested that an agreement be signed by the parties to the conflict[49]. Notably, it took the ICRC nearly three years to publicly denounce the use of chemical weapons on the battlefield. It finally decided to intervene because it thought that Germany was preparing a large-scale chemical attack against the Triple Entente forces[50]. It was not until 1925 that The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare was signed[51].

The belligerents accused one another of bombing quarantine stations, hospitals, hospital trains and other medical facilities. The ICRC collected charges from both sides and published them in the Bulletin[52]. In total, 32 of these charges were published between 1914 and 1919[53]. The ICRC also collected, transmitted and published complaints related to attacks on hospital ships in the Bulletin. In April 1917, with the submarine war raging once again, the ICRC called for an end to the torpedoing of hospital ships and accused Germany of intentionally violating international law[54].

As for the repatriation of captured health workers, the ICRC had lengthy, intense discussions with the belligerents. There is an abundance of correspondence on this particular topic. The ICRC first clarified its position on the role and rights of health-care workers internally[55], then shared its interpretation of the Geneva Convention with the belligerents on 7 December 1914[56]. Germany immediately declared that its interpretation of the law differed from the ICRC’s interpretation. While France agreed with the ICRC, it did not respect the law either.

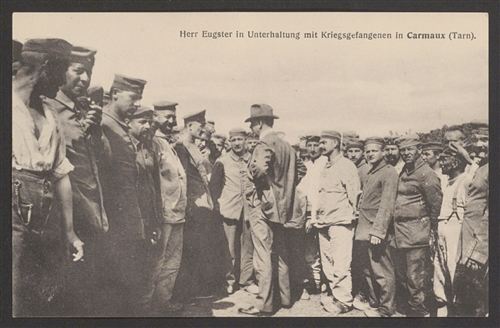

First World War. Tarn, Carmaux, prisoner-of-war camp. Mr. Eugster speaks with prisoners. ©ACICR, reference No. V-P-HIST-04140.

It is impossible to provide an overview of all the measures the ICRC took to protect prisoners of war and end the reprisals[57]. We will only focus on some aspects and events.

After carrying out inspections of prisoner-of-war camps, the ICRC pleaded for reciprocity to ensure that all prisoners of war would be treated fairly. We can see evidence of this in testimony from a delegate:

“I would like to tell you a little about the mindset of the gentlemen I am working with. It can be described with words like ‘give-and-take’, ‘reprisals’, ‘reciprocity’ and… ‘cooling down’. [58]

The warring parties were critical of the ICRC’s visits, questioning both the objectivity of delegates and the effectiveness of their work. In March 1915, the French Red Cross described how detainees could not speak freely to delegates because they were afraid of reprisals[59]. The same could be said of prisoners of war held in Switzerland. Visits from delegates had very little impact. Detainees didn’t dare to speak truthfully about the conditions in prisoner-of-war camps as they were afraid that there would be reprisals[60]. Nevertheless, the visits could sometimes help improve detention conditions[61].

The ICRC’s positive reports on British camps made it hard to justify reprisals against British prisoners of war[62]. Such reports may therefore have helped to prevent retaliatory actions.

While the ICRC worked to improve conditions for prisoners of war in general, it also specifically addressed the issue of reprisals. On 12 July 1916, it launched an appeal condemning reprisals against prisoners of war[63]. This appeal not only fell on deaf ears – the ICRC was criticized for its content. The French Red Cross complained about the general scope of the appeal, arguing that it should only concern Germany’s actions[64].

The draft of another appeal dated in 1917 can be found in the ICRC’s archives. In this draft document, the ICRC makes its frustrations clear. In particular, it takes issue with Germany for serious violations of international law and laments the fact that only Britain had openly stated that it did not want to engage in reprisals[65]. It claimed that the ICRC has a duty “to inform the world and draw first the belligerents’ attention, then the attention of all civilized nations, to serious violations of the great law of humanity” [66]. This very direct appeal – perhaps too direct – was never published.

The ICRC tried to counter reprisals by encouraging reciprocity and reducing violations of law. However, its efforts were often compromised by the belligerents who manipulated the ICRC’s reports for their own benefit.

Reprisals: curbing or fuelling the brutality?

Did reprisals discourage violations of international humanitarian law or did they lead to an escalation in the conflict?

Since reprisals by Germany in the spring of 1917 forced the Triple Entente to pull prisoners of war further back from the front lines, we might conclude that reprisals are effective and therefore a positive strategy.

But we can’t ignore how reprisals against prisoners of war continued all throughout the war, even after 1917. Other cycles of reprisals were also drawn out for years and reprisals never resolved the situation.

The human cost of reprisals is undeniable. How many people have suffered, died or had their lives destroyed because the belligerents were involved in a destructive cycle of retribution, deliberately putting their own citizens in danger?

First World War. Wahn, prison-of-war camp. French prisoners at work. ©ACICR, reference No. V-P-HIST-04097

Propaganda also negatively influenced public opinion, leading to an escalation in reprisals against prisoners of war. Dehumanizing the enemy leads societies to accept the principle of “an eye for an eye” and turn away from efforts to improve the humanitarian situation.

However, it is indeed possible that the belligerents did not treat prisoners of war as badly as they would have otherwise – but this was likely more out of fear of reprisals than because of the reprisals themselves. In some cases, this fear was probably more effective than the provisions of international law or the ICRC’s visits[67].

Can the same also be said of hospital ships? When the submarine war picked up again in 1917, the British lost several hospital ships. Conversely, France had brought German prisoners of war aboard its own hospital ships and all of its ships were spared. It’s hard to say for sure, given that the Triple Entente had decided not to put distinctive signs on their hospital ships and to have them navigate without lights.

Fear of reprisals may have limited illegal practices, but it was also used to justify such practices, allowing states to plow ahead with the violence[68]. Using reprisals to threaten the enemy may have been a bluff. But if the enemy failed to back down, states risked dragging their own citizens into violent cycles of reprisals.

Reprisals proved to be increasingly unproductive, undermining the image and legitimacy of the belligerents in the eyes of neutral countries[69]. Since these states deliberately violated international law and went against the treaties they had signed, how could they be trusted?

The nations involved in the war presented it as a struggle between civilization and barbarity, but their actions and attitude differed greatly from the principles they claimed to defend. There was not only a legal contradiction but also a moral contradiction. Given their practices, could they truly still claim to be fighting to uphold the law and civilization?

Conclusion: towards a virtuous cycle of reciprocity?

During the First World War, reprisals put the belligerents in a difficult moral and practical position. By threatening and punishing the enemy for its actions, they were also feeding a vicious cycle of violence and mistrust.

Today, reprisals against people protected under the Geneva Conventions is prohibited[70]; in situations where reprisals are not expressly forbidden by international law, they may only be carried out under very strict conditions [71].

Unfortunately reprisals are still a feature of today’s conflicts, with little regard for the law or for humanity.

A century has gone by since the First World War and we are now well aware of the human and humanitarian consequences of reprisals. The negative impact of reprisals during the First World War invites us to reflect on these practices today.

Rather than perpetuating cycles of destruction, we need to reflect on how we can foster positive reciprocity and encourage states to respect the law. Reprisals escalate tensions, making the humanitarian situation even more challenging. If belligerents instead committed to respecting the law and setting a good example, there would be fewer risks for non-combatants, including citizens, and combatants who are hors de combat.

The principle of reciprocity does not exist in international humanitarian law for good reason: even if one party does not respect its obligations, the other parties are still required to do so. However, the concept of reciprocity can also be applied more constructively. We should work towards implementing virtuous cycles of reciprocity based on the respect of international law. That way, belligerents can not only display their commitment to the law and humanity, but also encourage others to follow their example[72]. Refusing to engage in reprisals is not just a question of law – it’s about choosing humanity over vengeance, even in the midst of a war.

[1] Customary international humanitarian law, rule 145, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/customary-ihl/v1/rule145

[2] With regard to the international law that was in effect during the First World War and how that law was both violated and respected, see: Isabel V. Hull, A Scrap of paper. Breaking and Making International Law during the Great War, Ithaca/London, Cornell University Press, 2014; Jean H. Quataert, “International Law and the Laws of War”, in Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer and Bill Nasson (eds.), 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, 2014: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/international-law-and-the-laws-of-war/

[3] In particular, Article 13: “According to this principle are especially ‘forbidden’: a) Employment of poison or poisoned weapons”, Project of an International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War, Brussels, 27 August 1874, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/brussels-decl-1874; see also Catherine Jefferson, “Origins of the norm against chemical weapons”, International Affairs, Vol. 90, No. 3, May 2014, pp. 647–661: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1468-2346.12131

[4] Thomas I. Faith, “Gas Warfare”,1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/gas-warfare/

[5] Declaration (IV,2) concerning Asphyxiating Gases, The Hague, 29 juillet 1899 : https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-decl-iv-2-1899

[6] Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, The Hague, 18 October 1907, Article 23, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-conv-iv-1907/regulations-art-23

[7] Olivier Lepick, La Grande Guerre chimique: 1914–1918, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1998, p. 297.

[8] Ibid., p. 234.

[9] Ibid., p. 218.

[10] Annie Deperchin, “Les gaz et le droit international”, in Laura Maggioni (ed.), Gaz! Gaz! Gaz! La guerre chimique, 1914–1918, Milan, 5 Continents Editions, 2010, p. 21; also an exhibition at the Historial de la Grande Guerre museum in Péronne in 2010. For a more detailed analysis on the debate surrounding the use of chemical weapons before, during and after the First World War, see: Miloš Vec, “Challenging the Laws of War by Technology, Blazing nationalism and Militarism: Debating Chemical Warfare before and After Ypres, 1899–1912”, in Bretislav Friedrich, Dieter Hoffmann, Jürgen Renn, Florian Schmaltz and Martin Wolf (eds.), One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences, Cham, Springer, pp. 105–134: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-51664-6_7

[11] Leo van Bergen and Maartje Abbenhuis, “Man-monkey, monkey-man: neutrality and the discussions about the ‘inhumanity’ of poison gas in the Netherlands and International Committee of the Red Cross”, First World War Studies, Vol. 3, 2012, pp. 1099–1120.

[12] Convention (X) for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention, The Hague, 18 October 1907: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-conv-x-1907

[13] Mark D. Karau, “Submarines and Submarine Warfare”, 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/submarines-and-submarine-warfare-1-1/

[14] Chelsea Autumn Medlock, “Lusitania, Sinking of”, 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/lusitania-sinking-of-1-1/

[15] The Lusitania surfaces multiple times in the agreement of 10 August 1922, which defined Germany’s financial commitments under the US –German Peace Treaty: Mixed claims commissions United States–Germany constituted under the Agreement of August 10, 1922, extended by Agreement of December 31, 1938, https://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/vol_VII/1-391.pdf

[16] Mark D. Karau, “Submarines and Submarine Warfare”.

[17] Cédric Cotter, (S’)Aider pour survivre. Action humanitaire et neutralité suisse pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, Chêne-Bourg, Georg Editeur, pp. 60–62.

[18] Michael S. Neiberg, “1917 : Mondialisation”, in Jay Winter (ed.), The Cambridge History of the First World War, Vol. 1: Global War, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 110.

[19] J. Galloy, L’inviolabilité des navires-hôpitaux et l’expérience de la guerre 1914–1918, Paris, Libraire du Recueil Sirey, 1931, p. 103.

[20] Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field, Geneva, 6 July 1906, Article 12: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/gc-1906/article-12

[21] ICRC Archives (ACICR), C G1 B 02-06.09, Letter from the ICRC to the Russian Red Cross Society in Petrograd, 8 February 1915.

[22] ACICR, C G1 B 02-05.01, Letter from the House of Representatives in Berlin to the ICRC, 23 January 1915.

[23] ACICR, C G1 B 02-05.01, Letter from the French Ministry of War to the ICRC, 2 March 1915; ACICR, C G1 B 02-06.01, letter from the ICRC to the German Red Cross’ prisoner of war commission, 24 March 1915.

[24] ACICR, C G1 B 02-06.01, Letter from the ICRC to the German Red Cross’ prisoner of war commission, 31 May 1916.

[25] ACICR, Letter from the ICRC to the Belgian minister in Bern, 9 June 1916.

[26] ACICR, C G1 B 02-06.01, Letter regarding the general inspection of prisoners of war from the French ministry of war to the ICRC, 7 April 1917.

[27] Gradimir Djurovic, The Central Tracing Agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross: Activities of the ICRC for the Alleviation of the Mental Suffering of War Victims, Geneva, Henry Dunant Institute, 1986, p. 40.

[28] Telegram from Gustave Ador to the Federal Political Department, 19 September 1914, Swiss Federal Archives, 1000/45, bd. 89, No. 692.

[29] ACICR, C G1 A 11-01, Letter from the ICRC to the central committee of the French Red Cross in Bordeaux, 16 November 1914.

[30] ACICR, C G1 A 11-01, Letter from the ICRC to the French Minister of War, General Gallieni, 17 January 1915; Frédéric Barbey, L’agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre à Genève, Bern, K.J. Wyss, p. 87.

[31] See documents in ICRC Archives, C G1 A 13-01.

[32] ACICR, C G1 A 13-03, Letter from the French Ministry of War to the ICRC, 4 December 1915.

[33] ACICR, C G1 A 13-01, Letter from the quartermaster, head of the bureau of intelligence of the Ministry of War, to the ICRC, 6 July 1916.

[34] Uta Hinz, “Prisonniers”, in Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Jean-Jacques Becker (eds.), Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre 1914–1918, Histoire et culture, Paris, Bayard, 2000, pp. 778–779; Heather Jones, Violence against Prisoners of War in the First World War: Britain, France and Germany, 1914–1918, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011. See also Chapter 9 of Isabel V. Hull, A Scrap of paper. Breaking and Making International Law during the Great War, Ithaca/London, Cornell University Press, 2014, p. 276 et seq.

[35] On the development of Geneva law and Hague law during the First World War, see “Conventions internationales et droit de la guerre”, in Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre 1914–1918, Histoire et culture, pp. 83–95; Isabel V. Hull, op. cit.

[36] Hazuki Tate, “Hospitalization, internment, and repatriation: Switzerland and prisoners of war”, Relations internationales, No. 159, autumn 2014, pp. 35–47; Neville Wylie and Lindsey Cameron, “The Impact of World War I on the Law Governing the Treatment of Prisoners of War and the Making of a Humanitarian Subject”, European Journal of International Law, Vol. 29, No. 4, 2018, pp. 1327–1350: https://academic.oup.com/ejil/article/29/4/1327/5320163

[37] ACICR, C G1 A 18-06, Letter from the Ministry of War in Berlin to the Hamburgischer Landesverien vom Roten Kreuz, translated by the ICRC, 24 March 1915.

[38] ACICR, C G1 A 09-04, Letter from the ICRC to the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 7 August 1915; letter from the French ambassador in Bern to the ICRC, 24 August 1915.

[39] All examples from Heather Jones, “Prisoners of War”, 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/prisoners-of-war/

[40] Heather Jones, “The German Spring Reprisals of 1917: Prisoners of War and the Violence of the Western Front”, German History, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2008, pp. 339–340.

[41] Report from Dr A. Schulthess and F. Thormeyer on their visit to Russian prisoner of war camps in Germany in April 1916, Vol. 11, Geneva, Librairie Georg & Cie, July 1916, p. 4.

[42] Ronan Richard, La nation, la guerre et l’exilé. Représentations, politiques et pratiques à l’égard des réfugiés, des internés et des prisonniers de guerre dans l’Ouest de la France durant la Première guerre mondiale, PhD thesis, Université Rennes 2, 2004, Vol. 2, p. 508.

[43] Heather Jones, “The German Spring Reprisals of 1917”, p. 343.

[44] Heather Jones, “Prisoners of War”.

[45] Ibid.

[46] For example, see documents in ICRC Archives, C G1 A 21-01.

[47] See Lindsey Cameron, “The ICRC in the First World War: Unwavering belief in the power of law”, International Review of the Red Cross, No. 900, November 2016, https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/icrc-first-world-war-unwavering-belief-power-law

[48] Minutes from Meetings of the International Prisoner-of-War Agency, 19 September 1914.

[49] Appeal against the use of poisonous gases, ICRC, 6 February 1918: https://international-review.icrc.org/fr/articles/appel-contre-lemploi-des-gaz-veneneux

[50] For a critical look at this period, see Cédric Cotter, (S’)Aider pour survivre, pp. 50–54.

[51] Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, Geneva, 17 June 1925, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/geneva-gas-prot-1925

[52] For example, see ICRC Archives, A CS 5. On the ICRC’s practice of publishing complaints from belligerents in its Bulletin, see Lindsey Cameron, “The ICRC in the First World War: Unwavering belief in the power of law”.

[53] Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross on its activities from 1912 to 1920, ICRC, 1921, pp. 14–16.

[54] ACICR, A CS 3.1, Note from the International Committee of the Red Cross to the German government on the torpedoing of hospital ships, 14 April 1917.

[55] ACICR, C G1 B 02-06.03, Report presented by Ms. Ferrière and Ms. D’Espine to the president of the international committee for health-care workers imprisoned by the enemy, n.d.

[56] Minutes from Meetings of the International Prisoner-of-War Agency, 7 December 1914. See also ACICR, C G1 B 02-05.01.

[57] For additional information, see “The ICRC during World War I, Cross-Files, 3 June 2019: https://blogs.icrc.org/cross-files/the-icrc-during-world-war-i/; François Bugnion, Confronting the hell of the trenches: the International Committee of the Red Cross and the First World War, 1914–1922, Geneva, ICRC, 2018.

[58] ACICR, C G1 A 19-04, Letter from Carl de Marval to Gustave Ador, 8 January 1915.

[59] ACICR, C G1 A 18-15, Letter from the French Red Cross to Gustave Ador, 5 March 1915.

[60] See various documents in ICRC Archives, C G1 A 43-05.06.

[61] Heather Jones, “A Missing Paradigm? Military captivity and the Prisoner of War, 1914–18”, Immigrants & Minorities, Vol. 26, No. 1–2, March–July 2008, p. 34.

[62] Matthew Stibbe, “Civilian Internment and Civilian Internees in Europe, 1914-20”, Immigrants & Minorities, Vol. 26, Nos. 1–2, March–July 2008, p. 73.

[63] ACICR, C G1 A 06-06.02, Note of 12 July 1916; Minutes from Meetings of the International Prisoner-of-War Agency, 12 July 1916. See also ACICR, A CS 2, declaration from the ICRC regarding reprisals against prisoners.

[64] ACICR, A CS 2, Letter from Gustave Ador to the Marquis de Vogüé, 5 September 1916.

[65] ACICR, A CS 2, Declaration of the ICRC regarding reprisals against prisoners.

[66] Ibid.

[67] John Horne, “Atrocities and war crimes”, in Jay Winter (ed.), The Cambridge History of the First World War, Vol. 1, p. 561.

[68] Annie Deperchin, “The laws of war”, in The Cambridge History of the First World War, Vol. 1, p. 615.

[69] Heather Jones, “The German Spring Reprisals of 1917”, p. 353.

[70] First Geneva Convention (1949), Art. 46; Second Geneva Convention (1949), Art. 47; Third Geneva Convention (1949), Art. 13, para. 3; Fourth Geneva Convention (1949), Art. 33, para. 3; IHL customary law, rule 146: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/customary-ihl/v1/rule146

[71] IHL customary law, rule 145, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/customary-ihl/v1/rule145

[72] This is the objective of the IHL in Action database, which aims to “encourage the reporting, collection and promotion of instances of respect of IHL” : https://ihl-in-action.icrc.org/

Comments