When it comes to answering the needs of people with disabilities, an essential part of the ICRC’s response is building physical rehabilitation centres (PRCs).

Over the past three decades the ICRC has become an expert in the field, setting up on average one new PRC programme a year and developing a wealth of knowledge and experience in the process.

This has now been brought together in a book, Physical Rehabilitation Centres: Architectural Programming Handbook, which is drawing attention not just from the humanitarian and development sectors but also from architects and engineers. It will be presented at the congress of the International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics, in Lyon in June.

In this interview, Adam Beaumont finds out more about the book from Samuel Bonnet, head of construction in the ICRC’s Water and Habitat Unit:

Can you gives us a bit more insight into what this book is about?

The physical rehabilitation activities of the ICRC can be traced back to the Second World War, and the institution has been actively building physical rehabilitation centres over the past 30 years.

The primary aim of this handbook is to provide support for all those who are involved in the building or renovation of a PRC operated by, or with the support of, the ICRC. Its central theme is the development of an architectural programme for a PRC.

What do you mean by “architectural programme”?

An architectural programme is a crucial moment in the life of a construction project when you express the aims and limitations in technical terms for the people who will operate it, such as the Physical Rehabilitation Project (PRP), orthopaedic and physiotherapy teams. These form part of the “cahier des charges” for the architect when he or she comes to design the building.

Before the book, this procedure was often complicated by the fact that, here at the ICRC, we don’t all speak the same language and therefore it’s sometimes difficult to understand each other. So this book’s aim is to provide a common platform of understanding for all our teams.

How difficult was it to put this book together?

Once we’d decided that we needed a common set of guidelines, we then went back to find examples of best practice from the history of PRP and the Special Fund for the Disabled (SFD). We searched the archives and interviewed a lot of people to find out which centres were good and why.

We gathered photos and plans, but sometimes we couldn’t find a great deal because it hadn’t been archived. So we had to redo the plans for some of the buildings from scratch and interview people working in those centres to find out what works and what doesn’t.

The second chapter of the book takes an in-depth look at 10 PRCs, examining why and how they were built. Each centre can be compared one against the other, so it’s easy to work out, for example, how many people you would need to staff a centre of such and such a size or how much land you would need to build it.

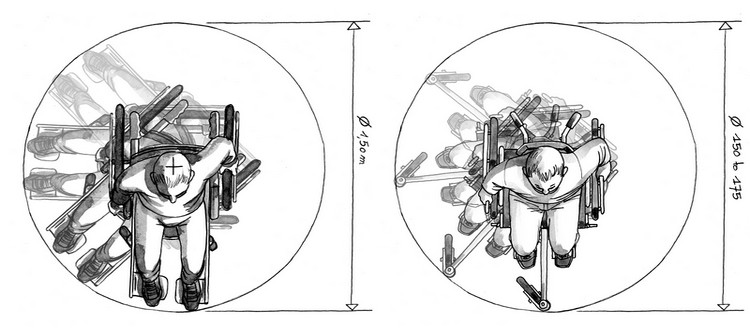

Manoeuvring spaces for four-wheeled and three-wheeled wheelchair, based on international norm and ICRC evaluation. Pierre_Antoine Thierry/MEDDE

What else does the book contain?

The book also defines how a centre should function, service by service. There are diagrams showing how to design everything from the plumbing, electricity and ventilation, to the size of doors and the minimum amount of equipment needed for each room.

It sets out what areas you need, such as physiotherapy/exercise rooms, assembly rooms, toilets, prayer rooms and sleeping accommodation. There is also a strong focus on accessibility, because a PRC can be used independently by beneficiaries, thus helping with their social integration. It all adds up to a blueprint for the ideal physical rehabilitation centre, right down to the smallest detail.

Who will use this book?

In the first instance, it’s for WatHab and PRP colleagues. But we rarely build a centre just for the ICRC: we build them with the authorities in a country. So the book is also for health ministries and governments, to show them what we have done in other contexts and to help explain what we plan to do with them.

It will also be useful for other humanitarian and development organizations, because when you build a PRC in an emerging country there really isn’t a standard reference book on how to do it.

It will also be of interest for engineering and architecture schools. When I meet architects and engineers outside the  ICRC, they tend to think that we still build shelters out of canvas; when I show them the book, they are surprised to see what we are doing in terms of building infrastructure.

ICRC, they tend to think that we still build shelters out of canvas; when I show them the book, they are surprised to see what we are doing in terms of building infrastructure.

Finally, to specialists and non-specialists, this handbook explains how to build an appropriate environment that is essential for laying the foundations for the broader integration of beneficiaries back into their community.

This publication can be ordered or downloaded online.

Download other recent publications by clicking the following link:

Handbooks on Frameworks for Protection of Health Care & Partnering for Humanity

More on ICRC’s physical rehabilitation work:

Myanmar: Restoring mobility in local communities

Afghanistan: Football is making a difference

Surviving landmines: Edisson’s road to recovery

Bangladesh: A doctor in the making

Sri Lanka: Sustaining the work of the Jaffna Jaipur Centre into the future

Follow the ICRC on facebook.com/icrc and twitter.com/ICRC_nd