In this Digital Dilemmas 2.0: Deepfakes episode, we take a look at two poignant questions: “How do we distinguish truth from manipulation? Who owns the truth?“

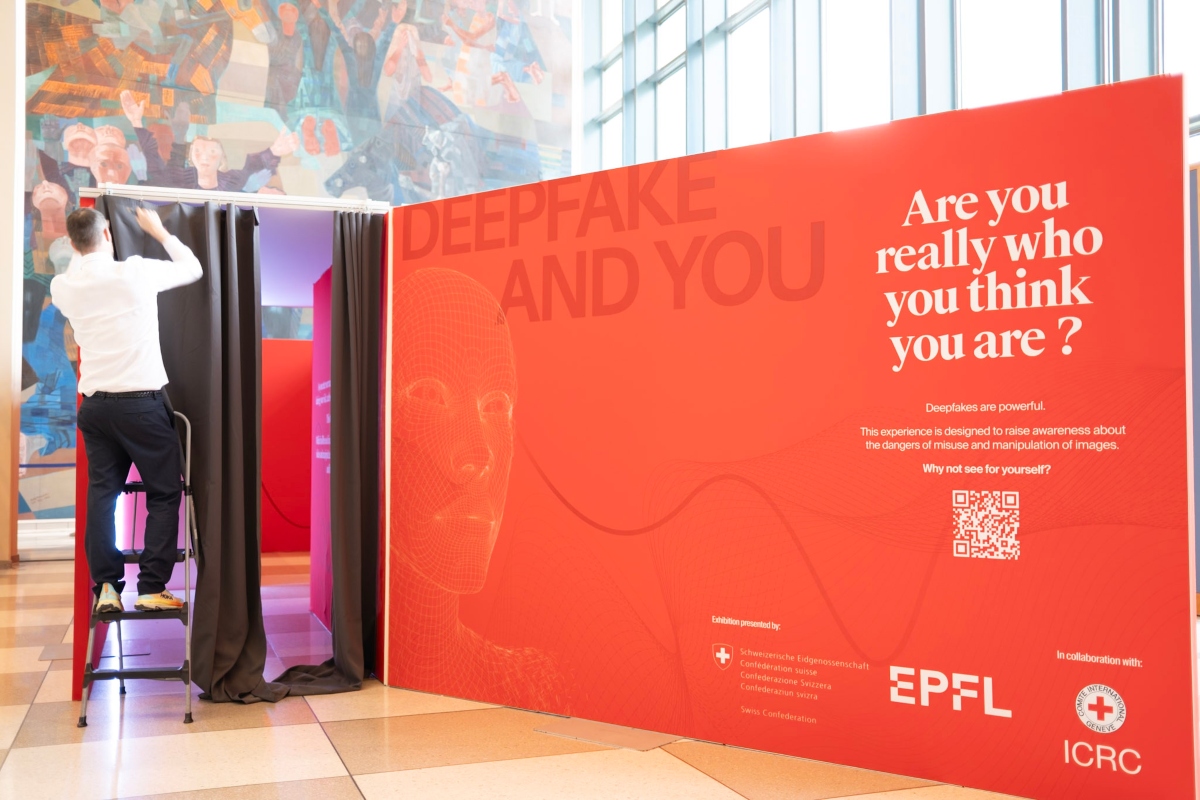

We tour a deepfake exhibit created by the ICRC and L’École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) at the United Nations. Then, we zoom out and look at how dissemination of harmful narratives projected in images, videos, or other information affect communities in conflict and situations violence.

The Deepfake and You Exhibit at the UN General Assembly in New York in October. Photo Credit: Yuriy Shafarenko

Entrance to the Deepfake and You exhibit. Photo Credit: Yuriy Shafarenko

ICRC Techplomacy Delegate Philippe Stoll shows Swiss Foreign Affairs Minister, Ignacio Cassis, around the exhibition. Photo Credit: Yuriy Shafarenko.

Important Links

Handbook on data protection in humanitarian action

From content to harm: how harmful information contributes to civilian harm

Foghorns of war: IHL and information operations during armed conflict

Episode readout for the hearing impair

[BONESSI] I recently had an AI generated video version made of me. While it was a far-off audio version, coming from a spot-on clone of me, it did get me thinking about two poignant questions. I’ll let AI-generated me ask them.

[AI Generated Dominique] “How do we distinguish truth from manipulation? Who owns the truth?”

On today’s episode, we’ll take on those questions and more as we deep dive into deepfakes. Then we zoom out and look at how dissemination of harmful narratives projected in images, videos, or other information, affect communities in conflict and situations violence.

I’m Dominique Maria Bonessi and this is Intercross. A podcast that gives you a window into the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross and shares the stories of those affected by conflict and other situations of violence.

[INTERCROSS MUSICAL INTERLUDE]

[Peter Gronquist at Exhibit Tour] “So we’re at the UN right now. And I’m about to give you a short tour of this deep fake exhibit that we’ve been setting up with ICRC and EPFL.”

[BONESSI] Peter Grönquist is a research software engineer with the Image and Visual Representations Lab at the Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (or EPFL for short), it’s basically the MIT of Switzerland. The ICRC is working with EPFL to explain and find solutions to deepfakes and other technologies disseminating harmful information among populations in conflict areas.

You might remember last season, we dove into the massive impact of digital technologies for people who are affected by conflict, disaster, or both. As the ICRC we encourage people and decision-makers to –think through these types of situations and learn to mitigate risks.

And that’s why I’m standing with Peter next to a loud set of escalators in a foyer of the United Nations’ general assembly building in front of this large red, 3D square saying deepfake and you. Are you really who you think you are?

[PETER] “So once we enter this, large red square, that hopefully caught your attention, You’ll be greeted by another disclaimer with a large, exclamation point that tells you that there are deepfakes that are being made in this exhibit. And uh, if you don’t want deepfakes of yourself, you should go back. And actually this is a little trick that we put in. And the idea is that there is a little camera hidden in the exclamation point that will capture your face as you walk in and read this sign. So it’s a little bit of a joke.”

[BONESSI] “So I’m reading the sign and then the bottom thing is we do not store any data or images, but this experience might be disturbing to you. So, warning. And if you don’t want to continue, please turn back now is in big red letters.”

[PETER] “So after we’ve, we’ve, uh, raised your awareness, we, we calmed you down with this very relaxing painting. And here, actually, what happens is that we have another webcam that performs, that captures you and then transforms you into this, style of Arcimboldo.”

[BONESSI] That’s Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the 16th century renaissance painter.

It is pretty relaxing. I’m seeing, you know, myself, and there’s all sorts of produce being put on my face, um, and apples and, um, my clothes look like they’re changing colors. I go from being a curly haired person to a long-haired person to a, uh, to a, from a boy to a girl again.

[PETER] “You can play around also if you put, like, objects in front of the camera, it will try to, to hallucinate something. In theory, this is actually based on a text prompt. So if you wanted, we could have put a keyboard out here, and then you just enter whatever text you want, and it will transform you.”

[BONESSI] So, for example, if I said, like, make me, uh, the Mona Lisa. Yeah. I could, I could put my, you could put my face into the Mona Lisa?

[PETER] “As you type it will immediately transform you. Yes.”

[BONESSI] So some of the beauty of AI, but also we’re going to learn about some of the consequences, right?

[PETER] “Exactly.”

[BONESSI] We move on to the back wall of the exhibit lined with historical photographs some dating back to as late as the 16th century. You could recognize some of these from your high school history textbook. All of them have been edited or distorted in some way.

It’s clear, the technology used to distort or edit images and video has gotten more complex, but historically there’s always been some desire to edit or distort images. We turn a corner and see a photo from the American Civil War with General Ulysses Grant standing on the battlefield on his horse,

[PETER] “But actually it’s based on a picture of him standing in a tent. [chuckles] This has always been happening. People always wanted to change a little bit reality. But, uh, what’s interesting is that we’ve always actually accepted, um, images and videos as truth, which is, has never been the case. Firstly, it’s a capture of, some capture of reality, and then we’ve, it’s immediately edited just by the processing pipeline in the camera. I mean, it’s something we learned, right, in our high school. If you want to analyze history, you need to look at many sources and then see from there. Is it trustworthy or not? It’s, you can’t just accept it because it’s close to what you would want the reality to be. It has to be questioned.”

[BONESSI] Peter explains there are a few ways to detect deepfake images with the naked eye and pulls up a very viral image on his iPad. It’s one I have definitely fallen for in the recent past.

[PETER] “There is this picture of the Pope, which you might have seen. (BONESSI: Oh Yes)

[BONESSI] This deepfake image shows Pope Francis walking down a street in the Vatican wearing a stylish puffy, white coat. Peter says it shocked people because of how real it looked, but upon a closer look you’ll see many issues with the image.

[PETER] “There’s, like, a coffee cup floating in his hand. Um, at some point he has a belt, the second image there is no belt, uh, the glass shadows make no sense, also in one picture he has no legs, but you just don’t question it, because to you, you think, oh, this may be some artifact from the camera, uh, it’s, it’s realistic, but in, in reality it’s, it’s not, right, it’s fake.”

[BONESSI] But Peter says there are a lot of issues with images that may not be visible to the naked human eye. And that’s where solutions-based AI machines come in and people like Peter.

[PETER] “AI to solve problems that AI has created. It’s basically an arms race, a little bit. If we now publish all our deepfake detection, um, AIs, The deepfake creators can also just use those to train their defect generation AIs. (BONESSI: To get past them.) Yes, exactly.”

[BONESSI] This arms race Peter is talking about isn’t some long-shot futuristic issue, it’s our present.

And just in case that didn’t freak you out enough, the last part of the exhibit took the cake.

We walk to the end where an image of my face pops up on a screen and starts talking to me.

[AI-Generated Dominique] “Hey, how are you? You really look like me. How do you feel? Are you surprised? Are you annoyed? Are you angry? In fact, I know how you feel because I’m you. And with that, I can call your family for example and ask for money. Or I can use your face to call for genocide. So what do we do with that? How do we distinguish truth from manipulation? Who owns the truth?”

[BONESSI] While the voice doesn’t sound like me, it would be easy for someone to get a deepfake version of me with my voice, as host of this podcast, and combine it with a photo online, and bam. I’m saying things, I have never said before.

But figuring out truth from manipulation in conflict and other situations of violence isn’t just an issue with deepfakes.

To talk more about this, I sat down with my colleague Laura Walker McDonald, the ICRC Washington Delegation’s Senior Advisor on New Technologies in Conflict. Laura’s been on the podcast before and she’s back with us now to talk through some of the deepfakes that we just saw in the exhibit and other harmful information.

[BONESSI] So Laura, why is the ICRC concerned with the spread of harmful information like deepfake images or video or just misinformation online in areas of conflict and other situations of violence?

[MCDONALD] Thank you for having me back. Yes, so we are concerned about harmful information wherever it crops up, could be online, could be radio, could be other information channels, and we see four serious risks that we would highlight that are linked to harmful information. First of all, harmful information can have direct, humanitarian consequences for people. It can lead directly to physical, psychological, economic, and social harms, either by misdirecting people away from life-saving information that can help them get the services and assistance they need or keep them away from somewhere where they might come to physical harm.

It can lead to people being directly targeted or harassed or it can actually subject them to Discrimination and dehumanization which can jeopardize their sense of dignity But also in conflict which can put them directly in harm’s way from other people. In that way, second risk, it can fuel conflict dynamics.

So it can fuel hatred and, particularly, sort of directed at certain groups and it can encourage violence towards those groups and, and therefore again, put people in harm’s way. But there can be a sort of escalatory effect, especially now where online information can go viral and can move very quickly and narratives can spin up very fast and that can actually. Accelerate conflicts and even trigger specific events in conflict.

But more than that, it can actually. Speed up and accelerate and impact conflict dynamics and even trigger specific events in conflict. It can also then, you know, once the information environment is polarized and contested, it can undermine the opportunity to achieve a conflict resolution and find peace.

And then, a third risk that we would highlight is, the risk to, the law . So it can actually undermine the application of international humanitarian law and other Relevant legal framework. So, for example, by encouraging violations of international law.

And then finally, we do see a serious risk to humanitarian workers where, information about humanitarian workers, which undermines community trust in humanitarians, or spreads a sort of misinformation about the role and mandate of humanitarian workers can reduce the safety of humanitarian workers going to certain places.

And that might mean that they would not be able to go there because it wouldn’t be safe. We do have a duty of care to our staff and so, if we think there’s an increased risk, we may not be able to go and do our humanitarian work, whether that’s providing assistance or protection, which would mean that then we aren’t able to give that assistance and protection and that would be bad for the populations involved.

It can directly lead to violence, against humanitarian aid workers, which can put them at serious risk as well.

[BONESSI] Can you give me some other examples of trends that we’ve seen in conflicts and other situations of violence around the world where harmful information has had direct effects on civilian populations?

[MCDONALD] So you can see this across different channels and different conflicts for sure, but for example, you might see misleading sms campaigns that give False information about things like evacuations to civilians and we had that exact example in our digital dilemmas exhibition in washington last year. You might see radio messages that are sharing misleading information about say humanitarian actors, um, and what they’re doing in such a way that it puts them in harm’s way. Or you might see online platforms publishing photos and videos of prisoners of war, which would also not be in compliance with international humanitarian law.

[BONESS] So this exhibit on deepfakes at the UN made it feel like it’s just the wild, wild west of technology and, and there are no rules and, and we’re just deregulated entirely. Is, is that true?

[MCDONALD] Yeah, I can see how I can feel that way. There’s, there’s a lot of talk at the moment about different potential regulatory approaches and different places and basically everyone’s trying to figure out what the right answer here is because it is very difficult and challenging.

But the good news is there are rules that apply. For example, International humanitarian law applies online as it does offline and IHL does regulate, the way that, states can and parties to conflict can use information. And it also protects the life and dignity of affected people affected by conflict.

International humanitarian law, IHL, does impose clear limits on information operations in armed conflict. For example, that encourage unlawful forms of violence, that share information about the recruitment of children, of child soldiers, that publish images of prisoners of war, that intentionally spread fear and terror or that obstruct and undermine humanitarian operations.

[BONESSI] In conflict, we often see that various groups have various different versions of the truth. I put that in air quotes very lightly. So how does the ICRC parse that as a neutral, independent and impartial organization?

[MCDONALD] Clearly this is a challenge because we do want to monitor the spread of, of information, harmful information and talk to people about some of these challenges around the information environment, but at the same time, it’s not our job to say what the truth is.

Our job is to provide life-saving humanitarian information and to make sure that our role and mandate is clear. And we want people to have the information so that they can draw their own conclusions and make decisions that seem right to them in a…what are often, very challenging environments.

It’s very important to have open dialogue, and diverse perspectives represented in the information environment. I think where we try to draw this chart, this difficult course is by encouraging everyone to be aware of those harmful potential risks and consequences that I outlined earlier and understanding that whatever role they play in the information ecosystem, whether that’s as a producer of content, whether that’s as someone who runs a platform where content is posted, or whether that’s just you and me every day as consumers of information, that we understand those risks and we can do what we can do to try to limit those potential harms.

We also need to operate within the legal rules that protect people who are caught up in conflict, but I think for all of us understanding media literacy that we’re all called upon to bring to bear when we’re absorbing content. So thinking critically about what we’re seeing and, asking questions and hitting pause before we share content and thinking about whether it might be true, that’s really important.

Those are important skills. Those can be taught and those kinds of, media awareness, content reminders, even courses, can be very helpful and we also support any attempt to identify and then promote accurate information. That’s very helpful. And we try to do that as well. And then for us, we try to make sure that we share information about who the ICRC is, what we do about humanitarian principles and our neutrality, impartiality, and independence, so that people can understand who we are and what we do and it helps to keep our staff and volunteers in the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement safe as well as the people that we seek to serve.

[BONESSI] Entities that amplify information, like social media companies, also play a role in conflict in situations of violence. What responsibilities do they have?

[MCDONALD] So companies will have to be compliant with the national law and the international law, um, that applies to them in the countries where they’re operating and where they are headquartered. Um, and we also, uh, would point to the UN guiding principles on, um, business and human rights.

As something that companies should always have an eye to, as well as other applicable laws and rules and guidelines. Um, but generally we encourage companies to have, to take a conflict sensitive approach where appropriate to things like content moderation. So balancing human rights online with having awareness of the risks of harm that might be elevated or different in conflict contexts, and also being aware of what it would take to be compliant with international humanitarian law.

For us, when we engage with those companies, we’re definitely trying first and foremost to, to make sure they’re aware of us, the ICRC, and, and our role and mandate, but also of what is contained in international humanitarian law and how those companies can, um, help, um, mitigate the potential harms and humanitarian consequences of the information on their platforms.

[BONESSI] One of the solutions to deep fakes that I discussed with Peter Gronquist at the exhibit was putting a watermark on an image or video to indicate to the viewer that it’s fake, but that might still not convince someone, a viewer, that the image is not to be trusted. Why is that?

[MCDONALD] Yeah, so watermarks can be a really good tool in the toolbox. And, um, I guess it’s kind of like if you see like a mark of or a certification on like a carton of milk or something that says that it’s well made and that it complies with certain standards. So if you think about something like that, a watermark would have to come from somewhere.

It would have to mean something, it would have to indicate some kind of quality or equally it could indicate that something had been digitally manipulated and I think for both of those things to be useful in this context of this very complex information environment where people are trying to decide whether a particular piece of content is any good or not they’d have to understand what the watermark went.

And that’s it. meant and where it had come from, who’d made it and have trust in that provider. So I guess in that way, it depends on then, you know, the work being done to raise public awareness of those watermarks and, and make sure that they trust them. But I think still, you know, if something, let’s say something was watermarked or it said in some way, this has been generated and it is not true.

If it could still be very inflammatory, it still could be that it doesn’t, it doesn’t do anything about the habit we have as humans to be more likely to believe information, even if it’s not true, if it’s in line with what we already believe. And we know that these biases exist, and I don’t think necessarily watermark is going to do too much to that.

So I think, again, it has to be hand in hand with, you this work to increase media literacy and the habit of pausing and evaluating, critically assessing information before you act on it.

[BONESSI] And for other information, other harmful information that’s not an image or video, Is there a low tech solution to a high tech problem to lessen the impact of harmful information in conflict?

[MCDONALD] You know, all of these channels, whether it’s SMS or radio or deep fakes on YouTube, or deep fakes on a video platform, they can all. Be true or false or built into a narrative that is harmful. And I think the most effective technology that can come combat that is actually just people. Again, it’s investing in that . It’s also working with and through trusted community leaders. And sometimes that’s our red cross and red Crescent movement itself.

It’s the national societies that have each country that who are those community leaders who are trusted to share accurate information in a really critical moment. That can help save lives. I think you have to always assess what is the most appropriate technology channel to be communicating in a given place.

Make sure that you’re talking to everyone in a community and make sure that you are also working with community leaders to share the life-saving information that we as humanitarians want to get out there.

[BONESSI] Thank you Laura.

[MCDONALD] Thank you so much for having me.

[BONESSI] And thank yous for this episode go to Peter Grönquist and Gaël Hurlimann from EPFL, Laura Walker MacDonald, Jonathan Horowitz, Joelle Rizk, Yuriy Shafarenko,Thomas Glass, and Philippe Stoll.

That’s our show for today, please if you like the content you get here on Intercross, please do me a favor and rate, review, and subscribe. Tell us what you think about the podcast, are there particular contexts or issues you think we should talk about.

And, if you want to learn more about digital dilemmas you can visit us at intercrossblog.icrc.org. There you can also have a newsletter you can subscribe to, so you never miss a podcast.

You can also follow us on X.com @ICRC_DC to read more about our work with new technologies in conflict.

See you next time on Intercross.