In this episode, we tell the story of the more than 150-year-old Central Tracing Agency, a division of the ICRC that today is a crucial resource for families searching for loved ones gone missing due to conflict, violence, natural disasters, or along the migration route. We take you for a trip back in time to the foundations of the CTA in 1860 to understand how this history has made it what it is today. You’ll hear from Geneva Tour Guide Catherine Hubert Girod and ICRC Historian Daniel Palmieri recount the history.

The Agencies Through The Ages

The Rath Museum in Geneva, where the International Prisoner of War Agency was established during WWI 1914-1918. (Photo Credit: ICRC Archives)

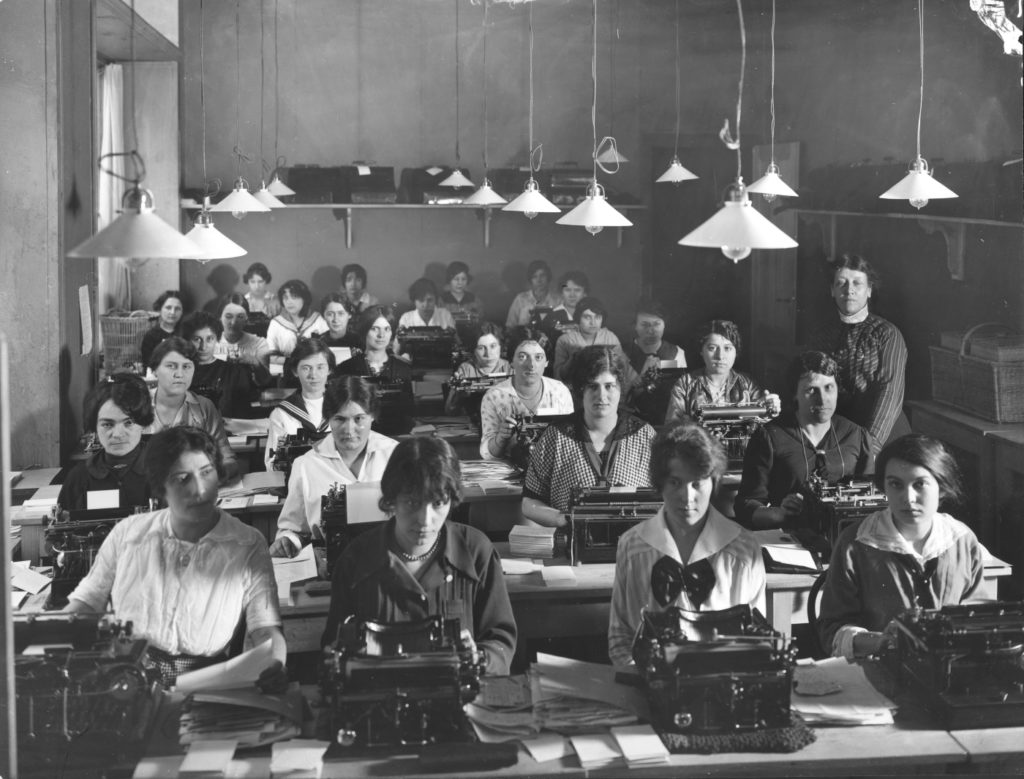

Mostly women worked at the International Prisoners of War Agency while men were off fighting in WWI. (Photo Credit: S.N./ICRC Archives)

As the Central Prisoners of War Agency during WWII, there were more than 40 million index cards to manage. The index cards were categorized by last name. (Photo Credit: ICRC Archives)

In WWII, the ICRC had the authorization to broadcast lists of names of living POWs, displaced persons, or civilian internees, at specific times each day, so that family members could learn the whereabouts of their loved ones. (Photo Credit: S.N./ICRC Archives)

A father searches for a picture of his lost child following the Rwandan Genocide in 1994. (Photo Credit: Benno Neeleman/ICRC Archives)

An unaccompanied child is photographed in hopes that he will be recognized by his family following the Rwandan Genocide. (Photo Credit: Marco Longari/ICRC Archives)

A child is reunited with their family in 2000, six years after the end of the Rwandan conflict. (Photo Credit: Marco Longari/ICRC Archives)

The ICRC’s Tracing Archives

What happens to the files created by the Agency during conflicts, the millions of index cards that document the capture, transfer or death of an individual? The Agency’s files from past conflicts are under the responsibility of a dedicated service of the ICRC. It continues to respond, sometimes decades after the end of a conflict, to requests for information sent by its victims and their descendants. The archival collections under its care also comprise the individual records of beneficiaries, sources of information collected by the Agency such as lists of prisoners and death certificates, and the correspondence, records and administrative archives of the different Agencies.

The exceptional nature of these archives was recognized by UNESCO in 2007, which included the archives of the International Prisoners of War Agency (1914-1923) in its Memory of the World Register. Fully digitized, the Agency’s WWI archives can be viewed online on the ICRC’s Grande Guerre website and are on display at the International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent in Geneva.

Important Links

Read more about the history of the Central Tracing Agency and its legal legitimacy through the centuries. See a timeline of the ICRC’s history of restoring family links.

Read more about the ICRC’s involvement and activities during WWI. Read about the establishment of the International Prisoners of War Agency during WWI.

Read more about the ICRC’s involvement and activities during WWII and the Holocaust. The ICRC archive also offers additional information here.

Watch the documentary about the ICRC’s work during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. Read a reflection on 20 years after the end of the conflict.

Learn more about the agency’s efforts in transmitting love letters between POWs and their loved ones.

Read “A Memory of Solferino“ by the ICRC’s Founding Father Henry Dunant.

This episode is now available for the hearing impaired.

SCRIPT

[Sound of sappy violin music]

[QUOTE FROM HENRY DUNANT’S MEMOIR] “This young man who had joined the army as a volunteer was their only son. The only news they received of him was that which I gave them. Like many others, name appeared among the missing.”

Today we’re taking you back to the past.

As part of our series on the Central Tracing Agency, we’re breaking down how the agency became what it is today–one of the ICRC’s oldest institutions enshrined in the Geneva Conventions and at the heart of the Red Cross Red Crescent humanitarian network.

The agency restores family links for those detained, separated by violence, or lost in a natural disaster. And, it addresses the needs of families of the missing.

I’m Dominique Maria Bonessi and this is Intercross, a podcast that offers a window into the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross and shares the stories of those affected by war and violence.

Just a quick caveat here, we won’t unpack all the geopolitical events that fueled the Agency. This is a taste of what the agency was doing parallel to those events.

If you’d like more information about this history you can go to our website: intercrossblog.icrc.org.

Okay let’s get started.

[Intercross Musical Interlude]

The history of the Central Tracing Agency is as old as the ICRC, itself. To help me tell it, I want to introduce you to Catherine Hubert Girod.

[CATHERINE] “Welcome to Geneva, the birthplace of the Red Cross, and international humanitarian law.”

[Sound of city traffic, horns, buses, and sirens]

Catherine is a tour guide and former ICRC staffer in Geneva, Switzerland, home of the ICRC’s Central Tracing Agency.

She’s going to give us a virtual audio tour of The International Red Cross Red Crescent Museum, also based in Geneva, to help us understand the origins and history of the agency.

[Sound of city fades]

She starts the tour just outside the museum…

[CATHERINE] “I’m at Place de Neuve a very busy Square in the heart of the city. And I’m between two very important monuments and the story. On my left is a bust of a Geneva citizen called Henry Dunant. We are in 1859. And Henry is in northern part of Italy on a business trip. And there he falls upon the carnage 40,000 soldiers had been left to die on the battlefield of Solferino so he stopped his trip. And he tried to help the women of the nearby village of Castiglioni as best as he could, not only to help the physical wounds, but also to address the moral needs of the soldiers.”

[Fade out ambient sound]

Henry Dunant is the founding of father of the ICRC.

[Sound of a sad violin]

In his memoir, “Memory of Solferino” Dunant wrote vividly about the soldiers he met.

[Excerpt being read in French accent] “Don’t let me die!” some of these poor fellows would exclaim—and then, suddenly seizing my hand with extraordinary vigour, they felt their access of strength leave them and died. A young Corporal named Claudius Mazuet, some twenty years old, with gentle expressive features, had a bullet in his left side. There was no hope for him, and of this he was fully aware. When I had helped him to drink, he thanked me, and added with tears in his eyes: ‘Oh, Sir, if you could write to my father and comfort my mother!”

I noted his parents’ address and a moment later he had ceased to live….This young man who had joined the army as a volunteer was their only son. The only news they received of him was that which I gave them. Like many others, name appeared among the missing.”

[Fade violin music]

[City sounds fade back in]

[CATHERINE] “After the soldier passed away, and he returned to Geneva, he then personally hand over the letter to the parents of the soldier. This is the beginning of an activity that is a very important part today of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.”

From the start, the agency’s mandate was limited. It focused on Dunant’s vision of connecting wounded soldiers and their families in war time.

History was set in motion however in 1870, when postal communications were interrupted during the Franco-Prussian War. The ICRC acted as a neutral intermediary between France and Prussia states to exchange information and provide relief for sick and wounded soldiers on both sides.

To do this, the organization created the Basel Agency, named after the northern Swiss border town, where it was located, between the two warring sides.

ICRC Historian Daniel Palmieri explains that it was then the organization saw what worked in theory, didn’t work as well in practice. Changes needed to be made.

[DANIEL] “He realized that by helping only wounded or sick soldiers, it was creating an unfair situation in relation to able bodied soldiers who were not protected or who were not assisted the Basel Agency. And especially tens of thousands of these able-bodied soldiers were prisoners, French prisoners in Germany, who also needed help. So, it started also to work for prisoners of war, not only for wounded or ill soldiers.”

At the reception area, a doctor caring for soldiers in Basel found that most of them were in a state of distress because their families had no idea whether they had been killed or taken prisoner.

[DANIEL] “The ICRC realized but in addition to material needs, such as the need to receive assistance or relief, there was also what he called a moral suffering. The Basel agency started to be a kind of mailbox between families and prisoners of war. And directly linked to with this operation, the Basel agency and the ICRC became also involved in tracing missing prisoners of war, and in publishing lists of sick and wounded prisoners, especially the French one.”

The Basel Agency therefore went one step further, transmitting lists of prisoners: for the first time in history, the relatives of captured soldiers heard that their sons, fathers, brothers were alive but in enemy hands.

The ICRC re-opened a new agency for each of the major conflicts in the first half of the 20th century. It established an index card system, registering by hand tens of thousands of POWs.

This operational experience proved invaluable in the lead up to the first and second World Wars.

[DANIEL] “And when the information was received, the ICRC made research for its very huge index card system. We had 87,000 information about prisoners during the two Balkans wars. But during the First World War, we had 7 million of information about prisoners of war. So we, ICRC, had a lot of business to do to find information. And after when the information was found, the letter continued to the prisoners of war or to a family. And it could take two three months, again, because versus sort of the censorship. And it depends if a prisoner were in Europe, it could take between one or two months. But if the captive were outside Europe, and for instance, you are the German or Austrian prisoners of war in Japan, so it could take easily seven or eight months by boat.”

The core of their mandate would always remain similar for the different agencies: offering protection and relief to POWs, which included exchanging correspondence between family members and POWs.

Like this one written much later during World War II by a French prisoner of war to his wife in Casablanca.

[Male voice reads from a letter with an old-timey filter] “November 1942… Destiny keeps separating us. Here I am unable to help you. Everyday my thoughts bring me closer to you.”

Or this letter written by a spouse to a French prisoner, who was in German custody.

[Female voice reads from a letter with an old-timey filter] “January 1943… We have been separated three years now, but soon, I hope, I will be in your arms.”

But again, as crucial as the transfer of correspondence was – the Basel Agency and other tracing agencies set up by the ICRC had no real legal legitimacy to carry out this work.

[Sounds of walking in an empty hallway]

Now walking through the corridors of the International Red Cross Red Crescent Museum in Switzerland — Catherine demonstrates what a massive undertaking this evolved into being. But it wasn’t just a de facto mail service.

[CATHERINE] “Whether it is due to an armed conflict or a natural catastrophe, people suffer greatly, and especially when they have no news of their families. This is why there is a whole section of the museum dedicated to tracing missing people and reestablishing contact. I will now enter this section through a number of chains in order to reach the actual core of this area. And here I have passed the chains and I’m surrounded by boxes and boxes and boxes of index cards, 6 million index cards, registering prisoners of war from the First World War”

At the outbreak of hostilities, members of the ICRC took charge of setting up the new international prisoners of war agency – but they had no idea how widespread the war was going to become.

With the help of the network of Red Cross/Red Crescent Societies, it would collect lists of captured soldiers’ names and forward the information on their hometowns. Catherine brings us back to those index cards and explains what it was like to work at the agency when it was headquartered at the Rath Museum in Geneva.

[CATHERINE] “So you are a volunteer at the International prisoner of war agency in Geneva, you’re at the Museum, and it is summer of 1917. You have received a letter from a family in Germany, looking for a soldier called August Binders. on an index card, you will write down all the information that’s in this letter, the surname and the first name of the soldier being sought. Together with his date of birth and his regimental details, as well as the date and place where he went missing this case it was 16th of April 1917. You will then take this index card and put it in a box in alphabetical order by surname. Now a few days later, you receive a list of German prisoners of war is captured. And you will also start making another index card with information on the different soldiers. Again, his regimental number, his surname, his first name, his rank and date of place of birth. And you will put this on this second index card which you will also put in alphabetical order by surname. And you will have just written one for a certain August bias. And so there will be a match with the first index cards you wrote with information from the family. You have now located the prisoner of war, and you will be able to write to the family to inform them and on that index card with family information. You will put down everything that is done regarding this prisoner of war, exchange of messages, exchange of parcels if he was sick, and all of this was done, handwritten and typed by a typing machine. Really, you can say that this was a logistical challenge in view of the technological knowledge that we had at that time.”

During this time the agency also began its field work, visiting detained prisoners of war, which allowed delegates to be closer to the needs of those detained, and in direct contact with their suffering.

[CATHERINE] “The purpose is to assess the humanitarian conditions of these detainees and also to register them. Now, sometimes the only persons from the outside that these prisoners get to meet and talk with our ICRC delegates. And that’s why I’m in a room now surrounded by objects, objects made by the prisoners in captivity and given as presents to ICRC delegates. Some of them are absolutely exquisite, such as this one here in front of me. It is a little T set made by Russian prisoners of war during the First World War. It is very delicate and made from fish bones.”

[Music plays underneath]

By the end of the war, more than 6 million files had been opened by the Agency. It had also sent family packages to prisoners of war and civilians in occupied territories, and organized the repatriation of victims.

A gigantic humanitarian endeavor had been accomplished, and the ICRC had found a lasting model in the International Prisoners of War Agency in the first World War.

The Geneva Convention of 1929 marked a major shift in international law when—for the first time–prisoners of war were protected in international armed conflict.

The Central Agency of Information is also finally mentioned by name, which augmented ICRC’s legitimacy in providing this humanitarian work.

[DANIEL] “There were a lot of similarity in the way of working because the ICRC had to adapt what was learned from the First World War with this new context of War, Second World War.”

One of the organization’s first steps after hostilities broke out in 1939 was to establish the Central Prisoners of War Agency, a clearing house for information on prisoners.

Instead of roughly 7 million index cards of registered POWs, there were now tens of millions of index cards to manage; the agency would also receive tens of millions of letters.

Faced with an unprecedented situation, the ICRC gave the Central Prisoners of War Agency the most modern means of communication available at the time: photocopiers, calculators for statistics–and radio.

ICRC had the authorization to broadcast lists of names of living POWs, displaced persons, or civilian internees, at specific times each day, so that family members could learn the whereabouts of their loved ones. It was proof of life.

[POW names being read off by radio host from 1950s]

This was also the case much later, during the Korean War in 1954.

On other occasions, POWs could read off messages to their families themselves.

[The song of “Jingle Bells” plays underneath.]

U.S. Army Sergeant First Class Stanley Bartholomew Jr. was a prisoner of war in China.

[STANLEY.] “My dearest wife and children, once again through the courtesy of the Chinese people and committee for world peace. I am able to broadcast a letter to you and for you and the children to hear my voice so many miles from home. Darling with Christmas approaching again I hope you can see fit to have a decent one for the children even though I may not be able to be there with you. So Merry Christmas to you all and God bless you. All the love, Stanley.”

[“Jingle Bells” fades]

But there was something else revolutionary that arrived to the ICRC in World War II—the IBM computer.

[DANIEL] “I think for me, one of the most important innovation for this work was what we call at the agency Watson service and this system used perforate cards and worked according to an electromagnetic process. And ICRC used the machine to produce lists of prisoners of war in alphabetical or numeric order. And this machine where machines were able to deal with several 1000 names an hour so it was a great time and energy saver to do individual research.”

Over six years, the Agency filled in around 25 million of these individual identity cards for POWs and passed on some 120 million messages between prisoners of war and their families. It also distributed 36 million Red Cross parcels.

The new 1929 Geneva Convention proved effective in protecting captured combatants, but tragically not all of them.

[PAUSE, high-pitched drone sound plays underneath]

Not only had the Soviet Union not signed onto the treaty, but both Germany and the Soviet Union refused to sign an agreement on the exchange of information on POWS between the two.

Additionally, parties to the treaty refused to extend benefits of the 1929 Convention to protect civilians in occupied territories. That meant civilians in Nazi concentration camps were deprived of any protection at all under international law, during this brutally tragic time in history. And just registering names was a challenge:

[DANIEL] “The ICRC had the opportunities to send parcels, to sometime obtain names via acknowledgement of receipt of his parcels. And generally, one acknowledgement or receipt, you could have one name, but other inmates could also sign give their name, and so the ICRC was able to dispatch a lot of, more parcels to the camps. But the ICRC was not allowed. Some exception exists but generally was not allowed to enter to the concentration camps.”

[Drone sound fades]

[PAUSE]

[DANIEL] “And after the official termination of World War Two, in fact, the central agency for prisoners of war continued its work as an intermediary between the prisoners of war who are not being freed or repatriated, and especially all the prisoner from Germany or Japan or Italy and their family, and it continued also to deal with tracing inquiries on missing persons or on misplaced populations, as a consequence of World War Two.”

[Sound of someone speaking in French at 1949 Geneva Conventions]

In the dark shadow of World War II, states’ representatives ratified the Geneva Conventions of 1949, codifying into law that civilians are to be protected from murder, torture, or brutality, and from discrimination on the basis of race, nationality, religion or political opinion.

[DANIEL] “So for the ICRC the war didn’t end with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The work of the ICRC is very starting. In fact due to the huge consequences of Second World War, it never finished its work, and it became a permanent department of the ICRC.”

On July 1st, 1960 the agency was rebranded to simply the Central Tracing Agency, notably without “Prisoners of War” from its title for the first time.

That’s because the Agency began reuniting families and tracing all persons held captive and others reported as missing, not just from International Armed Conflicts–but non-international armed conflicts as well.

In modern times, the Agency still works on behalf of detainees. But it has scaled up its activities for civilians while responding to the humanitarian consequences of armed conflicts, violence, disasters and migration. This all happens with the help of Red Cross Red Crescent Societies on the ground.

Back at the Red Cross Red Crescent Museum, Catherine takes us to the last part of the exhibit. It features hundreds of photos of young children who at the time they were taken, were looking for their families following the 1994 Rwandan Genocide.

They’re small photos, stacked one after the other, all with a white background. Seeing them together, you get a sense of just how many there are.

[CATHERINE] “Now what happens when we’re trying to find the relatives of children, especially when they’re very young, they don’t know their parents full name or the name of the village or the city where they came from. And this is what happened in wonder after the genocide in 1994. So here, the ICRC together with UNICEF, started taking pictures and documenting each child and then put this in an album that was sent to the different refugee camps around Rwanda.”

It was an enormous task, which involved listening to each child’s story to understand their particular situation.

Six years after the end of the Rwandan conflict, and despite the more than 74-thousand unaccompanied children that were registered by the ICRC and the Red Cross National Society on the ground, roughly 67-thousand were reunited with family members. It was a lasting testimony to both the success of this extensive operation, but also the unbearable trauma of families.

So through the centuries, the Agency has undergone a series of evolutions, during multiple armed conflicts.

For much of it, the experience came first, spurred on by moral and technological innovations, then codified in international law, making the Agency what it is today.

[DANIEL] “The CTA and its predecessors have been the spine around the ICRC built itself during decades to become the humanitarian organization we know today.”

[Music plays]

Thank yous today go to Catherine Hubert Girod for the tour and ICRC Historian Daniel Palmieri for your research.

If you want to learn more about the ICRC and its work with Red Cross Red Crescent societies around the world, I encourage you to pay a visit to the museum.

And, if you’re searching for family records of current or past POWs, please email the Central Tracing Agency’s archive directly at archive@icrc.org.

Finally, if you liked this episode or you have other questions about the Central Tracing Agency we want to hear from you.

You can respond on Twitter to our handle @ICRC_DC or contact us through our website, that’s intercrossblog.icrc.org. While you’re there you can see all of our most recent episodes and subscribe to our newsletter so you never miss a podcast.